SCRIBE: Structured Mid-Level Supervision for Tool-Using Language Models

Abstract

Training reliable tool-augmented agents remains a significant challenge due to the difficulty of credit assignment in multi-step reasoning. While Process-level Reward Models (PRMs) offer a potential solution, standard LLM-based judges often provide inconsistent signals because they lack granular, task-specific rubrics to disentangle high-level planning from low-level execution. In this work, we propose SCRIBE (Skill-Conditioned Reward with Intermediate Behavioral Evaluation), a reinforcement learning framework that intervenes at a novel mid-level abstraction. SCRIBE anchors reward modeling in a curated library of Skill Prototypes, transforming open-ended LLM evaluation into a constrained verification task. By routing subgoals to specific prototypes, we provide the judge with precise rubrics that significantly reduce reward variance. Empirical results demonstrate that SCRIBE achieves state-of-the-art performance across reasoning and tool-use benchmarks; notably, it improves the AIME25 score of a Qwen3-4B model from 43.3% to 63.3% and substantially enhances success rates in complex multi-turn tool interactions. Furthermore, our analysis of training dynamics characterizes a co-evolution between levels, where mid-level skill mastery serves as a precursor to the emergence of strategic high-level planning. Finally, we show that SCRIBE is additive to low-level tool optimizations, offering a scalable and complementary approach to building more autonomous and reliable agents.

SCRIBE: Structured Mid-Level Supervision for Tool-Using Language Models

Yuxuan Jiang1 Francis Ferraro1 1University of Maryland, Baltimore County yuxuanj1@umbc.edu

1 Introduction

Tool-integrated reasoning augments the reasoning process with external tool invocations, providing verifiable signals and the potential to improve a model’s performance ceiling comparing to traditional text-only reasoning Yao et al. (2023); Qian et al. (2025). However, the large and diverse space of available tools makes learning effective tool use challenging Xue et al. (2025); Liu et al. (2024). Models often fail to achieve intermediate reasoning objectives due to unreliable tool selection, invocation, or result integration, limiting the benefits of tool augmentation. As a result, enabling models to reliably use tools remains a central challenge in tool-augmented reasoning.

Recent advances in agentic reinforcement learning have demonstrated promising gains in tool-augmented reasoning tasks Zhang et al. (2025a). However, training tool-using agents remains challenging due to credit assignment. In multi-step and multi-tool settings, outcome-level rewards are often insufficient, as errors may arise from planning, execution, or improper tool use, which are difficult to disentangle from final outcomes alone Qian et al. (2025). To mitigate this issue, prior work has explored process-level reward modeling (PRM), typically relying on LLM-based judges to score intermediate reasoning steps or full trajectories Yu et al. (2025b); Zhang et al. (2025c); Khalifa et al. (2025); Li et al. (2025a). Despite scalability, such judges often yield inconsistent signals due to underspecified reward criteria.

For example, in a multi-step mathematical problem, an LLM-based judge may assign a high score to a reasoning trajectory simply because the final numerical answer is correct, while overlooking logical flaws in intermediate tool usage, such as misinterpreting an API response or relying on an unjustified computational shortcut. Conversely, a step may be penalized due to a minor, non-fatal syntax error in a tool call, even when the underlying reasoning strategy is sound and the error does not affect the final outcome. Without a rigorous rubric that distinguishes between strategic planning and technical execution, such inconsistent reward signals obscure which intermediate decisions actually contributed to success or failure, hindering effective learning during training.

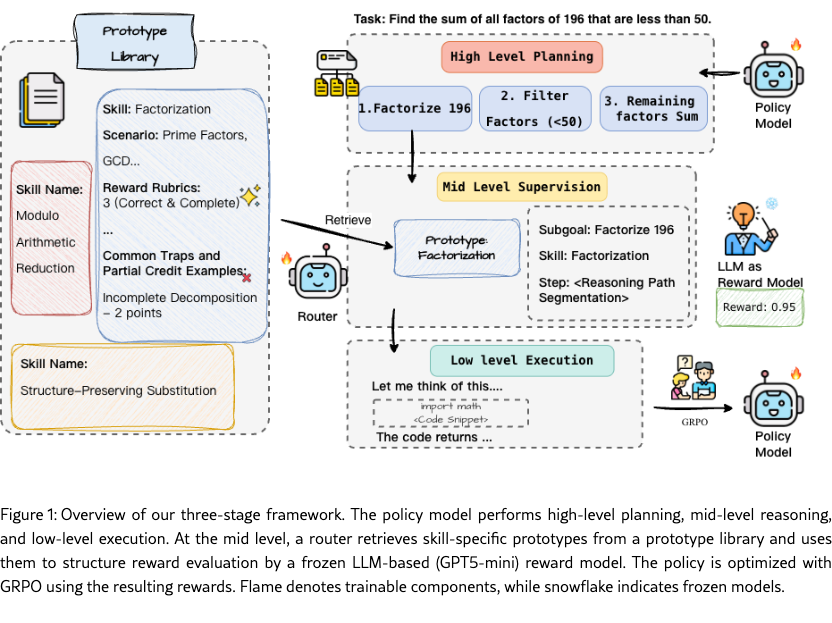

While prior work often oscillates between supervising high-level plans or low-level tool execution, we argue that the mid-level abstraction provides a more effective point of intervention for robust credit assignment. As illustrated in Figure 1, we propose SCRIBE (Skill-Conditioned Reward with Intermediate Behavioral Evaluation), a framework that provides structured supervision for tool-augmented reasoning . SCRIBE centers on a curated library of Skill Prototypes, each representing a canonical mid-level reasoning pattern distilled from clusters of semantically similar subgoals and skills. An auxiliary Router maps raw reasoning trajectories into structured representations and associates each subgoal with its corresponding prototype. Crucially, this taxonomic anchoring enables a more reliable reward scheme by grounding open-ended LLM judgments in structured constraints. Rather than tasking a judge with evaluating arbitrary reasoning steps—a process often prone to "hallucinatory" rewards or inconsistent criteria—SCRIBE provides the judge with a context-specific rubric defined by the routed Skill Prototype. By narrowing the evaluation space from subjective logical assessment to the verification of specific skill execution, we effectively transform the reward modeling from an open-ended generation task into a constrained verification task. This significantly reduces reward variance and ensures that the reinforcement learning signal is both dense and grounded in specific reasoning behaviors.

