Accelerating Scientific Discovery with Autonomous Goal-evolving Agents

Abstract

There has been unprecedented interest in developing agents that expand the boundary of scientific discovery, primarily by optimizing quantitative objective functions specified by scientists. However, for grand challenges in science , these objectives are only imperfect proxies. We argue that automating objective function design is a central, yet unmet requirement for scientific discovery agents. In this work, we introduce the Scientific Autonomous Goal-evolving Agent (SAGA) to amend this challenge. SAGA employs a bi-level architecture in which an outer loop of LLM agents analyzes optimization outcomes, proposes new objectives, and converts them into computable scoring functions, while an inner loop performs solution optimization under the current objectives. This bi-level design enables systematic exploration of the space of objectives and their trade-offs, rather than treating them as fixed inputs. We demonstrate the framework through a broad spectrum of applications, including antibiotic design, inorganic materials design, functional DNA sequence design, and chemical process design, showing that automating objective formulation can substantially improve the effectiveness of scientific discovery agents.

Yuanqi Du1,*,†, Botao Yu2,*, Tianyu Liu3,*, Tony Shen4,*, Junwu Chen5,*, Jan G. Rittig5,*, Kunyang Sun6,*,

Yikun Zhang7,*, Zhangde Song8, Bo Zhou9, Cassandra Masschelein5, Yingze Wang6, Haorui Wang10,

Haojun Jia8, Chao Zhang10, Hongyu Zhao3, Martin Ester4, Teresa Head-Gordon6,†, Carla P. Gomes1,†,

Huan Sun2,†, Chenru Duan8,†, Philippe Schwaller5,†, Wengong Jin7,11,†

1Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA 2The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA 3Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

4Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada 5École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

6University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA 7Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

8Deep Principle, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China 9University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

10Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA 11Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA

*These authors contribute equally

†Correspondence to: yd392@cornell.edu, thg@berkeley.edu, gomes@cs.cornell.edu, sun.397@osu.edu, duanchenru@gmail.com, philippe.schwaller@epfl.ch, w.jin@northeastern.edu

December 25, 2025

1 Introduction

Scientific discovery has been driven by human ingenuity through iterations of hypothesis, experimentation, and observation, but is increasingly bottlenecked by the vast space of potential solutions to explore and the high cost of experimental validation. Recent advances in artificial intelligence (AI) agents based on large language models (LLMs) offer promising approaches to address these bottlenecks and accelerate scientific discovery. Leveraging massive pretrained knowledge and general capabilities for information collection and reasoning, these AI agents can efficiently navigate large solution spaces and reduce experimental costs by automating key aspects of the research process. For example, pipeline automation agents [? ? ] streamline specialized data analysis workflows, reducing the manual effort required for routine experimental processes. AI Scientist agents [? ? ? ? ? ] tackle the exploration challenge by autonomously generating and evaluating novel hypotheses (e.g., the relationship between a certain mutation and a certain disease) through integrated literature search, data analysis, and academic writing capabilities.

Our work embarks on a different and more ambitious goal in scientific discovery: building agents to discover new solutions to complex scientific challenges, such as proofs for conjectures, faster algorithms, better therapeutic molecules, and functional materials. This problem is uniquely challenging due to the "creativity" and "novelty" required and the infinite combinatorial search space for potential solutions. Previous work has sought to address these challenges by developing optimization models that automatically find solutions maximizing a manually defined set of quantitative objectives, such as drug efficacy, protein expression, and material stability. These approaches, ranging from traditional generative models to more recent LLM-based methods, have demonstrated the ability to efficiently optimize against fixed objectives in domains including drug design [? ], algorithm discovery [? ], and materials design [? ].

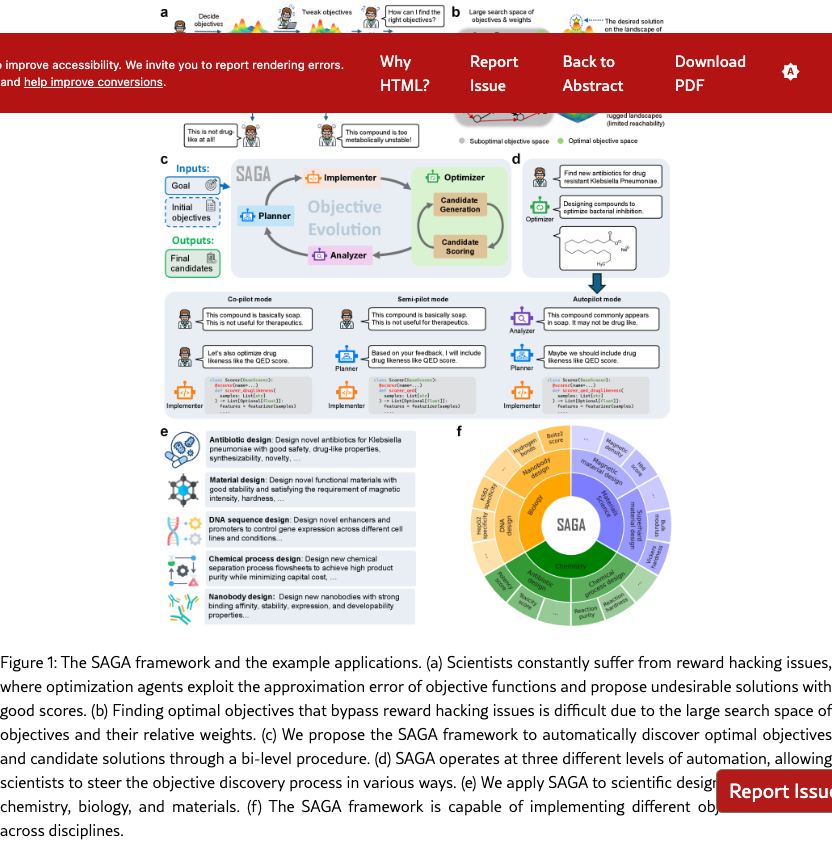

However, these optimization models operate under a critical assumption: that the right set of objective functions is known upfront. In practice, this assumption rarely holds. Just as scientific discovery requires iterations of hypothesis, experimentation, and observation, determining the appropriate objectives for a discovery task is itself an iterative search process. Scientists must constantly tweak objectives based on intermediate results, domain knowledge, and practical constraints that emerge during exploration (Figure˜1(a)). This iterative refinement is particularly crucial in experimental disciplines such as drug discovery, materials design, and protein engineering, where many critical properties can only be approximated through predictive models. Without this evolving process, the discovery suffers from reward hacking issues [? ]: they exploit gaps between models and reality, producing solutions that maximize predicted scores while missing important practical considerations that experts would recognize. The search space for objectives and their relative weights is itself combinatorially large (Figure˜1(b)), making it extremely difficult to specify the right objectives from the outset. As a result, while existing optimization models can solve the low-level optimization problem efficiently, scientific discovery remains bottlenecked by the high-level objective search process that relies on manual trial-and-error.

