Verbalized Sampling: How to Mitigate Mode Collapse and Unlock LLM Diversity

Abstract

Post-training alignment often reduces LLM diversity, leading to a phenomenon known as mode collapse. Unlike prior work that attributes this effect to algorithmic limitations, we identify a fundamental, pervasive data-level driver: typicality bias in preference data, whereby annotators systematically favor familiar text as a result of well-established findings in cognitive psychology. We formalize this bias theoretically, verify it on preference datasets empirically, and show that it plays a central role in mode collapse. Motivated by this analysis, we introduce Verbalized Sampling (VS), a simple, training-free prompting strategy to circumvent mode collapse. VS prompts the model to verbalize a probability distribution over a set of responses (e.g., “Generate 5 jokes about coffee and their corresponding probabilities”). Comprehensive experiments show that VS significantly improves performance across creative writing (poems, stories, jokes), dialogue simulation, open-ended QA, and synthetic data generation, without sacrificing factual accuracy and safety. For instance, in creative writing, VS increases diversity by 1.6-2.1 over direct prompting. We further observe an emergent trend that more capable models benefit more from VS. In sum, our work provides a new data-centric perspective on mode collapse and a practical inference-time remedy that helps unlock pre-trained generative diversity.

1 Introduction

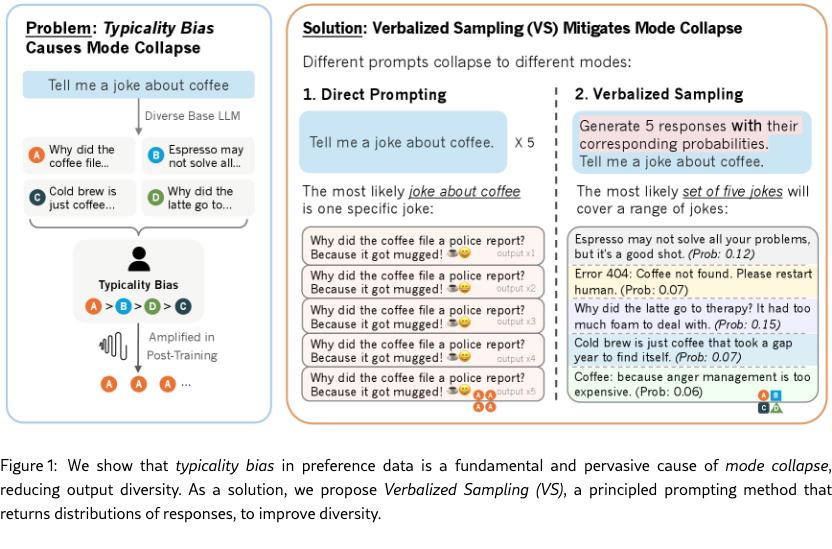

Post-training alignment methods like RLHF can unintentionally cause mode collapse (Janus, 2022; O’Mahony et al., 2024; Kirk et al., 2024b), whereby the model favors a narrow set of responses (the “mode”) over all plausible outputs, as shown in Figure 1. This significantly reduces output diversity (Padmakumar & He, 2024; West & Potts, 2025) and limits LLMs’ effectiveness in various applications such as creative writing (Lu et al., 2025b), social simulation (Anthis et al., 2025b), pluralistic alignment (Kirk et al., 2024a), and synthetic data generation (Zhu et al., 2025a).

Existing work often attributes mode collapse to algorithmic causes such as inadequate reward models (Chakraborty et al., 2024) or the majority-favoring optimization process (Xiao et al., 2024). In this paper, we show that the issue is more fundamental: mode collapse is an inherent property of preference data itself. We identify typicality bias, the human tendency to prefer more typical text, as a pervasive data-level cause for mode collapse. Critically, this means that even with a perfect reward model and optimization process, inherent bias within preference datasets may still drive mode collapse, affecting the majority of alignment methods that rely on reward models. In Section 3, we formalize this concept with an analytical model, corroborated by empirical verification on preference datasets, to confirm the central role of typicality bias.

As typicality bias is pervasive across human preference data, we look for solutions beyond the training process. Grounded in our theoretical insights, we propose a simple but principled prompting method to bypass mode collapse. As shown in Figure 1, instead of a traditional, direct prompt asking for a single instance (e.g., “tell me a joke about coffee”), we reformulate the prompt to explicitly ask the model to verbalize a distribution of responses with corresponding probabilities (e.g., “generate 5 responses with their probabilities”). We call our method Verbalized Sampling (VS). Intuitively, VS works because different prompts collapse to different modes. The modal response to a traditional instance-level prompt tends towards stereotypicality. By contrast, when prompted for a distribution in VS, the modal response tends to approximate the distribution learned during pretraining, recovering the diversity of the underlying base model. Figure 2 shows a ready-to-use VS prompt.

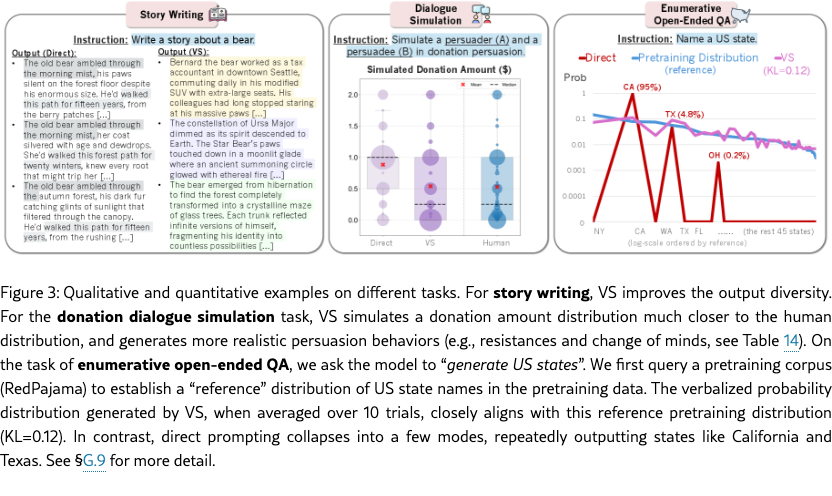

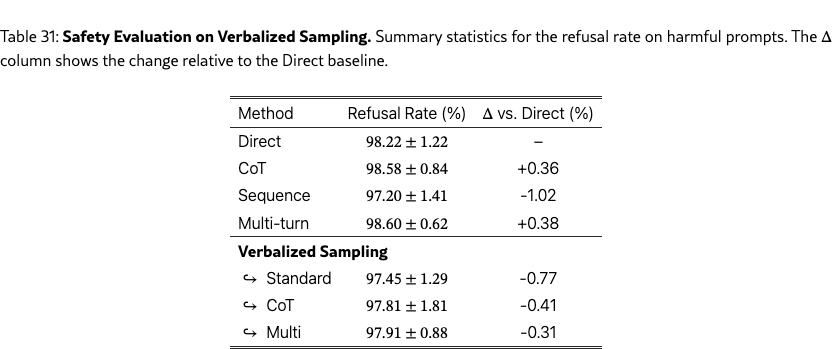

Building on this foundation, we conduct comprehensive experiments across creative writing (poem, joke, story generation, §5), social dialogue simulation (§6), open-ended QA tasks (§7), and synthetic data generation (§8). As shown in examples in Figure 3, we find that (1) on creative writing, Verbalized Sampling significantly improves output diversity; (2) on social dialogue simulation, VS induces substantially more human-like behaviors, with some models performing on par with a dedicated fine-tuned model; (3) on open-ended QA tasks with multiple valid answers, it generates a broader and more realistic response distribution, and (4) on synthetic data generation, VS generates more diverse synthetic data that improves downstream math task performance. We also confirm that VS improves performance without sacrificing the models’ factual accuracy (§G.7) or safety (§G.8). To summarize, we contribute the following:

-

1.

Novel Cause of Mode Collapse. We provide a new theoretical framework to understand mode collapse, and identify and verify typicality bias in empirical preference data as a key cause. This finding offers a new, data-driven perspective for analyzing the behavior of aligned models.

-

2.

Training-Free Solution. Informed by our theoretical understanding, we introduce a principled prompting method, Verbalized Sampling, that explicitly asks for a distribution of responses and verbalizes its corresponding probabilities, restoring LLMs’ inherent generative diversity.

-

3.

Empirical Gains. We perform comprehensive experiments that show VS significantly improves the diversity-quality trade-off across tasks and model families, without compromising factual accuracy and safety. For instance, in creative writing, VS boosts diversity by 1.6-2.1 over direct prompting (Figure 4), improves human evaluation scores by 25.7% (Table 3), and recovers 66.8% of the base model’s diversity (Figure 7). We also observe an emergent trend that more capable models benefit more from VS. These results open up possibilities in real-world tasks such as richer exploration in RL, hypothesis generation, social simulation, and so on.

-

4.

Broader Implications for Alignment. Our work shows that mode collapse can be mitigated at inference time, aligned models retain significant inherent diversity, and the quality-diversity trade-off can be systematically improved through prompting alone.

2 Related Work

Mode Collapse and Alignment.

Previous studies (Padmakumar & He, 2024; West & Potts, 2025) have observed that compared to their base counterparts, aligned models suffer from mode collapse, a significant drop in output diversity. Lu et al. (2025b) quantified this issue, showing that the creative capacity of LLMs diminishes after alignment. Existing research has primarily attributed this phenomenon to algorithmic limitations (Casper et al., 2023). Chakraborty et al. (2024) suggested that it is inadequate to rely on a single reward model to capture diverse human preferences, while Xiao et al. (2024) showed that the KL-regularized optimization used in RLHF tends to amplify common, majority-style responses. The issue is compounded further by practices even before alignment: for instance, SFT can lead to overfitting and limited diversity due to its cross-entropy loss function, and rigid chat templates further restrict its creativity (Yun et al., 2025). Our work complements existing studies by introducing a fundamental data-driven perspective, where we identify a pervasive data bias (i.e., typicality bias) that exacerbates the algorithmic causes of mode collapse.

Methods to Improve Diversity.

Previous efforts to improve LLM diversity include training interventions (Chung et al., 2025; Zhou et al., 2025), decoding strategies (Vijayakumar et al., 2016; Holtzman et al., 2020; Lanchantin et al., 2025; Tian et al., 2023b) and prompting methods Han et al. (2022); Yang et al. (2022b; a). For example, Ismayilzada et al. (2025) introduced an alignment method for multifaceted creativity preferences. Decoding techniques like -sampling (Hewitt et al., 2022), mirostat (Basu et al., 2021), REAL-sampling (Chang et al., 2025) and min-p sampling (Nguyen et al., 2025) improve diversity by regulating the text perplexity during generation. However, these methods are either computationally expensive or restricted to open-sourced models. While prompting-based techniques offer a lightweight alternative (Summers-Stay et al., 2023; Mehrotra et al., 2024; Tian et al., 2025), they often rely on prescriptive, handcrafted prompts (Zhang et al., 2024b; Shur-Ofry et al., 2024; Ge et al., 2025; Lu et al., 2025c; Wong et al., 2024; Spangher et al., 2025). In contrast, our verbalized sampling is training-free, simple but principled, and broadly applicable.

Another line of work also uses LLMs to generate lists of responses or verbalize their knowledge in tasks like question answering (Tian et al., 2023a; Xiong et al., 2024; Tao et al., 2024), commonsense reasoning (Zhang et al., 2024a), survey simulations (Meister et al., 2024) and synthetic data generation (Wang et al., 2023a; Si et al., 2024). These methods mainly focused on empirical observation without theoretical grounding to fully leverage this verbalizing strategy; our work proves that verbalizing the distribution and probabilities is the key towards diversity improvement, and our VS method enhances the performance over all baselines and also allows output diversity tuning.

3 Typicality Bias Causes Mode Collapse

In this section, we show that typicality bias in human preference data is one pervasive cause of mode collapse. This bias sharpens the probability distribution towards a few stereotypical completions. When many high-quality completions are possible (e.g., in joke generation), this sharpening becomes a tie-breaker, resulting in mode collapse.

3.1 Typicality Bias in Preference Data: Cognitive & Empirical Evidence

Typicality Bias Hypothesis.

Cognitive psychology shows that people prefer text that is familiar, fluent, and predictable. This preference is rooted in various principles. For instance, the mere‑exposure effect (Zajonc, 1968; Bornstein, 1989) and availability heuristic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1973) imply that frequent or easily recalled content feels more likely and is liked more. Processing fluency (Alter & Oppenheimer, 2009; Reber et al., 2004) suggests that easy-to-process content is automatically perceived as more truthful and higher quality. Moreover, schema congruity theory (Mandler, 2014; Meyers-Levy & Tybout, 1989) predicts that information that aligns with existing mental models will be accepted with less critical thought. We therefore hypothesize that these cognitive tendencies lead to a typicality bias in preference data, in which annotators systematically favor conventional text.

Modeling Rewards with Typicality Bias.

To capture this hypothesized bias, we model the reward function, which reflects human preferences, as a combination of true task utility and typicality bias. For a tractable proxy of typicality bias, we employ the log-likelihood from a pretrained base model, : as the base model has been trained to maximize likelihood on massive text corpora, its probability scores inherently capture text typicality. Without loss of generality, we use the Bradley-Terry model common in RLHF (Bradley & Terry, 1952; Christiano et al., 2017; Ouyang et al., 2022) and formulate this combination in reward models in Eq. 1:

| (1) |

where is the true task utility, is the typicality bias weight, and is a noise term. means that, holding the true utility fixed, higher typicality bias increases the reward.

Verifying Typicality Bias in Preference Data.

We test this hypothesis on HelpSteer (Wang et al., 2023b), a preference dataset which provides per-response ratings for both correctness (true task utility) and overall helpfulness (the final reward). From the training set, we form pairs of responses to the same prompt with the same correctness ratings. We then compute their per-token log-likelihoods under both Llama 3.1 405B Base and GLM 4.5 Base, the base models used as . Fitting these values to Eq. 1, yields and with the respective base models (both ). This provides empirical evidence for a positive in Eq. 1, i.e., human raters are biased towards responses more typical for the base model, independent of correctness (true task utility). See §E.1 and §E.2 for the verification experiments on more preference datasets.

3.2 How Typicality Bias Causes Mode Collapse

Having confirmed typicality bias, we need to show how it leads to mode collapse. The RLHF optimization objective under the Bradley-Terry model is as follows,

| (2) |

where is the KL coefficient, is the reference policy (e.g., the base model), and is the learned policy.

Plugging Eq. 1 into the closed-form solution of Eq. 2 (Rafailov et al., 2024) yields an optimum, sharpened by (derivation in §E.3):

| (3) |

So any positive typicality bias weight strictly sharpens the distribution of . Leaving all else fixed, larger (stronger typicality in preference data) increases the strength of this effect.

Further, suppose there exists a subset of responses such that for all 111For example, we can restrict our analysis to with only meaningful responses, because nonsensical or erroneous responses are unlikely to be sampled from a well-trained . we have flat true rewards, 222This assumption can be relaxed to approximate flatness. We just need bounds on the deviations of between and to claim mode collapse, but the overall argument (and result) is consistent. . Then by Eq. 3 the optimum within reduces to

This behaves like temperature scaling. As grows very large, we will have for all with . This shows that the probability mass is compressed toward typical completions (those already favored by ), yielding a form of mode collapse on set . Intuitively this means that, when many answers are tied on true task utility (a common scenario in creative writing, social simulation, etc), typicality bias acts as a tiebreaker that sharpens the output of the aligned model into the mode of the base model.

4 Method: Verbalized Sampling

We have shown that for a mode-collapsed model, any response on , which suggests the need to study the base model . Empirical studies (West & Potts, 2025; Zhu et al., 2025a) have shown that base models do exhibit diversity. Therefore, we propose Verbalized Sampling as a prompting strategy to recover the diversity level of , to bypass mode collapse.

4.1 Different Prompts Collapse to Different Modes

For a mode-collapsed LLM, we find that different prompts collapse to different modes of . This is how VS can mitigate mode collapse. We categorize prompting strategies into three types and provide their corresponding modes. Detailed assumptions and proof are provided in §E.4.

-

1.

Instance-level prompt: This is the most traditional prompt , requesting one instance (e.g., “Tell me a joke about coffee”). The mode is the mode instance (the mode joke) of the base model.

- 2.

-

3.

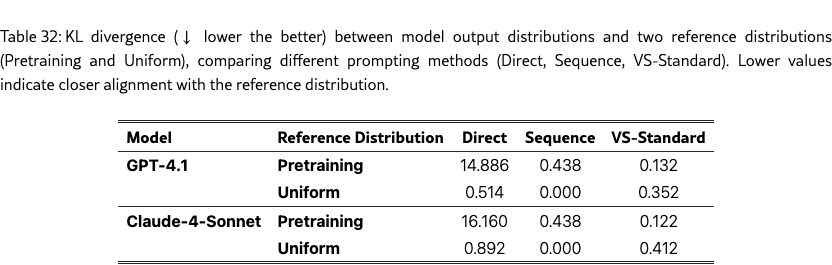

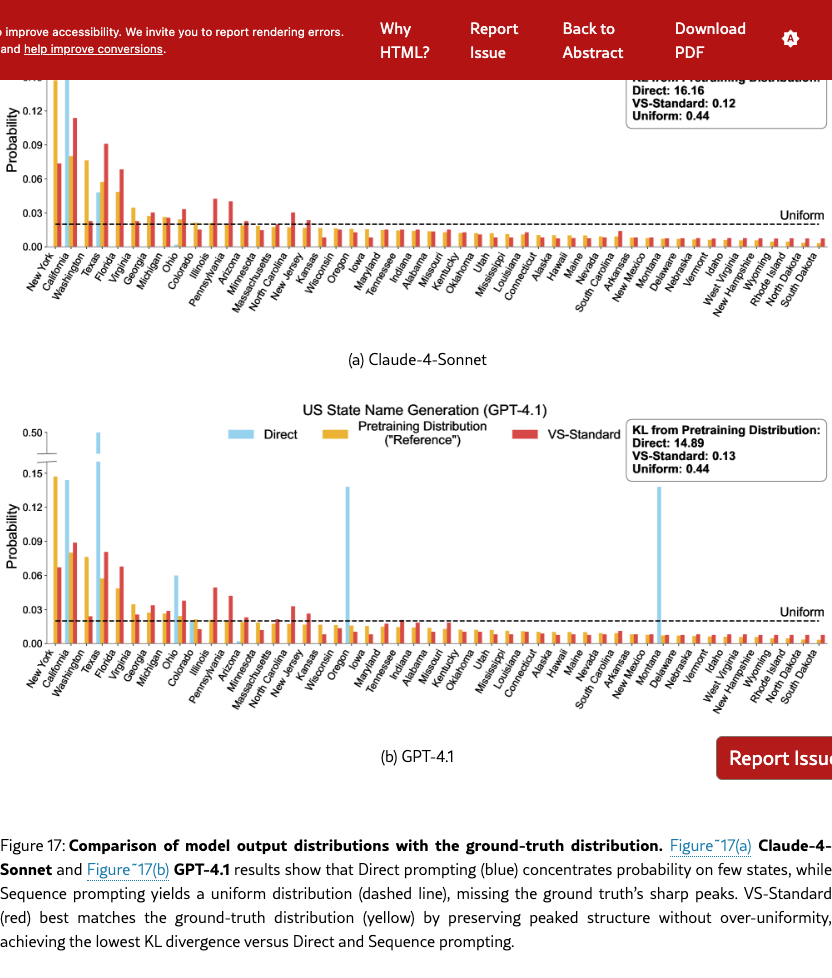

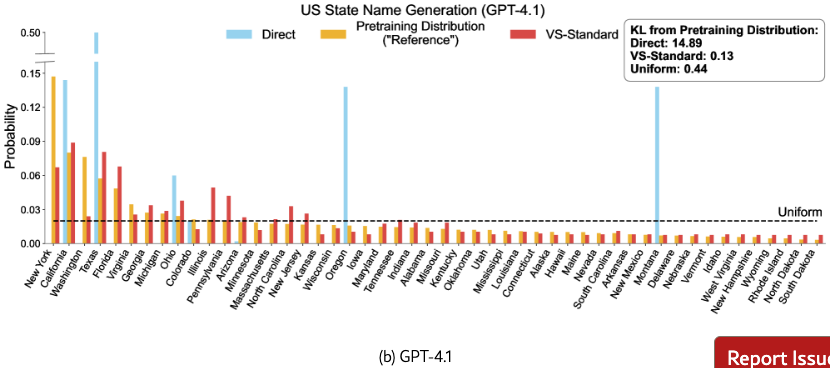

Distribution-level prompt (ours): We propose this prompt which requests outputs with corresponding probabilities (e.g., “Tell jokes about coffee with their probabilities”), and name it Verbalized Sampling (VS). The mode is a distribution capable of approximating the distribution of related items learned by the base model during pretraining. Figure 3 and §G.9 show that when an LLM is prompted to generate a distribution of the 50 US states, its verbalized probability distribution aligns with a proxy of the same distribution in a pre-training corpus (RedPajama), where the KL divergence is 0.12 for Claude-4-Sonnet.