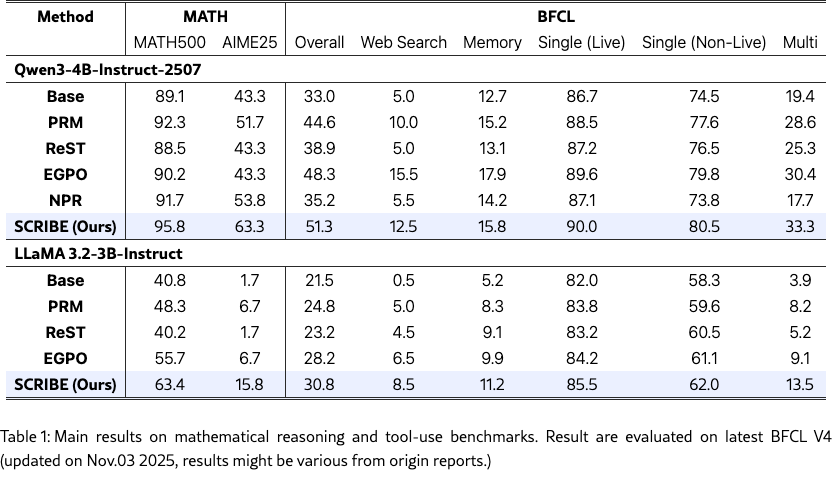

We evaluate SCRIBE on challenging benchmarks for mathematical reasoning (MATH, AIME25) and tool-use (BFCL V4). As shown in Table 1, SCRIBE consistently outperforms state-of-the-art RL baselines. Notably, on the AIME25 benchmark, our approach improves the Qwen3-4B-instruct-2507 model from 43.3% to 63.3%. In complex tool-use scenarios (BFCL Multi), SCRIBE achieves a 33.3% success rate, demonstrating its superior ability to handle multi-step tool interactions through precise credit assignment.

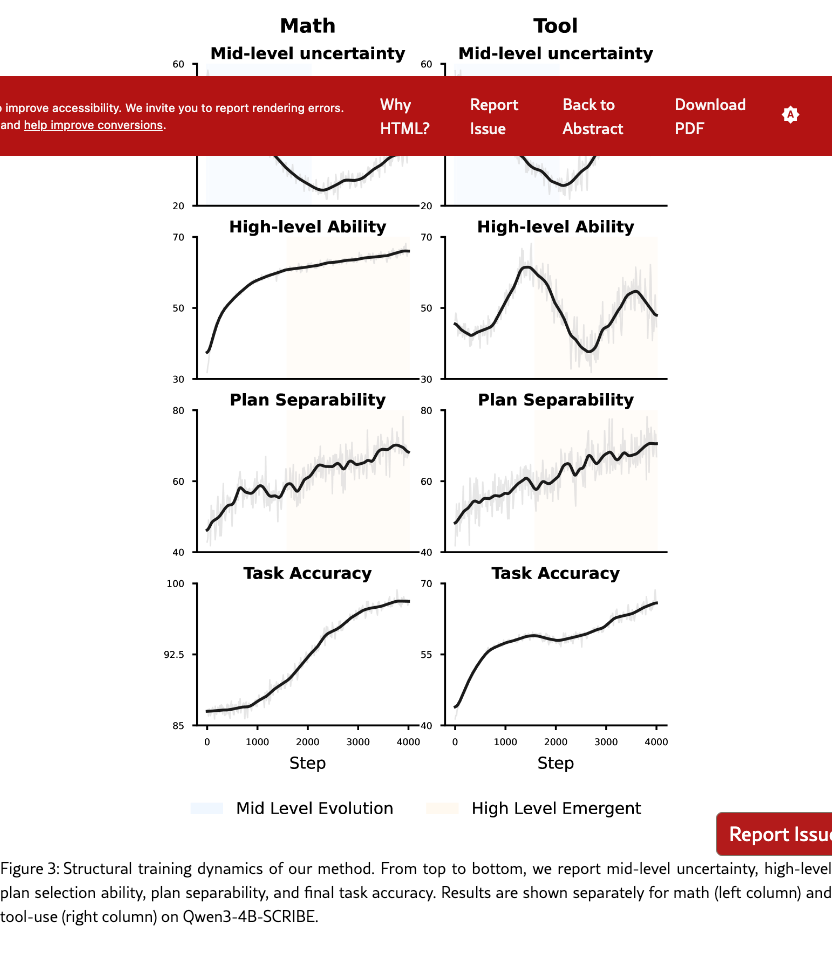

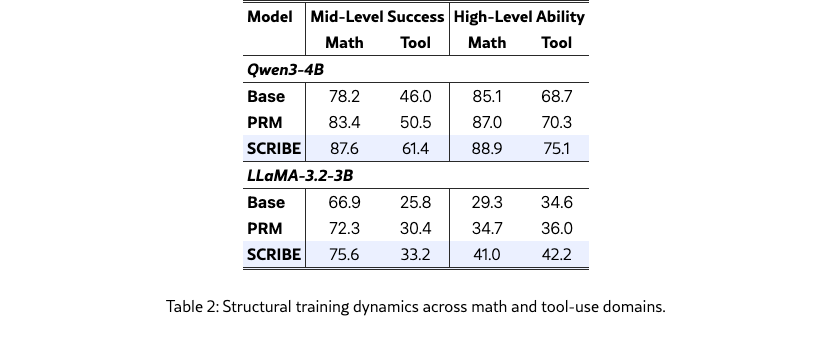

Beyond performance gains, our analysis of training dynamics (Sec. 6.1) reveals a co-evolution between mid-level execution and high-level planning. As shown in Figure 3, the mastery of intermediate skills acts as a precursor to the emergence of strategic coherence. These results indicate that mid-level supervision does not merely improve local execution fidelity, but fundamentally reshapes the model’s high-level ability by providing a more stable foundation for long-horizon planning.

In summary, our contributions are as follows:

-

•

We formalize a three-level hierarchy for tool-use, identifying mid-level skills as the optimal point for credit assignment.

-

•

We introduce SCRIBE, which anchors rewards in Skill Prototypes to transform noisy evaluation into grounded verification.