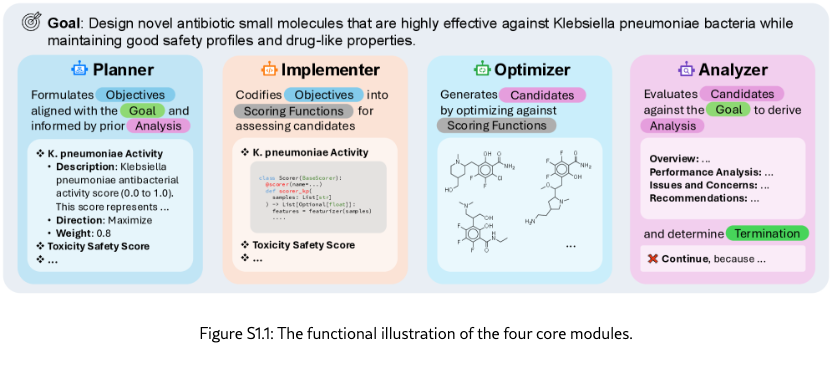

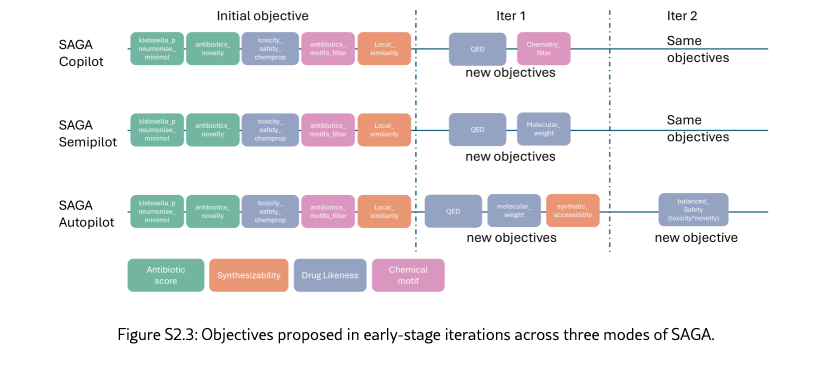

In this work, we introduce SAGA as our first concrete step toward automating this iterative objective evolving process. SAGA is designed to navigate the combinatorial search space of objectives by integrating high-level objective planning in the outer loop with low-level optimization in the inner loop (Figure˜1(c)). The outer loop comprises four agentic modules: a planner that proposes new objectives based on the task goal and current progress, an implementer that converts proposed objectives into executable scoring functions, an optimizer that searches for candidate solutions maximizing the specified objectives, and an analyzer that examines the optimization results and identifies areas for improvement. Within the optimizer module, an inner loop employs any optimization methods (e.g., genetic algorithms or reinforcement learning) to iteratively evolve candidate solutions toward the current objectives. Importantly, SAGA is a flexible framework supporting different levels of human involvement. It offers three modes (Figure˜1(d)): (1) co-pilot mode, where scientists collaborate with both the planner and analyzer to reflect on results and determine new objectives; (2) semi-pilot mode, where scientists provide feedback only to the analyzer; and (3) autopilot mode, where both analysis and planning are fully automated. This design allows scientists to interact with SAGA in ways that best suit their expertise and preferences.

SAGA is a generalist scientific discovery agentic framework with demonstrated success across multiple scientific domains, from chemistry and biology to materials science (Figure˜1(e)-(f)). In antibiotic design, SAGA successfully discovered new antibiotics with high predicted potency against Klebsiella pneumoniae while satisfying complex physicochemical constraints. In inorganic materials design, SAGA designed permanent magnets with low supply chain risk and superhard materials for precision cutting, with properties validated by Density Functional Theory (DFT) calculations. In functional DNA sequence design, SAGA proposed high-quality cell-type-specific enhancers for the HepG2 cell line, with nearly 50% improvement over the best baseline. Lastly, SAGA demonstrated success in automating the design of chemical process flowsheets from scratch. In summary, these results highlight the broad applicability of SAGA in many disciplines and the value of adaptive objective function design in scientific discovery agents.

2 Results

2.1 SAGA for Antibiotic Design

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is rapidly eroding our ability to treat common Gram-negative infections, one of which is Klebsiella pneumoniae (K. pneumoniae), a critical priority pathogen ranked by the World Health Organization (WHO) [? ? ]. However, designing novel inhibitors for Gram-negative bacteria is notoriously difficult, as optimization agents suffer from generating chemically unreasonable compounds that hack the given objectives [? ]. To address this challenge, we use SAGA to design novel K. pneumoniae inhibitors. Rather than relying on a static scoring function that attempts to encode every rule upfront, SAGA begins with only primary biological objectives for maximizing potency and minimizing toxicity, along with a constraint to avoid existing scaffolds. From this foundation, SAGA dynamically constructs a suite of auxiliary objectives that steer the generative process toward realistic chemical space at all three levels of automation. This strategy allows SAGA to learn the specific constraints of the Gram-negative landscape in an interpretable, iterative manner. Ultimately, SAGA produces more valid candidates that satisfy rigorous external evaluations and align with scientists’ intuition.