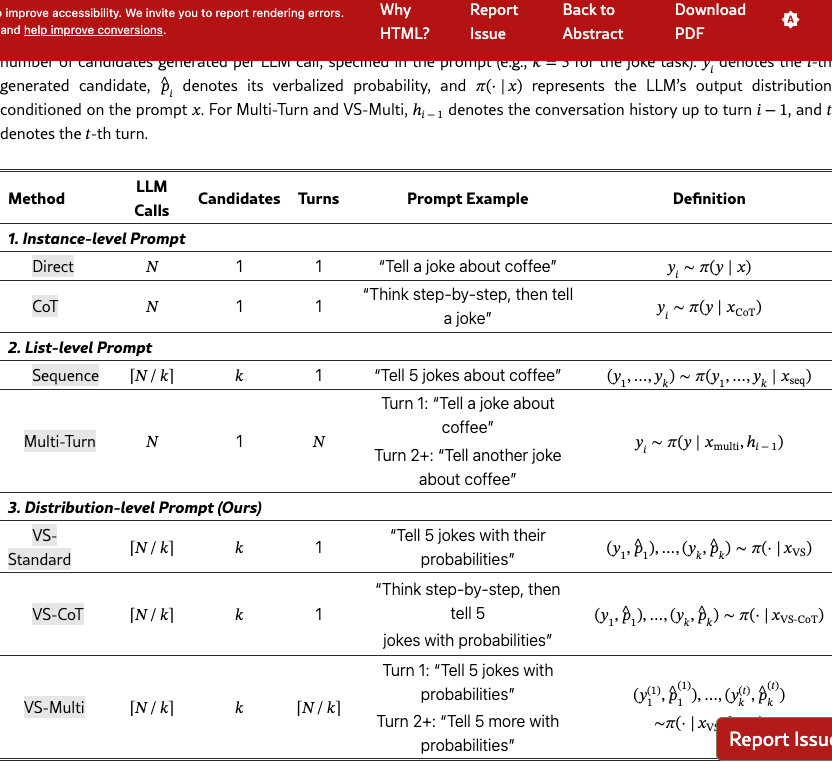

In Table 1, we summarize how to implement different prompting methods in practice, under the same computation budget of total generated responses for a fair comparison. In theory, the number of candidates in each LLM call could be equal to ; but in practice, we notice that if is too large, the generation quality degrades, so usually and we will generate total responses across calls. For (2) List-level prompt, we test another variant, multi-turn (West & Potts, 2025), which elicits responses across turns in a conversation. For (3) Distribution-level prompt, we propose two variants: VS-CoT and VS-Multi, to further enhance diversity.

4.2 Experimental Setup

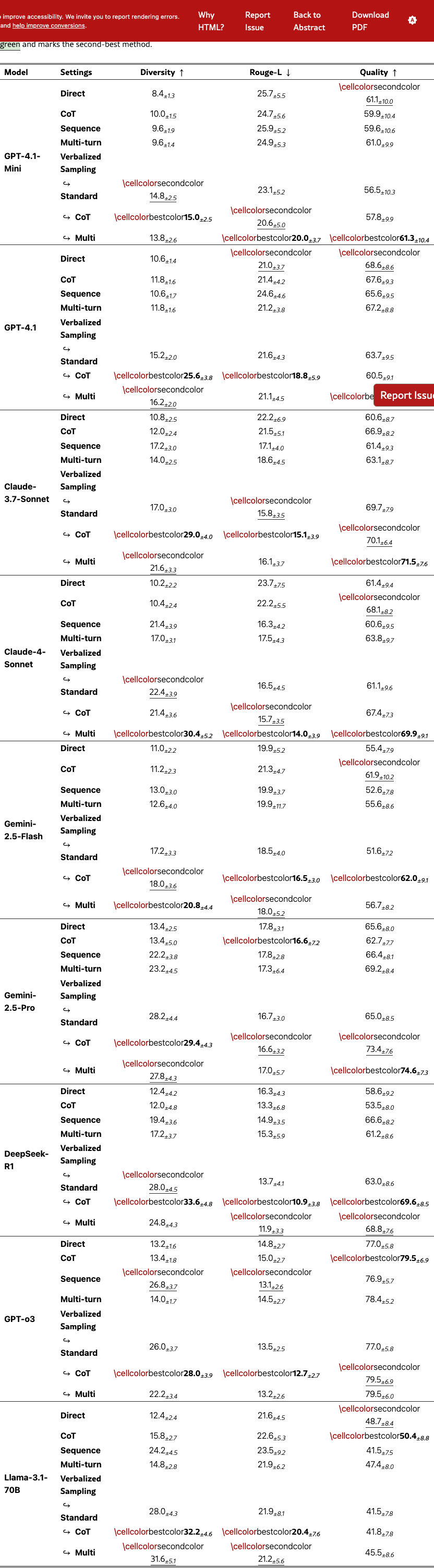

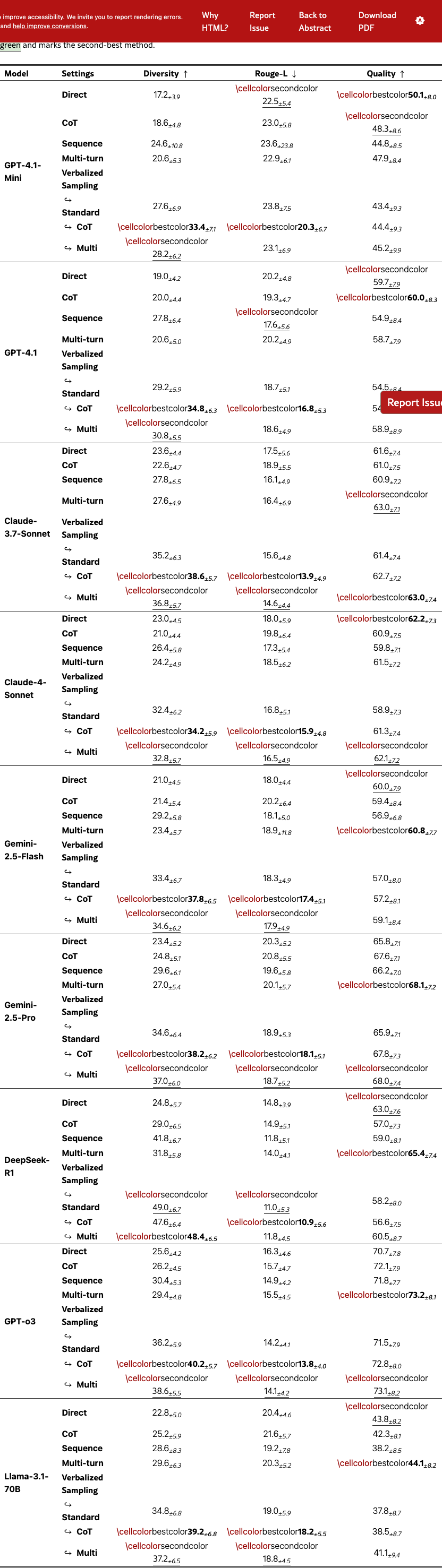

LLMs.

Our method is training-free, model-agnostic, and requires no logit access. We test it on a suite of models: (1) closed models like GPT Series (GPT-4.1-mini, GPT-4.1), Gemini Series (Gemini-2.5-Flash, Gemini-2.5-Pro) and Claude Series (Claude-3.7-Sonnet, Claude-4-Sonnet); (2) open ones like Llama-3.1-70B-Instruct and Qwen3-235B-A22B-2507-Instruct-2507; and (3) reasoning models like OpenAI o3 and DeepSeek R1. See §I.1 for generation hyperparameters.

Tasks.

We conduct comprehensive experiments on creative writing (§5), dialogue simulation (§6), open-ended QA (§7), synthetic data generation (§8 and §G.6.2), random number generation (§G.5), along with commonsense reasoning (§G.7) and safety (§G.8) to show that our method maintains factual accuracy and safety.

5 Creative Writing

Following prior work on LLM diversity (Lu et al., 2025b), we first study three creative writing tasks: poem continuation, story generation, and joke writing.

Benchmarks.

We evaluate model performance on three benchmarks. For (1) poem continuation and (2) story generation, we follow the text continuation setup in Lu et al. (2025b), and use poems from PoemHunter.com and stories from the BookMIA dataset (Shi et al., 2024) for experiments. For (3) joke writing: we follow Turgeman et al. (2025) and curate 100 thematic prompts from the Reddit r/DadJokes dataset (Reddit, 2023), each structured as “Write me a joke about [topic]” (e.g., “…about an octopus”). To reduce computation costs, we randomly select 100 data points for these three tasks, and apply verbalized sampling to generate candidates and total samples for each data point. Detailed prompts are provided in Section˜I.2.

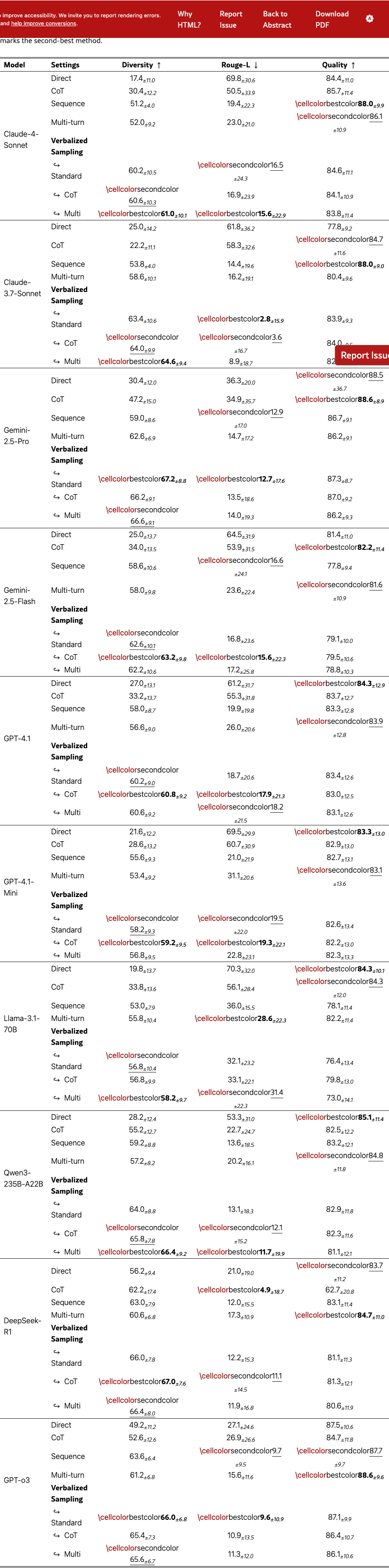

Evaluation.

We evaluate all methods on two metrics: diversity and quality. (1) For diversity, we assess both semantic and lexical levels: (i) For semantic diversity, we follow prior work (Cox et al., 2021; Cann et al., 2023; Lu et al., 2025b; Zhu et al., 2025a; Meincke et al., 2024) and calculate , where is the mean pairwise cosine similarity of response embeddings (generated using OpenAI’s text-embedding-3-small model). Negative similarities are clipped to 0 to avoid inflating diversity and we present the final score as a percentage, where 100% represents maximum diversity. (ii) For lexical diversity, we follow Shaib et al. (2025) and use ROUGE-L (Lin, 2004), where lower scores indicate greater diversity. (2) To evaluate output quality, we use Claude-3.7-Sonnet as the judge. We score Poem and Story with the rubrics from Creative Writing v3 (Paech, 2023), and jokes with the Humor grader rubrics from HumorBench (Narad et al., 2025a). See Section˜I.3 for details on evaluation.

5.1 Results

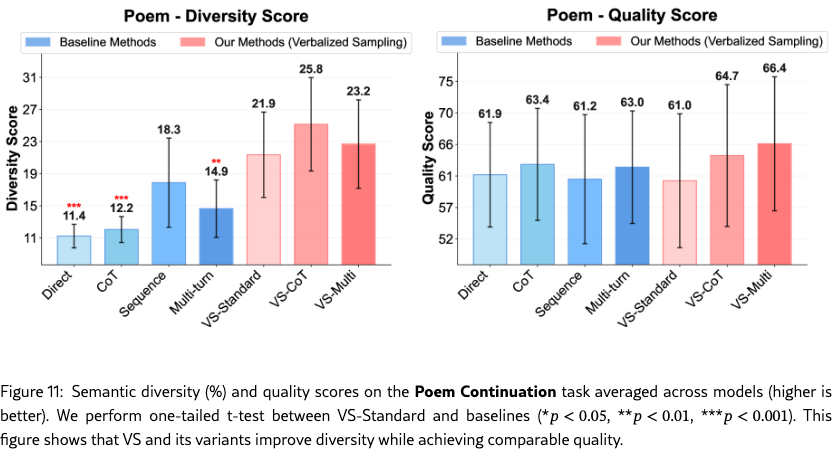

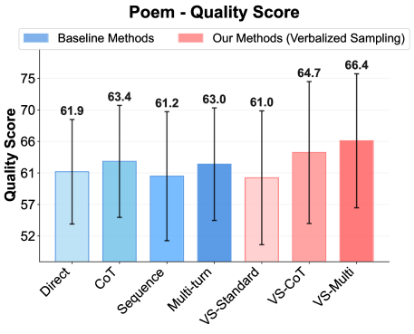

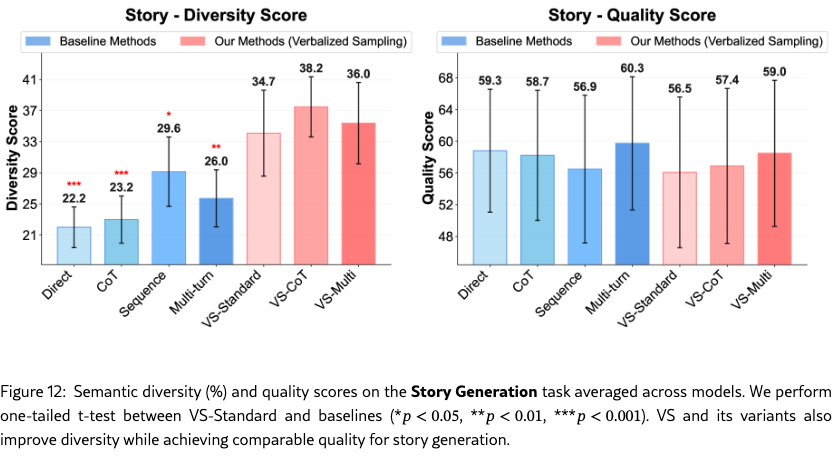

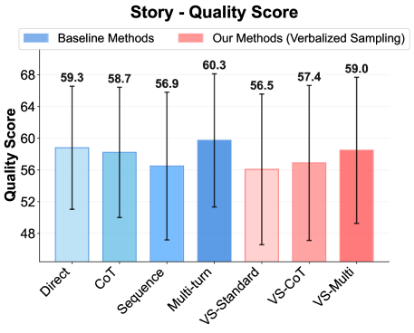

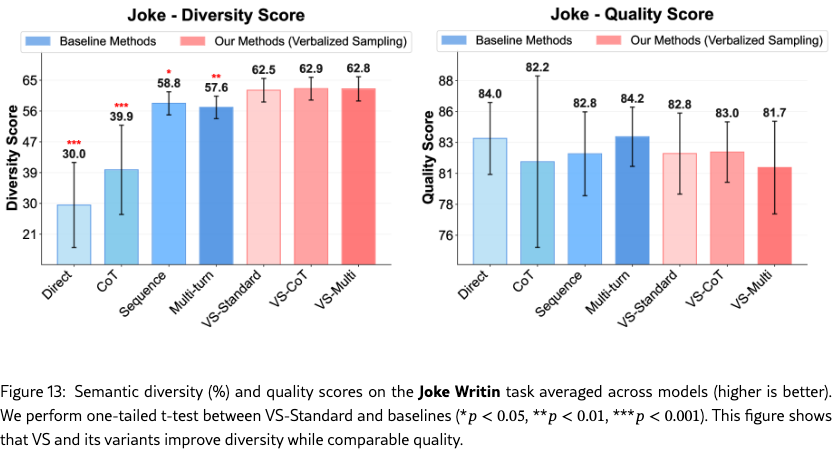

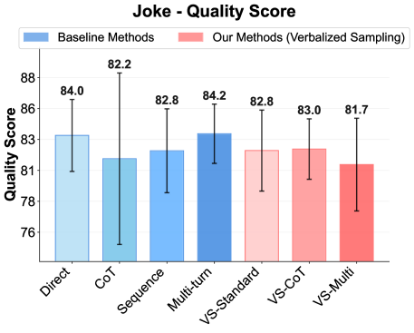

Diversity Score.

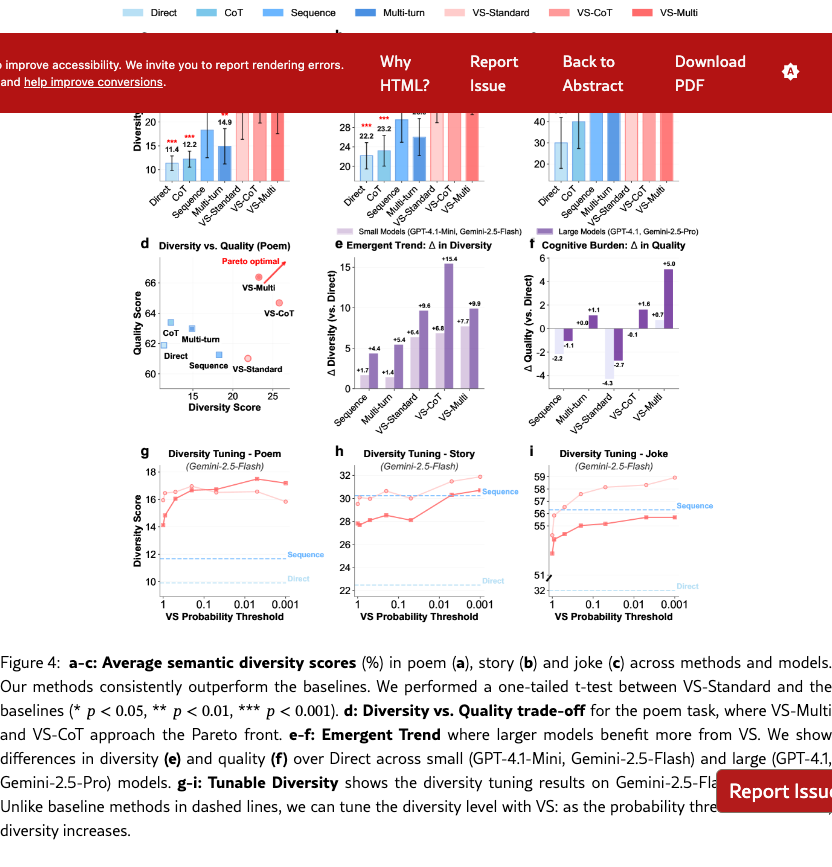

Figure 4(a)-(c) show the semantic diversity score averaged across models on poem, story, and joke, respectively. Across tasks, VS-Standard consistently and significantly outperforms baseline methods. The variants, VS-CoT and VS-Multi, further improve generation diversity. Detailed results on lexical diversity and individual model families are in Section˜G.1.1.

Diversity vs. Quality.

Figure˜4(d) shows the diversity-quality trade-off on the poem task. The quality of VS-Standard remains comparable to other methods. Notably, VS-CoT achieves the highest diversity while maintaining a high quality score, pushing the Pareto front of this trade-off (Zhang et al., 2021). This shows that VS can boost diversity without harming quality. See Section˜G.1 for the diversity-quality trade-offs for the story and joke tasks.

Emergent Trend.

We observe an emergent trend where larger models benefit more from VS. LABEL:{fig:creativity_main}(e) shows the diversity gain over the direct prompting which suffers from mode collapse. Across all VS variants, larger models (GPT-4.1, Gemini-2.5-Pro) achieve diversity gains 1.5 to 2 times greater than smaller models (GPT-4.1-Mini, Gemini-2.5-Flash).

Cognitive Burden.

This scaling trend also extends to quality, as shown in Figure˜4(f). While prior work (Hu et al., 2024) found complex prompts create a “cognitive burden” that degrades LLM performance, our findings are nuanced. Methods like Sequence and VS-Standard do cause a drop in quality, but this effect is less severe for larger models. Notably, more intricate variants like VS-CoT and VS-Multi overcome this burden, even improving quality in larger models. This suggests using VS variants may better utilize the capabilities of advanced models, turning complexity into benefits.

