ViDoRe V3: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation in Complex Real-World Scenarios

Abstract

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) pipelines must address challenges beyond simple single-document retrieval, such as interpreting visual elements (tables, charts, images), synthesizing information across documents, and providing accurate source grounding. Existing benchmarks fail to capture this complexity, often focusing on textual data, single-document comprehension, or evaluating retrieval and generation in isolation. We introduce ViDoRe V3, a comprehensive multimodal RAG benchmark featuring multi-type queries over visually rich document corpora. It covers 10 datasets across diverse professional domains, comprising 26,000 document pages paired with 3,099 human-verified queries, each available in 6 languages. Through 12,000 hours of human annotation effort, we provide high-quality annotations for retrieval relevance, bounding box localization, and verified reference answers. Our evaluation of state-of-the-art RAG pipelines reveals that visual retrievers outperform textual ones, late-interaction models and textual reranking substantially improve performance, and hybrid or purely visual contexts enhance answer generation quality. However, current models still struggle with non-textual elements, open-ended queries, and fine-grained visual grounding. To encourage progress in addressing these challenges, the benchmark is released under a commercially permissive license111https://hf.co/vidore.

ViDoRe V3: A Comprehensive Evaluation of Retrieval Augmented Generation in Complex Real-World Scenarios

António Loison††thanks: Equal contribution††thanks: Work done while at Illuin Technology Quentin Macé∗1,3 Antoine Edy∗1 Victor Xing1 Tom Balough2 Gabriel Moreira2 Bo Liu2 Manuel Faysse3† Céline Hudelot3 Gautier Viaud1 1Illuin Technology 2NVIDIA 3CentraleSupélec, Paris-Saclay {antonio.loison, quentin.mace, antoine.edy}@illuin.tech

1 Introduction

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) (Lewis et al., 2021) has become the dominant paradigm for knowledge-intensive NLP tasks (Gao et al., 2024; Fan et al., 2024). Yet practical deployments introduce complexities that academic benchmarks often overlook when focusing on single-document textual retrieval. First, documents encode critical information in visual elements such as tables, charts, and images designed for human interpretation, which text-only pipelines often ignore (Abootorabi et al., 2025; Cho et al., 2024b). Second, user queries often require open-ended synthesis, comparison, and reasoning over scattered information, not simple factoid lookup (Tang and Yang, 2024; Thakur et al., 2025; Conti et al., 2025). Third, trustworthy systems must ground responses to specific source locations (e.g., bounding boxes), to mitigate hallucinations (Gao et al., 2023; Ma et al., 2024b).

Existing benchmarks leave these requirements only partially addressed. Early Visual Document Understanding (VDU) benchmarks focus on single-page comprehension, ignoring the complexity of large document corpora (Mathew et al., 2021b). Recent retrieval-centric benchmarks do not evaluate generation quality and grounding (Faysse et al., 2025; günther2025jinaembeddingsv4universalembeddingsmultimodal). Some multimodal datasets attempt to bridge this gap but rely on extractive, short-answer tasks that fail to exercise complex reasoning (Cho et al., 2024a), or lack multilingual diversity and fine-grained visual grounding (Peng et al., 2025).

To address these limitations, we introduce ViDoRe V3, a benchmark designed for complex and realistic end-to-end RAG evaluation on visually rich document corpora. Our contributions are:

1. A Human Annotation Methodology for Realistic Queries

We propose an annotation protocol for generating diverse queries and fine-grained query-page annotations. By restricting annotator access to document content during query formulation, we capture authentic search behaviors and mitigate bias toward simple extractive queries. Vision-Language Model (VLM) filtering combined with human expert verification enables efficient, high-quality annotation at scale.

2. The ViDoRe V3 Benchmark

Applying this methodology to 10 industry-relevant document corpora, we build ViDoRe V3, a multilingual RAG benchmark comprising 26,000 pages and 3,099 queries, each available in 6 languages. Two datasets are held out as a private test set to mitigate overfitting. The benchmark is fully integrated into the MTEB ecosystem and leaderboard222https://mteb-leaderboard.hf.space (Muennighoff et al., 2023), and the public datasets are released under a commercially permissive license.

3. Comprehensive Evaluation and Insights

Leveraging our granular annotations, we benchmark state-of-the-art models on (i) retrieval accuracy by modality and language, (ii) answer quality across diverse retrieval pipeline configurations, and (iii) visual grounding fidelity. Our analysis surfaces actionable findings for RAG practitioners.

2 Related Work

Component-Level Benchmarks (VDU and Retrieval)

VDU has traditionally relied on single-page datasets like DocVQA (Mathew et al., 2021b), alongside domain-specialized variants (Mathew et al., 2021a; Zhu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2024). These ignore the multi-page context inherent to RAG. Recent work evaluating bounding-box source grounding (Yu et al., 2025b) proposes single-page and multi-page tasks but does not address the retrieval component. Conversely, the emergence of late-interaction visual retrievers (Ma et al., 2024a; Faysse et al., 2025; Yu et al., 2025a; Xu et al., 2025) spurred the creation of retrieval-centric visual benchmarks like Jina-VDR (günther2025jinaembeddingsv4universalembeddingsmultimodal) and ViDoRe V1&V2 (Faysse et al., 2025; macé2025vidorebenchmarkv2raising), but none of these benchmarks jointly evaluate retrieval and answer generation.

End-to-End Multimodal RAG

While recent textual RAG benchmarks now capture complex user needs like reasoning or summarizing (Thakur et al., 2025; Tang and Yang, 2024; Su et al., 2024), multimodal evaluation often remains limited to single page queries (Faysse et al., 2025). Multi-page datasets like DUDE (Van Landeghem et al., 2023), M3DocRAG (Cho et al., 2024b), ViDoSeek (Wang et al., 2025) or Real-MM-RAG (Wasserman et al., 2025) prioritize extractive retrieval, lacking the diversity of queries encountered in realistic settings. UniDocBench (Peng et al., 2025) represents a concurrent effort that similarly addresses diverse query types and provides comparative evaluation across multiple RAG paradigms. While this benchmark offers valuable contributions, it relies on synthetically generated queries via knowledge-graph traversal, is restricted to English documents, and constrains grounding annotations to parsed document elements. In contrast, our benchmark offers several complementary strengths: fully human-verified annotations, multilingual coverage, free-form bounding box annotations, and a more systematic evaluation of individual visual RAG pipeline components.

3 Benchmark Creation

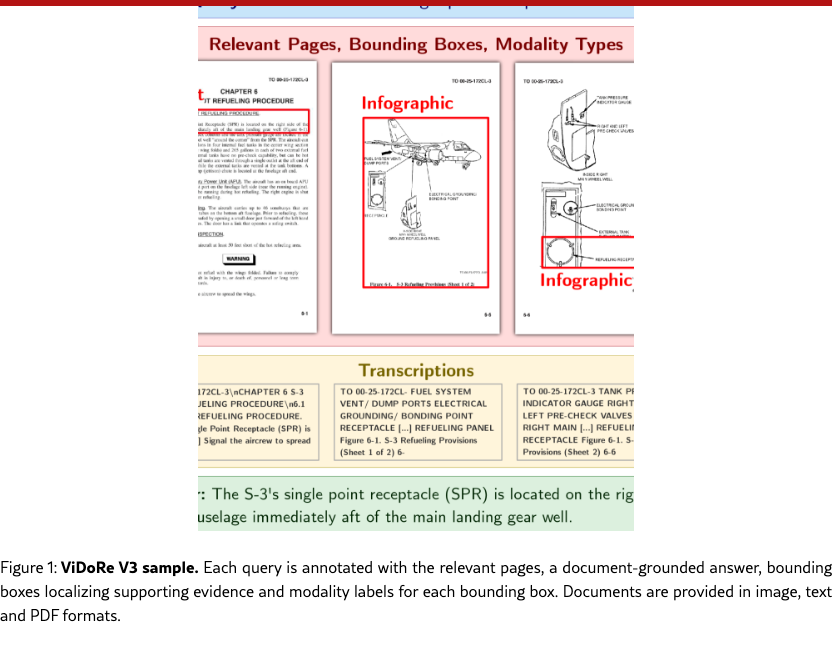

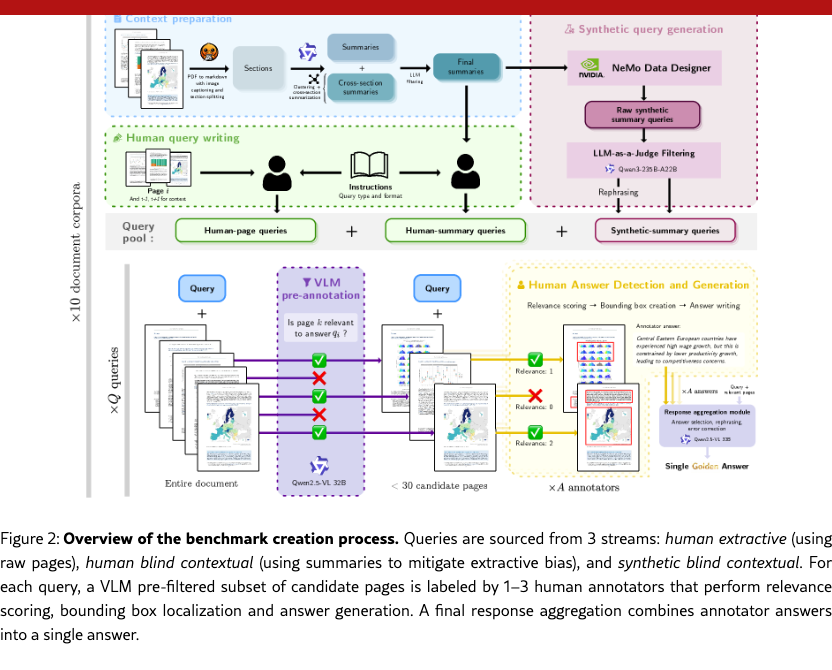

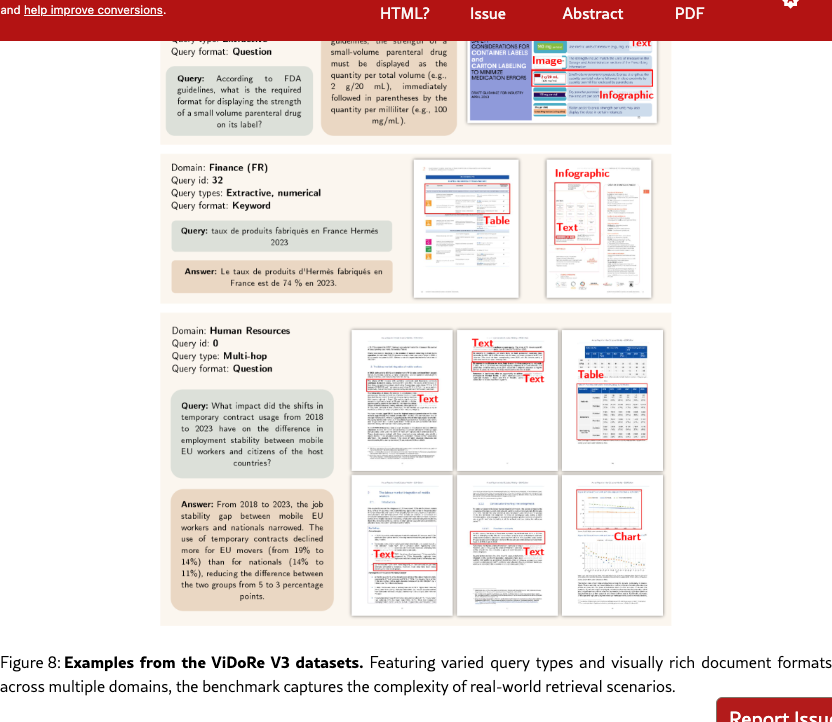

We design the benchmark to mirror the diversity of information retrieval situations in large-scale realistic environments. To enable pipeline-agnostic evaluation of the 3 core RAG components (retrieval, generation and grounding), while avoiding limitations of synthetic benchmarks, we employ a rigorous three-stage human-in-the-loop annotation process involving document collection, query generation and grounded query answering (Figure˜2).