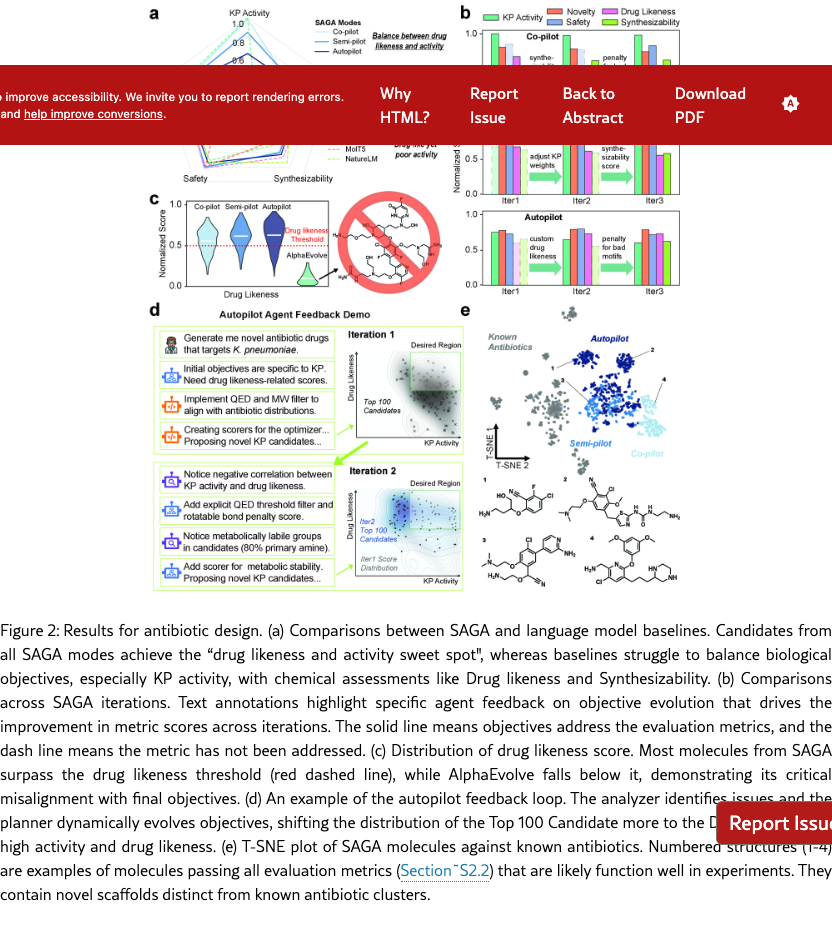

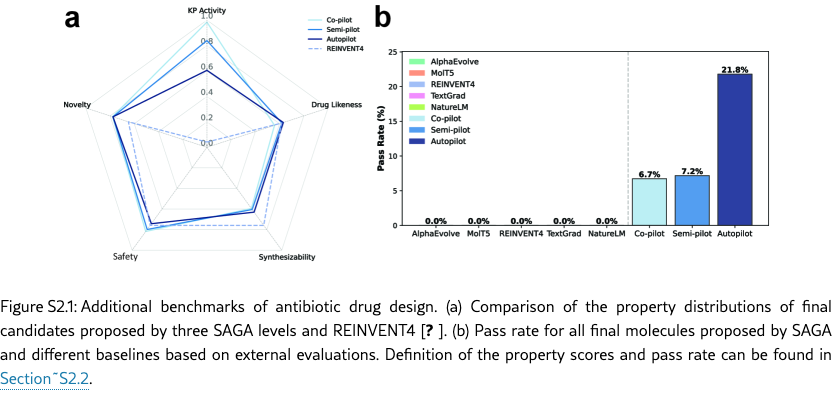

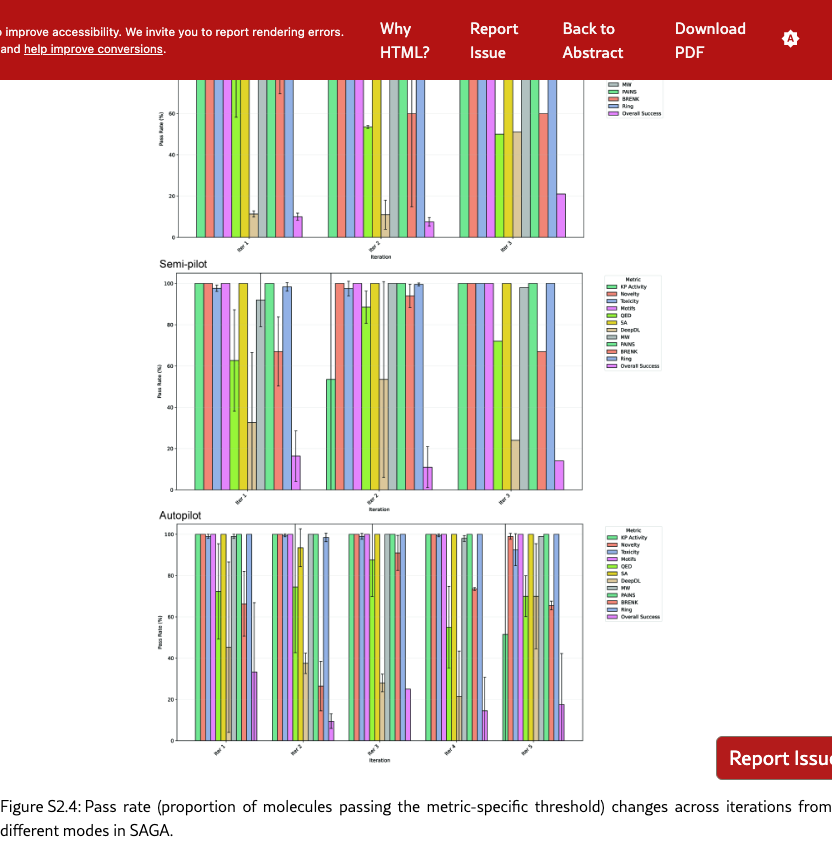

SAGA discovers computationally selective and chemically reasonable candidates. We run SAGA at all three levels of automation with the same prompt and primary biological objectives. SAGA then iterates at different levels of automation until optimization is complete. To evaluate the quality of proposed candidates, we selected three biological evaluations (KP Activity defined by the Antibiotic activity score, Novelty defined by the Novelty score, Safety defined by 1 - the Toxicity score) and two chemical evaluations (Drug likeness defined by the Quantitative estimate of drug likeness (QED) score, and Synthesizability defined by the Synthetical Accessibility (SA) score.) These scores are further elaborated in Section˜S2.2.

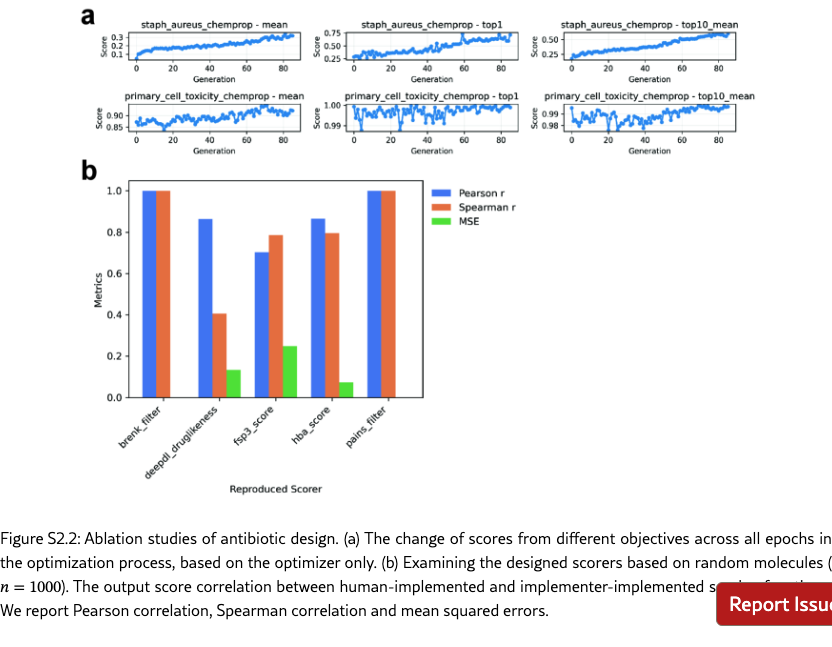

As illustrated in Figure˜2(a) and Figure˜S2.1(a), SAGA successfully balance the scores of both biological objectives and standard medicinal chemistry filters, discovery drug-like molecules with high predicted activity. Consequently, as shown in Figure˜S2.1(b), SAGA achieves a significantly higher percentage of candidates passing all evaluations (detailed in Section˜S2.2) compared to state-of-the-art language model baselines. In contrast to SAGA, these baselines exhibit distinct failure modes. Several language models struggle to overcome the optimization difficulty of the KP activity score alone, resulting in chemically valid but inactive molecules. Conversely, AlphaEvolve, which does not have the capacity to dynamically evolve objectives, achieves high KP activity but suffers a catastrophic drop in medicinal chemistry quality. As shown in Figure˜2(c), while SAGA candidates consistently score above the Drug likeness Threshold, AlphaEvolve’s population distribution falls almost entirely below it, designing unrealistically large and undrug-like molecules. This observation confirms that, without dynamic auxiliary objectives, language models either fail to optimize the primary biological goal or, like AlphaEvolve, exploit the scoring function to propose active but chemically invalid structures. SAGA, on the other hand, successfully aligns with the desired distribution of realistic drug candidates, producing the most promising candidates.