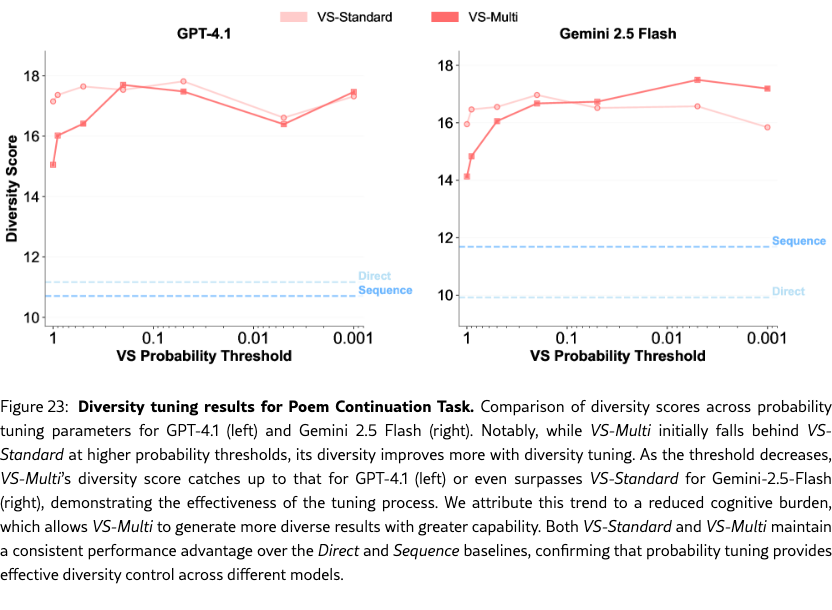

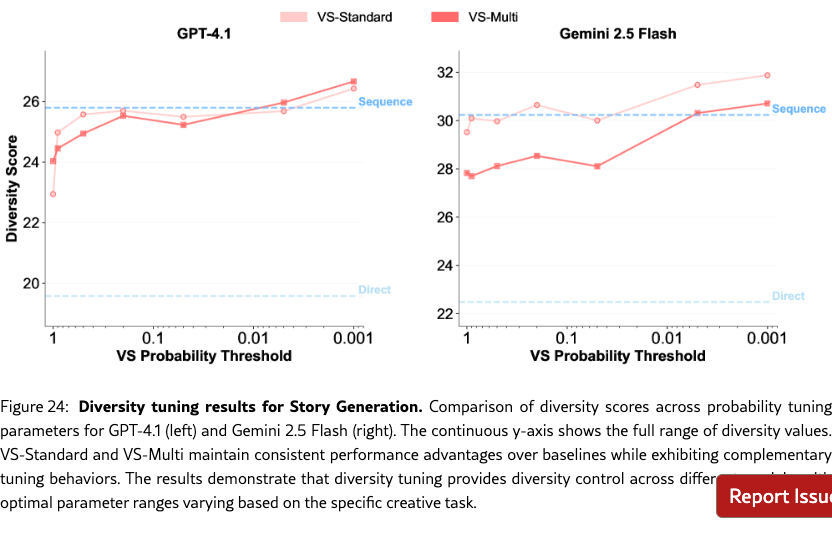

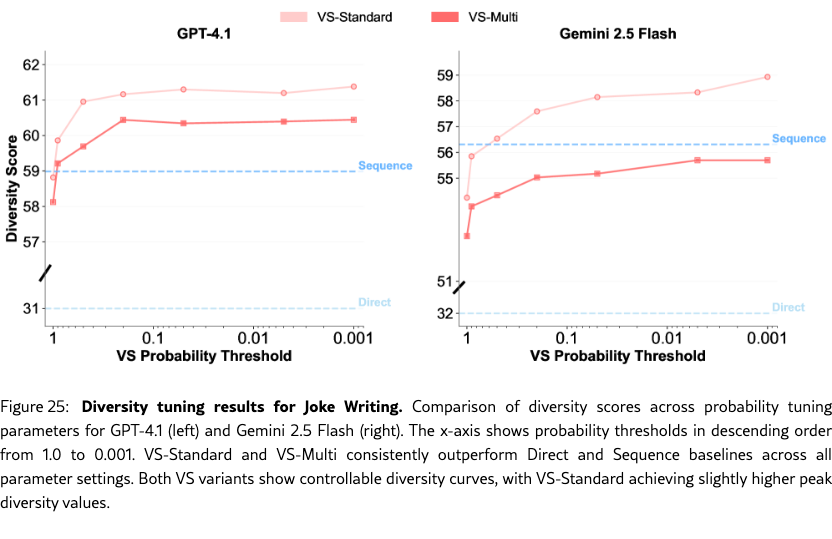

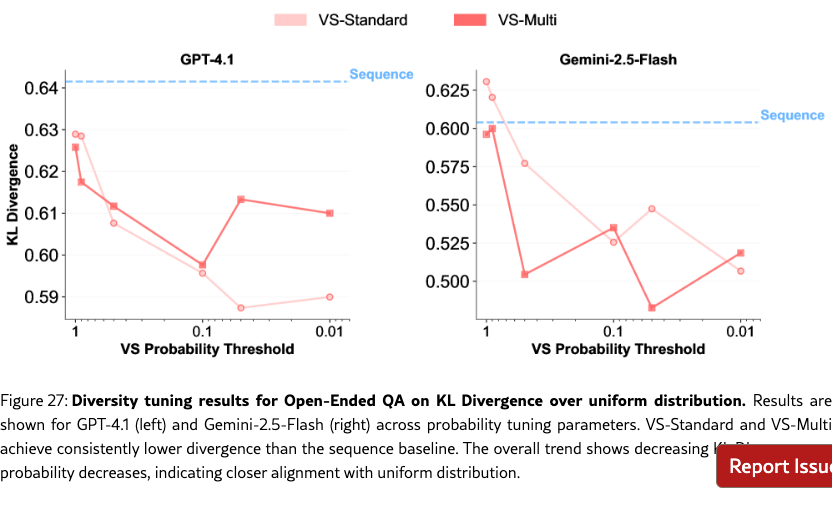

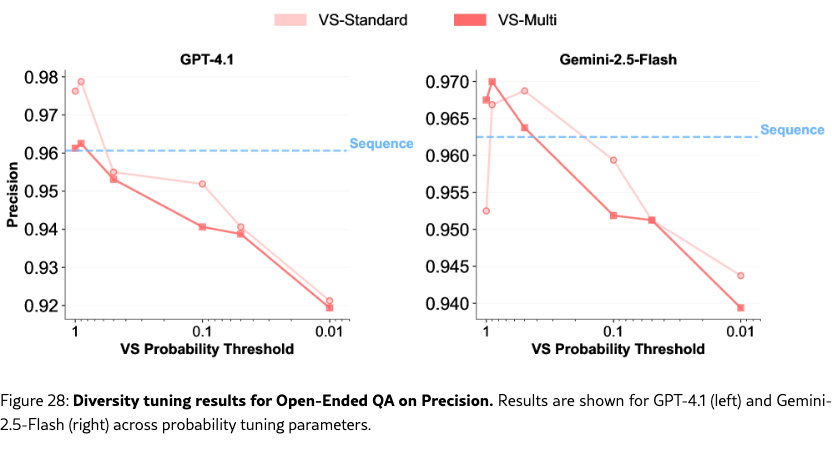

Diversity Tuning.

Unlike baseline methods, VS allows us to tune the output diversity by adjusting the probability threshold directly in the prompt (e.g., “Generate five responses with probabilities below {threshold}”), without altering decoding parameters. As shown in Figure˜4(g-i), diversity increases as the probability threshold decreases. See Section˜H.4 for more detailed results.