-

•

We get empirical performance gain on results and characterize a co-evolution where mid-level mastery facilitates high-level planning.

-

•

We demonstrate that SCRIBE complements low-level tool optimization, yielding superior synergistic performance in Sec. 6.2.

2 Related Works

2.1 Tool-Integrated Reasoning with Agentic Reinforcement Learning

Tool-integrated reasoning extends large language models by enabling them to invoke external tools such as code interpreters and search engines, substantially improving the limits of purely textual reasoning Yao et al. (2023); Wang et al. (2024); Liao et al. (2024). This paradigm builds upon the diverse foundational capabilities of LLMs in reasoning, knowledge retrieval, and instruction following Jiang and Ferraro (2024); Zhang et al. (2025b); Li et al. (2025c). Early tool-use frameworks such as ToRA Gou et al. (2023) and Toolformer Schick et al. (2023) rely primarily on supervised fine-tuning to teach models when and how to invoke external tools. Building on this line, a series of recent agentic reinforcement learning approaches ,likeToolRL Qian et al. (2025), DeepSeek-R1 Guo et al. (2025), explicitly model tool usage as actions and optimize multi-step tool interaction via reward design, such as DAPO Yu et al. (2025a) and GRPO Liu et al. (2025).

Despite their success, most existing methods concentrate on low-level tool-use behaviors, focusing on richer invocation patterns, improved execution accuracy, or increased autonomy at the action level Dong et al. (2025); Xu et al. (2025); Li et al. (2025b), rather than evaluating or supervising plan-level discrimination and high-level decision structure. In contrast, it remains underexplored whether tool use improves mid-level reasoning quality, such as subgoal execution and intermediate abstraction, or translates into stronger high-level reasoning. Our work addresses this gap by examining how agentic tool use affects reasoning competence beyond surface-level tool invocation.

2.2 Progress Reward Modeling with LLM-as-Judge

Progress reward modeling extends outcome-based reward modeling by evaluating the correctness of intermediate reasoning steps rather than final answer only, thereby providing denser supervision for improving reasoning performance Lightman et al. (2023); Setlur et al. (2024). Recent work increasingly adopts LLM-as-judge frameworks to support PRM, leveraging their low annotation cost and strong generalization to produce large-scale supervision signals for agentic reinforcement learning Li et al. (2025a); Choudhury (2025).

Despite these advantages, LLM-based judges are known to suffer from vulnerability and inconsistency, which can induce reward hacking and destabilize training Zhao et al. (2025); Agarwal et al. (2025). Such issues arise when models exploit weaknesses in the reward signal rather than improving genuine reasoning quality. Our work explicitly analyzes this failure mode and proposes a more consistent and accurate evaluation protocol, leading to improved stability and performance.

2.3 Problem Decomposition and skills in Reasoning

Decomposing complex reasoning problems into a sequence of simpler subgoals has been shown to improve performance on challenging tasks Xiang et al. (2025); Teng et al. (2025); Shi et al. (2022). With an appropriate decomposition, each subgoal typically corresponds to a dominant reasoning skill, where a skill denotes a reusable reasoning operation, such as algebraic factorization or querying external information Dalal et al. (2024).

Prior work has shown that skills form a stable and model-recognizable level of structure within LLMs Jiang et al. (2025). Compared to step-level decomposition, skill-based decomposition enables more consistent identification of reusable reasoning patterns across problems. Building on this insight, our work investigates how strengthening tool-related skills can improve subgoal execution and, consequently, overall reasoning performance.

3 Method: Decomposition, Clustering, prototype

Our framework, SCRIBE, decomposes the training process into three core stages: skill-level abstraction, structured reward evaluation, and policy optimization. As illustrated in the system overview (Figure 1), we move beyond raw process-level rewards by introducing a mid-level "semantic bridge." We first distill reasoning trajectories into a library of reusable Skill Prototypes. During training, an auxiliary Router maps the student’s rollouts to these prototypes, allowing an LLM-based judge to provide rewards that are calibrated against a consistent taxonomic rubric rather than subjective inference. Finally, the model is optimized using GRPO, benefiting from the densified and stabilized credit assignment signals.

3.1 Mid-Level Skill Abstraction

We formalize a trajectory as an ordered sequence of triples, where each step represents a non-overlapping span of the reasoning trace. We show a simplified verision of prompt here and the full prompt is provided in Appendix D. Our SCRIBE targets this mid-level abstraction to bridge the gap between high-level planning and low-level execution.

Prototype Construction.

To build this abstraction, we first decompose trajectories into subgoals and associated skills using the prompting scheme in Appendix A. We then apply a hierarchical clustering approach—utilizing HDBSCAN for dense clusters and K-means as a fallback—to group semantically similar reasoning patterns. For each cluster, we distill a representative Skill Prototype that aggregates usage contexts, intermediate objectives, and canonical reasoning patterns while abstracting away instance-specific details like concrete numerical values.