SAGA can effectively analyze, propose, and implement informative and necessary objectives across different levels of automation. To enable explainable and robust optimization, SAGA dynamically evolves its scoring functions, reorienting the trajectory to align with both the global K. pneumoniae optimization goals and chemical intuition. As illustrated in Figure˜2(b) and Section˜S6.1, the components from SAGA demonstrate context-awareness regarding the optimization landscape. While the co-pilot mode incorporates nuanced human feedback to address low synthesizability, the semi-pilot agent intelligently defers adding strict chemical constraints in early iterations to instead adjust weights and prioritize the optimization of the KP activity objective. In the autopilot mode, the analyzer agent provides chemical insights that anticipate expert concerns. As shown in Figure˜2(d) and Section˜S6.1, SAGA goes beyond individual molecular analysis and identifies population-level trends, such as “negative correlation between KP activity and drug likeness". Furthermore, it performs granular structural analysis to pinpoint specific over-represented metabolically labile groups, insights that typically require systematic review to uncover. In response, SAGA autonomously constructs filters and scorers that steer the generated population to the "Desired Region" of the physicochemical space, leading to a higher passing rate for external chemical motif alerts. Collectively, these examples demonstrate the practical utility of dynamic objective evolution in solving the hard, multi-objective optimization problem, generating final candidates that show more promises.

SAGA discovers computationally performant molecules with novel, synthetically accessible scaffolds distinct from existing antibiotics. A primary goal of de novo design is to discover potent, drug-like candidates that diverge from the existing antibiotics space. Therefore, after SAGA finishes optimization, we first filter all proposed candidates by applying a set of stringent evaluation cutoffs to select molecules with high probability of experimental success and then assess how similar they are to existing antibiotics. As shown in Figure˜2(e), the selected molecules occupy diverse regions distinct from the tight clusters of over 500 known antibiotics. Specific examples (Structures 1–4) further illustrate that, rather than only optimizing around one fixed scaffold, SAGA generalize the rules of bacterial inhibition to assemble novel backbone architectures and halobenzene cores. Crucially, despite this high degree of novelty, these antibiotic candidates are either directly purchasable, or have commercial analogs with high similarity, suggesting that they could serve as promising candidates for experimental validation in the next step.

2.2 SAGA for Inorganic Materials Design

The discovery of novel materials is critical for driving technological innovation across diverse fields, including catalysis, energy, electronics, and advanced manufacturing [? ? ? ? ? ? ]. Most material design tasks involve multiple objectives encompassing electronic, mechanical and physicochemical properties, as well as production costs [? ? ]. These design objectives are often intricately interrelated and may exhibit competitive or even conflicting trade-offs [? ? ? ]. Optimization with fixed objectives may overlook other important material properties or fail to refine optimization objectives based on deficiencies identified in proposed candidates. To address this challenge, we apply SAGA to design the desired novel materials for specific applications through iterative optimization with dynamic objectives. SAGA can guide LLMs to search materials with desired properties, iteratively analyzing and adjusting optimization objectives, while automatically programming scoring functions to evaluate the new objectives and provide feedback. We propose two design tasks to assess the SAGA’s effectiveness.

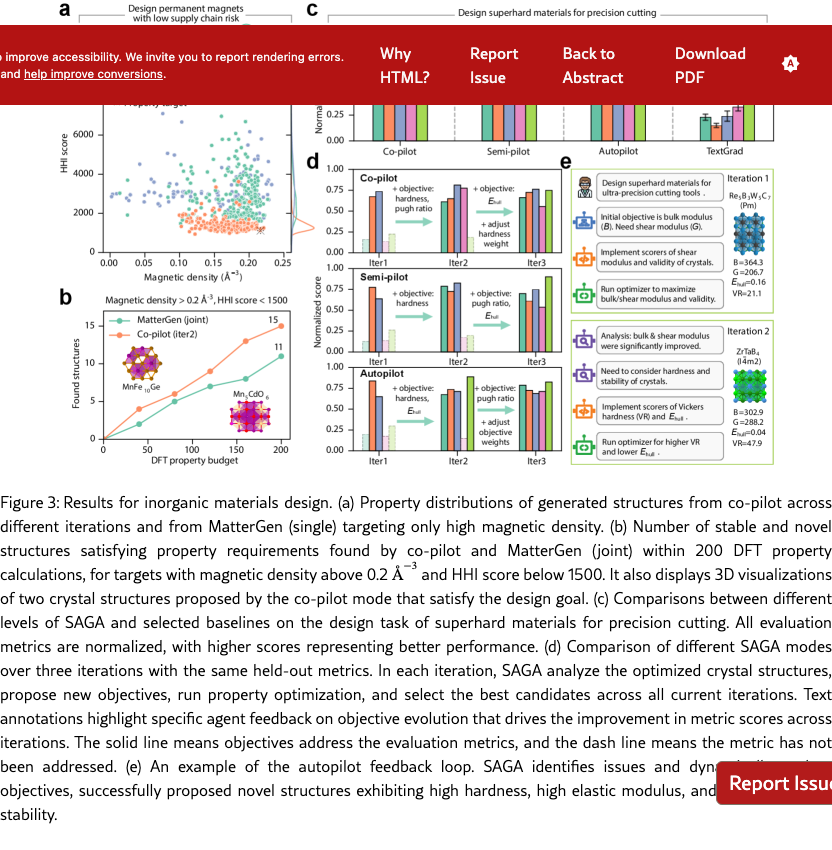

SAGA enables efficient magnet materials design. First, we evaluate SAGA on the task of designing permanent magnets with low supply chain risk, and compare against MatterGen [? ], one of the state-of-the-art generative models for inorganic materials design. In this task, two objectives are specified: magnetic density higher than 0.2 and Herfindahl–Hirschman index (HHI) score less than 1500, where a lower HHI score indicates lower supply chain risk and the absence of rare earth elements [? ? ]. The SAGA Co-pilot mode is deployed with iteratively refined objectives: maximizing magnetic density in the first iteration, followed by the addition of HHI score minimization in the second. Performance was compared against the MatterGen model that targets only high magnetic density (single) or both properties (joint) [? ]. As shown in Figure˜3(a), Co-pilot proposes crystal structures with high magnetic density after the first iteration, exhibiting a higher distribution density near the target value of 0.2 compared to MatterGen (single). However, these structures display a broad range of HHI scores, with over 80 % exceeding 2000. After the second iteration, Co-pilot successfully discovers crystal structures with both high magnetic density and low HHI scores. The majority of proposed structures exhibit magnetic density above 0.15 and HHI scores below 1500. This demonstrates that SAGA’s Co-pilot mode can continuously and iteratively optimize material properties with human feedback to accomplish multi-objective tasks. Moreover, within a computational budget of 200 DFT property evaluations (Figure˜3b), Co-pilot mode identify 15 novel and stable structures satisfying the desired properties, outperforming MatterGen (11 structures). These results demonstrate that SAGA can continuously optimize dynamic objectives, potentially outperforming specialized generative models that are constrained to fixed objectives.