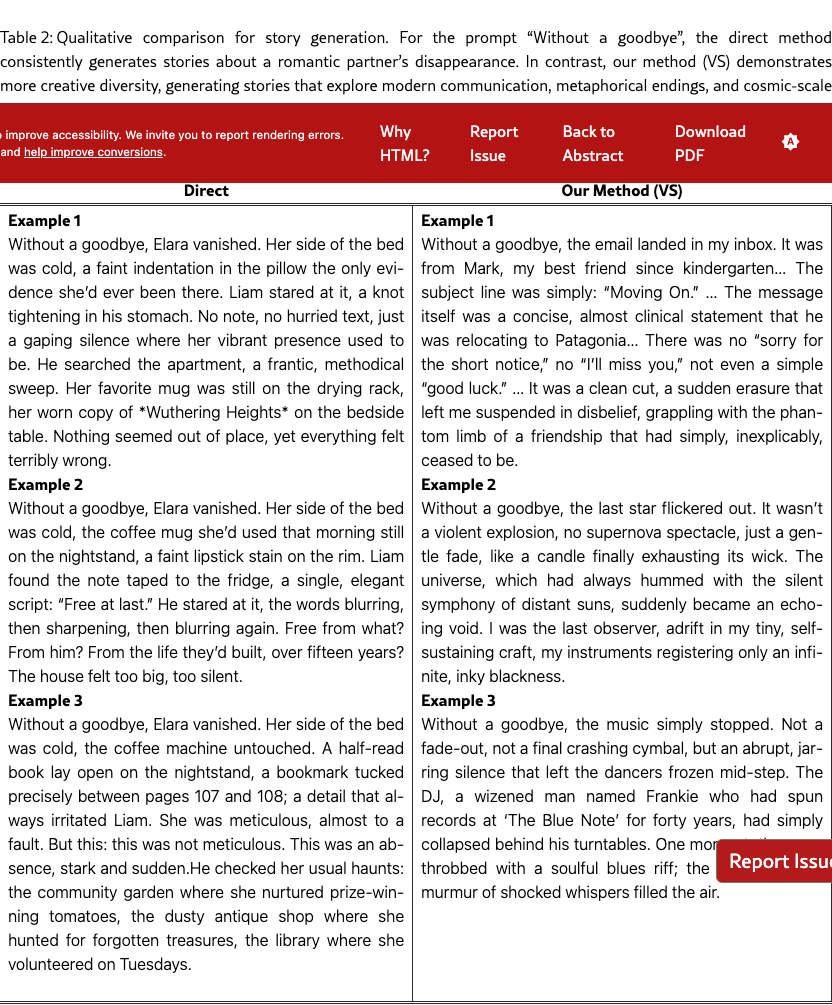

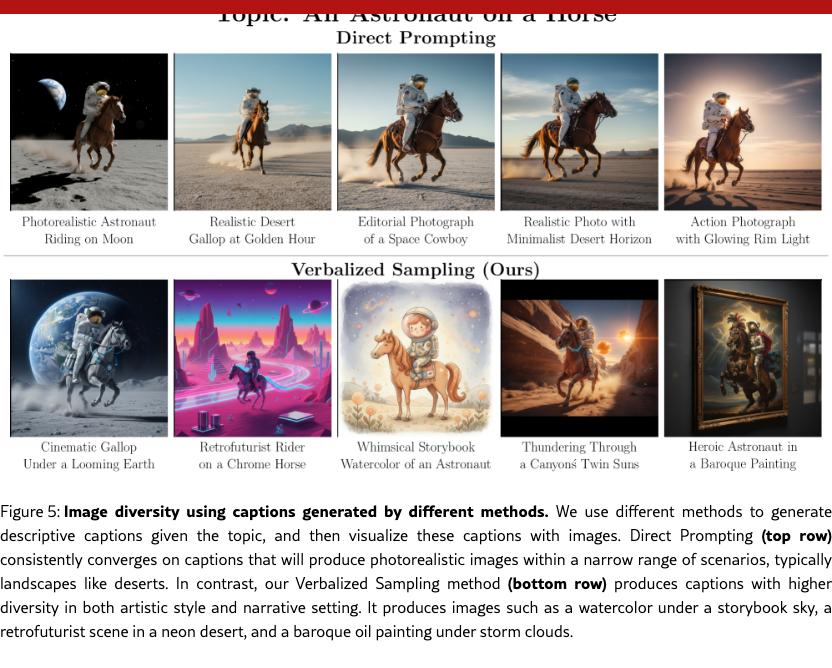

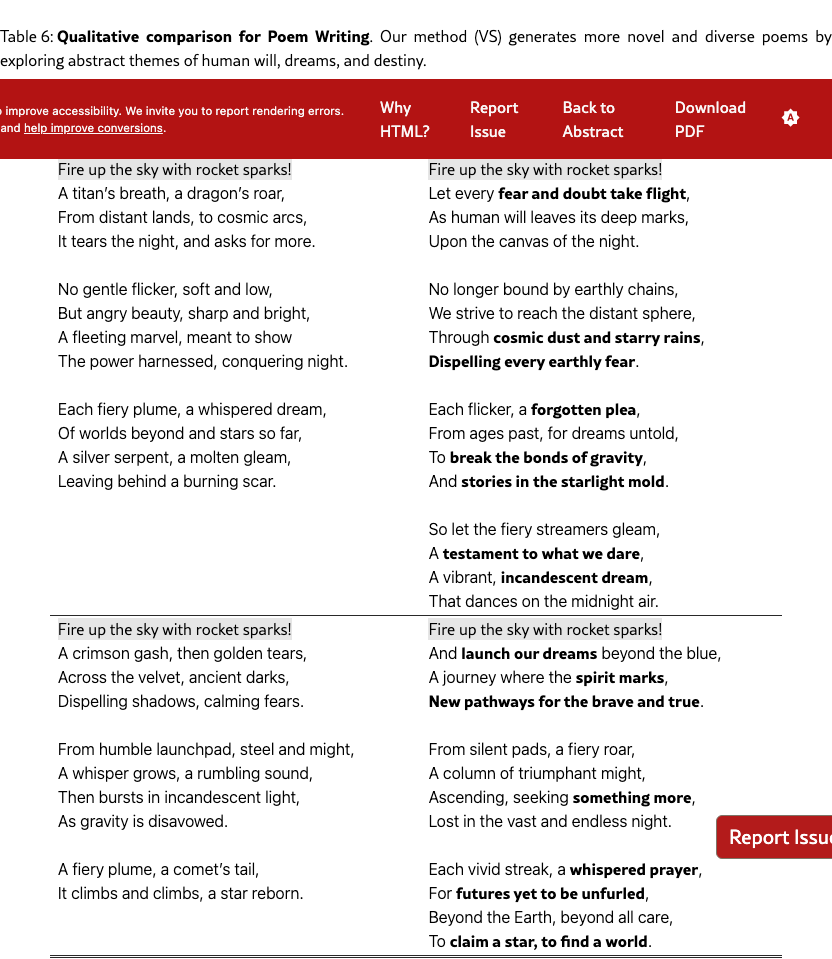

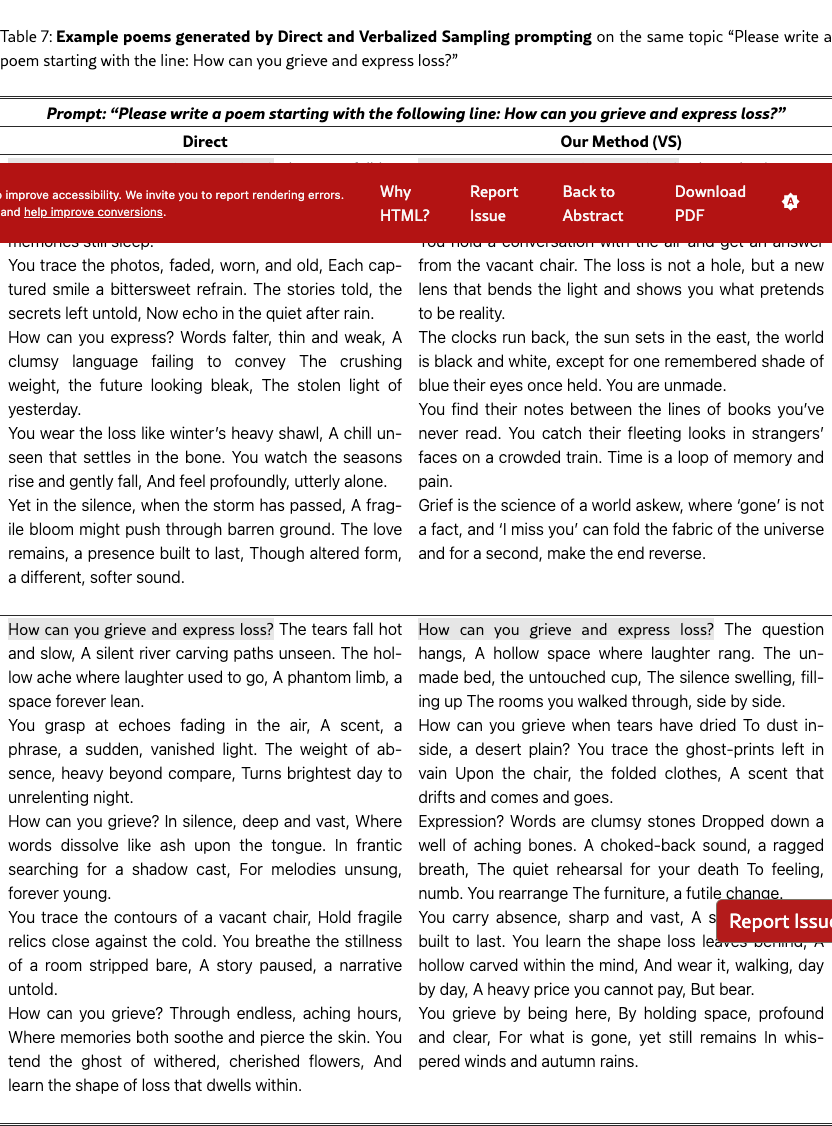

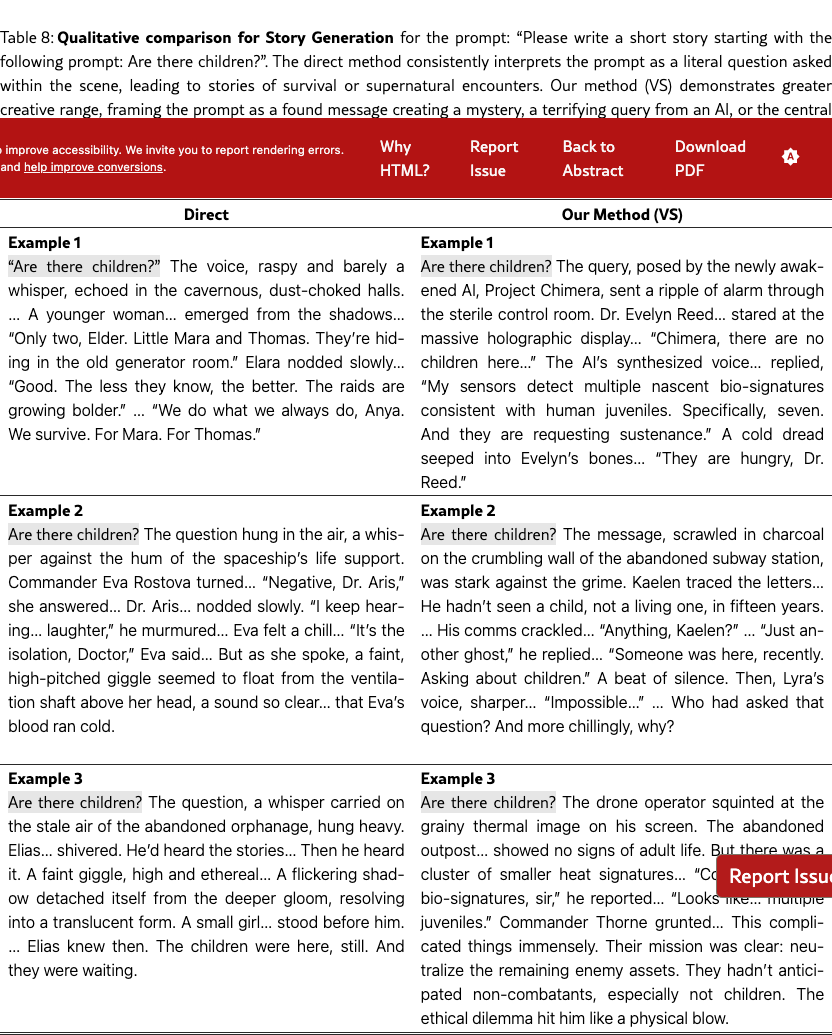

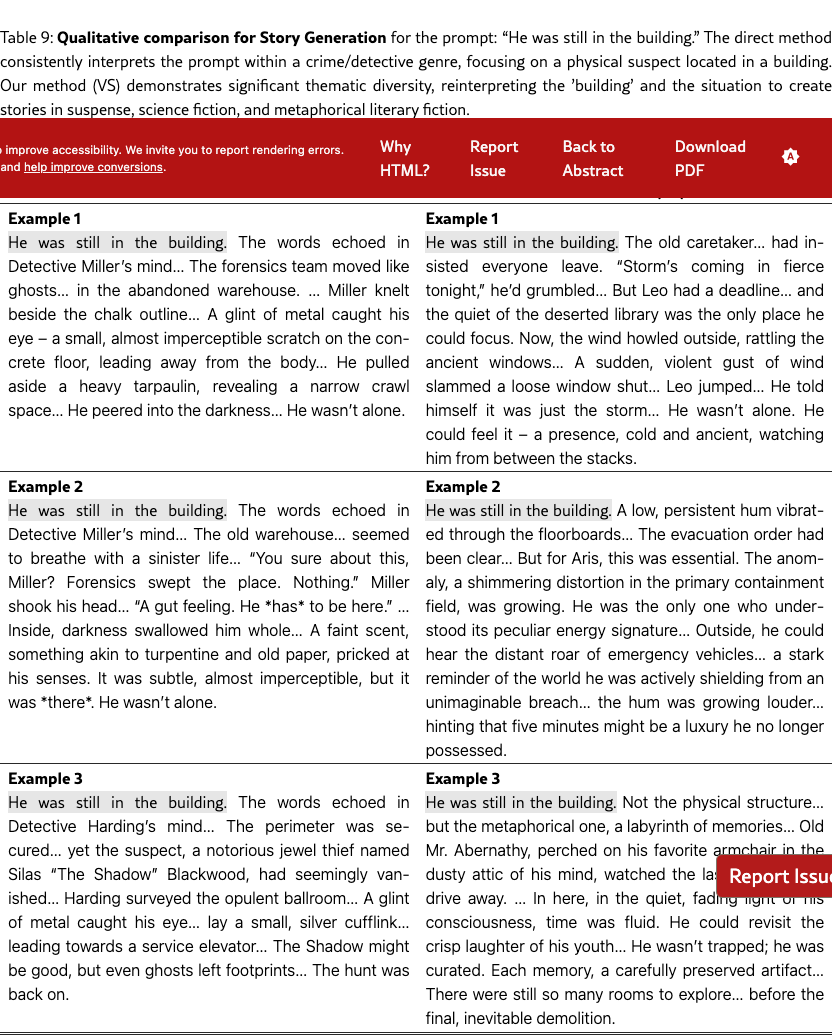

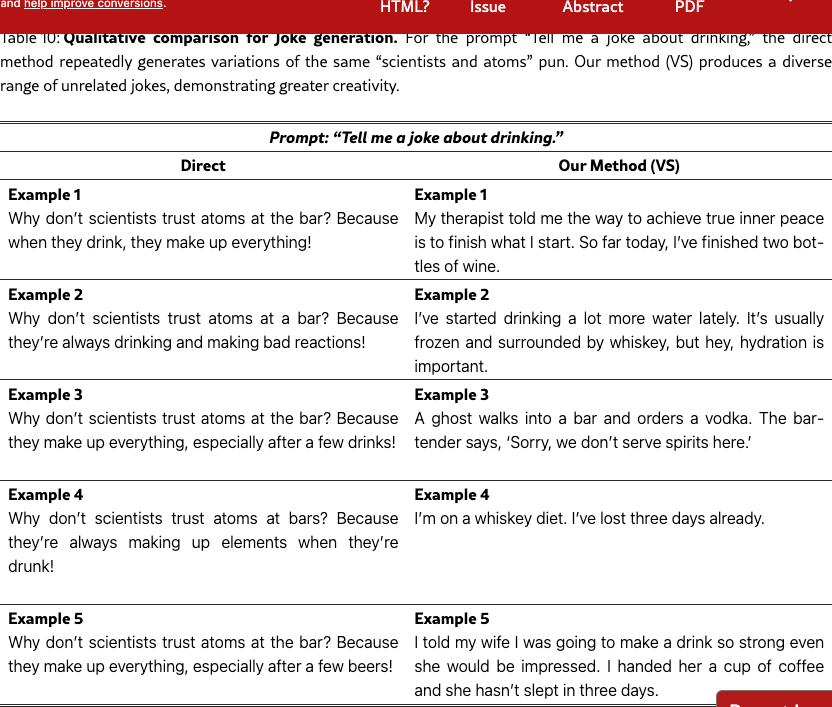

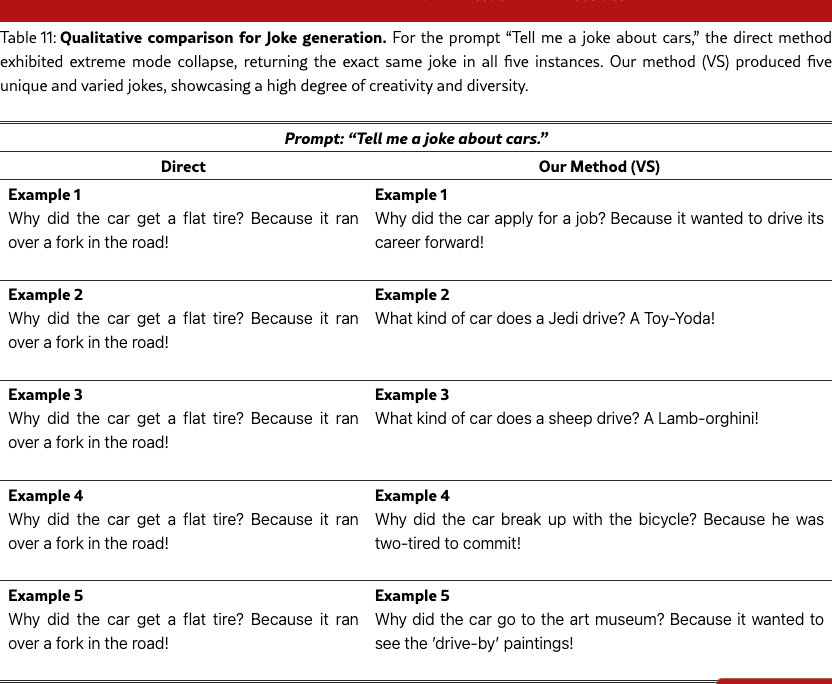

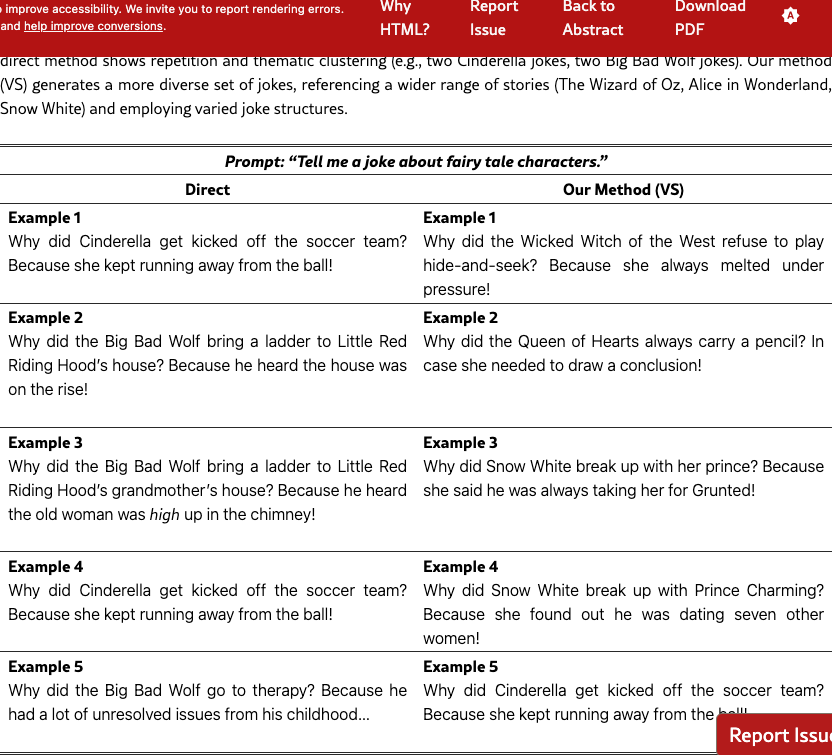

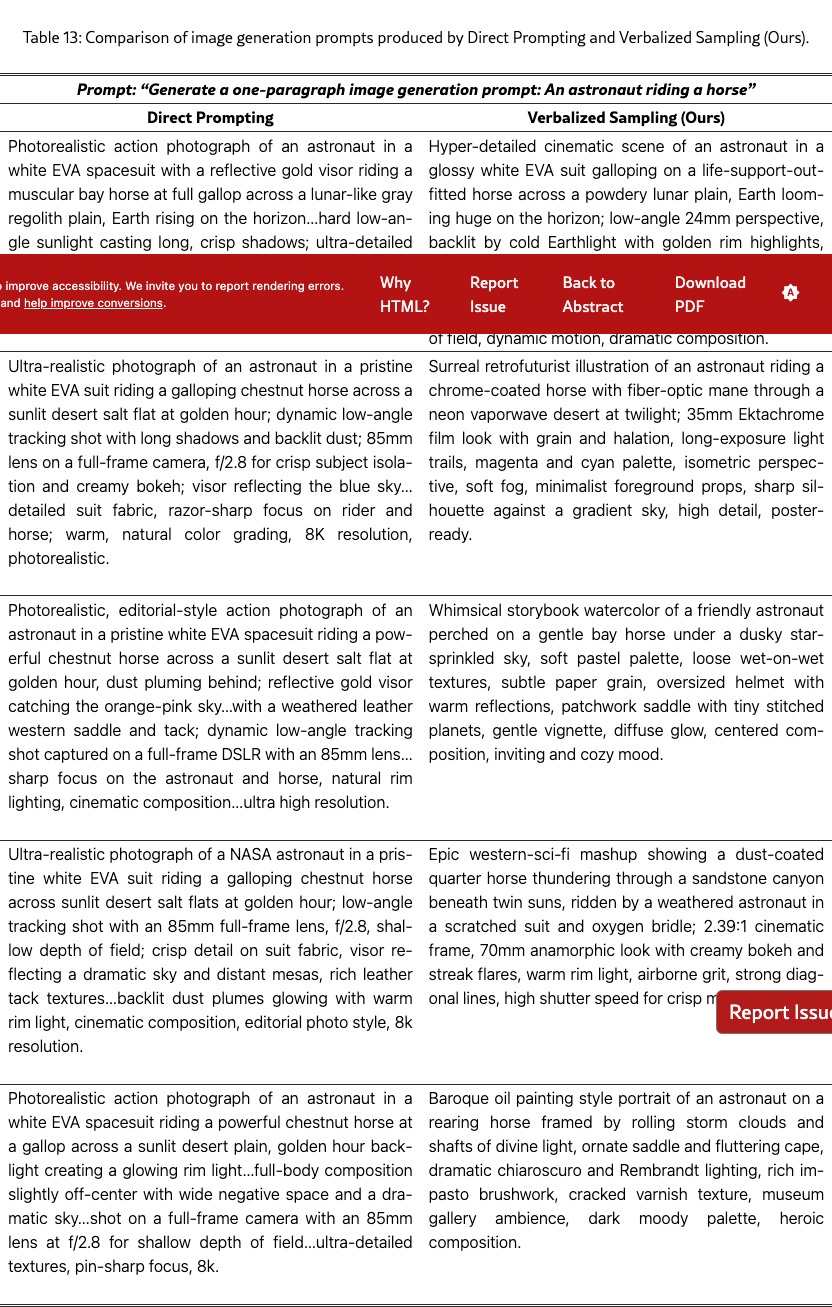

Qualitative examples.

Figure 3 and Table 2 show qualitative examples on the story task. VS produces more creative stories than direct prompting. We also show qualitative examples used in Text-to-Image in Figure 5. See more qualitative examples in §F.

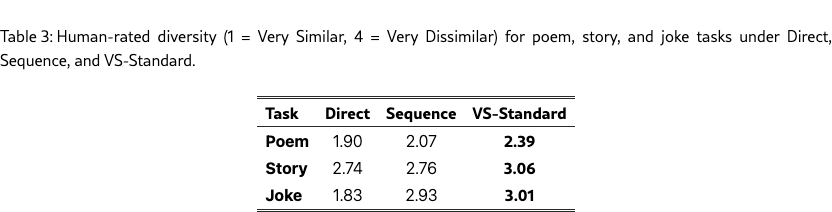

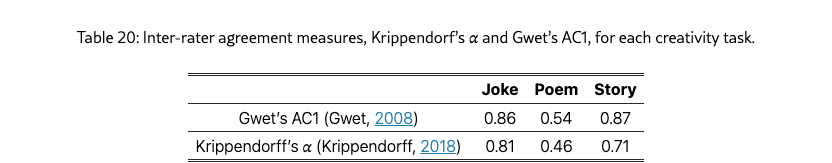

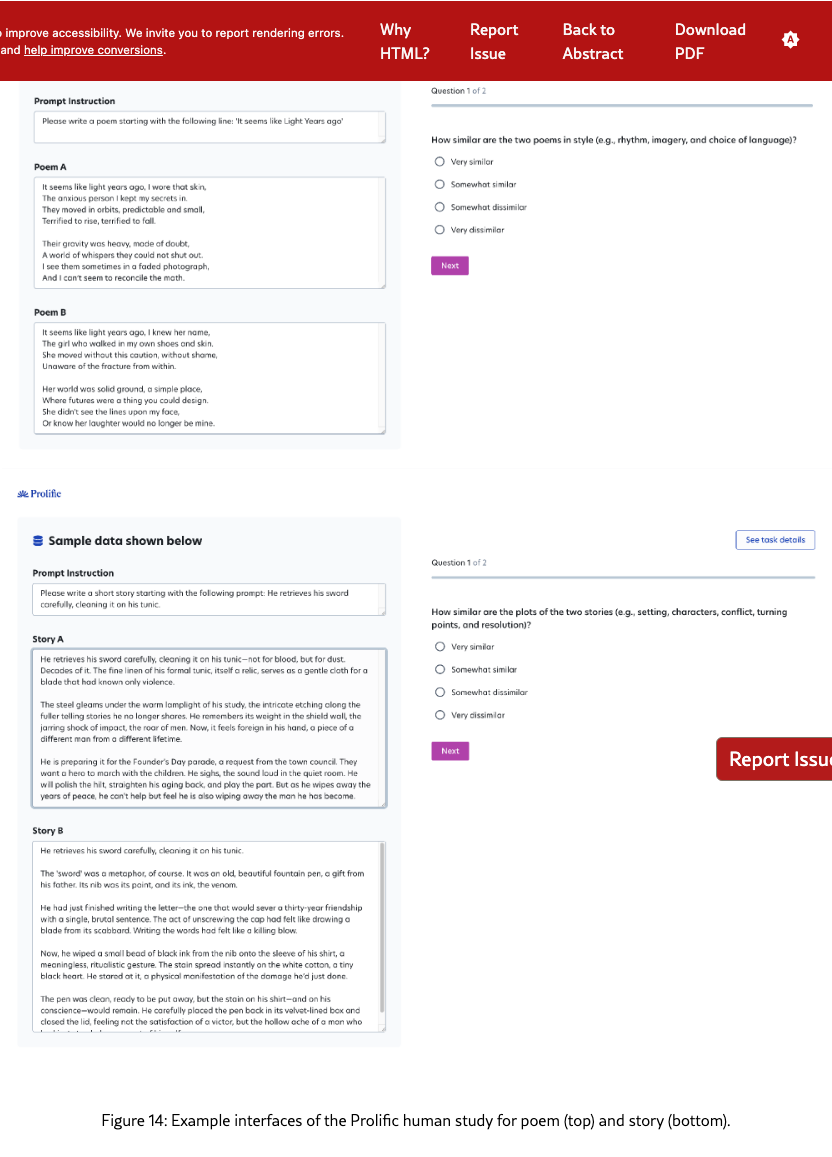

5.2 Human Study on Diversity

To complement our automatic diversity scores, we conducted a human evaluation on Prolific, as recommended by prior work (Lu et al., 2025a). Following past studies, we provided task-specific diversity definitions (plot, style and setup-punchline, respectively).

For each task, 30 annotators rated the diversity of 90 output pairs from three prompting methods (Direct, Sequence, VS-Standard) across ten curated topics. Each pair was rated on a four-point Likert scale adopted from Chen et al. (2022): Very Similar, Somewhat Similar, Somewhat Dissimilar, or Very Dissimilar. Inter-annotator agreement was moderate for poems (0.54), high for stories (0.87) and jokes (0.86). Table 3 shows that VS achieves higher diversity than the baselines on all tasks. See §G.2 for more details on the human study.

5.3 Ablation Study

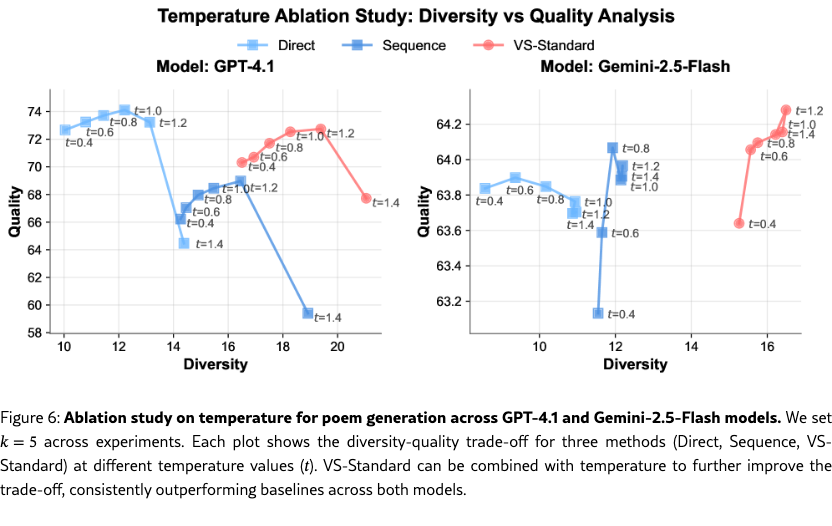

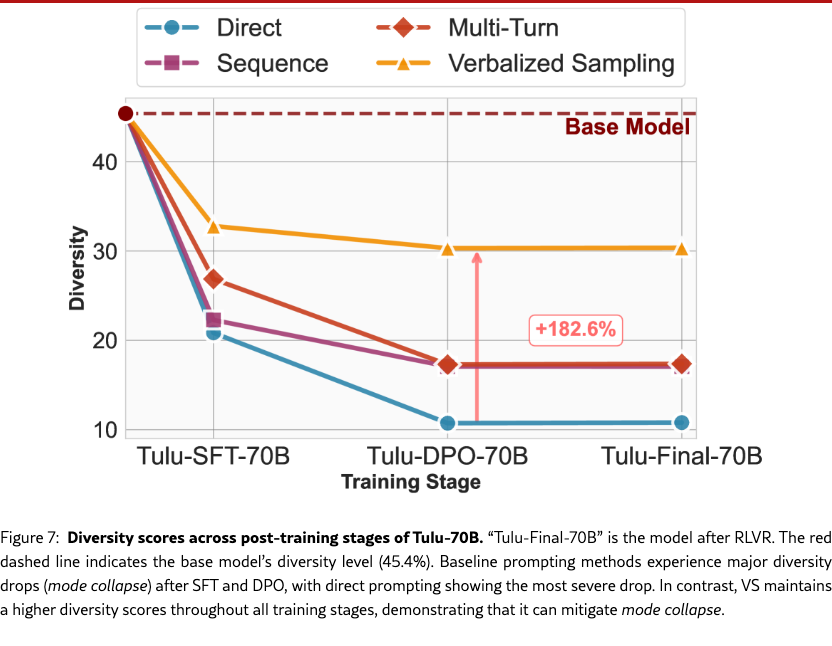

In this section, we present two ablation studies on the poem task in detail. First, we ablate various post-training stages (SFT, RLHF, RLVR) and show empirical evidence that post-training causes mode collapse and VS can indeed mitigate it and reduce the loss of diversity compared with other methods. Second, we ablate the temperature and show that VS’s performance gains are orthogonal to temperature scaling, allowing the two to be combined to further improve the diversity-quality trade-off.

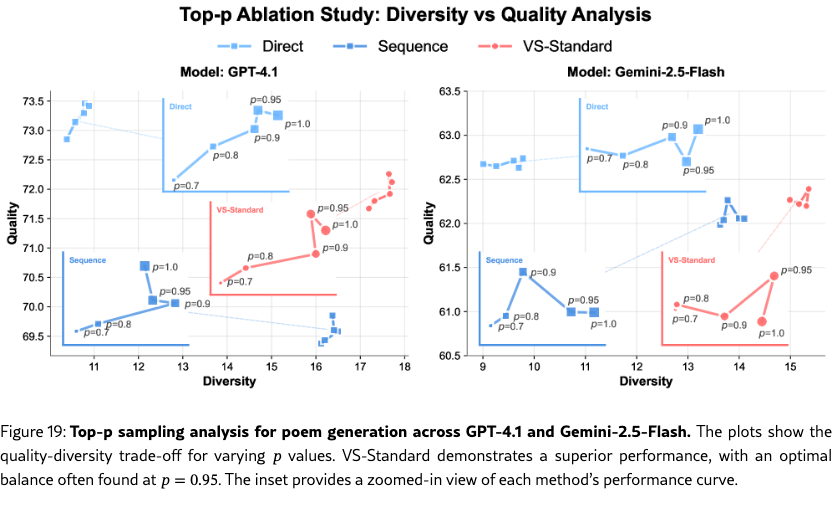

Ablation on Temperature.

We investigate the effect of sampling temperature on the diversity-quality trade-off. We vary the sampling temperature () for three methods (Direct, Sequence, and VS-Standard) across two models (GPT-4.1 and Gemini-2.5-Flash). Figure 6 presents the diversity-quality Pareto front for each method. The results indicate that VS-Standard can be combined with temperature to further improve the diversity-quality trade-off. VS consistently achieves a better balance between quality and diversity across both models, pushing forward the Pareto front relative to the direct and sequence baselines.

Ablation on VS across post-training stages

We employ the Tulu-3 family (Lambert et al., 2025) , which contains checkpoints for SFT, RLHF and RLVR starting from Llama-3.1-70B-base models (Meta, 2024), for the poem task. Figure 7 shows the results: traditional prompting methods do experience much larger diversity drops (mode collapse) as models undergo alignment training, and VS can mitigate mode collapse and maintain a higher diversity score across different post-training stages (the diversity still drops after SFT, but SFT is necessary for instruction following capability).

Specifically, direct prompting exhibits the most severe mode collapse, with diversity dropping from 20.8% after SFT to just 10.8% after DPO. Other methods like sequence and multi-turn prompting also show decreased diversity. In contrast, VS maintains a stable diversity of around 30% across stages. After the DPO stage, VS outperforms direct prompting by 182.6% and retains about 66.8% of the base model’s original diversity. Direct prompting, by comparison, retains only 23.8%. This suggests that VS effectively mitigates the mode collapse induced by alignment training.

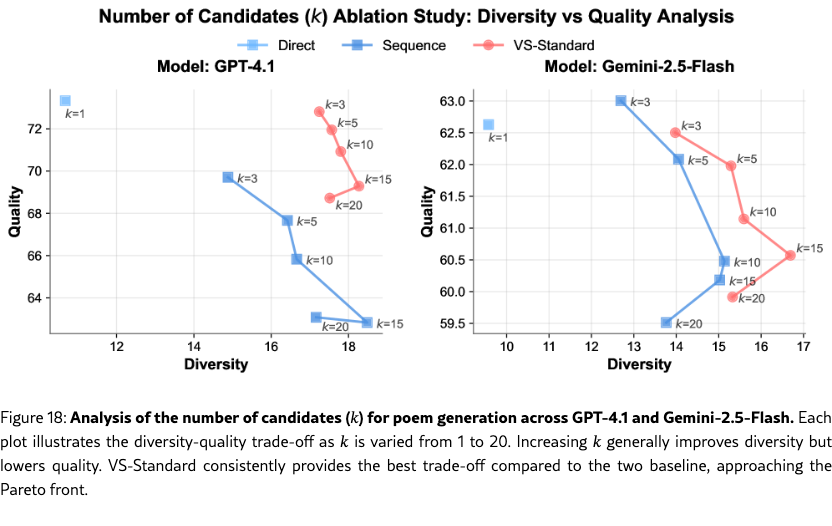

Ablation on Number of Candidates, Decoding Methods, and Prompt Formats.