3.1 Document Collection

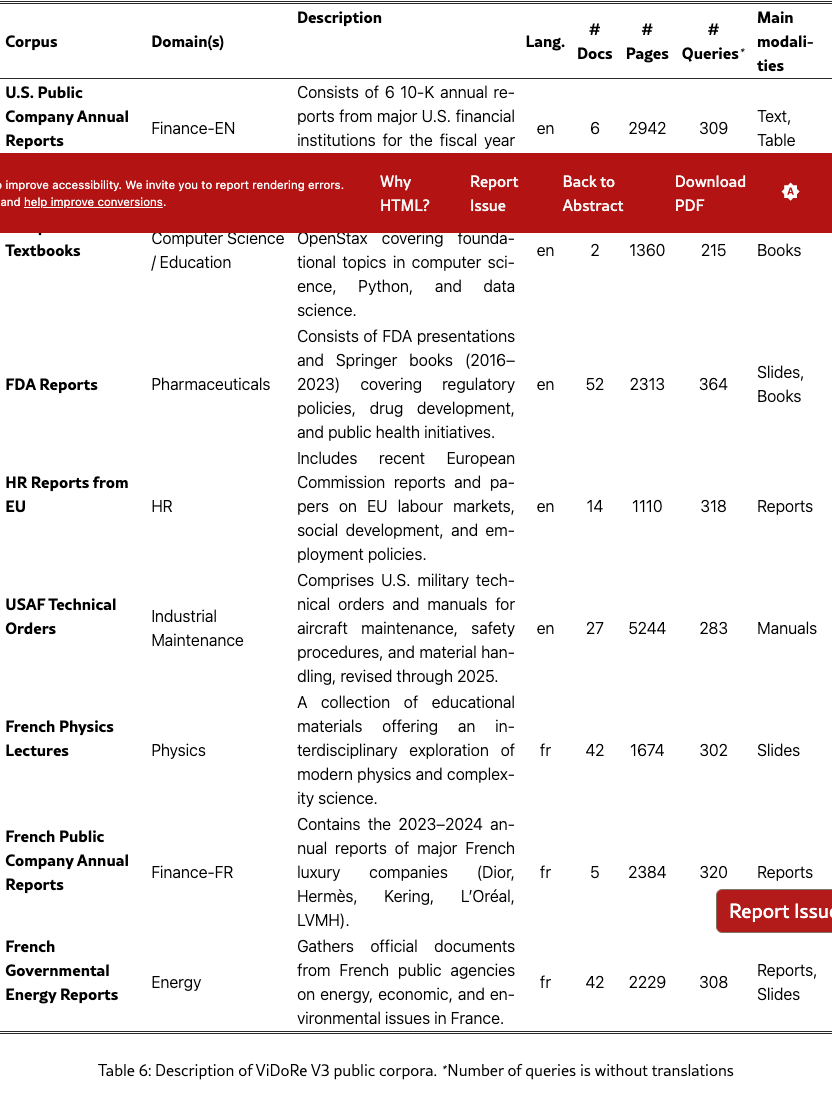

We curate 10 diverse corpora by manually selecting openly-licensed documents from governmental, educational, and industry sources, focusing on English and French documents (7 and 3 corpora respectively). The corpora span Finance, Computer Science, Energy, Pharmaceuticals, Human Resources, Industrial Maintenance, Telecom, and Physics. Each features domain-specific terminology and document structures representative of realistic retrieval tasks (details in Table˜6).

3.2 Query Generation

Query Taxonomy

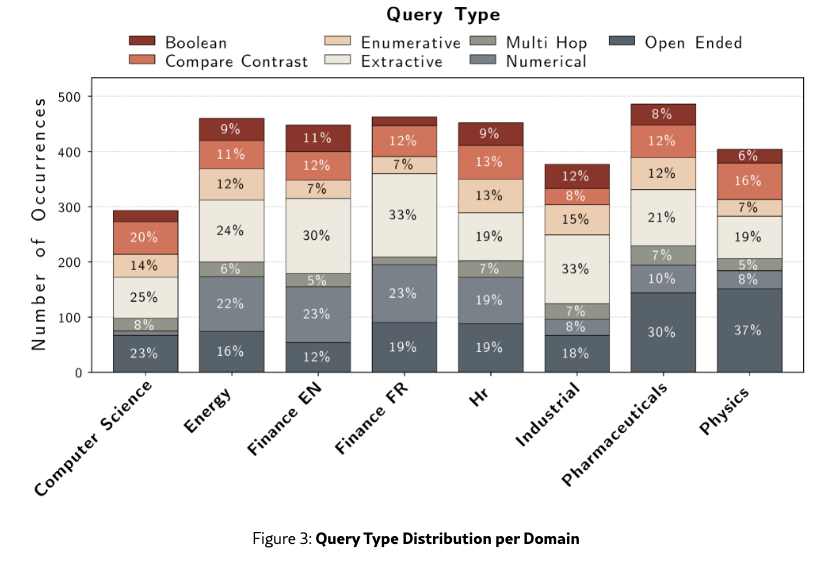

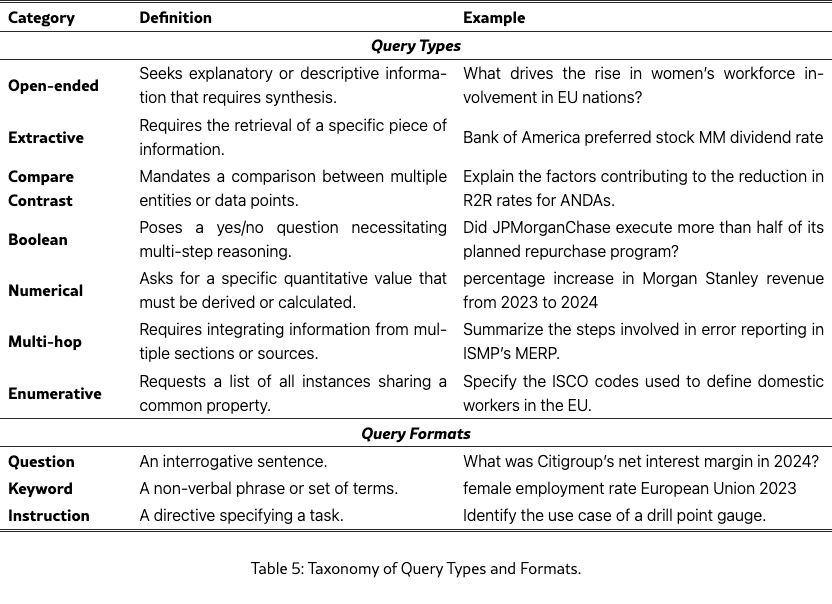

To evaluate document visual retrieval systems across diverse realistic scenarios, we develop a query taxonomy with two orthogonal dimensions: Query Type, defining the user’s information need, and Query Format, describing the query’s syntactic structure. This dual-axis classification enables more nuanced performance analysis than benchmarks focusing solely on interrogative extractive queries. We define 7 Query Types: open-ended, extractive, numerical, multi-hop, compare-contrast, boolean, and enumerative, and 3 Query Formats: question, keyword, and instruction.

Context Preparation

We further ensure query diversity by pulling summaries from a heterogeneous set of contexts during the generation process.

Two types of input contexts are used: specific document sections that target local information retrieval and cross-section summaries that target multi-document context retrieval. These summaries are produced through a refined process inspired by ViDoRe V2 macé2025vidorebenchmarkv2raising. First, the text is extracted from PDFs using Docling Auer et al. (2024) along with image descriptions. Then, summaries are generated with Qwen3-235B-Instruct Qwen Team (2025) from each document section. They are clustered to group similar summaries together using Qwen3-Embedding-0.6B Zhang et al. (2025) as embedder, UMAP McInnes et al. (2020) for dimension reduction and HDBSCAN Campello et al. (2013) for clustering. Additionally, cross-section summaries are produced by synthesizing the summaries of 2 to 3 randomly selected sections per cluster. From this pool of summaries, a final subset is curated to maintain a strict balance between single-section and cross-section summaries. The selection also ensures an even distribution across section modalities (text, images, and tables) as defined by the Docling element classification.

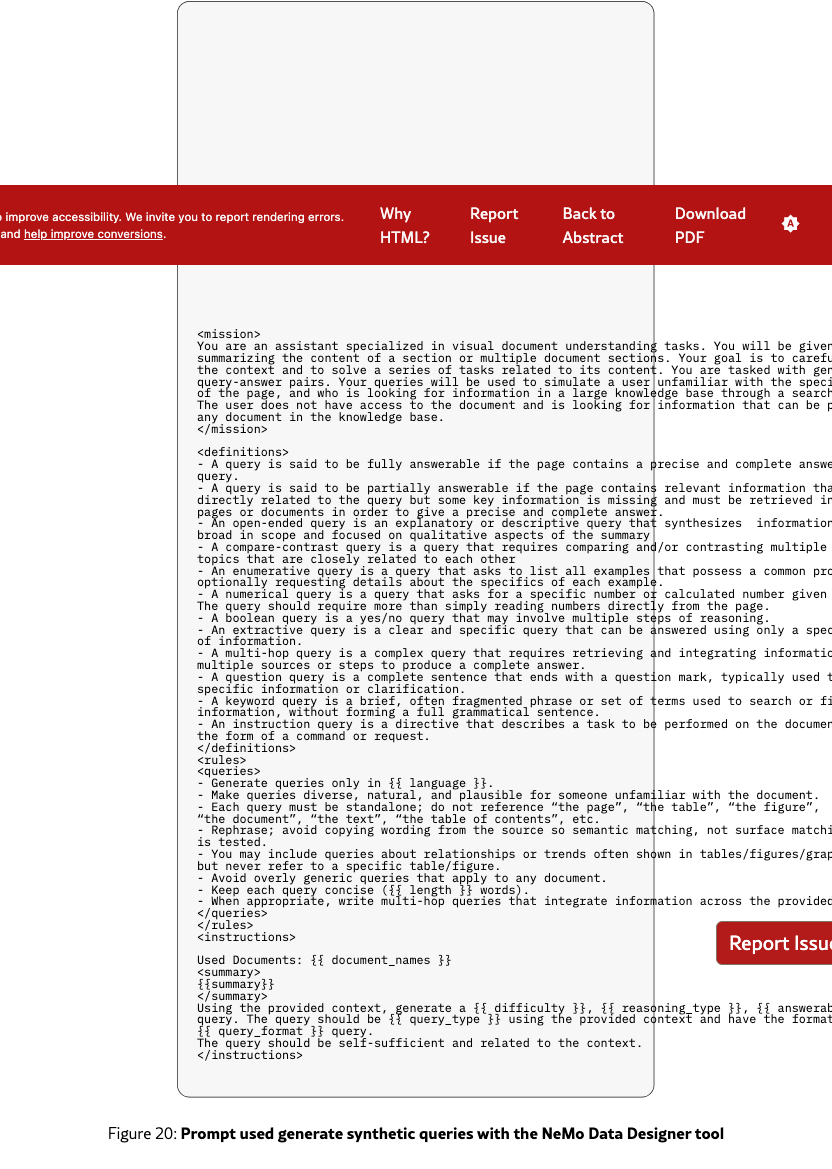

Synthetic Query Generation

Queries are generated from the summaries using a first synthetic generation pipeline based on Qwen3-235B. For each summary, a prompt is constructed by sampling a query type and format at random, together with variable attributes such as length and difficulty, in order to promote diversity. The generated queries are subsequently evaluated by the same LLM acting as an automatic judge, which filters outputs according to 4 criteria: information richness, domain relevance, clarity and adherence to query type/format. Finally, 50% of the retained queries are rephrased to further enhance linguistic variance. This pipeline is implemented using NeMo Data Designer NeMo Data Designer Team (2025) to facilitate generation scaling.

Human Query Writing

Human annotators are provided 2 kinds of contexts: synthetic summaries or specific PDF pages. They are tasked with generating one query following a specific query type and format and one query of their choice that is most adapted to the context provided.