SAGA enables efficient superhard materials design. Subsequently, we evaluate SAGA on the task of designing superhard materials for precision cutting and compare with an LLM-based optimization algorithm, TextGrad [? ], as MatterGen [? ] requires fine-tuning on large amounts of DFT-labeled data when switching tasks. This task involves more than three target material properties, whereas conventional methods that optimize with fixed targets may only achieve high scores on certain metrics but but ignore other important properties of the designed materials. As shown in Figure˜3(c), the crystal structures designed by three modes (co-pilot, semi-pilot, autopilot) achieve high scores on all metrics. Benefiting from iterative optimization and dynamic objective refinement, all SAGA modes successfully propose novel structures exhibiting high hardness, high elastic modulus, appropriate brittleness, and thermodynamic stability. In contrast, the TextGrad approach, which employs fixed optimization objectives, demonstrated moderate performance for energy above hull and Pugh ratio but achieved much lower scores for hardness and elastic modulus. These results demonstrate that SAGA’s iterative optimization and dynamic objective strategy are effective for complex multi-objective tasks. Furthermore, we analyze the crystal structures proposed by SAGA in the final iteration and found that the underlying patterns correlate with key factors for superhard material formation reported in experimental studies. More than 90 % of the proposed crystals contain light elements such as boron, carbon, nitrogen, and oxygen, aligning with experimental findings that light elements are essential for superhard materials because their small atomic radii enable short, directional covalent bonds with high electron density [? ? ]. In addition, over 75 % of the proposed crystals are transition metal carbides, nitrides, and borides. Correspondingly, experimental studies have demonstrated that the combination of light elements (boron, carbon, nitrogen) with electron-rich transition metals can form dense covalent networks and enhance material hardness [? ? ].

SAGA proposes reasonable and important objectives aligning with materials scientists. The co-pilot and semi-pilot modes incorporate human input into the agent’s decision-making process to review and refine candidate analyses and proposed objectives for subsequent iterations. As shown in Figure˜3(d), integration of human feedback enabled SAGA to consider additional relevant objectives across multiple iterations, resulting in comprehensive performance improvements of the designed materials. For instance, explicit prioritization of Vickers hardness, elastic modulus and Pugh ratio [? ? ], guided by expert input, led to substantial enhancement of the mechanical properties in proposed crystalline materials. The results demonstrate that SAGA can effectively integrate human feedback through adaptive objective formulation, improving the overall performance of proposed materials. Moreover, SAGA’s autopilot mode can analyze results and set objectives autonomously without human intervention. By analyzing materials proposed in the current iteration, autopilot mode can identify their weaknesses and adaptively refines objectives for iterative improvement. As illustrated in Figure˜3(d), autopilot mode can propose important optimization objectives for the design goal, similar to expert guidance. Autopilot achieves excellent overall performance comparable to co-pilot and semi-pilot across all five metrics, underscoring its remarkable intelligence and automation capabilities. Figure˜3e demonstrates that autopilot can correctly understand the design goal and analyze properties of proposed materials, subsequently proposing appropriate and highly relevant new objectives (e.g., Vickers hardness, Pugh ratio, and energy above hull) targeting mechanical performance and stability. For newly proposed objectives, SAGA implements property evaluators through web search and automated programming, leveraging publicly available pretrained models or empirical methods. Upon analyzing designed structures and determining that a particular objective has been sufficiently optimized, SAGA automatically adjusts the optimization weight for that objective. Specifically, SAGA employs scaling or truncation of material property values to prevent over-optimization of individual objectives while neglecting others. Overall, these results demonstrate that SAGA enables automated materials design with different levels of human intervention through dynamic iterative optimization.

2.3 SAGA for Functional DNA Sequence Design

Programmed, highly precise, and cell-type-specific enhancers and promoters are fundamental to the development of reporter constructs, genetic therapeutics, and gene replacement strategies [? ]. Such regulatory control is particularly important in HepG2, a human hepatocellular carcinoma cell line that retains key hepatic functions within a single cell type, including plasma protein synthesis and xenobiotic drug metabolism [? ]. Although enhancers play a central role in establishing cell-type-specific gene expression programs [? ], their rational design remains challenging due to the vast combinatorial space of possible functional DNA sequences. This task can be naturally formulated as an optimization problem with predefined oracle functions, such as DNA expression level predictor [? ]. However, optimizing solely against expression-based oracles often results in sequences that generalize poorly with respect to biologically relevant constraints, including transcription factor motif enrichment, sequence diversity, and DNA stability. To address these limitations, we apply SAGA to discover novel cell-type-specific enhancers while iteratively refining the optimization objectives. Here, SAGA framework is initialized using cell-type-specific expression measurements obtained from Massively Parallel Reporter Assays (MPRA) [? ] and performs optimization with respect to an initial set of objectives. Crucially, SAGA closes the design loop by systematically analyzing deficiencies in the designed sequences and adaptively modifying the objective functions to guide subsequent exploration. Through this iterative refinement process, SAGA converges toward a more comprehensive and biologically grounded objective set, yielding optimized enhancer candidates that better satisfy multifaceted design requirements.