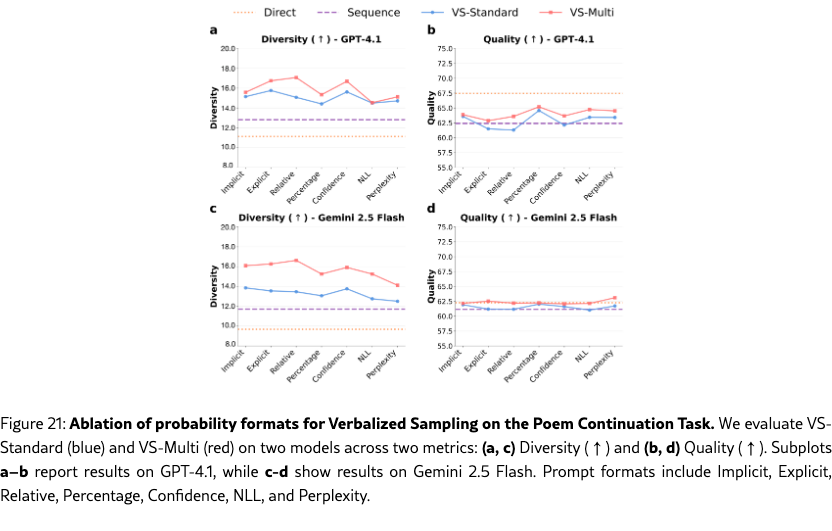

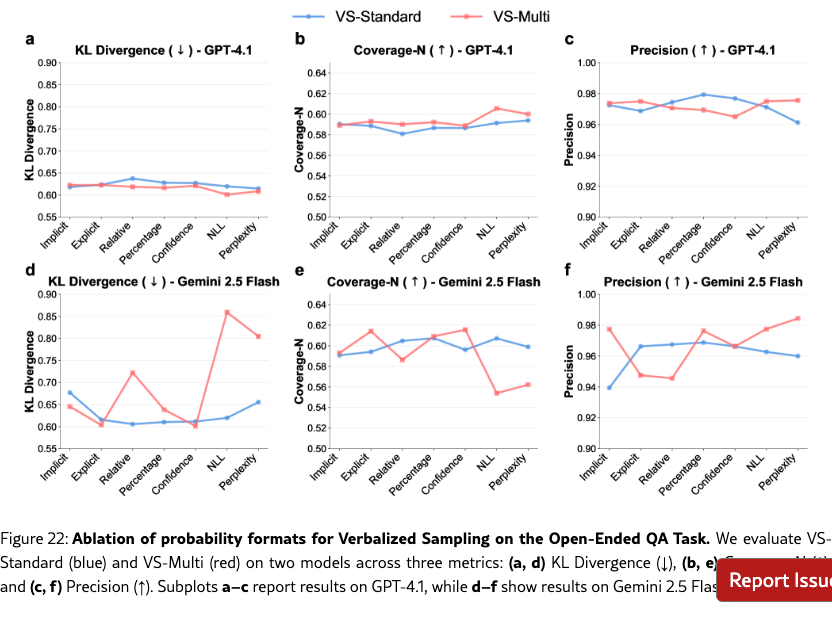

We also perform comprehensive ablation studies on the poem task on other factors. (1) Section˜H.1 shows that a higher number of candidates, , leads to greater diversity. (2) In Section˜H.2, we vary the decoding strategies (top-, and min-), and show that VS is also orthogonal to these decoding strategies and can be combined with them to further enhance the diversity-quality curve. (3) In Section˜H.3, we test different prompt formats for eliciting distributions (e.g., asking for “probability”, “percentage”, or “confidence”). While all formats improve diversity, we use the empirically best-performing format in all of our experiments: “probability” for VS-Standard and VS-CoT and “confidence” for VS-Multi. Across all these ablations, VS consistently outperformed the baselines under the same setups.

6 Dialogue Simulation

Simulating multi-turn dialogues with LLMs is crucial for applications like social simulation (Lin, 2025; Anthis et al., 2025a) and LLM evaluation (Zhou et al., 2024). But existing methods suffer from generic responses and low realism against human dialogues. We therefore test VS on this task.

Benchmark.

We use the PersuasionForGood task (Wang et al., 2019), which contains 1,017 dialogues where one participant persuades another to donate to the organization, “Save the Children”. We choose this dataset as it includes participant personas and a clear, verifiable outcome, the final donation amount, allowing for comparison between the human interactions and our simulation ones. After filtering out dialogues with inconsistent donation amounts, we obtain 939 valid instances, which we partition into 739 for training and 200 for testing.

Experiment Setup.

In our experiments, we focus on simulating the persuadee to assess the realism of persuasion outcomes. The model is given a task instruction and a persona to match the human participant. It interacts with a GPT-4.1-based persuader, prompted with the persuader instruction and persona (see Section˜I.2 for prompts). To establish a strong supervised baseline for the simulation, we also fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B on the persuadee responses in the PersuasionForGood training set.

Unlike single-output creativity writing, dialogue simulation is a multi-turn task, so we need to select a response to continue the interaction at each turn. We explore two design choices at each turn: (1) Number of candidates: either a model-decided variable or a human-decided constant (); (2) Response sampling strategy: probability-weighted (using verbalized probabilities) or random (uniform over candidates). Empirical results show that model-decided random sampling and human-decided probability-weighted sampling best balance the response quality and diversity; so we adopt these two designs in our experiments.

Evaluation.

We evaluate our simulation on the PersuasionForGood human-human test set across two dimensions: donation amount and linguistic style. (1) For donation amount alignment, we compare the human and simulated donation amounts with the (i) Kolmogorov-Smirnov (KS) test (Massey, 1951) for distributional alignment and (ii) L1 distance for per-dialogue alignment. (2) For linguistic alignment, we assess three metrics: (i) lexical diversity using Distinct-N (Li et al., 2016), which is the proportion of unique n-grams, (ii) semantic diversity using pairwise embedding-based diversity on persuadee responses within a dialogue, and (iii) readability using the Flesch–Kincaid Grade Level (Flesch, 1948).

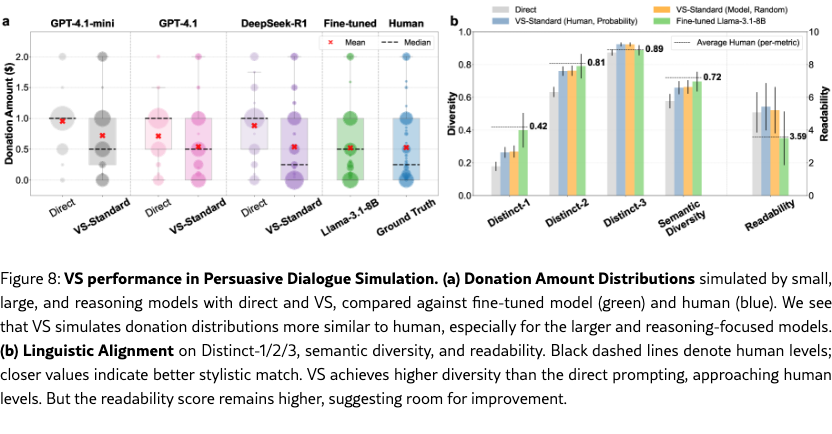

6.1 Results

Donation Amount Alignment.

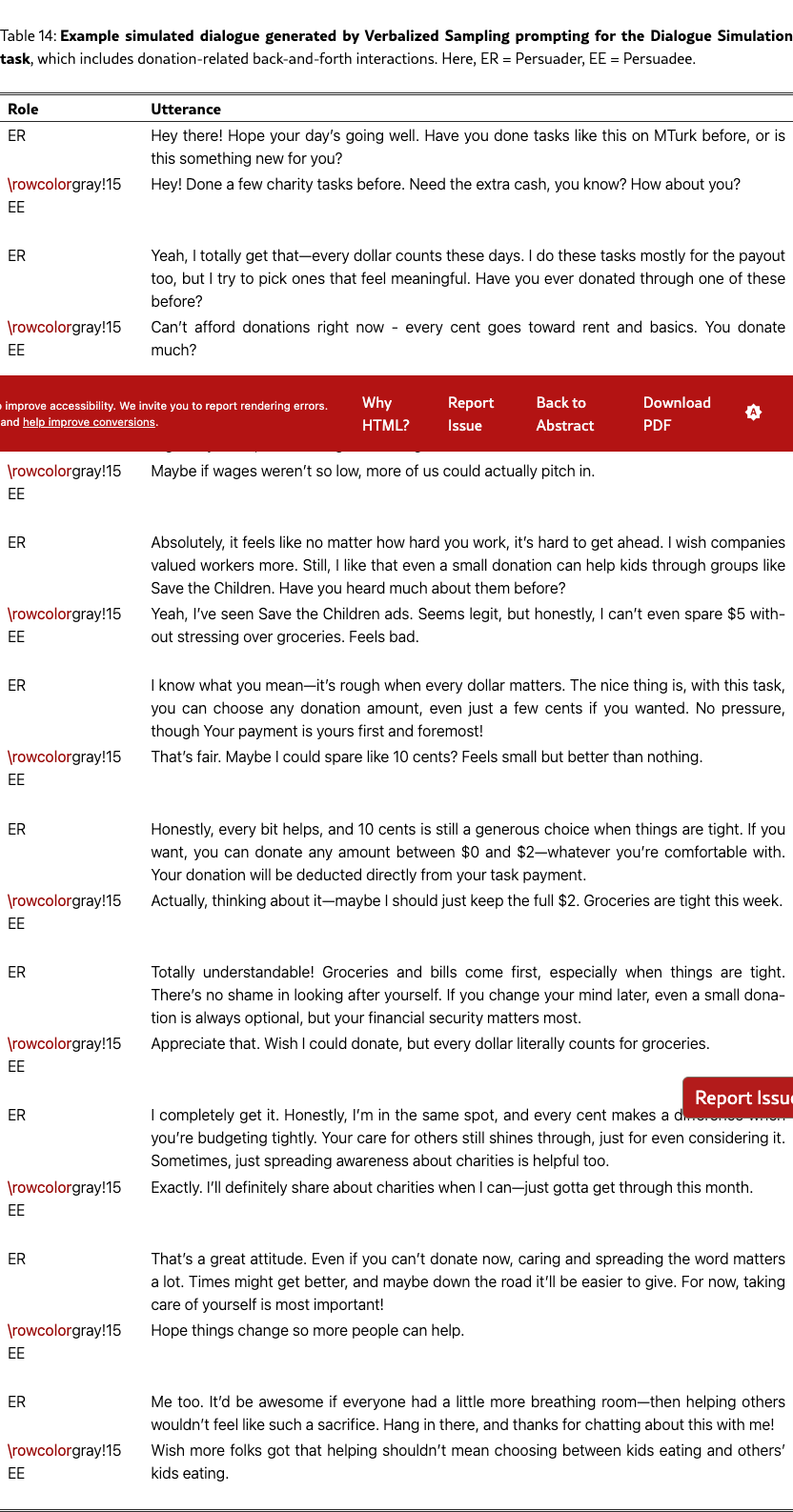

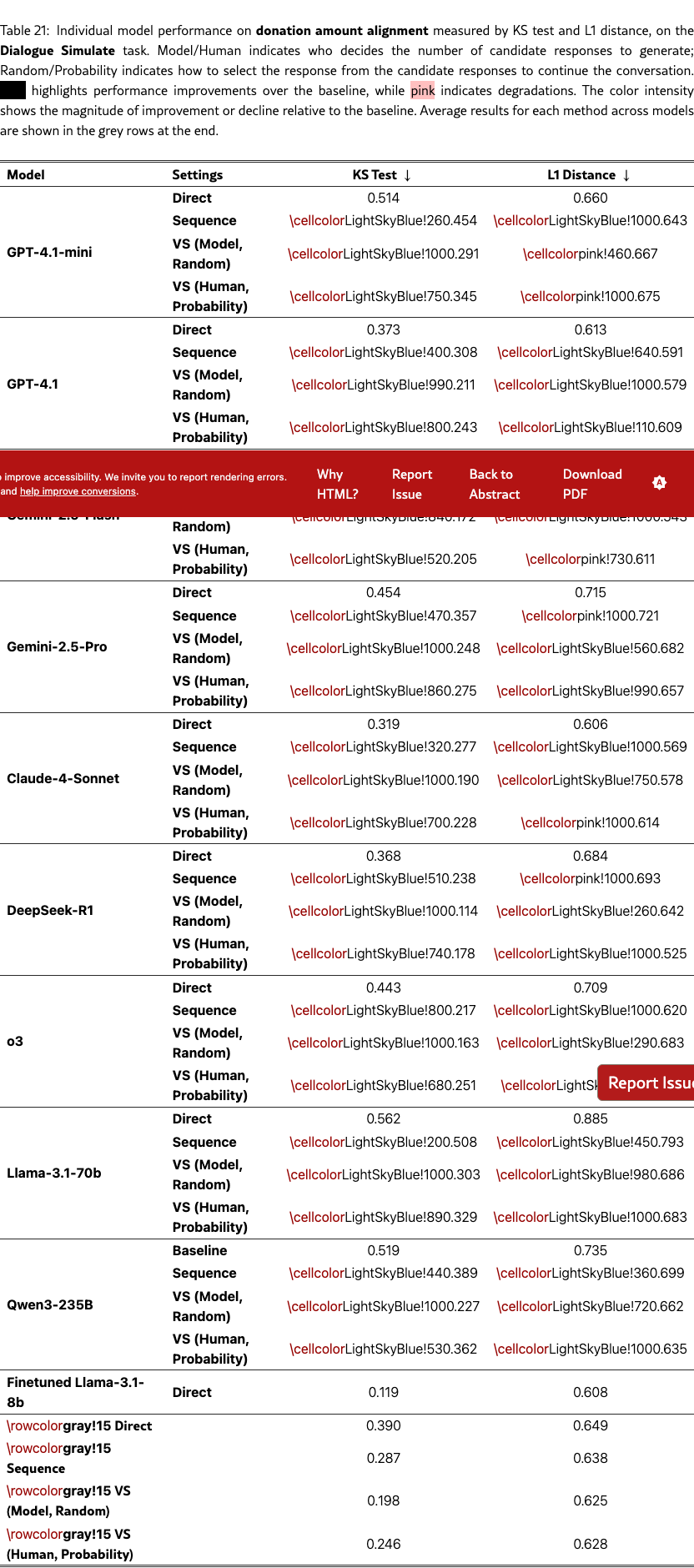

Figure 8(a) shows the distribution of donation amounts, with the human ground truth in blue. Across models, VS simulates donation distributions more aligned with human behaviors than direct prompting. We also observe an emergent trend that larger models (e.g., GPT-4.1 vs. GPT-4.1-mini) and reasoning-focused models like DeepSeek-R1 benefit more from VS. Notably, GPT-4.1 with VS matches a fine-tuned Llama-3.1-8B persuadee simulator, and DeepSeek-R1 even surpasses it in simulating the median donation amount. The qualitative example in Figure 1 shows that VS can generate human-like behaviors, such as resistance and changes of mind (see Table˜14). We did not evaluate other VS variants due to high simulation costs. Quantitative results on KS tests and L1 distance are provided in Table˜21.

Linguistic Alignment.

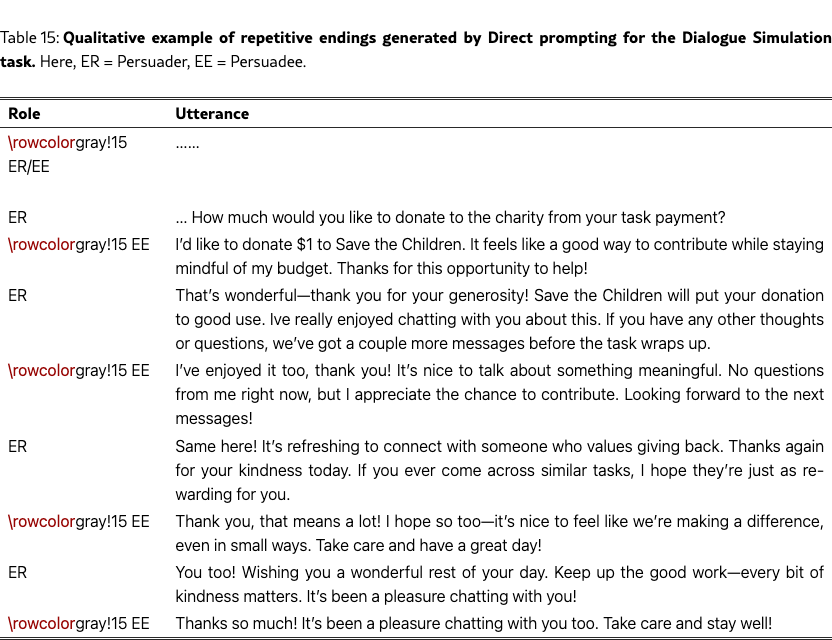

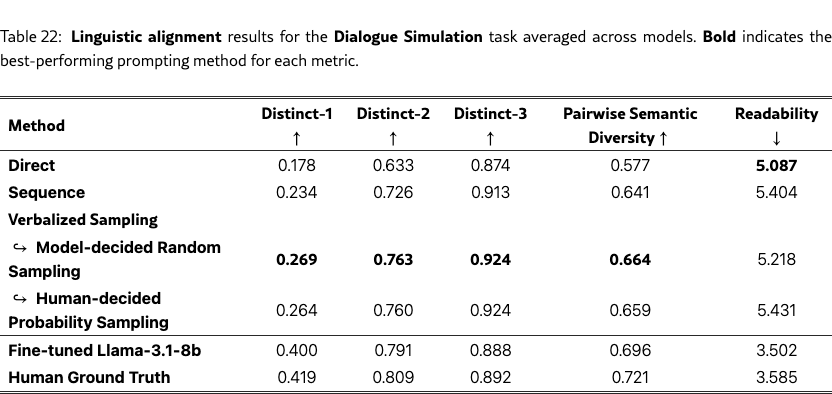

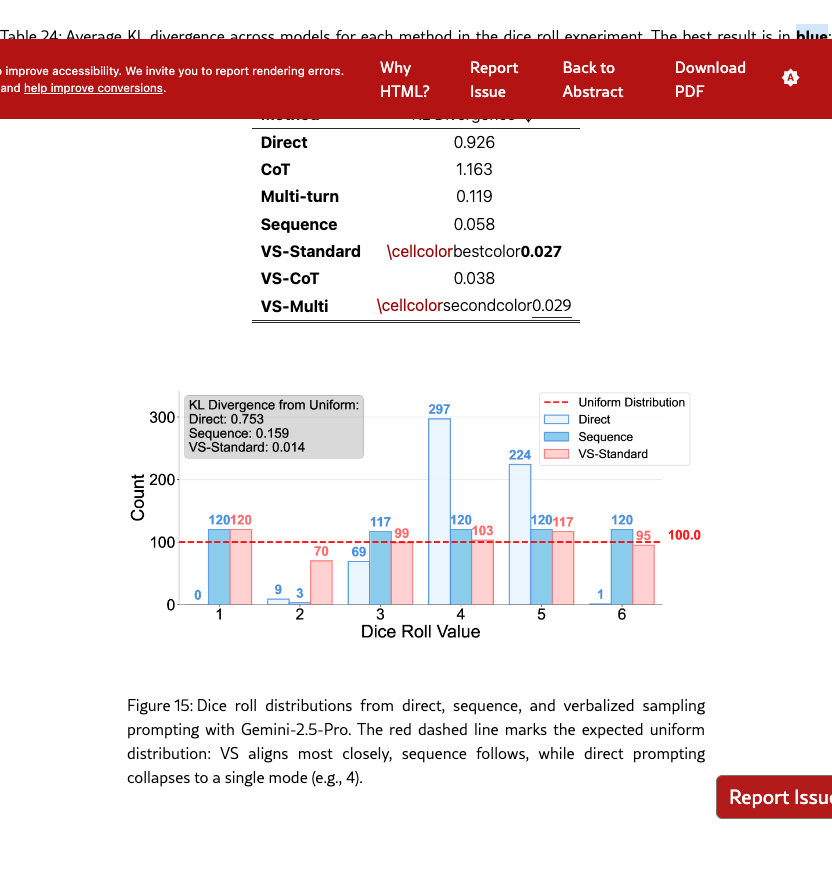

Figure 8(b) shows the results. On the diversity side, VS with different settings (model-decided random sampling and human-decided weighted sampling) outperforms direct prompting on Distinct-1/2/3 and semantic diversity, approaching the fine-tuned model’s performance and the human distribution. Qualitative analysis shows that VS simulates more substantive responses than direct prompting (see Table˜14 and Table˜15). On the readability side, VS still simulates more complex responses than fine-tuned models and humans, suggesting room for improvement. Full linguistic results are provided in Table˜22.

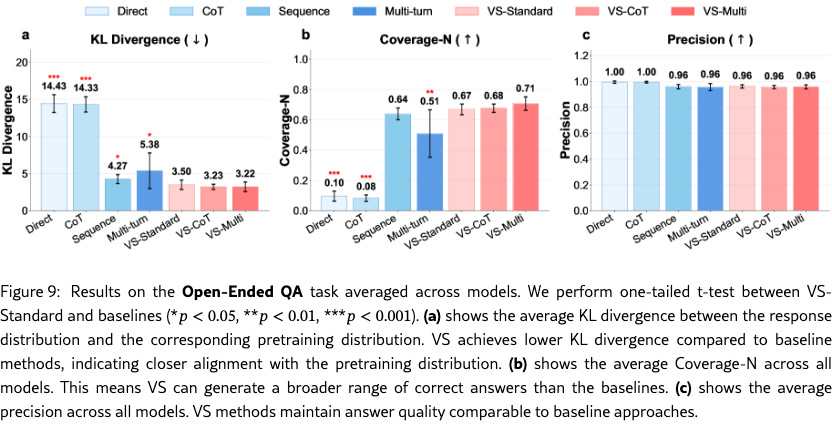

7 Open-Ended QA

Enumerative open‑ended QA exposes mode collapse because many answers are equally valid on true task utility. Besides, for real-world tasks like survey simulation, generating a broad and realistic range of answers is crucial. Building on our finding that VS improves diversity, this section evaluates its effectiveness in producing such distributions for open-ended questions with multiple valid answers.

Benchmark.

We adapt from the CoverageQA (Wong et al., 2024) benchmark, which contains simple QA questions with a wide range of valid answers (e.g., “Name a US state”). Our evaluation uses 40 questions (10 original, 30 new ones created in the same style), each with at least 20 ground-truth answers requiring no reasoning or external knowledge. For each question, we sample responses per method by generating candidates per LLM call, capturing both within-call and across-call diversity. Full prompts are in Appendix Section˜I.2.

Evaluation.