3.3 Answer Detection and Generation

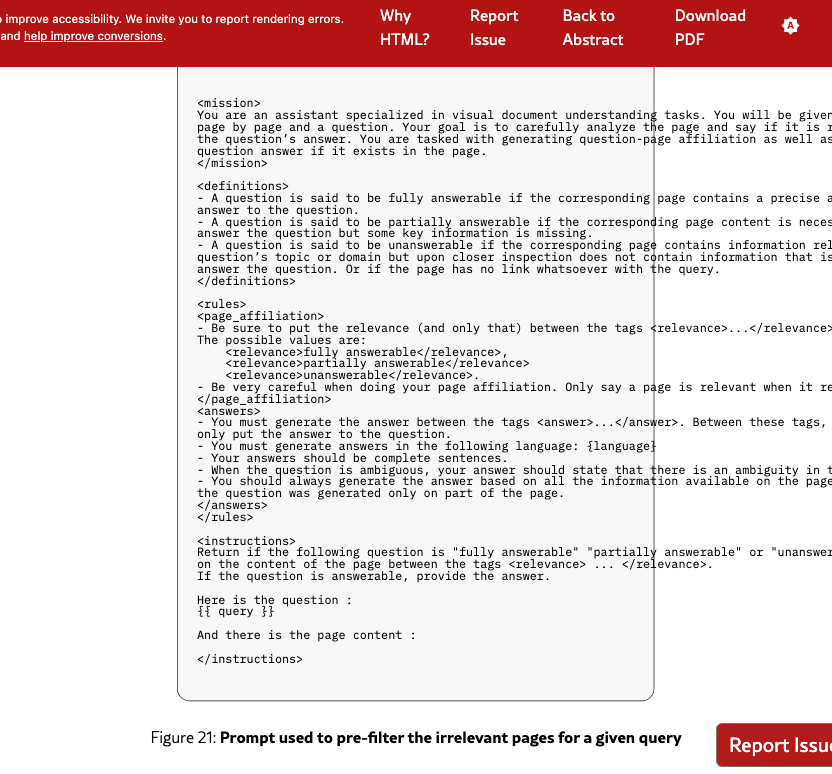

Queries are filtered and linked to relevant pages using a hybrid pipeline of VLM pre-filtering and human annotation. It is followed by human answer annotation and visual grounding.

Query-Page Linking

Given the scale of our corpora, manual verification of each page relevance for each query is intractable. We therefore adopt a two-stage annotation pipeline. First, Qwen2.5-VL-32B-Instruct (Bai et al., 2025) pre-filters candidate pages by assessing whether each page image is relevant to the query. Queries whose answers span more than 30 flagged pages are discarded. Human annotators then review the remaining query-page pairs, evaluating query quality and rating page relevance on a three-point scale (Not Relevant, Critically Relevant, Fully Relevant).

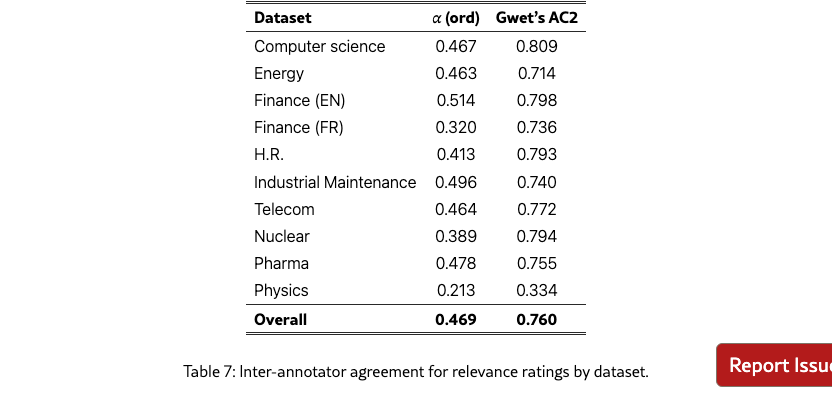

Relevant Page Selection

To ensure annotation quality, each task is completed by multiple annotators and reviewed by annotation supervisors. Since VLM pre-filtering biases the distribution toward relevant pages, we report Gwet’s AC2, as it remains stable under prevalence skew, at 0.760 (see Appendix˜D for dataset-level breakdowns). Given this strong but imperfect agreement, we implement a tiered review process: extractive queries require at least one annotator and one reviewer, while more complex non-extractive queries require at least two annotators and one reviewer. A page is retained as relevant if marked by either (i) one annotator and one reviewer, or (ii) at least two annotators.

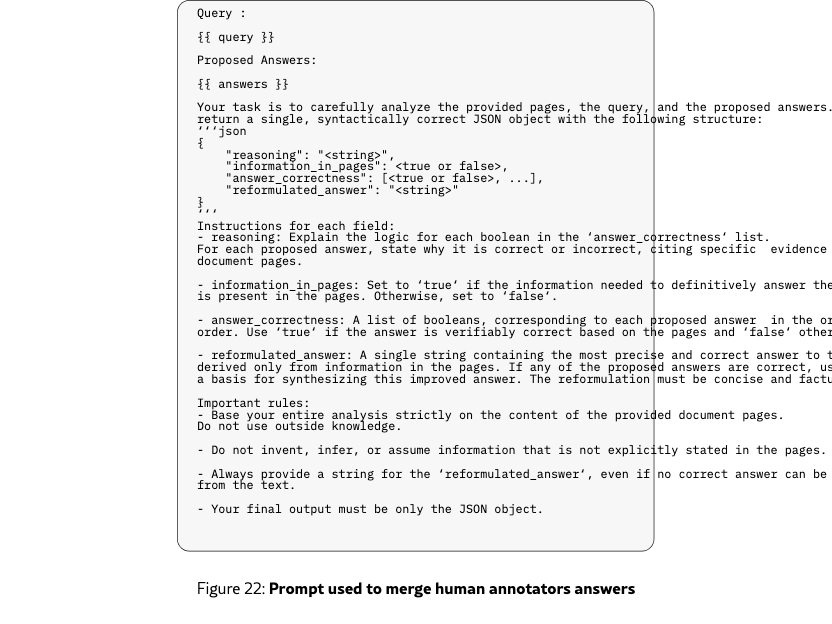

Answer Generation

For each selected query, annotators were tasked with writing an answer based on the pages they marked as relevant. Given that different annotators might have different answer interpretations and tend not to be exhaustive in their answers, we use Qwen2.5-VL-32B-Instruct to generate a final answer based on the relevant page images marked by the annotators and their answers.

Bounding Boxes and Modality Types

For each relevant page, annotators delineate bounding boxes around content supporting the query and attribute a modality type to each bounding box: Text, Table, Chart, Infographic, Image, Mixed or Other.

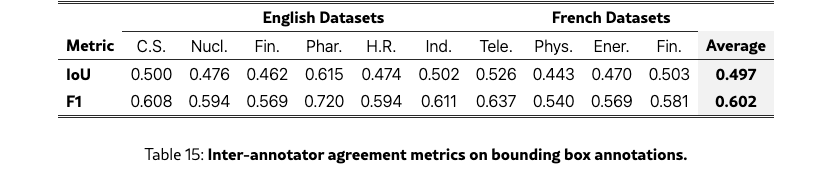

Because multiple valid interpretations of bounding boxes can exist, we perform a consistency study to evaluate inter-annotator agreement and establish a human performance upper bound for the task.

We compute inter-annotator agreement on the subset of query-page pairs labeled by two or three annotators. For each annotator, we merge all their bounding boxes into a single zone. We then compare zones across annotators by measuring pixel-level overlap, reporting Intersection over Union (IoU) and F1 score (Dice coefficient). When three annotators label the same sample, we average over all pairwise comparisons.

Across all 10 datasets, we observe an average IoU of 0.50 and F1 of 0.60. These moderate agreement scores reflect the inherent subjectivity of the task: annotators typically agreed on the relevant content but differed in granularity (Appendix 17), with some marking tight bounds around specific content while others included surrounding context.

Quality Control

The annotation was conducted by a curated pool of 76 domain-qualified experts with native-level language proficiency. Quality control was performed by 13 senior annotators with enhanced domain knowledge and extensive annotation experience. Detailed protocols regarding the annotator pool and training are provided in Appendix C.

3.4 Final Query Distribution

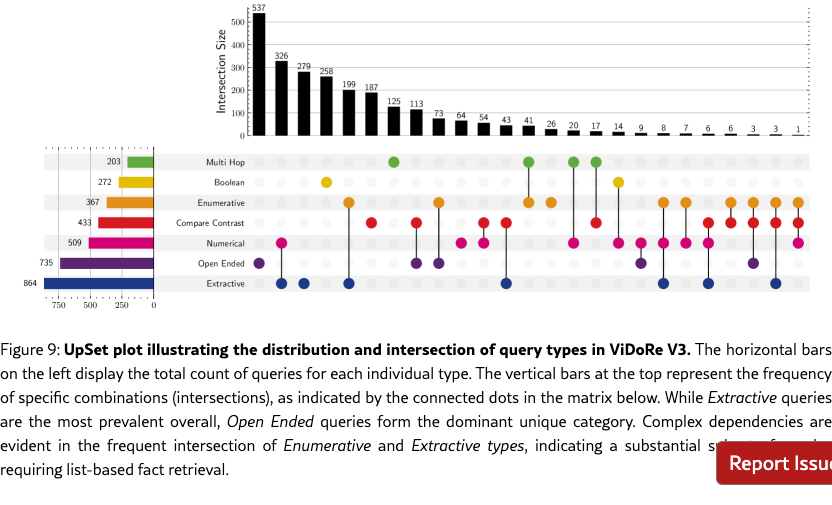

We conducted a final human review to remove low-quality queries and resolve labeling ambiguities. Figure˜3 shows the resulting distribution. Extractive queries predominate due to human annotator preference, followed by open-ended queries from targeted sampling. Multi-hop queries were the hardest to scale, suggesting a need for dedicated pipelines. Figure˜4 details page modalities; while text is most prevalent, visual elements like tables, charts, and infographics are well-represented.

3.5 Dataset Release and Distribution

We extend the benchmark to rigorously assess cross-lingual retrieval. While source documents are maintained in English and French, we use Qwen3-235B-Instruct to provide translations in 6 languages: English, French, Spanish, German, Italian, and Portuguese. This configuration challenges models to bridge the semantic gap between the query language and the document language, a critical requirement for modern RAG systems.

Finally, to ensure the integrity of evaluation and mitigate data contamination (which was shown to be a major preoccupation for Information Retrieval Liu et al. (2025)), we adopt a split-release strategy. 8 datasets are made public to facilitate research, while 2 are retained as private hold-out sets. This enables blind evaluation, ensuring that performance metrics reflect true generalization rather than overfitting to public samples.

4 Experiments and Results

Using our benchmark, we conduct extensive evaluations across all 3 components of RAG pipelines. We assess textual and visual retrievers and rerankers on retrieval performance, evaluate leading VLMs and LLMs on their ability to generate accurate answers from various retrieved contexts, and test VLMs on bounding box generation for visual grounding. From these results, we compile practical insights for RAG practitioners.