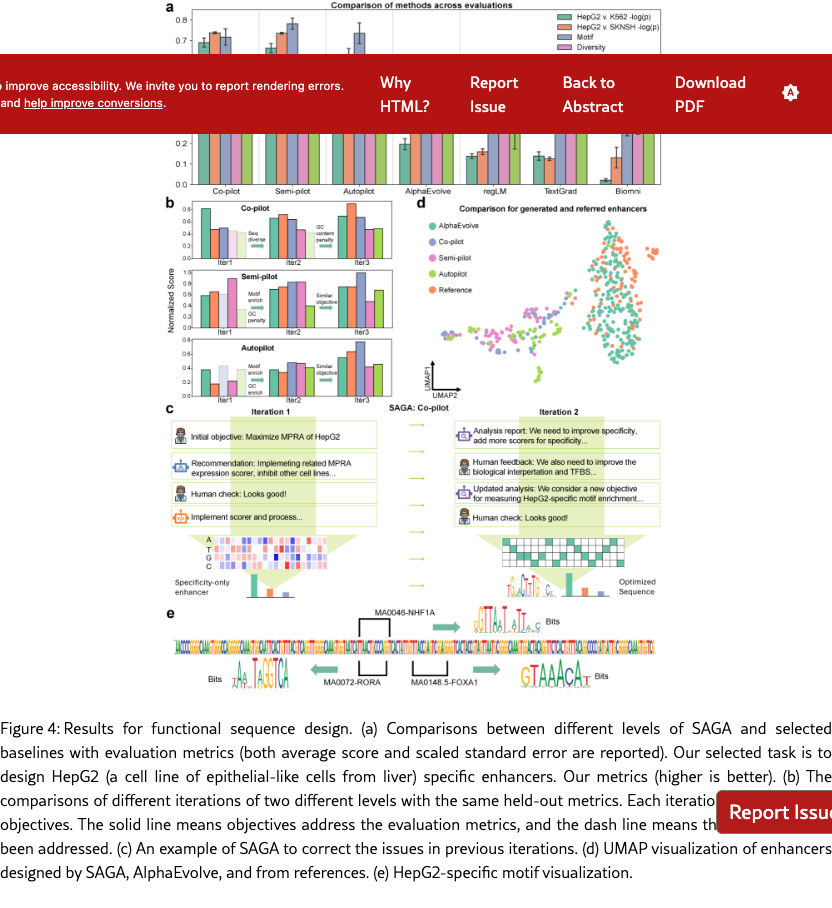

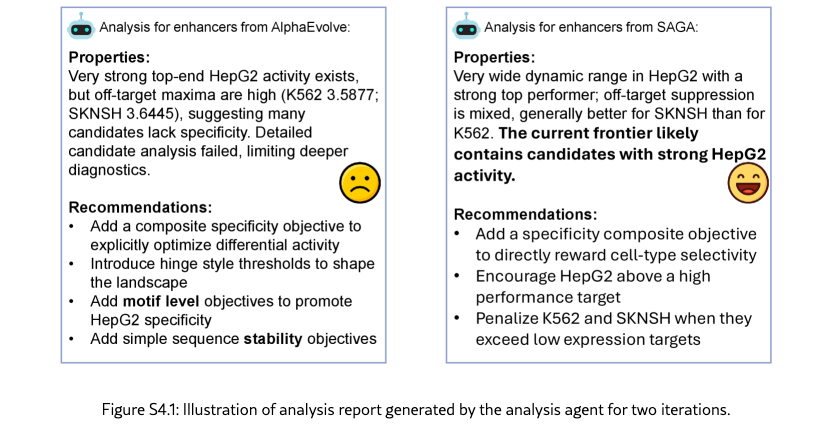

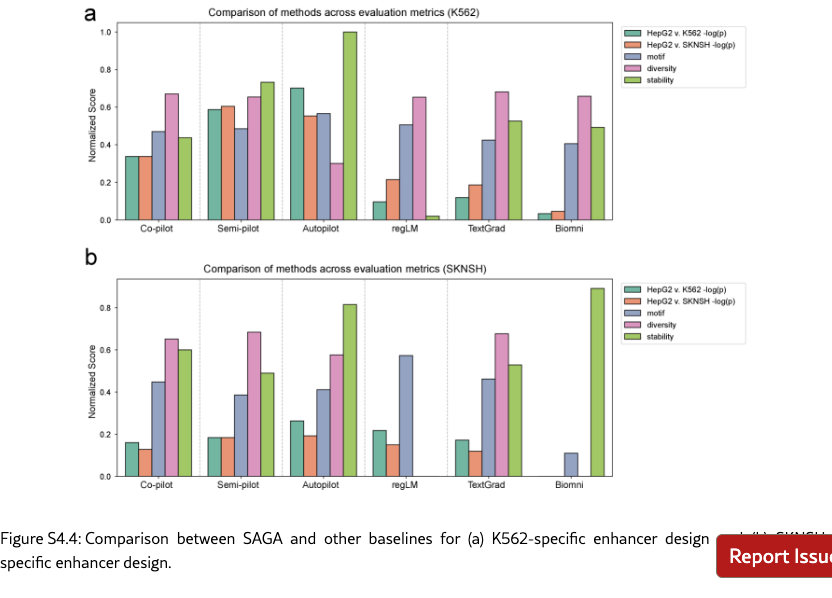

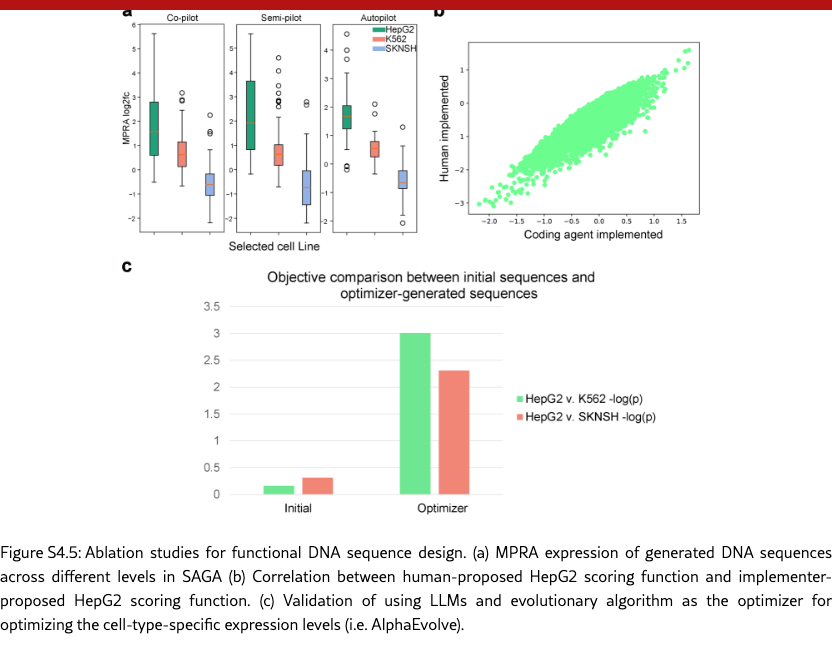

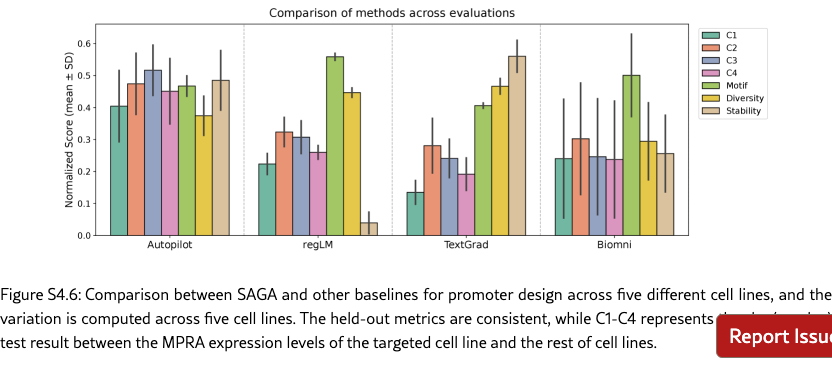

SAGA effectively discovers biologically plausible functional DNA sequences. We compare SAGA’s discovery capabilities by benchmarking it against established domain-specific models and AI agents [? ? ? ? ]. Figure˜4(a) reveals that our agents in different modes surpass selected baselines on metrics probing both statistical validity and biological function by 176.2% at most and 19.2% at least, based on the average comparison. Under controlled conditions where all baselines targeted the same objectives, our system exhibits marked improvements in MPRA specificity (by 48.0% at least), motif enrichment (by 47.9% at least), and sequence stability (by 1.7% at least). To further demonstrate the superiority of the multi-objective optimization method proposed by SAGA, we utilize the analyzer to examine the differences between enhancers produced by AlphaEvolve [? ] and SAGA. Figure˜S4.1 indicates that our designed enhancers exhibit obviously higher specificity and possess richer biological features compared to the former. These results suggest that SAGA effectively captures the complex interplay between statistical likelihood and biological constraints.