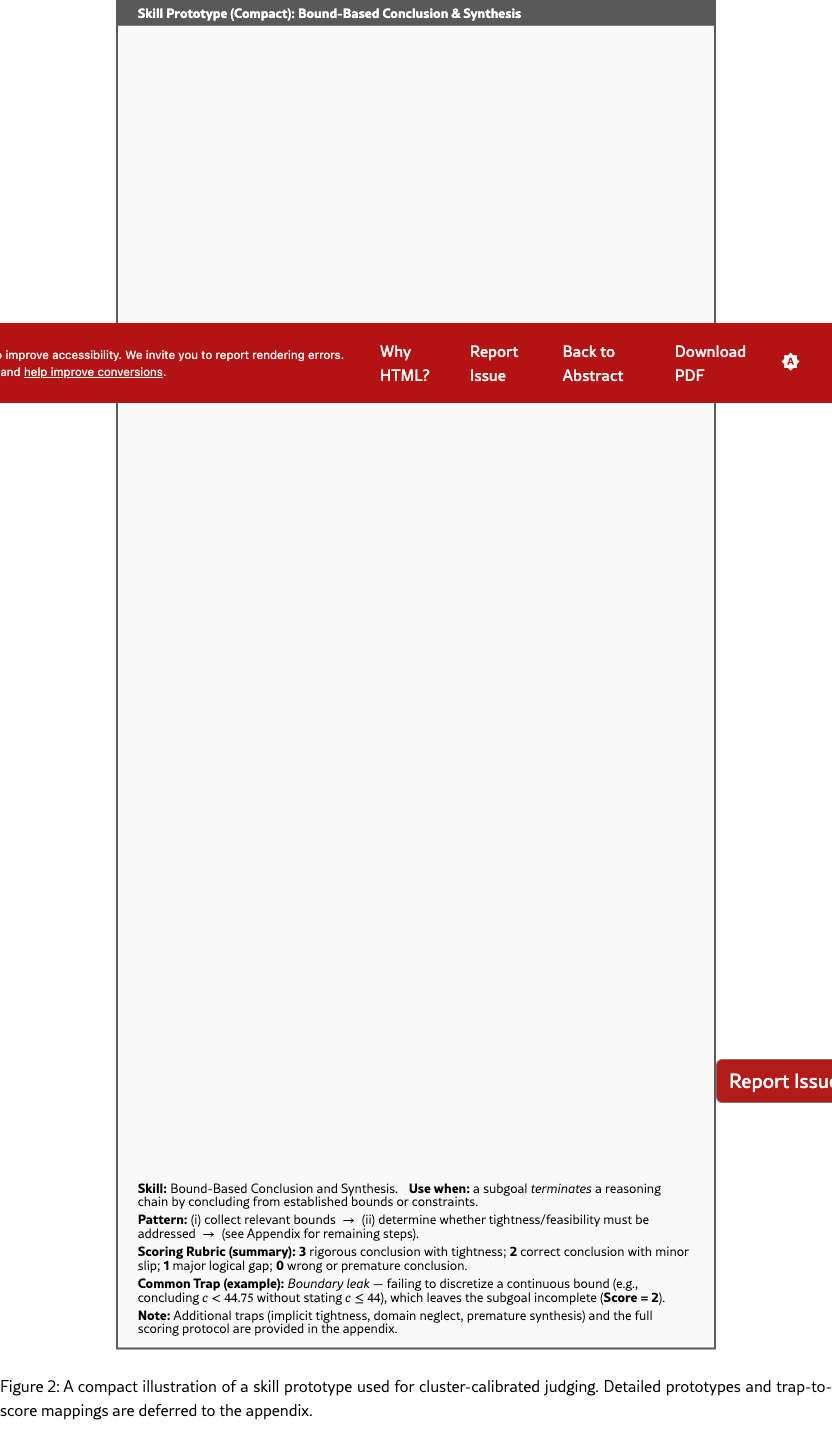

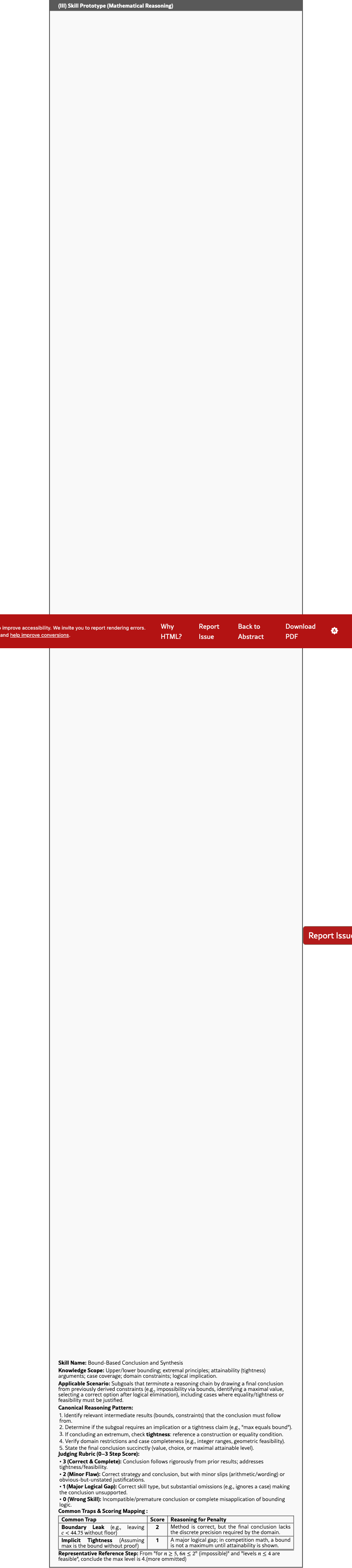

Structured Verification via Prototypes.

Skill Prototypes transform subjective, open-ended judging into structured verification. As shown in the Bound-Based Conclusion example (Figure 2), once a step is routed to a prototype, the LLM judge is provided with a precise, checklist-style rubric. For instance, instead of vaguely rewarding "logical correctness," the prototype requires verifying if the agent properly addressed inequality strictness or identified necessary bounds. Crucially, each prototype defines Common Traps—such as a "Boundary Leak" (e.g., failing to discretize a continuous bound like to )—and maps them to specific penalty scores. This granularity ensures the reward signal is a diagnostic reflection of skill mastery rather than a biased estimate based solely on the final outcome.

3.2 Skill-Conditioned Reward and Optimization

Routing and Reward Evaluation.

To recover mid-level structure during training, we train a lightweight Router (Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507) to map raw trajectories into structured triples. During RL, the Router assigns student-generated subgoals to their corresponding Skill Prototypes. A judge LLM then evaluates these subgoals with scores in conditioned on the prototype’s checklist. To ensure reward reliability, we adopt a calibration protocol that (i) verifies rewards across multiple prompt variants, (ii) leverages subgoal-level accuracy statistics, and (iii) monitors consistency via repeated evaluation on fixed anchor subgoals. The final process reward is a weighted average of these calibrated subgoal scores. Full details are provided in Appendix A.

Policy Optimization with Adaptive Prototypes.

The student model is optimized using the GRPO objective based on these skill-conditioned rewards. To mitigate distributional shifts, we implement an adaptive refresh mechanism: every 1,000 training steps, we re-cluster accumulated trajectories to update the Skill Prototype library. This ensures that the supervision remains aligned with the model’s evolving reasoning patterns while maintaining stable mid-level abstractions for consistent credit assignment.

4 Experimental Setup

Experimental Settings.