4.1 Retrieval

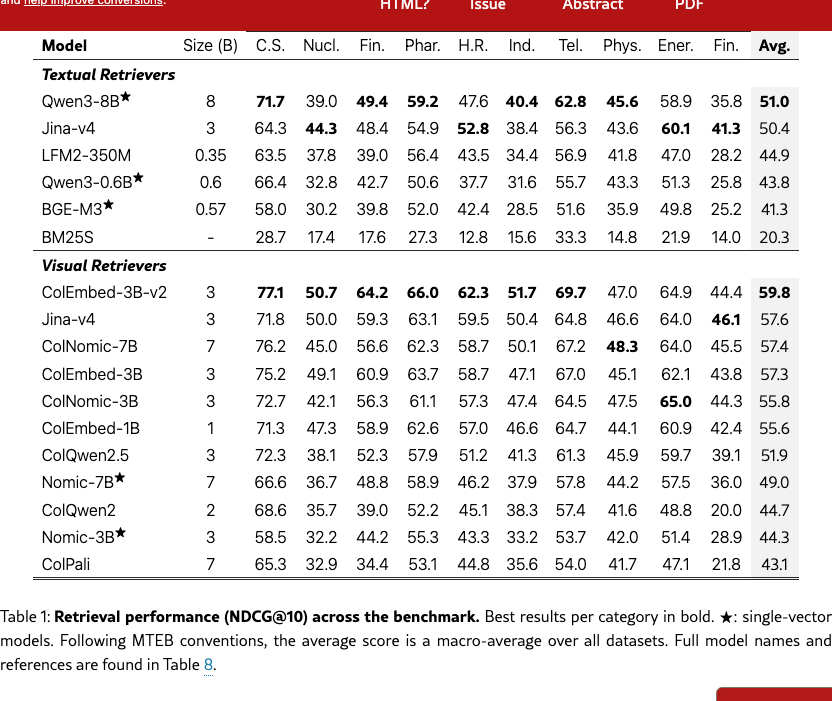

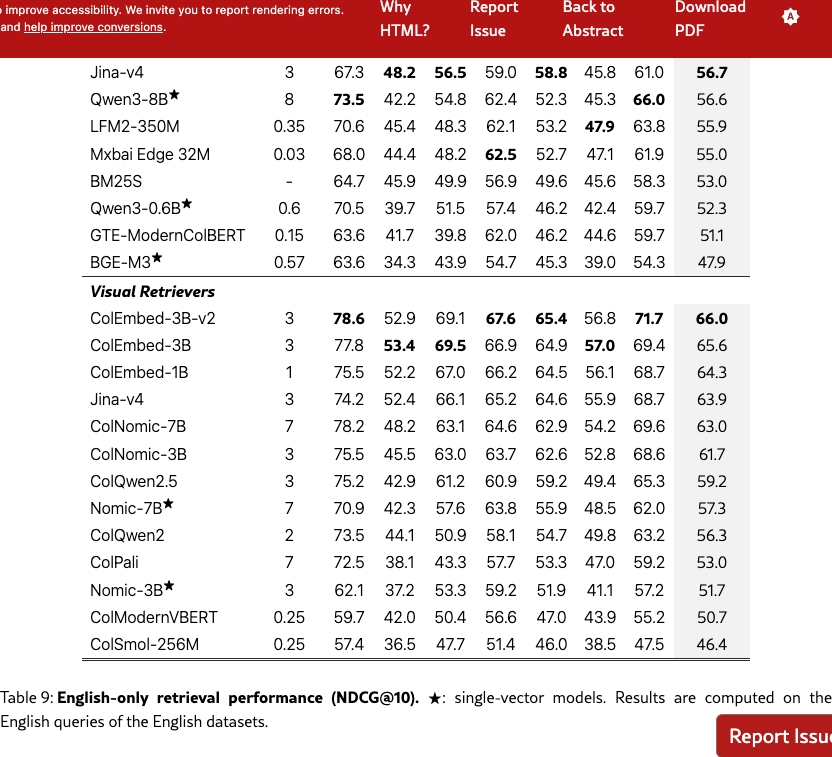

We evaluate a large panel of visual and textual retrievers on page-level retrieval ability. Visual retrievers are given page images, while textual retrievers process the Markdown text of each page processed by the NeMo Retriever extraction service333Chunking within pages or providing image descriptions did not improve our results. Thus, we report the results of the simplest pipeline. NVIDIA Ingest Development Team (2024). The results reported in Table 1 corroborate findings from existing document retrieval benchmarks Faysse et al. (2025); günther2025jinaembeddingsv4universalembeddingsmultimodal: for a given parameter count, visual retrievers outperform textual retrievers, and late interaction methods score higher than dense methods.

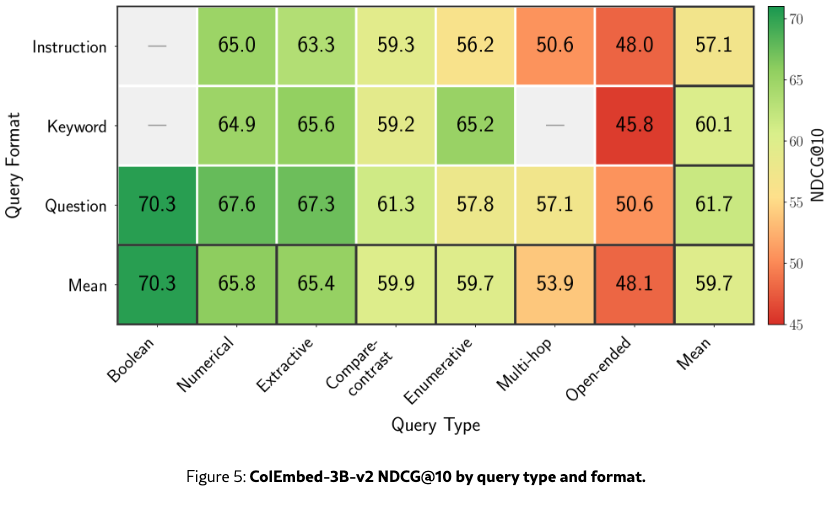

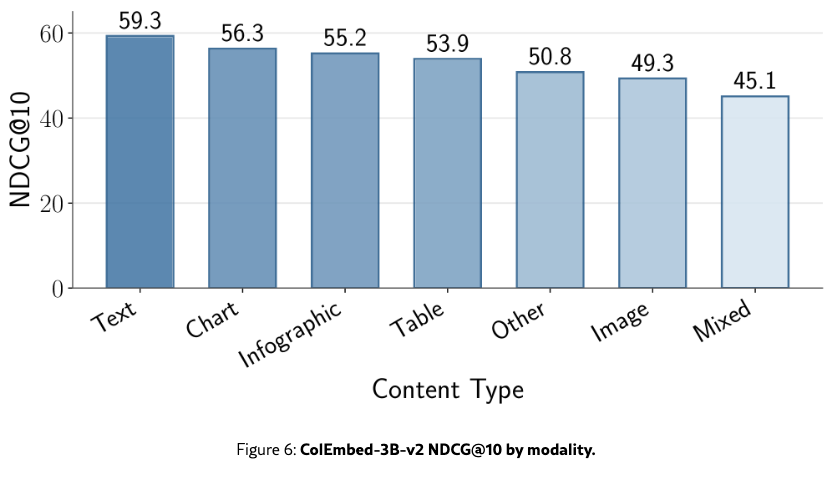

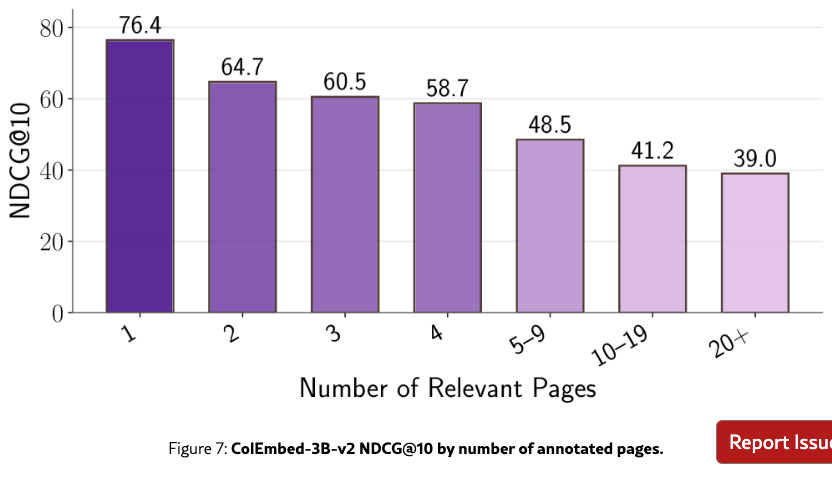

We analyze ColEmbed-3B-v2, the best-performing retriever we evaluated across query type, content modality, and query language.

Performance is aligned with query complexity

Figure˜5 shows that performance is inversely correlated with query complexity: simple query types such as Boolean and Numerical score significantly higher than Open-ended and Multi-hop queries. Question formulations consistently outperform Instruction and Keyword formats across nearly all categories, underscoring the need for improved handling of these query structures.

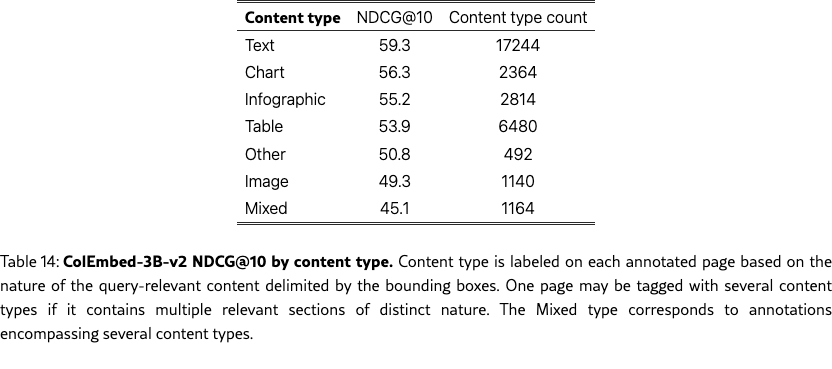

Visual Content and multi-page queries are hardest for retrievers

Figure˜6 highlights that queries involving visual content like tables or images tend to be more difficult. The Mixed content type scores the lowest, which suggests that integrating information across different modalities within a single page remains a challenge. Additionally, we observe a consistent decline in performance as the number of annotated pages increases (Figure˜7), suggesting that retriever effectiveness decreases when aggregating information from multiple sources is required.

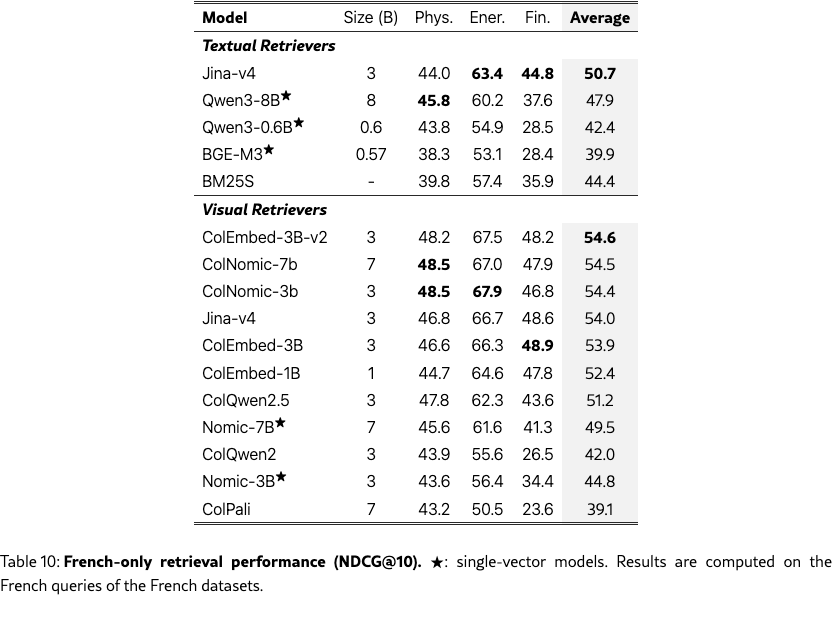

Cross-language queries degrade performance

Retrieval performance is 2–3 points higher in mono-lingual settings (Table˜9 and Table˜10) than cross-lingual settings (Table˜1), showing that models need to better adapt to these settings.

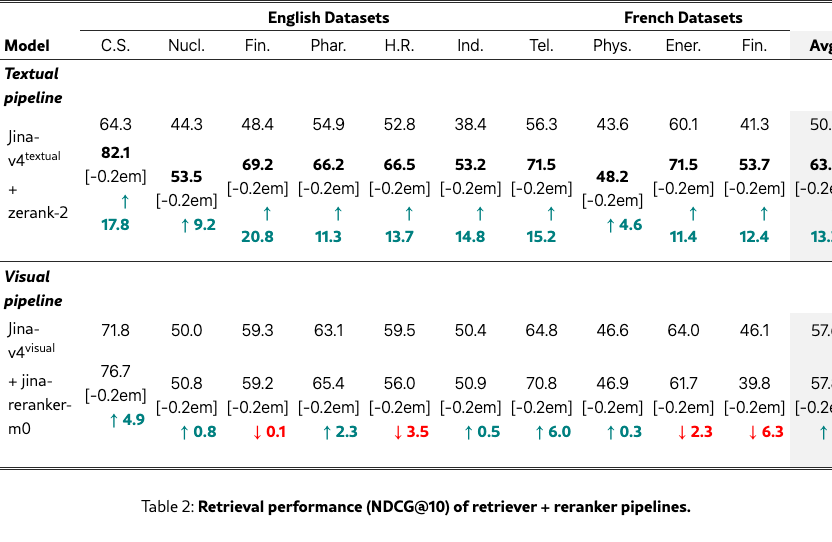

Textual rerankers outperform visual ones

We evaluate the impact of adding a reranker to the textual and visual pipelines of the Jina-v4 retriever. We select zerank-2 Zero Entropy (2025) and jina-reranker-m0 Jina AI (2025) as two of the leading textual and visual rerankers to date. Results in Table 2 reveal a significant disparity in reranking efficacy between modalities. While the visual retriever initially outperforms the textual base, the textual reranker yields substantial gains (+13.2 NDCG@10), enabling the textual pipeline to achieve the highest overall retrieval performance. In contrast, the visual reranker provides only a marginal average improvement of +0.2 and degrades performance in 4 datasets, underscoring the need for better multilingual visual rerankers.