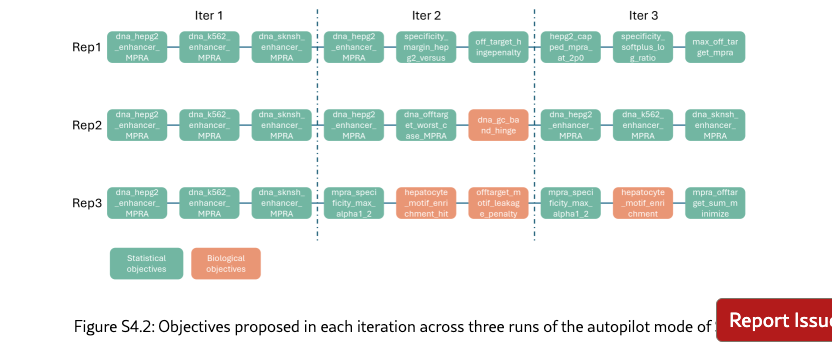

SAGA proposes reasonable and helpful objectives to assist human scientists for enhancer design. Co-pilot and Semi-pilot explicitly incorporate human intervention during the agent’s decision-making process to review, correct, and refine intermediate analyses and proposed objectives. As illustrated in Figure˜4(b), the inclusion of human feedback leads to marked improvements in biologically meaningful designed outcomes. For example, explicitly prioritizing transcription factor motif enrichment and sequence stability can be guided by expert input (Figure˜4(c) and SI S6.2), which results in enhanced biological validity of the designed sequences. Performance metrics and interaction logs further demonstrate that SAGA effectively integrates human guidance by adapting its objective formulation, particularly for biology-driven constraints. This collaborative human–AI refinement paradigm enables SAGA to achieve performance gains beyond those attainable through fully automated iterations alone. Our agent can also fully automatically design enhancers, which is corresponding to our Autopliot. Again, as shown in Figures 4(a) and (b), Autopliot achieves overall performance comparable to that obtained with human intervention, particularly with respect to HepG2 specificity and improvements in sequence diversity and stability. Moreover, Autopliot also consistently outperforms other fully automated AI-agent baselines across all evaluated metrics. As illustrated in Supplementary Figure˜S4.2, the objectives proposed by the agent are highly consistent across independent replicates and optimization iterations, with the majority (88.8%) corresponding to statistically driven objectives. Therefore, it also has more stable properties compared with other baseline agents, and indicates an advantage of using autonomous systems for scientific invention.

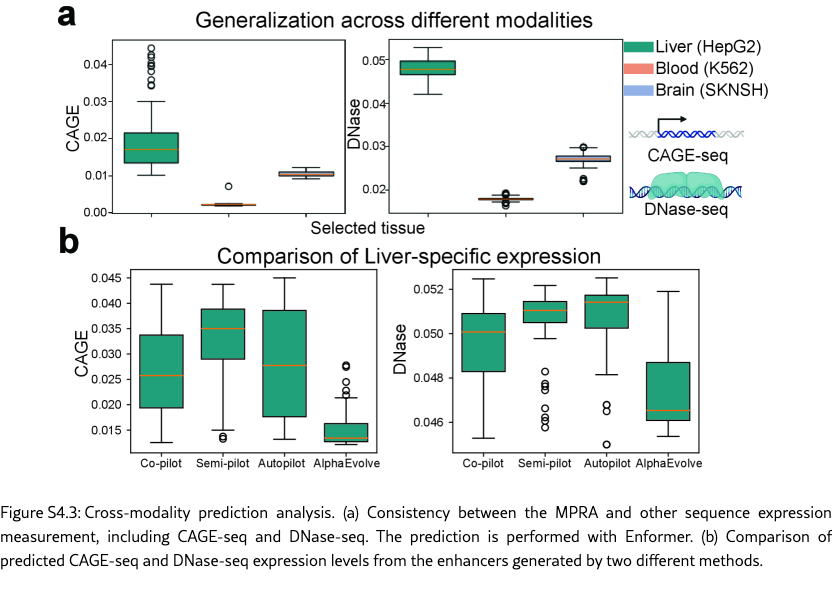

SAGA uncovers both novel enhancer candidates and known biological patterns. The discovery-oriented capability enables SAGA in different modes to design more novel enhancers beyond methods that rely on fixed, manually engineered scoring functions. As shown in Figure˜4(d), we compare the distributions from SAGA and AlphaEvolve with sampled HepG2-specific enhancers from a known experimental pool [? ]. The enhancers discovered by SAGA exhibit distinctly different distributions, and given their outstanding performance in held-out metric evaluations, we can leverage SAGA from different modes to design more enhancers with high quality. Moreover, SAGA also recapitulates key biological principles. Specifically, our method recovers multiple liver-specific transcription factor motifs [? ] (shown in Figure˜4(e)), supporting the biological plausibility of the designed sequences. When being evaluated on more biological-relevant multimodal regulatory readouts, including Cap Analysis Gene Expression sequencing (CAGE-seq) [? ] and DNase I hypersensitive sites sequencing (DNase-seq) [? ] predictions (shown in Figure˜S4.3 (a)), the designed enhancers again display strong HepG2 specificity, and they also show higher HepG2-specific expression levels compared with baseline methods (shown in Figure˜S4.3 (b)). These results highlight SAGA ’s ability to leverage information encoded in pre-trained sequence-to-function models such as Enformer [? ] to capture multimodal regulatory signals. In cell types where enhancers are active, lineage-defining and signal-responsive transcription factors bind to the enhancer sequence and recruit chromatin remodeling complexes, leading to localized chromatin opening and elevated DNase I hypersensitivity. This accessible chromatin state further facilitates the recruitment of the transcriptional machinery, giving rise to enhancer-associated bidirectional transcription that is captured by CAGE-seq [? ? ? ]. Together, the coordinated elevation of DNase-seq and CAGE-seq signals provides complementary evidence of functional enhancer activity, reinforcing that SAGA successfully designs enhancers that recapitulate authentic, cell-type-specific regulatory programs rather than optimizing for a single assay in isolation.

2.4 SAGA for Chemical Process Design

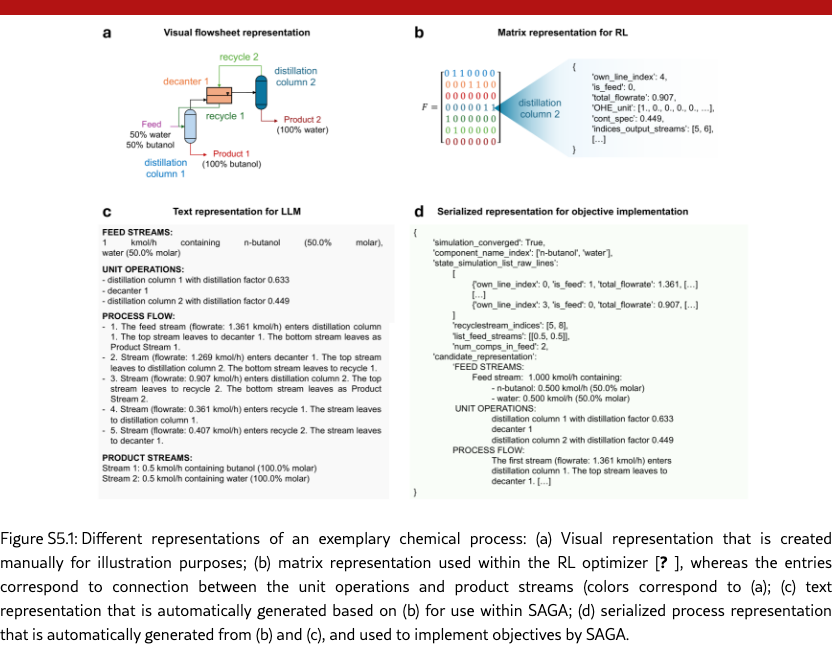

We consider the design of chemical processes for separation of mixtures, which is of high practical relevance within the chemical industry. The chemical process design task is quite novel and highly challenging to the LLM/agentic domain [? ? ]. In fact, only a few recent studies have utilized LLMs to optimize parameters for given processes, e.g., in [? ]; however, using LLMs to design chemical flowsheets from scratch is a largely unexplored area. While chemical process engineering has developed various heuristics and optimization-based approaches for the design of process flowsheets over the last decades, cf. [? ? ], they typically require manual input by domain experts. Recent works explore generative ML, in particular Reinforcement Learning (RL), promising to automate chemical process design, with exemplary applications in reaction synthesis, separation, and extraction processes [? ? ? ], and thereby highly accelerating chemical engineering tasks. However, current works focus on single design objectives predefined by human experts [? ], which can result in process flowsheets that lack characteristics of practical relevance and thus require iterative refinement in subsequent manual steps. SAGA advances automation of the process design loop by identifying process issues and proposing objectives that lead to more practical designs.