We conduct reinforcement learning experiments using Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507111https://huggingface.co/Qwen/Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507 as the primary policy model, and additionally evaluate generality with LLaMA-3.2-3B-Instruct222https://huggingface.co/meta-llama/Llama-3.2-3B-Instruct. Process-level rewards are provided by an LLM-based judge (GPT-5-mini)333https://platform.openai.com/docs/models/gpt-5-mini. The Router is implemented as a lightweight model fine-tuned from the same base model as the policy.

Training is performed on approximately 10k problems sampled from the MATH dataset444https://huggingface.co/datasets/open-r1/OpenR1-Math-220k/tree/main and the ToolACE Liu et al. (2024) dataset. These data are used to construct skill annotations, train the Router, and perform GRPO-based policy optimization. For mathematical reasoning tasks, we primarily rely on the Python interpreter, which is natively supported by Qwen3.

Applying the skill clustering protocol described in Sec. 3.1, we obtain a compact mid-level skill space. Initially, clustering yields 418 skill clusters for mathematical reasoning and 472 clusters for tool-use trajectories. Clusters are periodically refreshed during training to incorporate newly observed trajectories. After convergence, the skill space contains 424 clusters for mathematical reasoning and 503 clusters for BFCL-style tool-use tasks.

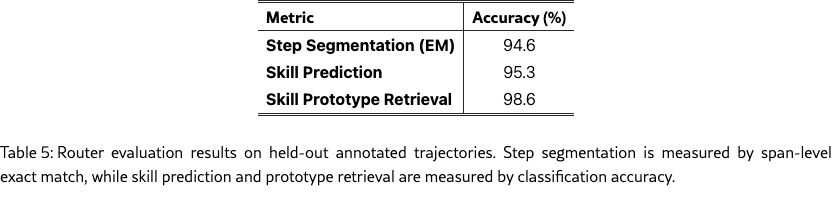

The Router is trained on judge-annotated trajectories with a 9:1 train–test split, achieving 98.6% accuracy in skill prototype retrieval on held-out data. Detailed subgoal-, skill-, and step-level evaluation metrics are reported in Appendix B.

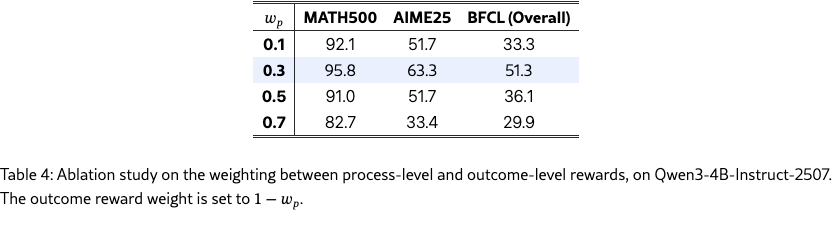

During training, we combine process-level and final-answer rewards, with weights of 0.3 and 0.7 respectively. Unless otherwise specified, this reward composition is used throughout.

The policy model is optimized using GRPO with skill-conditioned rewards. We evaluate mathematical reasoning on MATH500 and AIME25, and assess tool-use generalization on BFCL v4 Patil et al. (2025) (last updated: 2025-11-03) using the official evaluation scripts. Result are evaluated on latest BFCL V4. As a result, our reported numbers may differ from those reported by prior baselines evaluated on earlier versions of the benchmark. We report pass@1, averaged over eight independent runs to reduce variance. Additional training details and learning curves are provided in Appendix C.

Baselines.

We compare against a step-level process reward (PRM) baseline that assigns rewards directly to individual reasoning steps using the same LLM-based judge, without mid-level skill abstraction. We further include strong recent baselines for mathematical reasoning, including ReST Lin et al. (2025), EGPO Hao et al. (2025), and NPR Wu et al. (2025), following their official implementations.

5 Main Result

Table 1 summarizes the main results on mathematical reasoning and general tool-use benchmarks. Overall, our method consistently outperforms prior approaches across both mathematical reasoning and tool-use settings, demonstrating its effectiveness beyond a single task domain. On Qwen3-4B-Instruct-2507, our approach achieves a new best performance on MATH benchmarks, improving MATH500 accuracy from 92.3 (PRM) and 90.2 (EGPO) to 95.8, and AIME25 accuracy from 51.7 (PRM) to 63.3. Notably, these gains in mathematical reasoning do not come at the cost of tool-use capability: on BFCL, our method attains the highest overall score of 51.3, outperforming strong baselines such as EGPO (48.3) and PRM (44.6), with consistent improvements across both single-step and multi-step tool-use scenarios.

In addition, we observe that even a simple step-level PRM baseline remains competitive compared to more complex training schemes. For example, PRM already yields substantial gains over the base model on both MATH500 (from 89.1 to 92.3) and BFCL Overall (from 33.0 to 44.6) for Qwen3. However, our method further improves upon PRM by a large margin across all evaluated settings, including a +3.5 gain on MATH500 and a +6.7 gain on BFCL Overall. A similar trend holds for LLaMA 3.2-3B-Instruct, where our approach improves MATH500 accuracy from 48.3 (PRM) to 63.4 and BFCL Overall from 24.8 to 30.8. These results suggest that while PRM provides a strong and robust baseline, our prototype-conditioned reward formulation yields more consistent and transferable improvements across reasoning and tool-use tasks.

6 Research Questions and Ablation Studies

6.1 RQ1: Does Mid-Level Execution Improvement Lead to Emergent High-Level Planning Ability?

A central question in this work is whether improving mid-level reasoning abilities can translate into gains in high-level planning. While our training directly optimizes mid-level behavior via skill-conditioned rewards, it does not explicitly supervise high-level plan generation.

Structural training dynamics.

To study whether mid-level improvements translate into high-level gains, we track structural training dynamics at the subgoal and plan level throughout training, without relying on token-type annotation.

Mid-level execution is evaluated by both subgoal success and reliability. For each subgoal, we perform multiple independent rollouts and report Mid-level Success () as the macro-averaged completion rate over 64 trials. To capture execution stability, we additionally report Mid-level Uncertainty (), which measures the variability of outcomes across repeated rollouts, with lower values indicating more consistent execution.

High-level ability (HighLvl).

We measure high-level planning ability via execution-verified plan selection. For each task , we collect a set of candidate subgoal sequences (plans) and determine their viability through empirical execution. We define the model’s preference score for a plan as its length-normalized log-probability:

| (1) |

The HighLvl metric measures the fraction of viable–non-viable plan pairs for which the viable plan is ranked above the non-viable plan according to , which is equivalent to an AUC-style plan discrimination score.