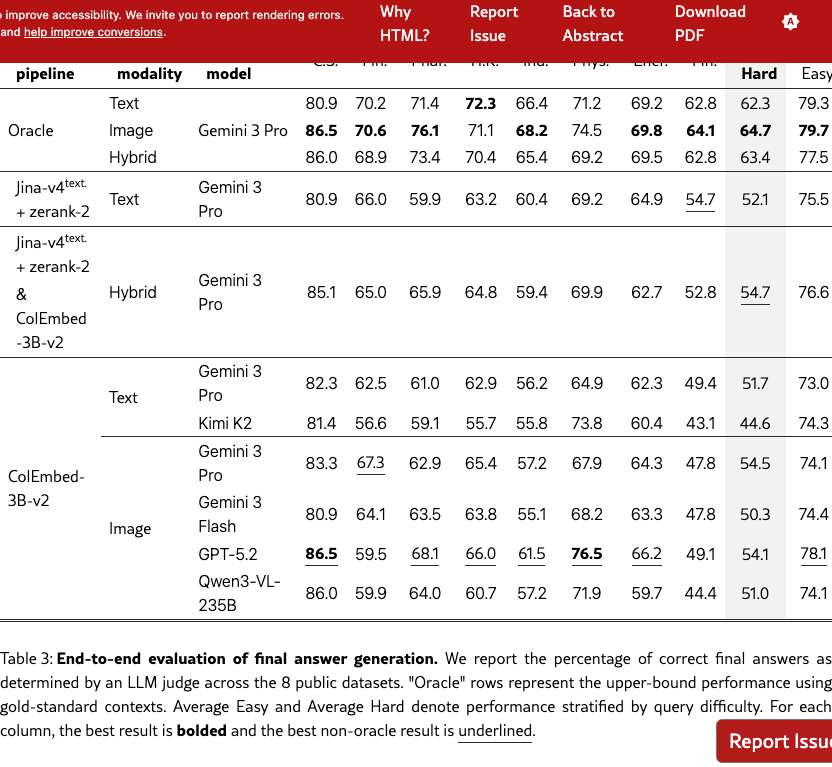

4.2 Final Answer Generation

We evaluate end-to-end answer quality by providing LLMs and VLMs with queries and their corresponding retrieved pages, examining the effects of retrieval pipeline selection, context modality, and generation model choice (Table˜3). For this evaluation, we use the best-performing textual and visual retrieval pipelines. We additionally establish an upper bound using an oracle pipeline that supplies the model with ground-truth annotated pages.

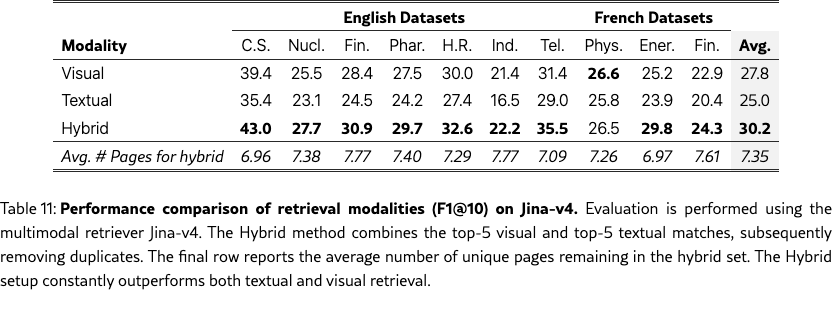

In the hybrid configuration, we concatenate the top-5 results from the visual retriever (images) with the top-5 results from the textual retriever (text), without removing duplicates; the retrieval performance is detailed in Table˜11. We also consider a hybrid oracle setup, which provides the model with all the ground-truth pages in both modalities.

The correctness of generated answers is assessed against the ground truth final answer by an LLM judge (details in Appendix H). Private datasets are omitted to maintain their integrity.

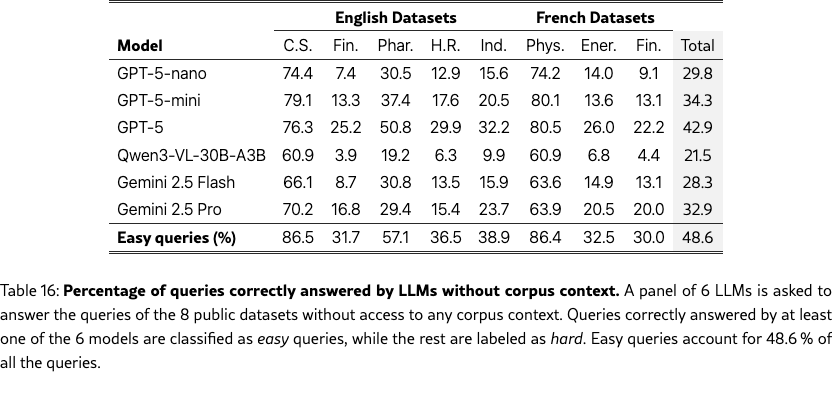

Some benchmark queries involve general knowledge manageable by LLMs without retrieval. To prevent memorization from confounding our assessment of the RAG pipeline, we stratify queries by difficulty based on parametric knowledge. A query is categorized as easy if any model in a 6-LLM panel answers it correctly without context; otherwise, it is labeled hard. Overall, 48.6 % of queries are easy (see Table˜16 for details).

Visual context helps generation

With a fixed Gemini 3 Pro generator, image-based context outperforms text-based context on the hard subset by 2.4 and 2.8 percentage points for the oracle and ColEmbed-3B-v2 pipelines, respectively (Table˜3). This confirms that preserving the visual content of document pages provides better grounding for complex answer generation.

Hybrid retrieval yields the best performance on challenging queries

The hybrid pipeline achieves 54.7 % accuracy on hard queries, surpassing both the strongest textual (52.1 %) and visual (54.5 %) baselines. This complementary effect suggests that text and image representations capture different aspects of document content, and their combination can provide more robust evidence for downstream generation.

Hard queries expose the limits of parametric knowledge in current models

Even with oracle context, performance on hard queries lags behind easy queries by more than 10 percentage points. This gap suggests that the multi-step reasoning and long-context synthesis required for difficult queries remain challenging for current models. While the models we evaluate achieve comparable overall scores, their relative ranking may shift when parametric knowledge is less of an advantage, as shown by GPT 5.2 outperforming Gemini 3 Pro on easy queries but trailing on hard ones.

ViDoRe V3 leaves significant room for future retriever improvements

The 10-point gap between the best non-oracle result (54.7 %) and the image oracle (64.7 %) on hard queries underscores substantial opportunities for improving the retrieval pipeline. Moreover, even with oracle contexts, Gemini 3 Pro performance remains modest, indicating that generation models still struggle to fully exploit the provided information.

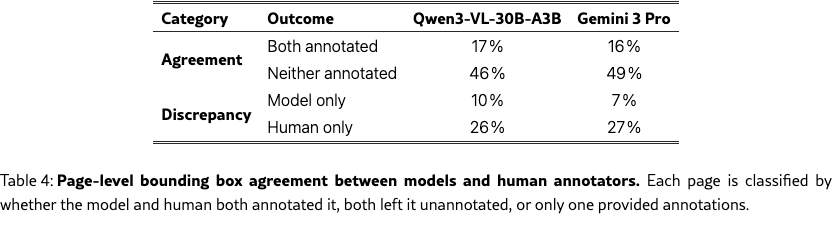

4.3 Visual Grounding

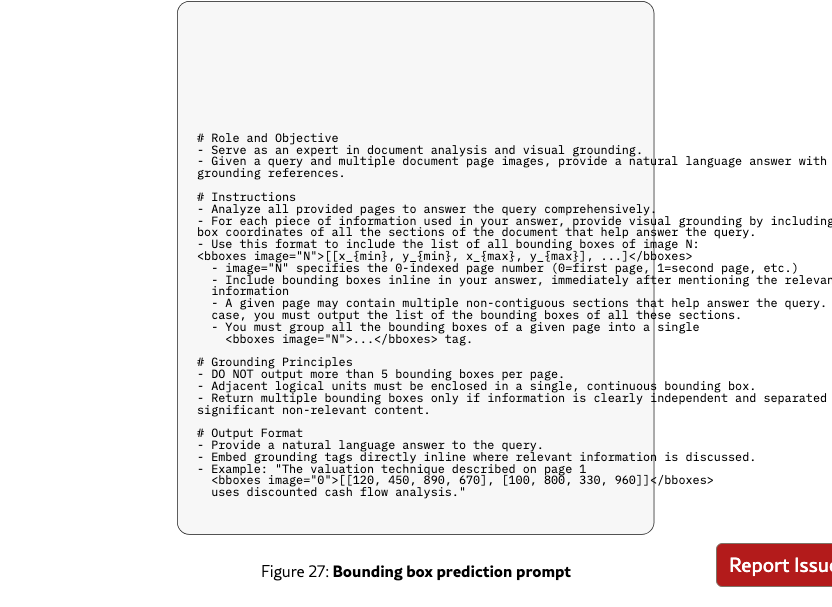

Beyond generating correct answers, it is highly desirable for RAG pipelines to identify where in the source documents the answer originates, enabling users to verify the grounding of the query answer. We therefore evaluate the ability of LLMs to generate accurate bounding boxes within their final answer. Among the few LLM families with visual grounding capabilities, we select Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B-Instruct and Gemini 3 Pro for evaluation. For each query, we provide the model with the candidate pages shown to the human annotators and prompt it to answer the query while inserting inline bounding boxes in XML format <bboxes image="N"> ... </bboxes> to delimit relevant content (full instructions in Appendix G).

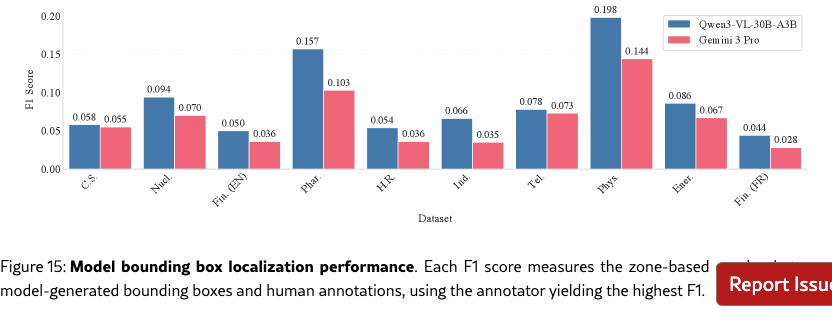

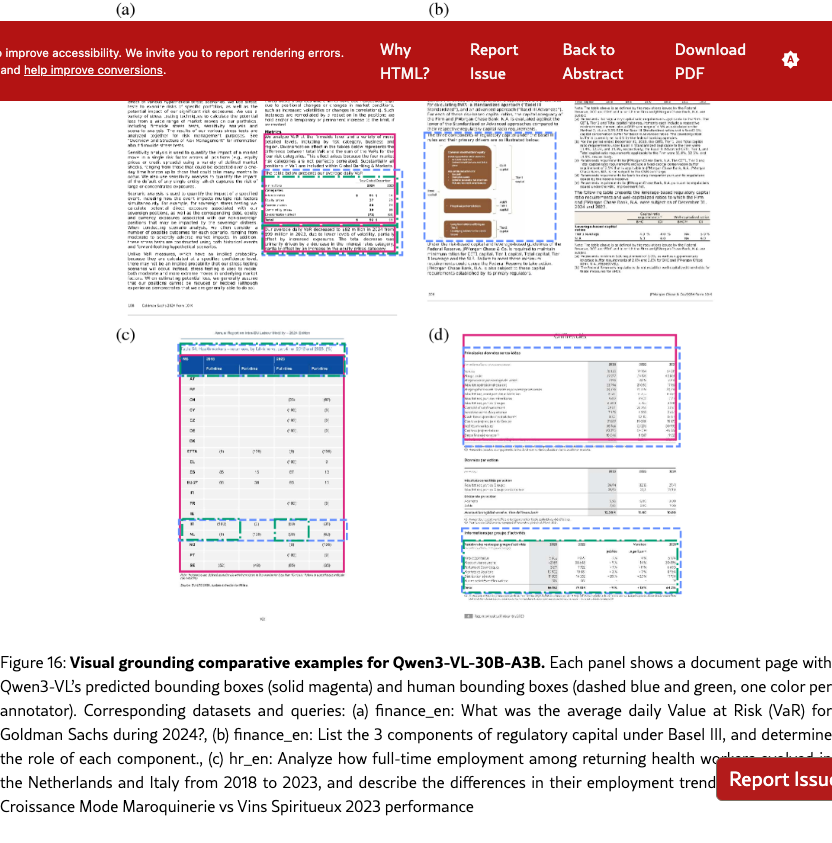

We use the bounding boxes produced by the human annotators as our ground truth. Since each query may have 1–3 human annotators, we evaluate VLM predictions independently against each annotator using the same zone-based methodology as the inter-annotator consistency analysis (Section 3.3), and report the highest F1 score. This best-match strategy reflects the inherent subjectivity of evidence selection: annotators may legitimately highlight different regions to support the same answer, and a model should not be penalized for matching any valid interpretation.