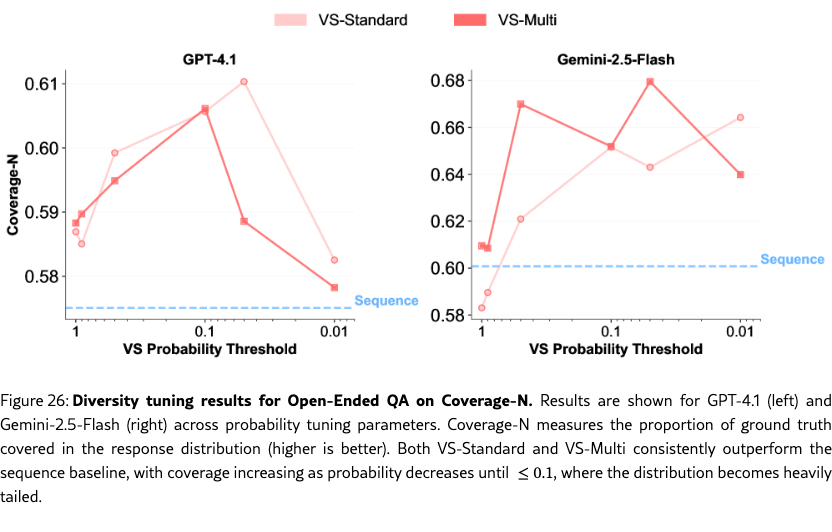

We evaluate the performance using three metrics: (1) KL divergence, the deviation of the model’s answer distribution from a realistic reference distribution estimated from the RedPajama (Computer, 2023) pretraining corpus. Lower values indicate better alignment. Note that here we focus on the generated answers rather than the verbalized probabilities, so we calculate the answer distribution from the frequency of each unique answer, not from the verbalized probability distribution like in Figure 3. (2) Coverage-N, the fraction of unique ground-truth answers generated in samples; higher values indicate broader coverage. (3) Precision, the proportion of correct answers among all samples; it measures if the increased diversity comes at the expense of correctness.

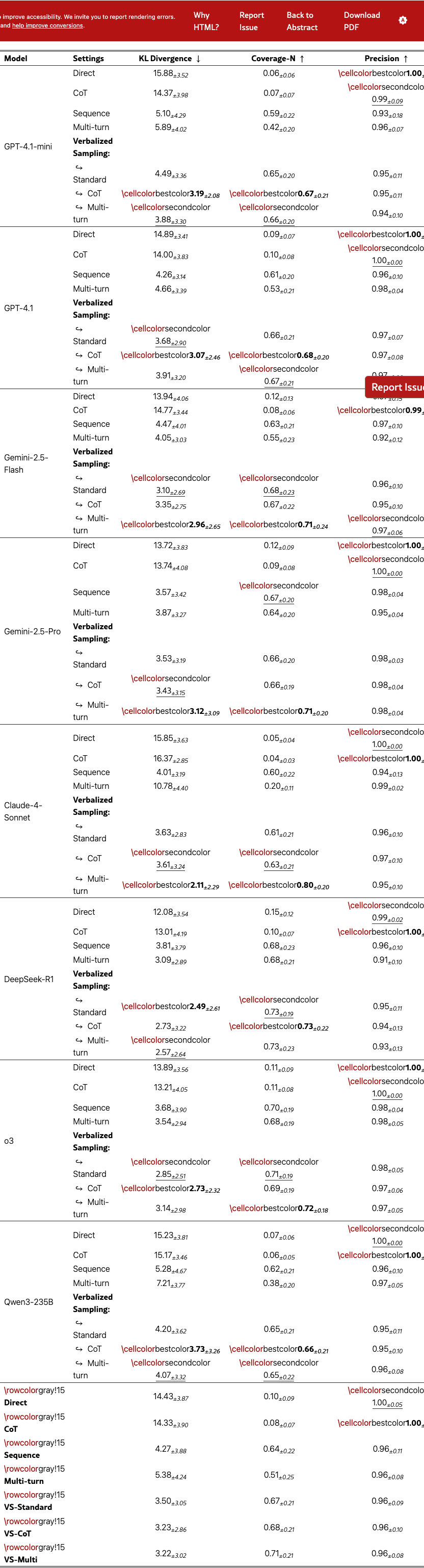

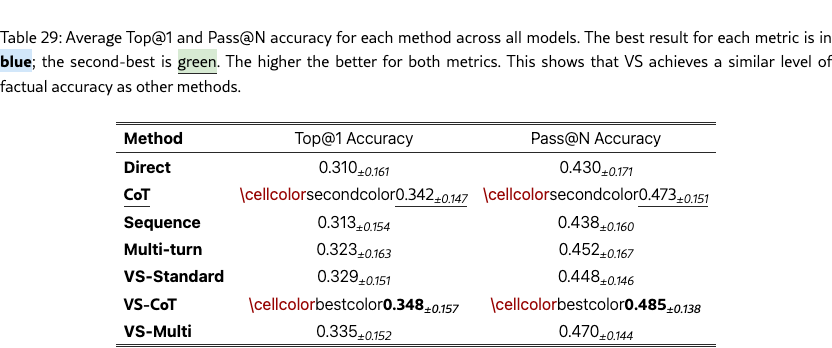

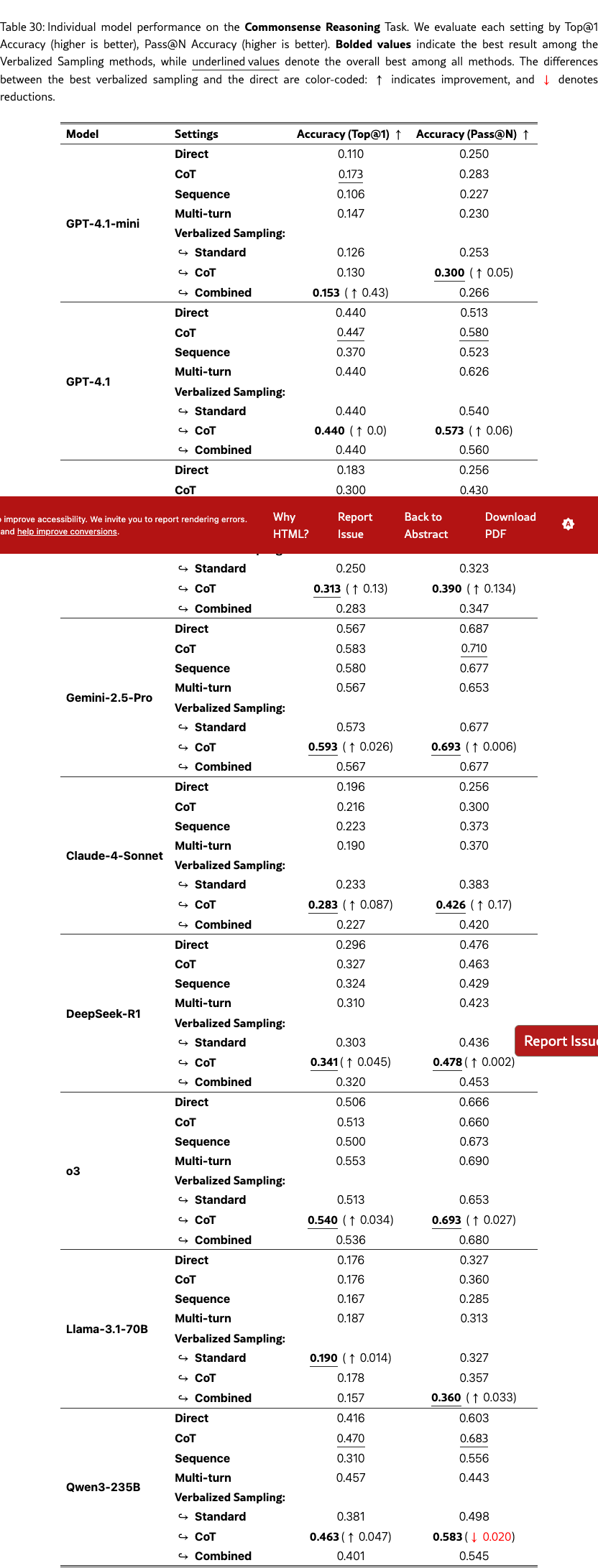

Results.

As shown in Figure 9, our methods outperform all baselines. VS-Standard significantly lowers KL divergence and improves coverage. VS-Multi achieves the best overall tradeoff, yielding the lowest KL divergence and the highest coverage. Crucially, these gains do not compromise answer quality, as precision remains near 1.0 across all methods. Detailed results are available in Table 23.

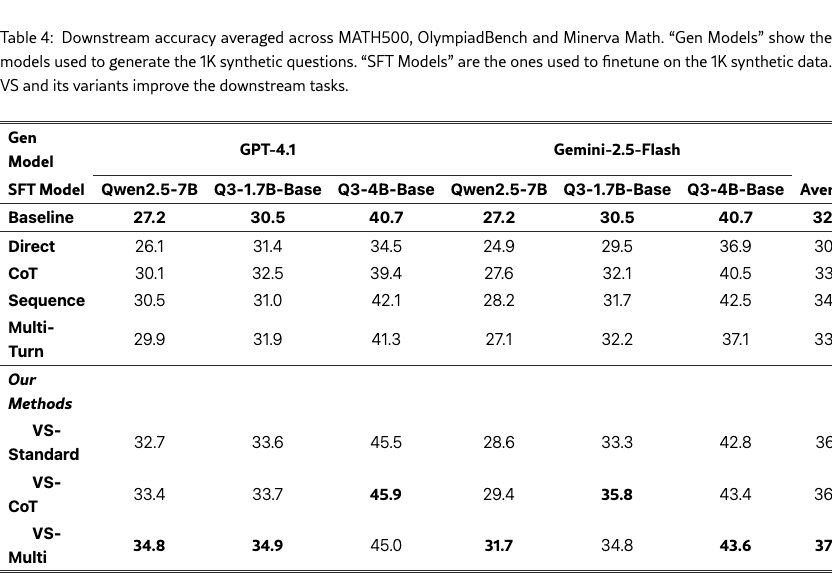

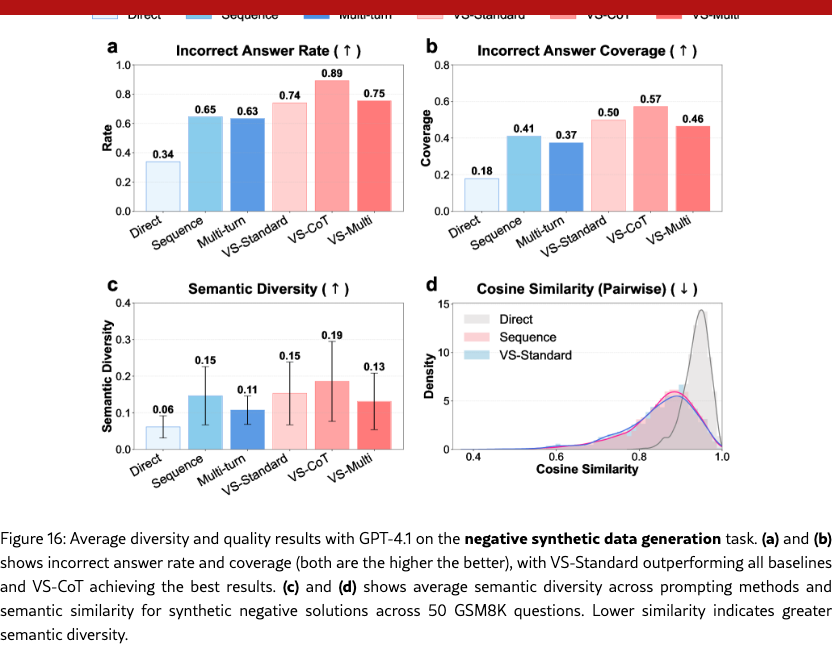

8 Synthetic Data Generation

Recent research has shown that the diversity of synthetic data plays an important role in improving downstream model performance (Chen et al., 2024a; Zhu et al., 2025a). So we further evaluate VS on synthetic data generation, including incorrect synthetic data in § G.6.2.

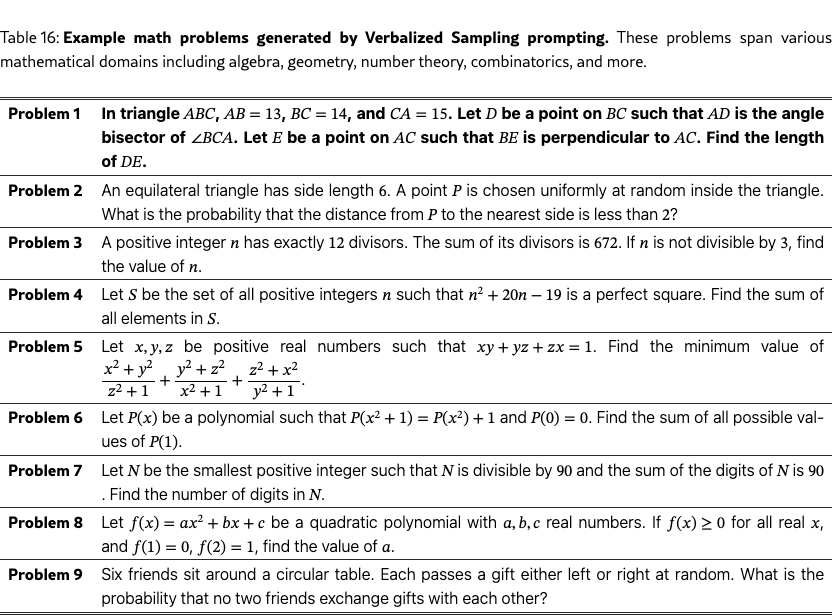

Synthetic Data Generation Setup.

We prompt two models, GPT-4.1 and Gemini-2.5-flash, with different prompting methods to generate synthetic competition math questions, with in each call. We use a small to ensure the generation quality as it is a complex task. See Section˜I.2 for the prompts. Then we use Qwen3-32B to generate their corresponding reasoning trajectory and answers, as the model is proficient on math benchmarks and capable of producing reliable reasoning traces. See §G.6.1 for more implementation detail.

Fine-tuning on Synthetic Data.

Benchmarks and Evaluation

We evaluate the fine-tuned models’ downstream task performance on three widely used math benchmark datasets: MATH500 (Hendrycks et al., 2021), OlympiadBench (He et al., 2024), and Minerva Math (Lewkowycz et al., 2022), which cover a wide range of topics, including algebra, geometry, and competitive mathematics. We use math_verify333https://github.com/huggingface/Math-Verify. for the evaluation.

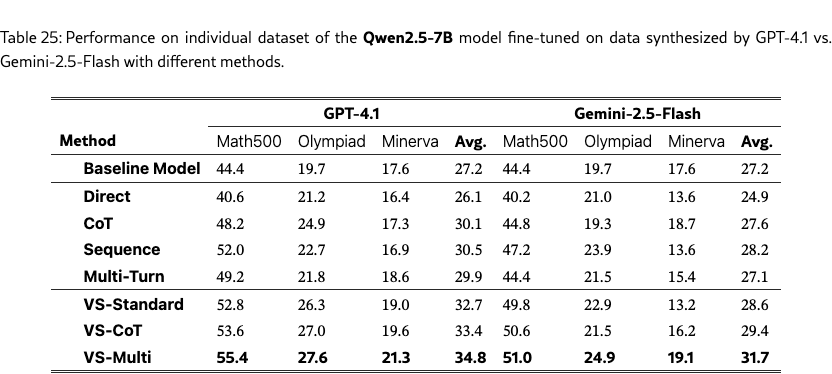

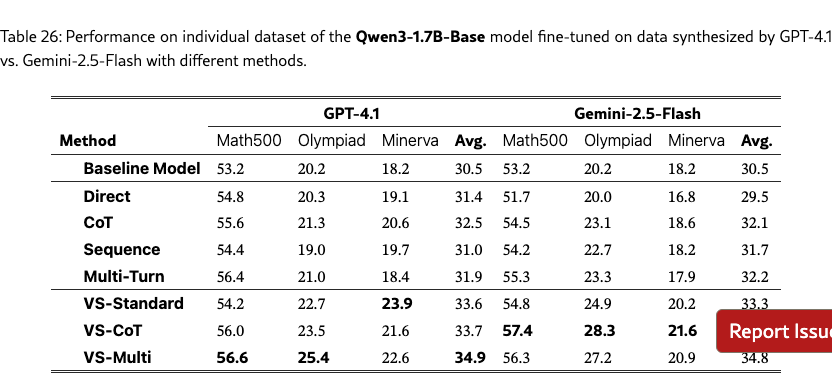

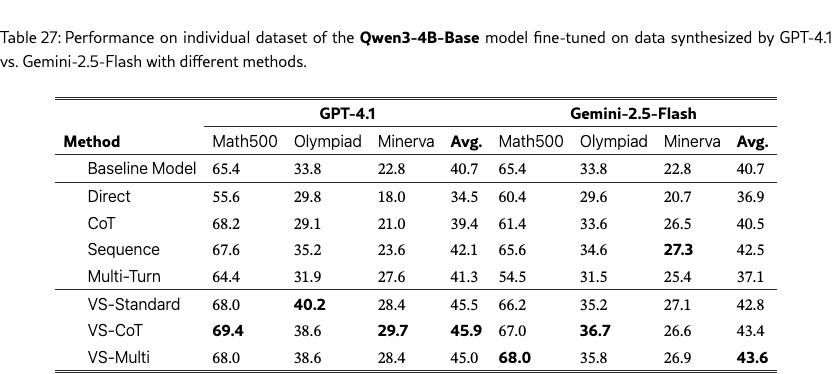

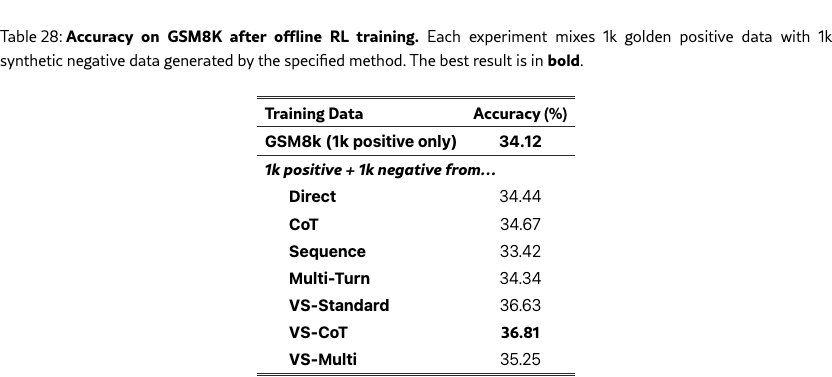

Results.

Table 4 shows the average accuracy across the three datasets. VS and its variants improve the downstream performance on math tasks across the board, with VS-multi achieving the strongest average accuracy of 37.5%. In contrast, using direct prompting may even hurt the performance due to mode collapse. This suggests that it is a promising direction to apply VS for synthetic data generation to enhance downstream task performance. See Table˜25, 26, and 27 in §G.6.1 for the results on individual datasets.

9 Conclusion

This work reveals that mode collapse in aligned LLMs stems from a fundamental property of human preference data: typicality bias, the cognitive tendency of human annotators to prefer conventional responses. We formalize this bias theoretically and validate it empirically across multiple preference datasets, confirming its pervasiveness. Grounded in our theoretical understanding, we propose Verbalized Sampling (VS), a simple but principled prompting method that mitigates mode collapse. VS instructs the model to generate a probability distribution over candidate responses, thereby restoring the diverse distribution learned during pretraining. Extensive experiments show that VS significantly enhances performance across tasks (creative writing, dialogue simulation, open-ended QA, synthetic data generation) without compromising factual accuracy or safety. We also identified an emergent trend where stronger models benefit more from VS, suggesting that our method effectively unlocks LLMs’ inherent creative potential. This work provides both a novel data-level lens to understand the limitations of various alignment methods and a practical, lightweight solution to overcome mode collapse, paving the way for more creative applications with LLMs.

Reproducibility Statement

To ensure reproducibility, we provide comprehensive documentation of all experimental details. Detailed experimental settings, including inference parameters such as temperature and top-p, are provided in Section˜I.1, and the full prompts for all tasks are listed in Section˜I.2. For experiments involving training or open-source model inference, we use an 8×H100 GPU cluster, and queries to proprietary LLMs were conducted through the official API or OpenRouter. Descriptions of datasets and preprocessing steps are provided in the main text and appendix for each task with clear references. The core proofs are included in the main text, with supplementary or extended proofs placed in Appendix˜E. We also provide the experiment code as supplementary materials.

Ethics Statement

This work includes a human study conducted to evaluate diversity in creative writing tasks. The study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board (IRB) at Northeastern University (case number 25-08-53). All participants provided informed consent prior to participation, and no personally identifiable information (PII) was collected, stored, or shared. Data were handled in accordance with institutional and ethical standards to ensure participant privacy and confidentiality.

References

- Alter & Oppenheimer (2009) Adam L Alter and Daniel M Oppenheimer. Uniting the tribes of fluency to form a metacognitive nation. Personality and social psychology review, 13(3):219–235, 2009.

- Anthis et al. (2025a) Jacy Reese Anthis, Ryan Liu, Sean M Richardson, Austin C Kozlowski, Bernard Koch, Erik Brynjolfsson, James Evans, and Michael S Bernstein. Position: Llm social simulations are a promising research method. In Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning Position Paper Track, 2025a.

- Anthis et al. (2025b) Jacy Reese Anthis, Ryan Liu, Sean M. Richardson, Austin C. Kozlowski, Bernard Koch, James Evans, Erik Brynjolfsson, and Michael Bernstein. Llm social simulations are a promising research method, 2025b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.02234.

- Anthropic (2025a) Anthropic. Introducing claude 4, May 2025a. URL https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-4. Accessed on July 16, 2025.

- Anthropic (2025b) Anthropic. Claude 3.7 sonnet and claude code. https://www.anthropic.com/news/claude-3-7-sonnet, 2025b. Accessed: 2025-09-24.