To bridge mid-level execution and high-level plan selection, we additionally track plan separability (), a structural signal that quantifies how distinctly viable and non-viable subgoal sequences can be distinguished based on their empirical execution outcomes. When mid-level execution is unstable, different plans often fail for unrelated reasons, resulting in overlapping success distributions and low separability. As execution becomes more reliable, successful and unsuccessful plans diverge more clearly, increasing and enabling more effective plan-level discrimination.

Intuitively, as mid-level execution becomes more reliable and less variable, the empirical success distributions of viable and non-viable plans become increasingly separable. This sharpened distinction facilitates more reliable plan selection, leading to improvements in even without explicit supervision at the planning level. Full metric definitions, labeling thresholds, execution protocols, and the formal definition of are provided in Appendix E. For tabular reporting, we aggregate math performance by macro-averaging results on MATH500 and AIME25, as our goal here is to highlight cross-domain structural trends rather than dataset-specific effects.

Summary.

Although our training explicitly targets mid-level execution via skill-conditioned rewards, the resulting improvements are not confined to this level. As shown in Fig. 3, stabilization of mid-level execution precedes a monotonic increase in plan separability and a delayed but consistent rise in high-level plan selection ability, despite the absence of direct planning supervision. Table 2 corroborates this trend across models and domains, where gains in mid-level success are consistently accompanied by improvements in high-level ability. Together, these results indicate that improving mid-level execution reliability can induce emergent gains in high-level planning through enhanced structural separability rather than isolated local optimization.

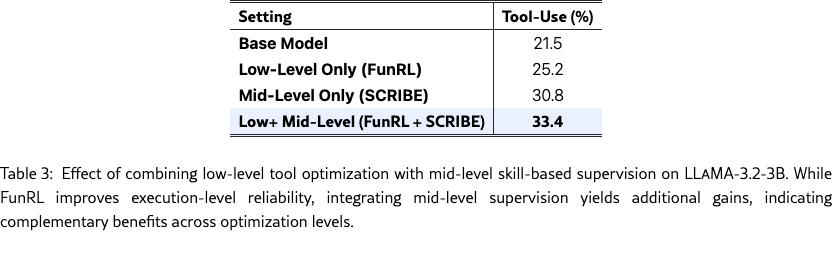

6.2 Can Mid-Level Skill Supervision Complement Low-Level Tool Optimization?

Most existing approaches to tool-augmented reasoning focus on improving low-level execution, such as increasing the reliability of tool invocation, argument formatting, or result parsing. These methods primarily operate at the level of individual tool calls and aim to reduce execution failures. In contrast, our approach targets mid-level skill execution by providing structured, skill-conditioned supervision over reusable tool-using behaviors. An important open question is whether improvements at these two levels are complementary, or whether gains from mid-level supervision diminish once low-level execution is sufficiently optimized.

To study this interaction, we combine our method with a representative low-level tool optimization approach. Specifically, we adopt FunRL Hao et al. (2025), a reinforcement learning method designed to improve function-calling reliability and argument correctness at the execution level. We train FunRL directly on the LLaMA-3.2-3B backbone to obtain a backbone-aligned low-level baseline, ensuring a controlled comparison without confounding architectural differences.

We compare four settings: the base model, a low-level optimized model trained with FunRL alone, a model trained with mid-level skill supervision alone, and a combined setting that integrates both. This design allows us to isolate the individual contributions of low- and mid-level optimization, and to assess whether mid-level supervision provides additive benefits beyond improved low-level execution.

Conclusion.

Low-level tool optimization and mid-level skill supervision act on distinct and non-conflicting aspects of tool-augmented reasoning. While FunRL improves execution-level reliability (21.525.2) and mid-level supervision independently yields larger gains (21.530.8), their combination leads to further improvements (25.233.4). These results indicate an additive and complementary relationship, where mid-level supervision augments rather than interferes with low-level optimization.

6.3 Ablation on Reward Weighting.

We study the effect of balancing process-level and outcome-level rewards. Specifically, we vary the weight of the process reward , with the outcome reward weight set to . All other training settings are kept fixed. Performance is evaluated on MATH500, AIME25, and BFCL v4 (Overall). Table 4 shows that the choice of reward weighting substantially affects both mathematical reasoning and tool-use performance. In particular, assigning a moderate weight to the process-level reward () achieves the best overall trade-off across MATH500, AIME25, and BFCL v4, whereas excessive emphasis on either intermediate or final rewards leads to performance degradation.

7 Conclusion

We introduced SCRIBE, a framework that enhances tool-augmented reasoning by intervening at a novel mid-level abstraction. By anchoring process rewards in a library of Skill Prototypes, SCRIBE transforms subjective LLM judging into grounded, diagnostic verification. Our results demonstrate state-of-the-art performance, notably improving the AIME25 score of a 4B model from 43.3% to 63.3% and doubling success rates in complex multi-turn tool use.

Beyond performance, our analysis of training dynamics characterizes a co-evolutionary principle: mid-level skill mastery acts as a necessary precursor to the emergence of strategic high-level planning. We further show that SCRIBE is highly additive, complementing low-level tool optimizations to yield superior synergistic effects. Future work will explore more autonomous ways to evolve skill libraries in real-time to handle open-domain tasks. Additionally, we aim to investigate how multi-level hierarchical supervision can be unified into a single objective to further enhance the strategic depth of autonomous agents.

8 Limitations

Although our approach yields consistent improvements on mathematical reasoning and tool-use benchmarks, several limitations remain. First, our experiments focus on small- to mid-sized instruction-tuned models; it is unclear how the proposed skill-conditioned supervision scales to substantially larger architectures or to models trained with different post-training pipelines. Second, the construction of skill prototypes and routing relies on clustering heuristics and judge-annotated data, which may introduce biases or limit adaptability in domains with highly diverse or ill-defined skill boundaries. Finally, our evaluation primarily targets structured reasoning and tool-use tasks; the effectiveness of the approach for open-ended generation or non-instrumental reasoning remains an open question.

9 Ethics

This work relies on publicly available datasets and uses an LLM-based judge accessed via the OpenAI API for reward evaluation OpenAI (2024). We do not access, attempt to access, or infer any proprietary training data or internal components of the underlying models. All experiments are conducted using standard model inference and optimization procedures, without collecting or processing personal or sensitive user data.