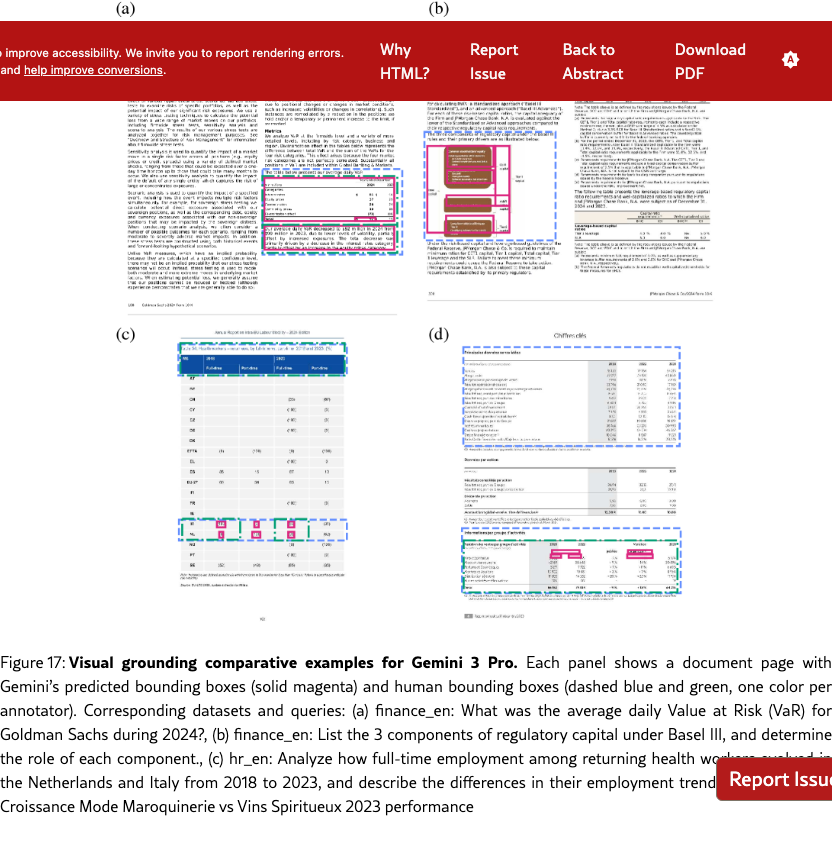

Visual grounding lags human performance

Inter-annotator agreement on evidence localization reaches an F1 of 0.602, whereas the best-performing models achieve markedly lower scores: 0.089 for Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B-Instruct and 0.065 for Gemini 3 Pro. A page-level analysis (Table˜4) reveals that on pages where humans provided bounding boxes, both models annotated the same page only 16–17 % of the time, while 26–27 % of human-annotated pages received no model annotation at all—highlighting recall as the primary bottleneck. Detailed per-domain results and qualitative analysis appear in Appendix G and 17.

5 Conclusion

This work introduces ViDoRe V3, a multilingual, human-annotated RAG benchmark that evaluates retrieval, final answer generation, and visual grounding on large industry-relevant document corpora. We design a human-in-the-loop annotation methodology, deployed in a 12,000-hour annotation campaign, that produces diverse realistic queries paired with relevant pages, bounding boxes, and reference answers. Evaluating state-of-the-art RAG pipelines, we find that visual retrievers outperform textual ones, late interaction and textual reranking yield substantial gains, and visual context improves answer generation quality. Looking ahead, ViDoRe V3 highlights several concrete research directions for practical multimodal RAG. Retriever models still struggle on cross-lingual and open-ended queries requiring visual interpretation, while VLMs need improvement in answer generation from multi-page contexts as well as accurate visual grounding. To drive progress in multimodal RAG, ViDoRe V3 has been integrated into the MTEB leaderboard, offering a rigorous framework that fosters the creation of more robust document understanding systems.

Limitations

Language coverage

While our benchmark is multilingual, it is restricted to English and French source documents and queries in 6 high-resource Western European languages. Future iterations of the benchmark should include a more diverse set of language families and non-Latin scripts to mitigate this bias.

Document distribution bias

Our benchmark focuses on publicly available long-form document corpora, representing one specific mode of existing document distribution. For example, enterprise RAG may need to handle a wider variety of document types, often in private repositories, that include noisy, short-form types such as emails, support tickets, or scanned handwritten notes that are not represented in our source documents.

Human annotation

Annotations for open-ended reasoning and visual grounding inherently contain a degree of subjectivity. We acknowledge that for complex exploratory queries, multiple valid retrieval paths and answer formulations may exist outside of our annotated ground truths.

Ethical considerations

Annotator Welfare and Compensation

Human annotation was conducted by the creators of the benchmark and a single external annotation vendor. Multiple established vendors were evaluated with respect to the annotation protocol and relevant ethical considerations, and one vendor was selected based on demonstrated compliance with these criteria. Annotators were recruited from the vendor’s existing workforce in accordance with the demographic requirements described in the Annotator Pool and Selection section (Appendix˜C) and were compensated at rates designed to provide fair pay based on geographic location and required skill sets. The data were curated such that annotators were not exposed to harmful or offensive content during the annotation process. The use of human annotators was limited to standard annotation and verification tasks for benchmark construction and did not constitute human-subjects research; accordingly, the data collection protocol was determined to be exempt from formal ethics review.

Data Licensing and Privacy

All documents included in the benchmark were manually selected from governmental, educational, and enterprise websites that met open license criteria. The annotations were collected in order not to contain any private or personally identifiable information and are GDPR-compliant. The benchmark is released under a commercially permissive license to facilitate broad research adoption while respecting the intellectual property rights of original document creators.

Linguistic and Geographic Bias

We acknowledge that our benchmark is restricted to English and French source documents and queries in 6 high-resource Western European languages. This limitation may inadvertently favor RAG systems optimized for these languages and does not reflect the full diversity of practical document retrieval scenarios globally. We encourage future work to extend evaluation to underrepresented language families and non-Latin scripts.

Environmental Impact

The creation of this benchmark required substantial computational resources for VLM pre-filtering, synthetic query generation, and model evaluation. We report these costs to promote transparency: approximately 12,000 hours of human annotation effort and extensive GPU compute for model inference across our evaluation suite. Specifically, the compute totaled 3,000 hours on NVIDIA H100 GPUs on a low emission energy grid, with an estimated environmental impact of 200 kg .

Detailed Contributions

Benchmark Design

Loison, Macé, Edy, Moreira and Liu designed the benchmark.

Data and Annotation

Loison and Macé developed the synthetic data generation pipeline. Loison generated the queries, while Macé predicted links between queries and pages. Loison, Macé, and Balough defined annotation guidelines; Balough coordinated the annotation campaign. Macé and Edy managed final answer merging. Loison, Macé, Edy, Xing, and Balough reviewed the final annotations.

Evaluation

Macé, Edy and Loison conceptualized the evaluations. Macé and Loison worked on retrieval evaluation, with Moreira focusing on the evaluation of ColEmbed models. Edy led the end-to-end evaluation, reranking analysis, and visualization. Macé and Edy integrated the results into the MTEB leaderboard. Xing led bounding box evaluations and result analysis.

Writing and Supervision

The manuscript was written by Loison, Macé, Xing, and Edy. Senior supervision and strategic guidance were provided by Xing, Faysse, Liu, Hudelot, and Viaud, with Faysse closely advising on project direction and planning.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted with contributions from NVIDIA. We thank all the people that allowed this work to happen, in particular Eric Tramel, Benedikt Schifferer, Mengyao Xu and Radek Osmulski, Erin Potter and Hannah Brandon. Crucially, we thank the dedicated team of annotators for their essential efforts.

It was carried out within the framework of the LIAGORA "LabCom", a joint laboratory supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR) and established between ILLUIN Technology and the MICS laboratory of CentraleSupelec. The benchmark was partially created using HPC resources from IDRIS with grant AD011016393.

References

- Ask in any modality: a comprehensive survey on multimodal retrieval-augmented generation. External Links: 2502.08826, Link Cited by: §1.

- Docling technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2408.09869. Cited by: §3.2.

- Qwen2.5-vl technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.13923. Cited by: §3.3.

- Density-based clustering based on hierarchical density estimates. In Pacific-Asia conference on knowledge discovery and data mining, pp. 160–172. Cited by: §3.2.

- GTE-moderncolbert. External Links: Link Cited by: Table 8.

- BGE M3-Embedding: Multi-Lingual, Multi-Functionality, Multi-Granularity Text Embeddings Through Self-Knowledge Distillation. arXiv. Note: Version Number: 3 External Links: Link, Document Cited by: Table 8.

- M3docrag: multi-modal retrieval is what you need for multi-page multi-document understanding. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.04952. Cited by: §1.

- M3DocRAG: multi-modal retrieval is what you need for multi-page multi-document understanding. External Links: 2411.04952, Link Cited by: §1, §2.

- Context is gold to find the gold passage: evaluating and training contextual document embeddings. External Links: 2505.24782, Link Cited by: §1.

- A survey on rag meeting llms: towards retrieval-augmented large language models. External Links: 2405.06211, Link Cited by: §1.

- ColPali: efficient document retrieval with vision language models. External Links: 2407.01449, Link Cited by: Table 8, Table 8, Table 8, §1, §2, §2, §4.1.

- Enabling large language models to generate text with citations. External Links: 2305.14627, Link Cited by: §1.

- Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: a survey. External Links: 2312.10997, Link Cited by: §1.

- Jina-reranker-m0: multilingual multimodal document reranker. Note: Accessed: 2025-12-22 External Links: Link Cited by: §4.1.

- Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. External Links: 2005.11401, Link Cited by: §1.

- LFM2 technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2511.23404. Cited by: Table 8.

- Introducing rteb: a new standard for retrieval evaluation. External Links: Link Cited by: §3.5.

- BM25S: orders of magnitude faster lexical search via eager sparse scoring. External Links: 2407.03618, Link Cited by: Table 8.

- Unifying multimodal retrieval via document screenshot embedding. External Links: 2406.11251, Link Cited by: §2.

- VISA: retrieval augmented generation with visual source attribution. External Links: 2412.14457, Link Cited by: §1.

- SmolVLM: redefining small and efficient multimodal models. External Links: 2504.05299, Link Cited by: Table 8.

- InfographicVQA. External Links: 2104.12756, Link Cited by: §2.

- Docvqa: a dataset for vqa on document images. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF winter conference on applications of computer vision, pp. 2200–2209. Cited by: §1, §2.

- UMAP: uniform manifold approximation and projection for dimension reduction. External Links: 1802.03426, Link Cited by: §3.2.

- Mteb: massive text embedding benchmark. In Proceedings of the 17th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 2014–2037. Cited by: §1.

- NeMo data designer: a framework for generating synthetic data from scratch or based on your own seed data. Note: https://github.com/NVIDIA-NeMo/DataDesignerGitHub Repository Cited by: §3.2.

- Nomic embed multimodal: interleaved text, image, and screenshots for visual document retrieval. Nomic AI. External Links: Link Cited by: Table 8, Table 8, Table 8, Table 8.

- NVIDIA ingest: an accelerated pipeline for document ingestion. External Links: Link Cited by: §4.1.

- UNIDOC-bench: a unified benchmark for document-centric multimodal rag. External Links: 2510.03663, Link Cited by: §1, §2.

- Qwen3 technical report. External Links: 2505.09388, Link Cited by: §3.2.

- Bright: a realistic and challenging benchmark for reasoning-intensive retrieval. arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.12883. Cited by: §2.

- Fantastic (small) retrievers and how to train them: mxbai-edge-colbert-v0 tech report. External Links: 2510.14880, Link Cited by: Table 8.

- MultiHop-rag: benchmarking retrieval-augmented generation for multi-hop queries. External Links: 2401.15391, Link Cited by: §1, §2.

- ModernVBERT: towards smaller visual document retrievers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.01149. Cited by: Table 8.

- FreshStack: building realistic benchmarks for evaluating retrieval on technical documents. External Links: 2504.13128, Link Cited by: §1, §2.

- Document understanding dataset and evaluation (dude). In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 19528–19540. Cited by: §2.

- Vidorag: visual document retrieval-augmented generation via dynamic iterative reasoning agents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.18017. Cited by: §2.

- Charxiv: charting gaps in realistic chart understanding in multimodal llms. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 37, pp. 113569–113697. Cited by: §2.

- REAL-mm-rag: a real-world multi-modal retrieval benchmark. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12342. Cited by: §2.