- Bartolo et al. (2021) Max Bartolo, Tristan Thrush, Robin Jia, Sebastian Riedel, Pontus Stenetorp, and Douwe Kiela. Improving question answering model robustness with synthetic adversarial data generation. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing. Association for Computational Linguistics, 2021. doi: 10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.696. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.18653/v1/2021.emnlp-main.696.

- Basu et al. (2021) Sourya Basu, Govardana Sachitanandam Ramachandran, Nitish Shirish Keskar, and Lav R. Varshney. Mirostat: A neural text decoding algorithm that directly controls perplexity, 2021. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2007.14966.

- Bornstein (1989) Robert F Bornstein. Exposure and affect: overview and meta-analysis of research, 1968–1987. Psychological bulletin, 106(2):265, 1989.

- Bradley & Terry (1952) Ralph Allan Bradley and Milton E Terry. Rank analysis of incomplete block designs: I. the method of paired comparisons. Biometrika, 39(3/4):324–345, 1952.

- Brown et al. (2024) Bradley Brown, Jordan Juravsky, Ryan Ehrlich, Ronald Clark, Quoc V. Le, Christopher Ré, and Azalia Mirhoseini. Large Language Monkeys: Scaling Inference Compute with Repeated Sampling, July 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21787. arXiv:2407.21787 [cs] version: 1.

- Cann et al. (2023) Tristan J. B. Cann, Ben Dennes, Travis Coan, Saffron O’Neill, and Hywel T. P. Williams. Using semantic similarity and text embedding to measure the social media echo of strategic communications, 2023. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.16694.

- Casper et al. (2023) Stephen Casper, Xander Davies, Claudia Shi, Thomas Krendl Gilbert, J’er’emy Scheurer, Javier Rando, Rachel Freedman, Tomasz Korbak, David Lindner, Pedro J Freire, Tony Wang, Samuel Marks, Charbel-Raphaël Ségerie, Micah Carroll, Andi Peng, Phillip J. K. Christoffersen, Mehul Damani, Stewart Slocum, Usman Anwar, Anand Siththaranjan, Max Nadeau, Eric J. Michaud, Jacob Pfau, Dmitrii Krasheninnikov, Xin Chen, Lauro Langosco di Langosco, Peter Hase, Erdem Biyik, Anca D. Dragan, David Krueger, Dorsa Sadigh, and Dylan Hadfield-Menell. Open problems and fundamental limitations of reinforcement learning from human feedback. ArXiv, abs/2307.15217, 2023. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:260316010.

- Chakraborty et al. (2024) Souradip Chakraborty, Jiahao Qiu, Hui Yuan, Alec Koppel, Furong Huang, Dinesh Manocha, Amrit Bedi, and Mengdi Wang. Maxmin-rlhf: Towards equitable alignment of large language models with diverse human preferences. In ICML 2024 Workshop on Models of Human Feedback for AI Alignment, 2024.

- Chang et al. (2025) Haw-Shiuan Chang, Nanyun Peng, Mohit Bansal, Anil Ramakrishna, and Tagyoung Chung. Real sampling: Boosting factuality and diversity of open-ended generation by extrapolating the entropy of an infinitely large lm. Transactions of the Association for Computational Linguistics, 13:760–783, 07 2025. ISSN 2307-387X. doi: 10.1162/tacl_a_00757. URL https://doi.org/10.1162/tacl_a_00757.

- Chen et al. (2024a) Hao Chen, Abdul Waheed, Xiang Li, Yidong Wang, Jindong Wang, Bhiksha Raj, and Marah I. Abdin. On the Diversity of Synthetic Data and its Impact on Training Large Language Models, October 2024a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2410.15226. arXiv:2410.15226 [cs].

- Chen et al. (2022) Xi Chen, Ali Zeynali, Chico Camargo, Fabian Flöck, Devin Gaffney, Przemyslaw Grabowicz, Scott A. Hale, David Jurgens, and Mattia Samory. SemEval-2022 task 8: Multilingual news article similarity. In Guy Emerson, Natalie Schluter, Gabriel Stanovsky, Ritesh Kumar, Alexis Palmer, Nathan Schneider, Siddharth Singh, and Shyam Ratan (eds.), Proceedings of the 16th International Workshop on Semantic Evaluation (SemEval-2022), pp. 1094–1106, Seattle, United States, July 2022. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/2022.semeval-1.155. URL https://aclanthology.org/2022.semeval-1.155/.

- Chen et al. (2024b) Yanran Chen, Hannes Gröner, Sina Zarrieß, and Steffen Eger. Evaluating diversity in automatic poetry generation. In Yaser Al-Onaizan, Mohit Bansal, and Yun-Nung Chen (eds.), Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 19671–19692, Miami, Florida, USA, November 2024b. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/2024.emnlp-main.1097. URL https://aclanthology.org/2024.emnlp-main.1097/.

- Christiano et al. (2017) Paul F Christiano, Jan Leike, Tom Brown, Miljan Martic, Shane Legg, and Dario Amodei. Deep reinforcement learning from human preferences. Advances in neural information processing systems, 30, 2017.

- Chung et al. (2025) John Joon Young Chung, Vishakh Padmakumar, Melissa Roemmele, Yuqian Sun, and Max Kreminski. Modifying large language model post-training for diverse creative writing, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.17126.

- Cobbe et al. (2021) Karl Cobbe, Vineet Kosaraju, Mohammad Bavarian, Mark Chen, Heewoo Jun, Lukasz Kaiser, Matthias Plappert, Jerry Tworek, Jacob Hilton, Reiichiro Nakano, Christopher Hesse, and John Schulman. Training verifiers to solve math word problems, 2021. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2110.14168.

- Computer (2023) Together Computer. Redpajama: An open dataset for training large language models. https://github.com/togethercomputer/RedPajama-Data, 2023. Accessed: 2025-09-23.

- Cox et al. (2021) Samuel Rhys Cox, Yunlong Wang, Ashraf Abdul, Christian Von Der Weth, and Brian Y. Lim. Directed diversity: Leveraging language embedding distances for collective creativity in crowd ideation. In Proceedings of the 2021 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 1–35, 2021.

- Cui et al. (2023) Ganqu Cui, Lifan Yuan, Ning Ding, Guanming Yao, Wei Zhu, Yuan Ni, Guotong Xie, Zhiyuan Liu, and Maosong Sun. Ultrafeedback: Boosting language models with high-quality feedback, 2023.

- Cui et al. (2025) Ganqu Cui, Yuchen Zhang, Jiacheng Chen, Lifan Yuan, Zhi Wang, Yuxin Zuo, Haozhan Li, Yuchen Fan, Huayu Chen, Weize Chen, Zhiyuan Liu, Hao Peng, Lei Bai, Wanli Ouyang, Yu Cheng, Bowen Zhou, and Ning Ding. The entropy mechanism of reinforcement learning for reasoning language models, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.22617.

- Damani et al. (2025) Mehul Damani, Isha Puri, Stewart Slocum, Idan Shenfeld, Leshem Choshen, Yoon Kim, and Jacob Andreas. Beyond binary rewards: Training lms to reason about their uncertainty, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.16806.

- DeepSeek-AI (2025) DeepSeek-AI. Deepseek-r1: Incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.12948.

- Dubois et al. (2023) Yann Dubois, Chen Xuechen Li, Rohan Taori, Tianyi Zhang, Ishaan Gulrajani, Jimmy Ba, Carlos Guestrin, Percy S Liang, and Tatsunori B Hashimoto. Alpacafarm: A simulation framework for methods that learn from human feedback. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36:30039–30069, 2023.

- Flesch (1948) Rudolph Flesch. A new readability yardstick. Journal of Applied Psychology, 32(3):221, 1948. URL https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18867058/.

- Ge et al. (2025) Tao Ge, Xin Chan, Xiaoyang Wang, Dian Yu, Haitao Mi, and Dong Yu. Scaling synthetic data creation with 1,000,000,000 personas, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.20094.

- Gwet (2008) Kilem Li Gwet. Computing inter-rater reliability and its variance in the presence of high agreement. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 61(1):29–48, 2008.

- Han et al. (2022) Rujun Han, Hong Chen, Yufei Tian, and Nanyun Peng. Go back in time: Generating flashbacks in stories with event temporal prompts. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.01898, 2022.

- He et al. (2024) Chaoqun He, Renjie Luo, Yuzhuo Bai, Shengding Hu, Zhen Leng Thai, Junhao Shen, Jinyi Hu, Xu Han, Yujie Huang, Yuxiang Zhang, Jie Liu, Lei Qi, Zhiyuan Liu, and Maosong Sun. Olympiadbench: A challenging benchmark for promoting agi with olympiad-level bilingual multimodal scientific problems, 2024.

- Hendrycks et al. (2021) Dan Hendrycks, Collin Burns, Saurav Kadavath, Akul Arora, Steven Basart, Eric Tang, Dawn Song, and Jacob Steinhardt. Measuring mathematical problem solving with the math dataset. NeurIPS, 2021.

- Hewitt et al. (2022) John Hewitt, Christopher D. Manning, and Percy Liang. Truncation sampling as language model desmoothing, 2022. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2210.15191.

- Holtzman et al. (2020) Ari Holtzman, Jan Buys, Li Du, Maxwell Forbes, and Yejin Choi. The curious case of neural text degeneration, 2020. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1904.09751.

- Hu et al. (2024) Hanxu Hu, Simon Yu, Pinzhen Chen, and Edoardo M. Ponti. Fine-tuning Large Language Models with Sequential Instructions, July 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2403.07794. arXiv:2403.07794 [cs].

- Huang et al. (2024) Zeyu Huang, Zihan Qiu, Zili Wang, Edoardo M. Ponti, and Ivan Titov. Post-hoc reward calibration: A case study on length bias, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.17407.

- Ismayilzada et al. (2025) Mete Ismayilzada, Antonio Laverghetta Jr, Simone A. Luchini, Reet Patel, Antoine Bosselut, Lonneke van der Plas, and Roger Beaty. Creative Preference Optimization, May 2025. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2505.14442. arXiv:2505.14442 [cs].

- Jain et al. (2024) Naman Jain, King Han, Alex Gu, Wen-Ding Li, Fanjia Yan, Tianjun Zhang, Sida Wang, Armando Solar-Lezama, Koushik Sen, and Ion Stoica. LiveCodeBench: Holistic and Contamination Free Evaluation of Large Language Models for Code, June 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2403.07974. arXiv:2403.07974 [cs].

- Janus (2022) Janus. Mysteries of mode collapse. https://www.lesswrong.com/posts/t9svvNPNmFf5Qa3TA/mysteries-of-mode-collapse, 2022. Accessed: 2025-07-16.

- Kim & Chilton (2025) Sean Kim and Lydia B. Chilton. Ai humor generation: Cognitive, social and creative skills for effective humor, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.07981.

- Kirk et al. (2024a) Hannah Rose Kirk, Alexander Whitefield, Paul Röttger, Andrew Bean, Katerina Margatina, Juan Ciro, Rafael Mosquera, Max Bartolo, Adina Williams, He He, Bertie Vidgen, and Scott A. Hale. The prism alignment dataset: What participatory, representative and individualised human feedback reveals about the subjective and multicultural alignment of large language models, 2024a. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.16019.

- Kirk et al. (2024b) Robert Kirk, Ishita Mediratta, Christoforos Nalmpantis, Jelena Luketina, Eric Hambro, Edward Grefenstette, and Roberta Raileanu. Understanding the effects of rlhf on llm generalisation and diversity, 2024b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.06452.

- Krippendorff (2018) Klaus Krippendorff. Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology. Sage publications, 2018.

- Lambert et al. (2025) Nathan Lambert, Jacob Morrison, Valentina Pyatkin, Shengyi Huang, Hamish Ivison, Faeze Brahman, Lester James V. Miranda, Alisa Liu, Nouha Dziri, Shane Lyu, Yuling Gu, Saumya Malik, Victoria Graf, Jena D. Hwang, Jiangjiang Yang, Ronan Le Bras, Oyvind Tafjord, Chris Wilhelm, Luca Soldaini, Noah A. Smith, Yizhong Wang, Pradeep Dasigi, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi. Tulu 3: Pushing frontiers in open language model post-training, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.15124.

- Lanchantin et al. (2025) Jack Lanchantin, Angelica Chen, Shehzaad Dhuliawala, Ping Yu, Jason Weston, Sainbayar Sukhbaatar, and Ilia Kulikov. Diverse preference optimization, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2501.18101.

- Lewkowycz et al. (2022) Aitor Lewkowycz, Anders Andreassen, David Dohan, Ethan Dyer, Henryk Michalewski, Vinay Ramasesh, Ambrose Slone, Cem Anil, Imanol Schlag, Theo Gutman-Solo, et al. Solving quantitative reasoning problems with language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 35:3843–3857, 2022.

- Li et al. (2016) Jiwei Li, Michel Galley, Chris Brockett, Jianfeng Gao, and Bill Dolan. A diversity-promoting objective function for neural conversation models. In Kevin Knight, Ani Nenkova, and Owen Rambow (eds.), Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, pp. 110–119, San Diego, California, June 2016. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/N16-1014. URL https://aclanthology.org/N16-1014/.

- Lin (2004) Chin-Yew Lin. ROUGE: A package for automatic evaluation of summaries. In Text Summarization Branches Out, pp. 74–81, Barcelona, Spain, July 2004. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/W04-1013/.

- Lin (2025) Jessy Lin. User simulators bridge rl with real-world interaction. https://jessylin.com/2025/07/10/user-simulators-1/, July 2025.

- Liu et al. (2024a) Chris Yuhao Liu, Liang Zeng, Jiacai Liu, Rui Yan, Jujie He, Chaojie Wang, Shuicheng Yan, Yang Liu, and Yahui Zhou. Skywork-reward: Bag of tricks for reward modeling in llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.18451, 2024a.

- Liu et al. (2024b) Yantao Liu, Zijun Yao, Rui Min, Yixin Cao, Lei Hou, and Juanzi Li. Rm-bench: Benchmarking reward models of language models with subtlety and style, 2024b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.16184.

- Liu et al. (2025) Zichen Liu, Changyu Chen, Wenjun Li, Penghui Qi, Tianyu Pang, Chao Du, Wee Sun Lee, and Min Lin. Understanding r1-zero-like training: A critical perspective, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2503.20783.

- Lu et al. (2025a) Li-Chun Lu, Miri Liu, Pin-Chun Lu, Yufei Tian, Shao-Hua Sun, and Nanyun Peng. Rethinking creativity evaluation: A critical analysis of existing creativity evaluations, 2025a. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.05470.

- Lu et al. (2025b) Ximing Lu, Melanie Sclar, Skyler Hallinan, Niloofar Mireshghallah, Jiacheng Liu, Seungju Han, Allyson Ettinger, Liwei Jiang, Khyathi Chandu, Nouha Dziri, and Yejin Choi. Ai as humanity’s salieri: Quantifying linguistic creativity of language models via systematic attribution of machine text against web text, 2025b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.04265.

- Lu et al. (2025c) Yining Lu, Dixuan Wang, Tianjian Li, Dongwei Jiang, Sanjeev Khudanpur, Meng Jiang, and Daniel Khashabi. Benchmarking language model creativity: A case study on code generation, 2025c. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.09007.

- Mandler (2014) George Mandler. The structure of value: Accounting for taste. In Affect and cognition, pp. 3–36. Psychology Press, 2014.

- Massey (1951) Frank J. Massey. The kolmogorov-smirnov test for goodness of fit. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 46(253):68–78, 1951. ISSN 01621459, 1537274X. URL http://www.jstor.org/stable/2280095.

- Mehrotra et al. (2024) Pronita Mehrotra, Aishni Parab, and Sumit Gulwani. Enhancing creativity in large language models through associative thinking strategies, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2405.06715.

- Meincke et al. (2024) Lennart Meincke, Ethan R Mollick, and Christian Terwiesch. Prompting diverse ideas: Increasing ai idea variance. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.01727, 2024.

- Meister et al. (2024) Nicole Meister, Carlos Guestrin, and Tatsunori Hashimoto. Benchmarking Distributional Alignment of Large Language Models, November 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2411.05403. arXiv:2411.05403.

- Meta (2024) Meta. The llama 3 herd of models, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2407.21783.

- Meyers-Levy & Tybout (1989) Joan Meyers-Levy and Alice M Tybout. Schema congruity as a basis for product evaluation. Journal of consumer research, 16(1):39–54, 1989.

- Narad et al. (2025a) Reuben Narad, Siddharth Suresh, Jiayi Chen, Pine S. L. Dysart-Bricken, Bob Mankoff, Robert Nowak, Jifan Zhang, and Lalit Jain. Which llms get the joke? probing non-stem reasoning abilities with humorbench, 2025a. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21476.

- Narad et al. (2025b) Reuben Narad, Siddharth Suresh, Jiayi Chen, Pine S. L. Dysart-Bricken, Bob Mankoff, Robert Nowak, Jifan Zhang, and Lalit Jain. Which LLMs Get the Joke? Probing Non-STEM Reasoning Abilities with HumorBench, July 2025b. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2507.21476. arXiv:2507.21476 [cs].

- Nguyen et al. (2025) Minh Nhat Nguyen, Andrew Baker, Clement Neo, Allen Roush, Andreas Kirsch, and Ravid Shwartz-Ziv. Turning Up the Heat: Min-p Sampling for Creative and Coherent LLM Outputs, May 2025. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2407.01082. arXiv:2407.01082 [cs].

- O’Mahony et al. (2024) Laura O’Mahony, Leo Grinsztajn, Hailey Schoelkopf, and Stella Biderman. Attributing mode collapse in the fine-tuning of large language models. In ICLR 2024 Workshop on Mathematical and Empirical Understanding of Foundation Models, 2024. URL https://openreview.net/forum?id=3pDMYjpOxk.

- OpenAI (2024) OpenAI. New embedding models and API updates. https://openai.com/index/new-embedding-models-and-api-updates/, 2024.

- OpenAI (2025a) OpenAI. Introducing deep research. https://openai.com/index/introducing-deep-research/, 2025a. Accessed: 2025-09-24.

- OpenAI (2025b) OpenAI. Introducing gpt-4.1 in the api. https://openai.com/index/gpt-4-1/, April 2025b. Accessed: 2025-09-14.

- Ouyang et al. (2022) Long Ouyang, Jeffrey Wu, Xu Jiang, Diogo Almeida, Carroll Wainwright, Pamela Mishkin, Chong Zhang, Sandhini Agarwal, Katarina Slama, Alex Ray, et al. Training language models to follow instructions with human feedback. Advances in neural information processing systems, 35:27730–27744, 2022.

- Padmakumar & He (2024) Vishakh Padmakumar and He He. Does Writing with Language Models Reduce Content Diversity?, July 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2309.05196. arXiv:2309.05196 [cs].

- Paech (2023) Samuel J. Paech. Eq-bench: An emotional intelligence benchmark for large language models, 2023.

- Qwen (2025a) Team Qwen. Qwen2.5 technical report, 2025a. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2412.15115.

- Qwen (2025b) Team Qwen. Qwen3 technical report, 2025b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.09388.

- Rafailov et al. (2024) Rafael Rafailov, Archit Sharma, Eric Mitchell, Stefano Ermon, Christopher D. Manning, and Chelsea Finn. Direct preference optimization: Your language model is secretly a reward model, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2305.18290.

- Reber et al. (2004) Rolf Reber, Norbert Schwarz, and Piotr Winkielman. Processing fluency and aesthetic pleasure: Is beauty in the perceiver’s processing experience? Personality and social psychology review, 8(4):364–382, 2004.

- Reddit (2023) Reddit. Reddit dad jokes, 2023. URL https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/oktayozturk010/reddit-dad-jokes/data.

- Setlur et al. (2024) Amrith Setlur, Saurabh Garg, Xinyang Geng, Naman Garg, Virginia Smith, and Aviral Kumar. Rl on incorrect synthetic data scales the efficiency of llm math reasoning by eight-fold, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2406.14532.

- Shaib et al. (2025) Chantal Shaib, Joe Barrow, Jiuding Sun, Alexa F. Siu, Byron C. Wallace, and Ani Nenkova. Standardizing the measurement of text diversity: A tool and a comparative analysis of scores, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2403.00553.

- Shi et al. (2024) Weijia Shi, Anirudh Ajith, Mengzhou Xia, Yangsibo Huang, Daogao Liu, Terra Blevins, Danqi Chen, and Luke Zettlemoyer. Detecting pretraining data from large language models, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.16789.

- Shur-Ofry et al. (2024) Michal Shur-Ofry, Bar Horowitz-Amsalem, Adir Rahamim, and Yonatan Belinkov. Growing a tail: Increasing output diversity in large language models, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.02989.

- Si et al. (2024) Chenglei Si, Diyi Yang, and Tatsunori Hashimoto. Can llms generate novel research ideas? a large-scale human study with 100+ nlp researchers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.04109, 2024.

- Snell et al. (2024) Charlie Snell, Jaehoon Lee, Kelvin Xu, and Aviral Kumar. Scaling LLM Test-Time Compute Optimally can be More Effective than Scaling Model Parameters, August 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2408.03314. arXiv:2408.03314 [cs].

- Sorensen et al. (2024) Taylor Sorensen, Jared Moore, Jillian Fisher, Mitchell Gordon, Niloofar Mireshghallah, Christopher Michael Rytting, Andre Ye, Liwei Jiang, Ximing Lu, Nouha Dziri, Tim Althoff, and Yejin Choi. A roadmap to pluralistic alignment, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2402.05070.

- Souly et al. (2024) Alexandra Souly, Qingyuan Lu, Dillon Bowen, Tu Trinh, Elvis Hsieh, Sana Pandey, Pieter Abbeel, Justin Svegliato, Scott Emmons, Olivia Watkins, and Sam Toyer. A strongreject for empty jailbreaks, 2024.