Risks

The datasets used in our experiments are sourced from publicly available benchmarks and may contain unintended biases, errors, or harmful language. While our method aims to improve the consistency of reward signals during training, it could potentially amplify biases present in the judge or training data if deployed without additional safeguards. We also use GPT5 to assist with minor grammatical corrections in this paper.

References

- Toolrm: outcome reward models for tool-calling large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.11963. Cited by: §2.2.

- Process reward models for llm agents: practical framework and directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.10325. Cited by: §2.2.

- Plan-seq-learn: language model guided rl for solving long horizon robotics tasks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2405.01534. Cited by: §2.3.

- Tool-star: empowering llm-brained multi-tool reasoner via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.16410. Cited by: §2.1.

- ToRA: a tool-integrated reasoning agent for mathematical problem solving. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §2.1.

- Deepseek-r1: incentivizing reasoning capability in llms via reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.12948. Cited by: §2.1.

- Reasoning through exploration: a reinforcement learning framework for robust function calling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2508.05118. Cited by: §4, §6.2.

- Memorization over reasoning? exposing and mitigating verbatim memorization in large language models’ character understanding evaluation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2412.14368. Cited by: §2.1.

- DRP: distilled reasoning pruning with skill-aware step decomposition for efficient large reasoning models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2505.13975. Cited by: §2.3.

- Process reward models that think. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.16828. Cited by: §1.

- From generation to judgment: opportunities and challenges of llm-as-a-judge. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 2757–2791. Cited by: §1, §2.2.

- One model to critique them all: rewarding agentic tool-use via efficient reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.26167. Cited by: §2.1.

- FAEDKV: infinite-window fourier transform for unbiased kv cache compression. External Links: 2507.20030, Link Cited by: §2.1.

- MARIO: math reasoning with code interpreter output-a reproducible pipeline. CoRR. Cited by: §2.1.

- Let’s verify step by step. In The Twelfth International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §2.2.

- ResT: reshaping token-level policy gradients for tool-use large language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.21826. Cited by: §4.

- Toolace: winning the points of llm function calling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2409.00920. Cited by: §1, §4.

- Understanding r1-zero-like training: a critical perspective. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.20783. Cited by: §2.1.

- OpenAI api documentation. Note: https://platform.openai.com/docsAccessed via official OpenAI API Cited by: §9.

- The berkeley function calling leaderboard (bfcl): from tool use to agentic evaluation of large language models. In Forty-second International Conference on Machine Learning, Cited by: §4.

- Toolrl: reward is all tool learning needs. arXiv preprint arXiv:2504.13958. Cited by: §1, §1, §2.1.

- Toolformer: language models can teach themselves to use tools. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36, pp. 68539–68551. Cited by: §2.1.

- Rewarding progress: scaling automated process verifiers for llm reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2410.08146. Cited by: §2.2.

- Skill-based model-based reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2207.07560. Cited by: §2.3.

- Atom of thoughts for markov llm test-time scaling. arXiv preprint arXiv:2502.12018. Cited by: §2.3.

- MathCoder: seamless code integration in llms for enhanced mathematical reasoning. In 12th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2024), Cited by: §2.1.

- Native parallel reasoner: reasoning in parallelism via self-distilled reinforcement learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2512.07461. Cited by: §4.

- Can atomic step decomposition enhance the self-structured reasoning of multimodal large models?. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.06252. Cited by: §2.3.

- Learning how to use tools, not just when: pattern-aware tool-integrated reasoning. In The 5th Workshop on Mathematical Reasoning and AI at NeurIPS 2025, Cited by: §2.1.

- Simpletir: end-to-end reinforcement learning for multi-turn tool-integrated reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.02479. Cited by: §1.

- ReAct: synergizing reasoning and acting in language models. In The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §1, §2.1.

- Dapo: an open-source llm reinforcement learning system at scale. arXiv preprint arXiv:2503.14476. Cited by: §2.1.

- Demystifying reinforcement learning in agentic reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.11701. Cited by: §1.

- The landscape of agentic reinforcement learning for llms: a survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2509.02547. Cited by: §1.

- Find your optimal teacher: personalized data synthesis via router-guided multi-teacher distillation. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.10925. Cited by: §2.1.

- The lessons of developing process reward models in mathematical reasoning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2501.07301. Cited by: §1.

- One token to fool llm-as-a-judge. arXiv preprint arXiv:2507.08794. Cited by: §2.2.

Appendix A Reward Calibration and Consistency Analysis

A.1 Prompt Variants

Prompt Variant M1 (Narrative Decomposition).

You are given a complete solution to a math problem.

Analyze the solution and identify the key intermediate subgoals that are required to reach the final answer.

For each subgoal, briefly describe the mathematical objective being achieved and the primary reasoning skill involved.

Focus on meaningful reasoning stages rather than low-level algebraic steps.

The subgoals should be ordered and together sufficient to solve the problem.

(Example output omitted.)

Prompt Variant M2 (Coverage-Constrained Segmentation).

You will receive a solution trajectory for a math problem.

Segment the entire solution into a sequence of subgoals such that every part of the trajectory belongs to exactly one subgoal.

Each subgoal should correspond to a coherent reasoning objective.

For each subgoal, identify the dominant mathematical skill applied.

Ensure no overlap or omission across subgoals.

(Example output omitted.)

Results.

Across math problems, both prompt variants recover highly consistent subgoal structures. The ordering and skill attribution of subgoals largely agree with those produced by the main prompt, with high rank-level agreement in reward scores. This indicates that subgoal extraction and subsequent reward evaluation are not sensitive to prompt phrasing.

Prompt Variant T1 (Intent-Oriented Decomposition).

You are given a multi-turn, tool-using interaction. Identify the sequence of subgoals that the system completes in order to satisfy the user’s request. Each subgoal should describe a concrete intent or intermediate objective and the primary capability required to achieve it. Subgoals may span multiple turns and should reflect mid-level planning rather than surface actions.

(Example output omitted.)

Prompt Variant T2 (Failure-Aware Segmentation).

Given a tool-using conversation trajectory, segment it into subgoals such that the entire interaction is covered. If the trajectory includes partial failures, corrections, or fallback behaviors, include them as explicit subgoals. For each subgoal, identify the dominant tool-use or reasoning skill involved.