- Llama nemoretriever colembed: top-performing text-image retrieval model. External Links: 2507.05513, Link Cited by: Table 8, Table 8, Table 8, §2.

- VisRAG: vision-based retrieval-augmented generation on multi-modality documents. External Links: 2410.10594, Link Cited by: §2.

- BBox docvqa: a large scale bounding box grounded dataset for enhancing reasoning in document visual question answer. External Links: 2511.15090, Link Cited by: §2.

- Introducing zerank-2. Note: Accessed: 2025-12-22 External Links: Link Cited by: §4.1.

- Qwen3 embedding: advancing text embedding and reranking through foundation models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.05176. Cited by: Table 8, Table 8, §3.2.

- Towards complex document understanding by discrete reasoning. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, pp. 4857–4866. Cited by: §2.

Appendix A Dataset examples

Appendix B Supplementary benchmark details

Domains

Table˜6 details the type of documents used in each corpus as well as several statistics.

Query type and format descriptions

Query type by generation method

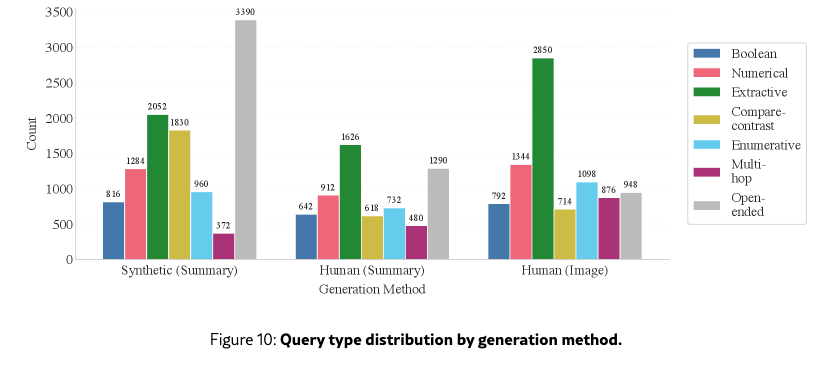

Query type distributions by generation method (Figure 10) confirm that open-ended queries dominate synthetic queries as the synthetic pipeline attributed more weight to this type, while extractive queries dominate human-image queries since they are more naturally chosen by annotators.

Appendix C Annotator pool and training details

Annotator Pool and Selection.

Annotation was conducted by a curated pool of 76 annotators who were selected based on having: (1) a bachelor’s degree or higher in the relevant domain, (2) professional experience in the domain, (3) native-level language proficiency as required by task, and (4) prior experience with RAG, retrieval, or VQA annotation projects. Quality control was performed by 13 senior annotators with enhanced domain knowledge and extensive annotation experience, with project oversight provided by data leads with multiple years of experience in human data generation.

Training and Pilot Phase.

The annotation process began with a comprehensive onboarding phase where annotators received task-specific training using gold-standard examples. For each domain, a pilot of several hundred tasks was conducted with 100% quality control coverage and multiple annotators per task. During this phase, data leads and the research team continuously evaluated annotations, provided clarifications, and refined guidelines. Inter-annotator agreement and time-per-task baselines were calculated to establish ongoing evaluation benchmarks. The pilot concluded upon validation of both data quality and guideline effectiveness.

Appendix D Supplementary agreement metrics

Pages were pre-filtered by a VLM before human annotation; as most pages shown to annotators were likely relevant, this created a skewed class distribution. This prevalence imbalance causes traditional chance-corrected metrics like Krippendorff’s Alpha to appear paradoxically low even when annotators genuinely agree, as inflated expected chance agreement penalizes the score. To address this, we report 2 complementary metrics: Krippendorff’s Alpha (ordinal) as the standard measure and Gwet’s AC2 which remains stable under prevalence skew. Overall, annotators achieved , AC2 . The divergence between Alpha and AC2/Weighted Agreement is expected given the pre-filtered data and confirms substantial agreement despite the skewed distribution.

Appendix E Supplementary retrieval details

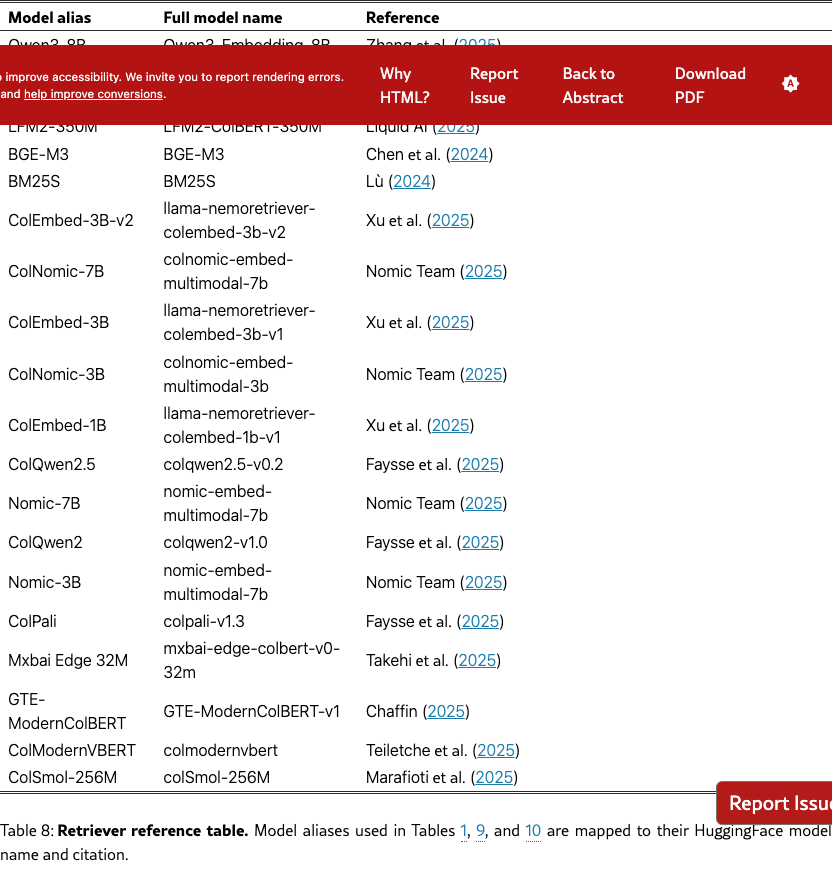

Retriever model reference

Table 8 lists the retriever models evaluated in this work, along with their HuggingFace model names and citations.

Monolingual performance

Tables 9 and 10 present the monolingual performance of our models, where retrieval is conducted using language-matched queries and documents for English and French, respectively.

Additional Retrieval Modality Performances

To evaluate the hybrid retrieval setup, we use the multimodal Jina-v4 model to generate separate visual and textual rankings. We then construct a hybrid retrieval set by merging the top-5 results from each modality and removing duplicates. Because this set-union operation does not preserve a strict ranking order, we report the unranked F1 score. As shown in Table˜11, the hybrid approach consistently outperforms single-modality baselines.

Appendix F ColEmbed-3B-v2 performance breakdown

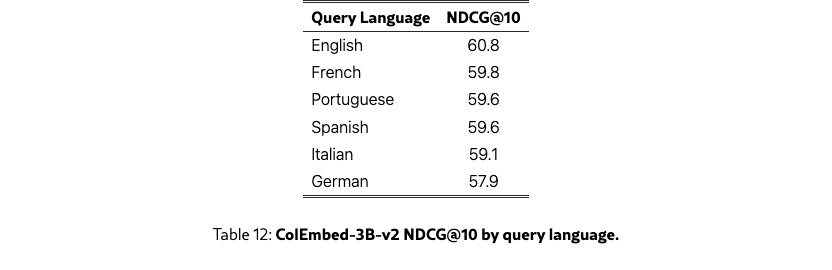

Table˜12 details the retrieval scores of ColEmbed-3B-v2 by query language, highlighting small performance variations by language.

Performance by number of annotated pages

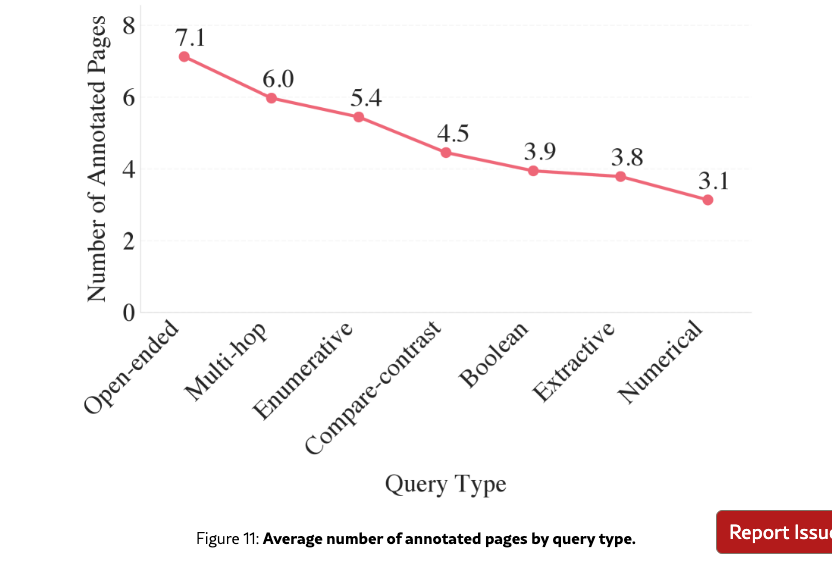

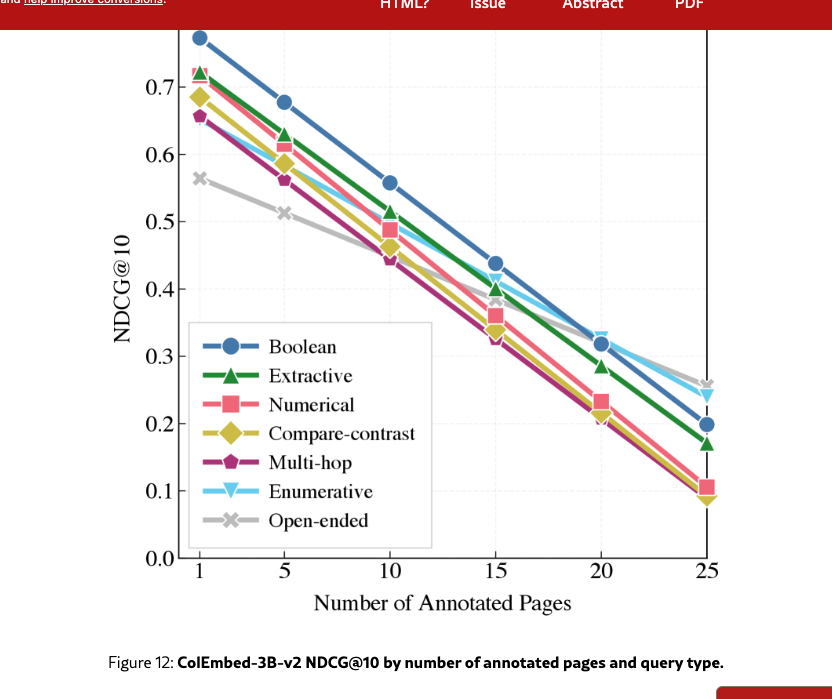

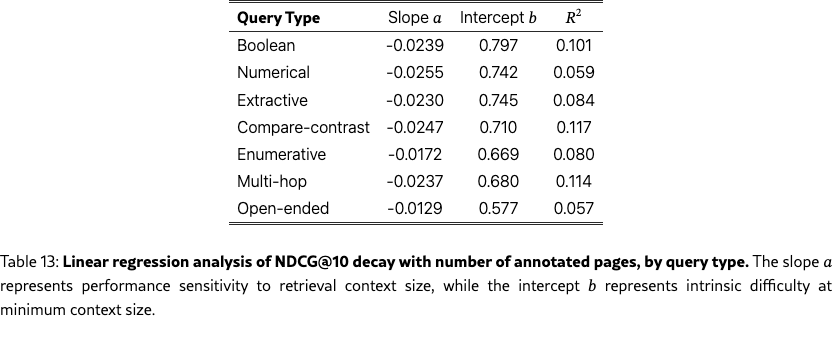

As seen in Figure 7, performance drops with the number of annotated pages. However, a potential confounding factor is the correlation between query type and the number of annotated pages, since more complex query types also have higher number of annotated pages (Figure 11). We perform a stratified regression analysis to isolate these two effects.