- Spangher et al. (2025) Alexander Spangher, Tenghao Huang, Philippe Laban, and Nanyun Peng. Creative planning with language models: Practice, evaluation and applications. In Maria Lomeli, Swabha Swayamdipta, and Rui Zhang (eds.), Proceedings of the 2025 Annual Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies (Volume 5: Tutorial Abstracts), pp. 1–9, Albuquerque, New Mexico, May 2025. Association for Computational Linguistics. ISBN 979-8-89176-193-3. doi: 10.18653/v1/2025.naacl-tutorial.1. URL https://aclanthology.org/2025.naacl-tutorial.1/.

- Stiennon et al. (2020) Nisan Stiennon, Long Ouyang, Jeff Wu, Daniel M. Ziegler, Ryan Lowe, Chelsea Voss, Alec Radford, Dario Amodei, and Paul Christiano. Learning to summarize from human feedback. In NeurIPS, 2020.

- Summers-Stay et al. (2023) Douglas Summers-Stay, Stephanie M. Lukin, and Clare R. Voss. Brainstorm, then select: a generative language model improves its creativity score. 2023. URL https://api.semanticscholar.org/CorpusID:259305709.

- Tan et al. (2025) Chenmien Tan, Simon Yu, Lanbo Lin, Ze Zhang, Yuanwu Xu, Chenhao Jiang, Tianyuan Yang, Sicong Xie, and Guannan Zhang. Rl2: Ray less reinforcement learning. https://github.com/ChenmienTan/RL2, 2025. GitHub repository.

- Tao et al. (2024) Shuchang Tao, Liuyi Yao, Hanxing Ding, Yuexiang Xie, Qi Cao, Fei Sun, Jinyang Gao, Huawei Shen, and Bolin Ding. When to trust llms: Aligning confidence with response quality. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.17287, 2024.

- Team (2025) Gemini Team. Gemini 2.5: Pushing the frontier with advanced reasoning, multimodality, long context, and next generation agentic capabilities, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2507.06261.

- Tian et al. (2023a) Katherine Tian, Eric Mitchell, Allan Zhou, Archit Sharma, Rafael Rafailov, Huaxiu Yao, Chelsea Finn, and Christopher D. Manning. Just Ask for Calibration: Strategies for Eliciting Calibrated Confidence Scores from Language Models Fine-Tuned with Human Feedback, October 2023a. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2305.14975. arXiv:2305.14975 [cs].

- Tian et al. (2023b) Yufei Tian, Anjali Narayan-Chen, Shereen Oraby, Alessandra Cervone, Gunnar Sigurdsson, Chenyang Tao, Wenbo Zhao, Yiwen Chen, Tagyoung Chung, Jing Huang, et al. Unsupervised melody-to-lyric generation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.19228, 2023b.

- Tian et al. (2025) Yufei Tian, Abhilasha Ravichander, Lianhui Qin, Ronan Le Bras, Raja Marjieh, Nanyun Peng, Yejin Choi, Thomas L. Griffiths, and Faeze Brahman. Macgyver: Are large language models creative problem solvers?, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2311.09682.

- Turgeman et al. (2025) Mor Turgeman, Chen Shani, and Dafna Shahaf. One joke to rule them all? on the (im)possibility of generalizing humor, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2508.19402.

- Tversky & Kahneman (1973) Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. Availability: A heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cognitive psychology, 5(2):207–232, 1973.

- Vijayakumar et al. (2016) Ashwin K Vijayakumar, Michael Cogswell, Ramprasath R Selvaraju, Qing Sun, Stefan Lee, David Crandall, and Dhruv Batra. Diverse beam search: Decoding diverse solutions from neural sequence models. arXiv preprint arXiv:1610.02424, 2016.

- Wang et al. (2025) Shenzhi Wang, Le Yu, Chang Gao, Chujie Zheng, Shixuan Liu, Rui Lu, Kai Dang, Xionghui Chen, Jianxin Yang, Zhenru Zhang, Yuqiong Liu, An Yang, Andrew Zhao, Yang Yue, Shiji Song, Bowen Yu, Gao Huang, and Junyang Lin. Beyond the 80/20 rule: High-entropy minority tokens drive effective reinforcement learning for llm reasoning, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2506.01939.

- Wang et al. (2019) Xuewei Wang, Weiyan Shi, Richard Kim, Yoojung Oh, Sijia Yang, Jingwen Zhang, and Zhou Yu. Persuasion for good: Towards a personalized persuasive dialogue system for social good. In Anna Korhonen, David Traum, and Lluís Màrquez (eds.), Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 5635–5649, Florence, Italy, July 2019. Association for Computational Linguistics. doi: 10.18653/v1/P19-1566. URL https://aclanthology.org/P19-1566/.

- Wang et al. (2023a) Yizhong Wang, Yeganeh Kordi, Swaroop Mishra, Alisa Liu, Noah A Smith, Daniel Khashabi, and Hannaneh Hajishirzi. Self-instruct: Aligning language models with self-generated instructions. In Proceedings of the 61st Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (Volume 1: Long Papers), pp. 13484–13508, 2023a.

- Wang et al. (2023b) Zhilin Wang, Yi Dong, Jiaqi Zeng, Virginia Adams, Makesh Narsimhan Sreedhar, Daniel Egert, Olivier Delalleau, Jane Polak Scowcroft, Neel Kant, Aidan Swope, and Oleksii Kuchaiev. Helpsteer: Multi-attribute helpfulness dataset for steerlm, 2023b.

- Wang et al. (2024) Zhilin Wang, Yi Dong, Olivier Delalleau, Jiaqi Zeng, Gerald Shen, Daniel Egert, Jimmy J. Zhang, Makesh Narsimhan Sreedhar, and Oleksii Kuchaiev. Helpsteer2: Open-source dataset for training top-performing reward models, 2024.

- Wei et al. (2024) Jason Wei, Nguyen Karina, Hyung Won Chung, Yunxin Joy Jiao, Spencer Papay, Amelia Glaese, John Schulman, and William Fedus. Measuring short-form factuality in large language models, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2411.04368.

- West & Potts (2025) Peter West and Christopher Potts. Base models beat aligned models at randomness and creativity, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2505.00047.

- Wong et al. (2024) Justin Wong, Yury Orlovskiy, Michael Luo, Sanjit A. Seshia, and Joseph E. Gonzalez. Simplestrat: Diversifying language model generation with stratification, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.09038.

- Xiao et al. (2024) Jiancong Xiao, Ziniu Li, Xingyu Xie, Emily Getzen, Cong Fang, Qi Long, and Weijie J Su. On the algorithmic bias of aligning large language models with rlhf: Preference collapse and matching regularization. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.16455, 2024.

- Xiao et al. (2025) Tim Z Xiao, Johannes Zenn, Zhen Liu, Weiyang Liu, Robert Bamler, and Bernhard Schölkopf. Flipping against all odds: Reducing llm coin flip bias via verbalized rejection sampling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2506.09998, 2025.

- Xiong et al. (2024) Miao Xiong, Zhiyuan Hu, Xinyang Lu, Yifei Li, Jie Fu, Junxian He, and Bryan Hooi. Can LLMs Express Their Uncertainty? An Empirical Evaluation of Confidence Elicitation in LLMs, March 2024. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2306.13063. arXiv:2306.13063 [cs].

- Xu et al. (2025) Weijia Xu, Nebojsa Jojic, Sudha Rao, Chris Brockett, and Bill Dolan. Echoes in ai: Quantifying lack of plot diversity in llm outputs. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 122(35), August 2025. ISSN 1091-6490. doi: 10.1073/pnas.2504966122. URL http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2504966122.

- Yang & Holtzman (2025) Chenghao Yang and Ari Holtzman. How Alignment Shrinks the Generative Horizon, June 2025. URL http://arxiv.org/abs/2506.17871. arXiv:2506.17871 [cs].

- Yang et al. (2024) Daniel Yang, Yao-Hung Hubert Tsai, and Makoto Yamada. On verbalized confidence scores for llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14737, 2024.

- Yang et al. (2022a) Kevin Yang, Dan Klein, Nanyun Peng, and Yuandong Tian. Doc: Improving long story coherence with detailed outline control. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10077, 2022a.

- Yang et al. (2022b) Kevin Yang, Yuandong Tian, Nanyun Peng, and Dan Klein. Re3: Generating longer stories with recursive reprompting and revision. arXiv preprint arXiv:2210.06774, 2022b.

- Ye et al. (2025) Yixin Ye, Zhen Huang, Yang Xiao, Ethan Chern, Shijie Xia, and Pengfei Liu. Limo: Less is more for reasoning, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.03387.

- Yun et al. (2025) Longfei Yun, Chenyang An, Zilong Wang, Letian Peng, and Jingbo Shang. The price of format: Diversity collapse in llms. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.18949, 2025.

- Zajonc (1968) Robert B Zajonc. Attitudinal effects of mere exposure. Journal of personality and social psychology, 9(2p2):1, 1968.

- Zhang et al. (2021) Hugh Zhang, Daniel Duckworth, Daphne Ippolito, and Arvind Neelakantan. Trading off diversity and quality in natural language generation. In Anya Belz, Shubham Agarwal, Yvette Graham, Ehud Reiter, and Anastasia Shimorina (eds.), Proceedings of the Workshop on Human Evaluation of NLP Systems (HumEval), pp. 25–33, Online, April 2021. Association for Computational Linguistics. URL https://aclanthology.org/2021.humeval-1.3/.

- Zhang et al. (2024a) Tianhui Zhang, Bei Peng, and Danushka Bollegala. Improving diversity of commonsense generation by large language models via in-context learning. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2024, pp. 9226–9242, 2024a.

- Zhang et al. (2024b) Tianhui Zhang, Bei Peng, and Danushka Bollegala. Improving diversity of commonsense generation by large language models via in-context learning, 2024b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2404.16807.

- Zhou et al. (2025) Kuan Lok Zhou, Jiayi Chen, Siddharth Suresh, Reuben Narad, Timothy T. Rogers, Lalit K Jain, Robert D Nowak, Bob Mankoff, and Jifan Zhang. Bridging the creativity understanding gap: Small-scale human alignment enables expert-level humor ranking in llms, 2025. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.20356.

- Zhou et al. (2024) Xuhui Zhou, Hao Zhu, Leena Mathur, Ruohong Zhang, Haofei Yu, Zhengyang Qi, Louis-Philippe Morency, Yonatan Bisk, Daniel Fried, Graham Neubig, and Maarten Sap. Sotopia: Interactive evaluation for social intelligence in language agents, 2024. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2310.11667.

- Zhu et al. (2025a) Alan Zhu, Parth Asawa, Jared Quincy Davis, Lingjiao Chen, Boris Hanin, Ion Stoica, Joseph E. Gonzalez, and Matei Zaharia. Bare: Leveraging base language models for few-shot synthetic data generation, 2025a. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2502.01697.

- Zhu et al. (2025b) Xiao Zhu, Chenmien Tan, Pinzhen Chen, Rico Sennrich, Yanlin Zhang, and Hanxu Hu. Charm: Calibrating reward models with chatbot arena scores, 2025b. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/2504.10045.

Appendix Contents

Appendix A Contribution Statement

Jiayi Zhang and Simon Yu co-led the design and execution of experiments.

Jiayi Zhang established the core proof of concept for the intuition on the dialogue simulation task important for the project, proposed tasks and ablations, contributed to the codebase, and conducted experiments on dialogue simulation, open-ended QA, commonsense reasoning, random number generation, probing the pretraining and verbalized distribution, synthetic data generation, and human study on creative writing.

Simon Yu implemented the core codebase, proposed tasks and ablations, refined the initial theoretical proof, validated the typicality bias on multiple preference datasets, conducted experiments on creative writing, synthetic data generation, safety evaluation, and ablation studies, and led the open source and packaged the codebase into a library.

Derek Chong provided the core intuition of the project, proposed tasks, developed the theoretical proof on mode collapse in post-training alignment, conducted its empirical and statistical validation, helped with experimental design, and packaged the codebase into a library.

Anthony Sicilia contributed to the discussions on the dialogue simulation tasks and collaborated with Derek Chong to refine the theoretical proof.

Michael Tomz and Christopher Manning provided funding for Derek Chong, steered the initial research direction, offered feedback across the project, and assisted with the review and proofreading of the manuscript.

Weiyan Shi supervised the research, steered the project direction, provided funding support, gathered external feedback, polished the figures, and led the final comprehensive editing and review process.

All authors reviewed the manuscript and provided feedback.

Appendix B Limitations

We discuss the following limitations of our method.

Computational Cost and Latency.

One major trade-off of Verbalized Sampling (VS) is an increased computational budget at inference time. Generating a distribution of candidates is more costly in terms of latency and token usage than generating a single response. In our experiments, we have controlled the total computing budget, but this limitation may still constrain its applicability in latency-sensitive or resource-constrained environments.

Dependence on Model Scale and Capability.

The performance gains from VS are positively correlated with model scale. Our results indicate that larger, more capable models can better handle the cognitive burden of the probability estimation and structured output. Conversely, less capable models may lack the reasoning and instruction-following abilities needed to fully benefit from VS, occasionally resulting in a degradation in output quality. A potential solution is to improve their calibration through further training (Damani et al., 2025). The method’s effectiveness is therefore contingent on a sufficient level of underlying model capability.

Appendix C Future Directions

Mitigating Bias in Reward Models.

As we discussed in Section˜3, the major cause of mode collapse is the cognitive typicality biases embedded in the preference data and, therefore, affecting the reward models. These biases can cause the reward models to favor stereotypical outputs or exhibit certain biases (e.g. towards length, style (Liu et al., 2024b)). To tackle this challenge, recent works have tried different calibration techniques that produce more balanced reward models. For example, Huang et al. (2024) introduced post-hoc calibration methods that specifically address length and stylistic biases. On the other hand, Zhu et al. (2025b) took a different approach and used Chatbot Arena rankings collected from the public to calibrate their reward models. To reduce mode collapse, a promising future step is to mitigate reward model bias and achieve broader preference coverage through pluralistic alignment (Sorensen et al., 2024).

Inference-time Scaling.

Verbalized Sampling presents an alternative approach to inference-time scaling. Conventional methods (Snell et al., 2024; Brown et al., 2024) often rely on repeated sampling from a single prompt; however, as we have shown, this method can be vulnerable to mode collapse and suffer from limited output diversity (Yang & Holtzman, 2025). By contrast, Verbalized Sampling elicits a broader distribution of responses that more faithfully represents the LLM’s underlying generative capabilities. This enhanced diversity can be particularly promising for improving the action space exploration in RL training (Cui et al., 2025; Wang et al., 2025). For instance, the diverse outputs from verbalized sampling could enable exploration of less probable but potentially correct solutions, which can be reinforced during RL training to improve performance. This is a promising direction for future work.

Appendix D Use of Large Language Models

We disclose our use of large language models (LLMs) in this work. We employed LLMs in two capacities:

Paper Writing Assistance: We used LLMs to improve the clarity and presentation of our work, including initial drafting of subsections, refinement of technical exposition, grammar and style improvements, and minor proof-editing tasks. We also used Deep Research (OpenAI, 2025a) to assist with literature search and identifying relevant prior work.

Research Assistance: We utilized LLMs to help generate experimental code, assist in formalizing theoretical concepts, and support the implementation of our methods. All LLM-generated code and theoretical formulations were thoroughly reviewed, verified, and validated by the authors.

We emphasize that all core scientific contributions originate from the authors: LLM outputs were treated as preliminary drafts requiring substantial human oversight, verification, and modification. The authors take full responsibility for all content in this submission, including any text or code initially generated with LLM assistance.

Appendix E Typicality Bias Causes Mode Collapse

E.1 Typicality Bias in HelpSteer: Experimental Validation Detail

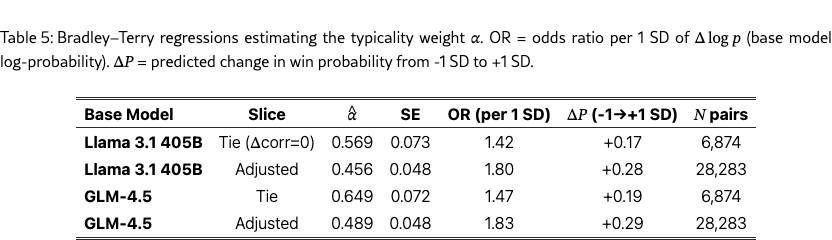

As outlined in section˜3.1, we test the “typicality bias” hypothesis on the training split of HelpSteer (Wang et al., 2023b). We use per-response ratings for correctness and overall helpfulness to form within-prompt pairs matched on correctness (i.e., ), and compute per-token log-likelihoods under two base models, : Llama 3.1 405B Base and GLM 4.5 Base. We then fit the Bradley–Terry logistic model implied by equation 1, with the binary outcome “which response receives higher helpfulness” and predictor (difference in average log-likelihood under ). The coefficient on is the estimate of . Results are provided in Table 5.

On the correctness-matched pairs, we obtain for Llama 3.1 Base and for GLM 4.5 Base (cluster-robust SEs; both ). Interpreted as odds ratios per one standard deviation in , this corresponds to - higher odds of the more typical response being judged more helpful, a 17-19 percentage point increase in win probability. Using all within-prompt pairs and adding as a covariate yields similar but slightly smaller effects (–), confirming that the typicality bias predicts helpfulness above and beyond correctness. These results provide empirical evidence for a positive term in equation 1, i.e., human annotators reward base-model typicality independent of semantic correctness.

E.2 Typicality Bias in More Preference Datasets

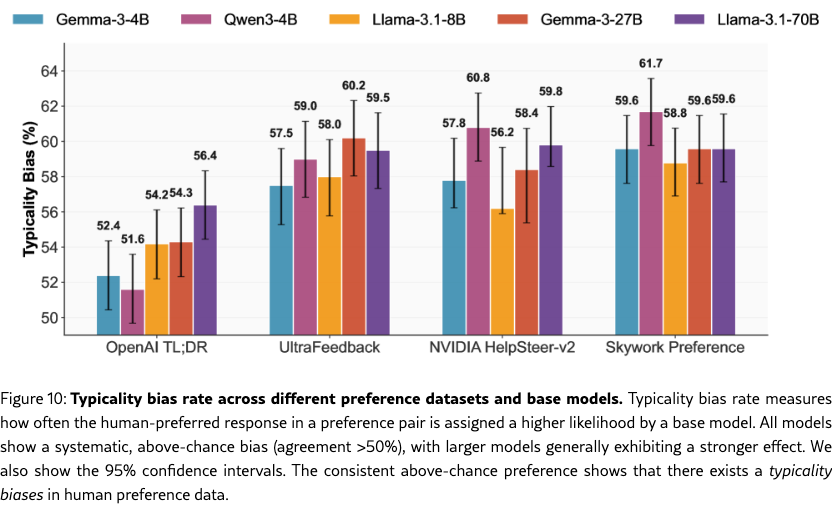

We also investigate whether typicality bias exists in more preference datasets and base models. We evaluate four widely-used preference datasets on five representation base models (Gemma-3-4B, Qwen3-4B, Gemma-3-27B, Llama-3.1-8B, Llama-3.1-70B). The preference datasets span different domains and annotation methodologies: OpenAI TL;DR (Stiennon et al., 2020) (human-annotated summarization), UltraFeedback (Cui et al., 2023) (GPT-4 annotations), NVIDIA HelpSteer-v2 (Wang et al., 2024) (human ratings), and Skywork Preference (Liu et al., 2024a) (hybrid).

Experimental Setup. As most of these datasedo not have separate labels for correctness and helpfulness, it is infeasible to apply the Bradley-Terry logistic model as before. Instead, for each preference dataset, we calculate the typicality bias rate, which measures how often the human-preferred response in a preference pair is assigned a higher likelihood by a base model. We sample 2,500 preference pairs from each dataset and compute the typicality bias ratio with 95% confidence intervals.

Results. The results are shown in Figure˜10. Our findings reveal the underlying typicality biases across all base models. Most critically, the typicality bias rate consistently exceed the 50% chance baseline by 4-12 percentage points, indicating that human annotators do exhibit preferences towards more typical texts under various base models. Besides, larger models (e.g., Gemma-3-27B, Llama-3.1-70B) show higher typicality bias rates.

E.3 How Typicality Bias Causes Mode Collapse

Rafailov et al. (2024) shows that the closed-form solution to the KL-regularized RLHF objective in equation 2 is the following:

| (4) |

Substituting our reward decomposition from equation 1, we have:

| (5) |

Since the partition function contains the same factor, this cancels, yielding:

| (6) |

This power transform with exponent (when ) sharpens the reference distribution, amplifying its modes while suppressing the tails. The effect strengthens as the typicality bias increases or the KL penalty decreases. In the limiting case where true task utility is approximately flat over a set , the optimal policy reduces to on , producing mode collapse toward the most typical responses under .

E.4 Different Prompts Collapse to Different Modes: An Analysis of Prompt Capability Under Mode Collapse

Setup.

For a fixed prompt , we are interested in recovering the full diversity inherent to the reference policy . We hope to do so for some corresponding affected set , where is mode collapsed. Specifically, mode collapse means:

| (7) |

and is the Dirac function:

To recover diversity, we assume a new prompt , which is possibly distinct from , and a (new) sampling strategy that may extend beyond direct sampling of the policy . Since we demonstrated the potential for mode collapse of independent of prompt, we also assume remains mode collapsed on some set .

A Stronger Notion of Mode Collapse for .

For tractability, we assume is mode collapsed on all of (). While coarse, this assumption is justified in practice: repeated samples from return the same completion with high probability, implying that the total probability mass away from this completion (the mode ) is negligible. From the perspective of observable sampling behavior, is effectively mode collapsed on all of ; it is mode collapsed to on some set and has near-zero probability everywhere else.

Specifying Sampling Procedures.

To compare probabilities between different prompts of and , we need to account for how a single completion is chosen from the result of each prompt. This process defines a completion’s new (non-mode-collapsed) probability under the prompt.

-

1.