(Example output omitted.)

Results.

For tool-using tasks, both prompt variants produce subgoal partitions that closely match the main prompt. Reward scores assigned based on these subgoals remain stable across prompts, with only minor variations in boundary placement for a small number of tool-related steps. Overall, the judge exhibits robust agreement across prompt formulations.

A.2 Subgoal-Level Reward Calibration

The LLM-based judge assigns discrete reward scores in to each subgoal. To improve alignment between reward magnitude and actual correctness, we calibrate rewards using empirical subgoal-level outcome statistics.

For each subgoal type, we estimate the empirical success rate of final task completion conditioned on the assigned reward score. If a lower raw reward (e.g., 2) corresponds to a success rate comparable to a higher reward (e.g., 3), the reward is calibrated upward. Conversely, rewards that systematically overestimate correctness are adjusted downward. Calibration is implemented via a subgoal-specific lookup table, preserving relative ordering while improving reward validity.

Human Agreement.

We uniformly sample 100 subgoal instances across all reward levels and manually verify whether the assigned rewards reasonably reflect subgoal quality. No systematic disagreement is observed, providing a sanity check that the reward scores align with human judgment.

A.3 Reward Consistency via Anchor Subgoals

To assess reward consistency over time, we select 20 fixed anchor subgoals for each task type. Each anchor subgoal is re-evaluated five times at different checkpoints during training.

The assigned rewards are highly stable. Only two anchor instances in tool-use tasks receive slightly different scores across evaluations, while all remaining anchor subgoals retain identical rewards. This suggests that the judge’s evaluation criteria remain consistent over time without noticeable drift.

Appendix B Router Evaluation

We evaluate the Router on held-out judge-annotated trajectories to assess its ability to recover mid-level reasoning structure. The annotated data are split into training and test sets with a 9:1 ratio. Evaluation is performed on the test split and focuses on three aspects: step segmentation, skill prediction, and Skill Prototype retrieval.

The Router takes as input a problem and its corresponding raw reasoning trajectory, and outputs an ordered sequence of subgoal, skill, step tuples together with the associated Skill Prototype. All reported metrics are computed by comparing the Router outputs against judge-provided annotations.

Step Segmentation Accuracy.

We evaluate step prediction using span-level exact match (EM). A predicted step is considered correct if its start and end positions exactly match the annotated step span in the original trajectory. This metric directly measures whether the Router correctly partitions the trajectory into non-overlapping reasoning segments.

Skill Prediction Accuracy.

For each predicted subgoal, we evaluate whether the associated skill label matches the annotated skill. We report classification accuracy over all subgoals in the test set.

Skill Prototype Retrieval Accuracy.

We evaluate whether each subgoal is routed to the correct Skill Prototype. A prediction is considered correct if the retrieved prototype matches the annotated prototype. This metric reflects the Router’s effectiveness in providing correct skill-level context for reward evaluation.

Appendix C Additional Training Details

We provide additional details on GRPO training and stability diagnostics to facilitate reproducibility.

GRPO Configuration.

The student model is optimized using GRPO with skill-conditioned process-level rewards. For mathematical reasoning, we sample 8 rollouts per problem over 10k training problems. We include a KL regularization term to constrain policy updates and an entropy bonus to encourage exploration. Reward shaping is applied to normalize process-level scores. Unless otherwise specified, the same optimization settings are used across all methods.

Optimization Settings.

We use a fixed learning rate and batch size throughout training, with a local batch size of 128. All hyperparameters are selected from standard ranges used in prior GRPO and RLHF-style training and are kept constant across baselines.

Training Stability.

To monitor training stability, we track reward statistics over time, including mean reward and reward variance. We observe no evidence of reward collapse during training.

Appendix D Prompts for Subgoal and step decomposition

We use structured prompts to decompose each problem or trajectory into mid-level subgoals and associated skills, which serve as the basis for our skill-aware supervision and analysis.

Appendix E Execution-Verified Plan Selection and Structural Metrics

Mid-level success and uncertainty.

For each subgoal , we sample independent rollouts and define the subgoal success rate as

| (2) |

where in all experiments. We report the macro-average .

To quantify execution reliability, we define the mid-level uncertainty for subgoal as

| (3) |

and report its macro-average . This measure captures the variability of execution outcomes across repeated rollouts under a fixed subgoal specification.

Candidate plan construction and execution.

For each task instance , we collect a candidate plan set consisting of subgoal sequences extracted from prior rollouts. These candidate plans are held fixed across training checkpoints. Each plan is executed for independent trials, yielding an empirical success rate

| (4) |

with in all experiments.

Plan viability labeling.

Based on empirical success rates, plans are partitioned into viable and non-viable sets. A plan is labeled viable if and non-viable if ; intermediate cases are discarded. Unless otherwise specified, we use and . We verify that alternative rank-based labeling strategies (e.g., top- vs. bottom- plans) yield consistent qualitative trends.

Execution-verified plan selection

Let and denote the sets of empirically viable and non-viable plans for task , respectively. Given a preference score , we define

| (5) |

This metric is equivalent to the AUC of a binary classifier that ranks viable versus non-viable plans using .

Plan separability.

To analyze the structural conditions under which high-level plan selection improves, we additionally compute plan separability (). Unlike , which depends on model preferences, is defined purely in terms of empirical execution outcomes. Specifically, for each task , we compute the gap between the mean execution success rates of viable and non-viable plans:

| (6) |

A larger value indicates that successful and unsuccessful plans are more clearly separated in execution outcome space, reflecting a structural signal induced by improved execution reliability.

Evaluation scale.

For mid-level evaluation, we sample subgoals extracted from a fixed subset of problems in each dataset. Specifically, we evaluate on problems from MATH500 and problems from AIME25, yielding an average of approximately subgoals per problem. Each subgoal is evaluated with independent rollouts.

For high-level evaluation, candidate plan sets are constructed from the same problem subset. For each problem, we collect candidate subgoal sequences from prior rollouts (typically –). Each candidate plan is executed for trials to estimate empirical viability. High-level ability and plan separability are then computed by aggregating execution-verified statistics across all evaluated problems.

Appendix F Cluster and Prototype examples

Math Prototype

Tool use Prototype