We model NDCG@10 as a linear function of the number of annotated pages () stratified by query type. For each of the 7 query types, we fit an ordinary least squares regression:

Results in Figure 12 and Table 13 reveal that all query types suffer a significant performance penalty as the number of annotated pages increases. Slope values are nearly uniform (), suggesting a similar drop in retrieval accuracy across most query types. The open-ended and enumerative types are the two exceptions: despite having the lowest NDCG@10 for low page counts, they also have the shallowest slope, which suggests that retrieval success on these queries is constrained by the model’s fundamental difficulty in synthesizing multiple relevant sources rather than the volume of relevant context.

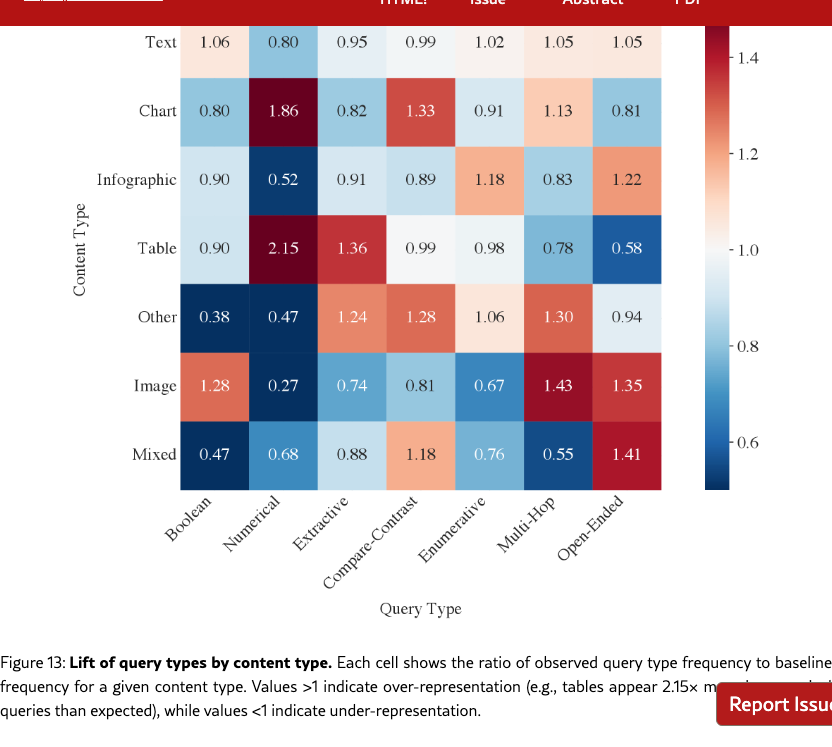

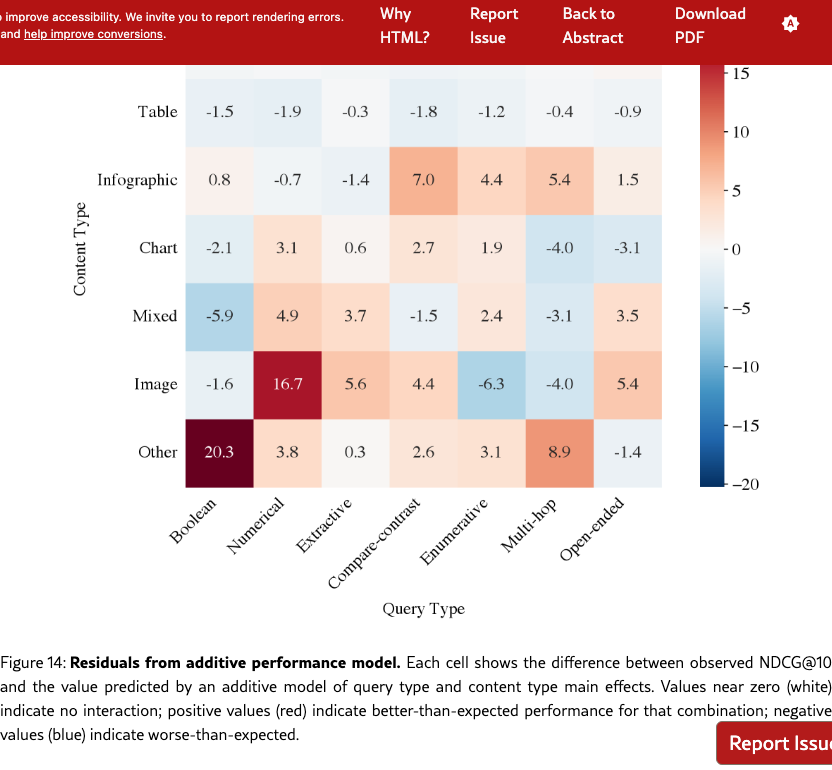

Performance by content type

NDCG@10 by content type in Table 14 show that retrieval is more challenging for visual content, with Image performing 10pp below Text. However, content type and query type are correlated in our benchmark: for instance, tables appear in numerical queries 2.2 more often than the baseline, while images are over-represented in open-ended queries (Figure 13). Since numerical queries are easier than open-ended ones, we test whether the effect of content type is a byproduct of query type confounding. We fit an additive model that predicts performance as the sum of independent query-type and content-type effects. Figure 14 shows the residuals which measure deviation from this baseline. We see that most residuals are below 5pp, indicating that the two factors combine additively without significant interaction.

Appendix G Bounding box annotations

Inter-annotator agreement

Bounding box predictions

Figure 27 shows the prompt used to generate final answers with inline bounding boxes for visual grounding, and Figure 15 reports bounding box localization F1 scores by dataset.

Appendix H Final answer evaluation

Evaluation setup

Generated final answers are evaluated in a pass@1 setting using GPT 5.2 with medium reasoning effort as the LLM judge. The judge compares each generated answer against the ground-truth annotation and returns a binary correctness label. The answer generation and judge prompts are shown in Figure 25 and Figure 24 respectively. We evaluated Gemini 3 Pro with low thinking effort, GPT-5 with medium reasoning effort, as well as the thinking version of Qwen3-VL-235B-A22B.

To assess the reliability of our judge, we conducted 5 independent evaluation runs on a fixed set of Gemini 3 Pro outputs. Individual run scores showed minimal fluctuation (mean 72.09 %, %) and high internal consistency (Krippendorff’s ), confirming that the judge is consistent given a fixed context.

End-to-End Pipeline Stability

While the judge demonstrates high consistency on fixed inputs, the full evaluation pipeline introduces a second layer of variability: the model’s generation process. To quantify the end-to-end variance under rigorous conditions, we performed 5 independent runs. For computational efficiency, we restricted this stress test to the most challenging corpus in each language: Industrial Maintenance (English) and Finance (French).

We measured an average score of 65.74 % with a standard deviation of 0.94 %. Crucially, the evaluation signal remains robust against generative noise, achieving a Krippendorff’s of 0.80. This agreement confirms that the end-to-end results are statistically reliable even when subjected to the most difficult evaluation scenarios.

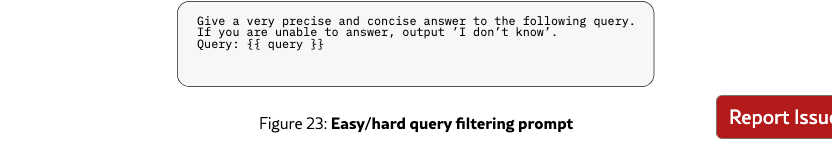

Easy/hard query filtering

To classify queries by difficulty, we prompt a panel of 6 LLMs to answer each query without access to any corpus context. We select GPT-5-nano, GPT-5-mini, GPT-5, Qwen3-VL-30B-A3B, Gemini 2.5 Flash, and Gemini 2.5 Pro to span different model families and capability levels. Each model receives only the query text and is asked to provide a direct answer with the prompt in Figure 23. Answers are evaluated for correctness using the same GPT-5.2 judge described above. A query is labeled easy if at least one model answers correctly, and hard otherwise. Table 16 reports per-model accuracy and the resulting proportion of easy queries for each dataset. The distribution varies substantially across domains: knowledge-intensive datasets such as Computer Science and Physics have over 85% easy queries, while domain-specific datasets such as Finance and Energy contain fewer than 35% easy queries, reflecting the specialized nature of their content.

Appendix I Visual grounding examples

Qualitative analysis reveals distinct failure modes. Gemini frequently produces off-by-one page indexing errors: the predicted coordinates would correctly localize the target content if applied to an adjacent page. The two models also differ in box granularity: Gemini tends to draw tight boxes around individual elements (e.g., a single table cell or text line), whereas Qwen3-VL generates larger boxes encompassing entire sections or paragraphs, more closely matching human annotation patterns. Figures 16 and 17 illustrate these tendencies across four dataset pages: Qwen3-VL’s bounding boxes are comparatively wide and encompass entire page elements (pages (a), (c), and (d)), while Gemini 3 Pro’s visual grounding is more precise (pages (b) and (c)). This difference in granularity partially explains Qwen3-VL’s higher F1 scores, as broader boxes are more likely to overlap with the ground-truth zones used in our evaluation. Both models exhibit errors and omissions: in page (b), the chart is not labeled by Qwen3-VL, and in page (d), Gemini 3 Pro predicts incorrect bounding boxes for the bottom table while Qwen3-VL provides grounding for the wrong table.

Appendix J Instructions given to Annotators

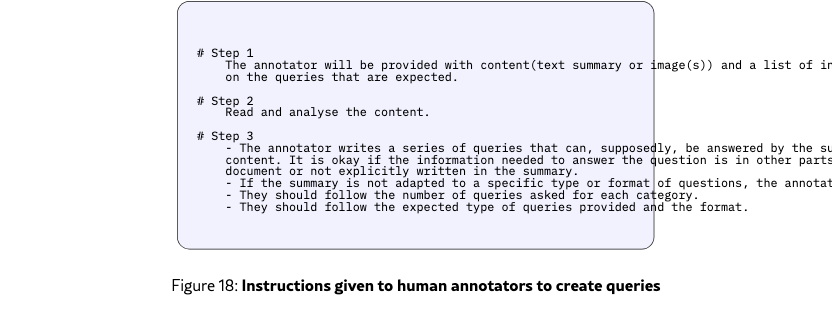

Query Generation

Figure˜18 details step-by-step instructions to annotators to generate queries from summaries and images.

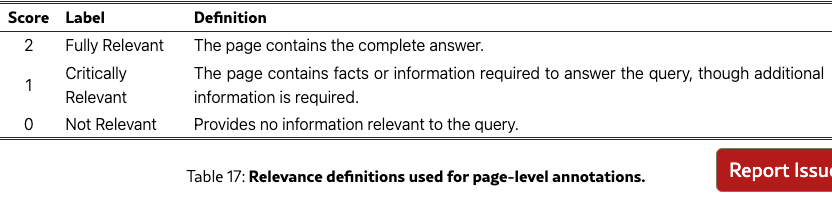

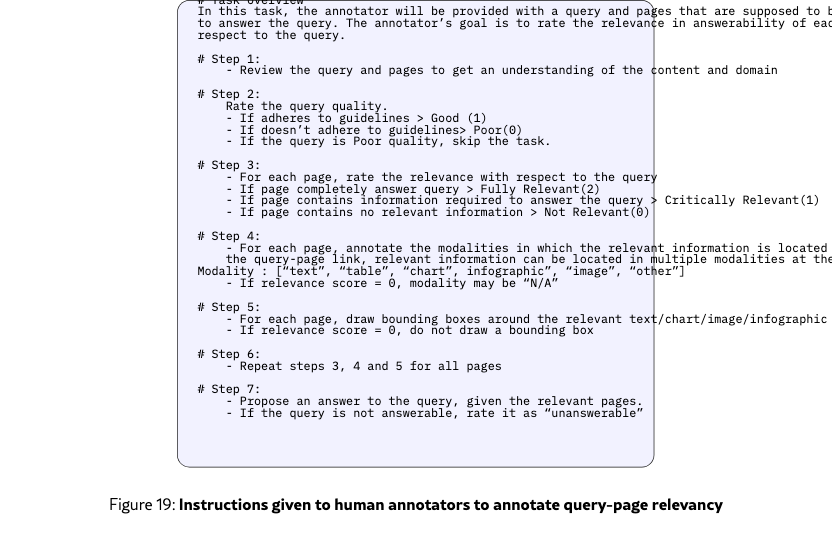

Query-Page Relevancy linking

Figure˜19 details the step-by-step instructions provided to annotators for assessing page relevance, identifying content modalities, and localizing evidence via bounding boxes. Table˜17 gives the definitions of relevancy scores used by the human annotators.

Appendix K Prompts

All the prompts used for both dataset generation and evaluations are detailed from Figure˜20 to Figure˜27.