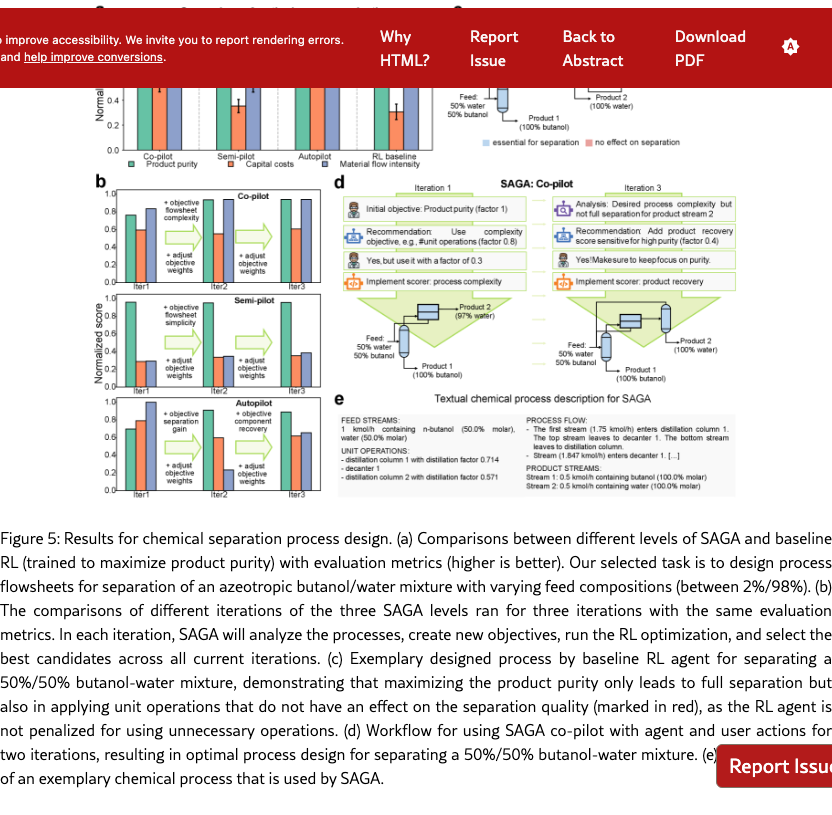

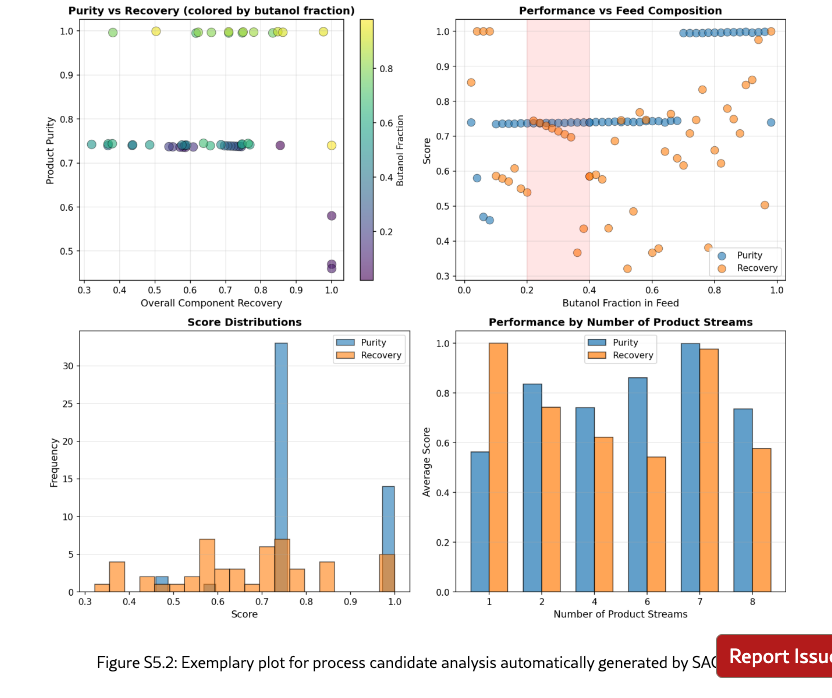

SAGA finds practically relevant processes by refining objectives in RL-based flowsheet design. Designing chemical process flowsheets, in particular with generative ML, is an iterative workflow, which involves refining objectives based on current designs. As shown in Figure˜5, using only the key objective of product purity for designing a separation process, i.e., the baseline, incentivizes the RL agent to propose a flowsheet that results in optimal purity. However, without considering further objectives, such as capital costs, the RL agent might place unit operations that do not have an effect on the separation quality, or use a more complex flowsheet structure than needed. When using SAGA, we observe increased objective scores for capital costs and material flow intensity compared to the RL baseline, whereas the purity is at a high level, close to ideal separation, see Figure˜5(a). SAGA effectively assists human experts (at the co- and semi-pilot levels) in the iterative refinement and addition of objectives which includes balancing multiple objective weighting factors, illustrated exemplary with the human-agent interaction in Figure˜5(d) and quantified along the iterations in Figure˜5(b). Also at the autopilot level, we observe significantly increased process performance. Therefore, SAGA enables automation of RL-based chemical process design, resulting in practically improved chemical processes.

SAGA identifies and implements objectives that align with early-stage chemical process design. Starting with maximizing the product purity as an initial objective, SAGA proposes a diverse set of useful objectives, such as process complexity, component recovery, and material efficiency, to be considered in the design. In fact, we find SAGA to identify and implement suitable process objectives and scoring functions at all levels (co-, semi- and autopilot), leading to higher overall scores on the evaluation metrics, cf. Figure˜5(a). Adding additional objectives to the optimization also requires setting appropriate objective weights, see, e.g., Figure˜5(d), since we combine multiple objectives into one reward for the RL design agent. As the design is sensitive to these objective weights, we see larger variation in individual objectives with less human intervention, particularly, for material flow intensity at semi- and autopilot level, see Figure˜5(a). Notably, the product purity across all levels also shows some slight variations, which can be explained by partly conflicting objectives, as SAGA achieves high gains in capital costs and material flow intensity compared to the baseline. Therefore, SAGA is able to enrich the chemical process design by relevant early-stage objectives.

SAGA effectively analyzes chemical processes based on text representations. To analyze the flowsheet designs and propose new objectives, SAGA requires a text representation of the chemical processes. As indicated in Figure˜5(e), we represent the flowsheets as natural text description with the four categories: feed streams, unit operations, process flow, and product streams. SAGA successfully utilizes this representation to analyze process design potentials, e.g., by highlighting suboptimal product purity, as shown in Figure˜5(d), and identifying unit operations and flowsheet patterns that result in desired separation, cf. Section˜S6.3. These examples highlight the capability of SAGA to capture complex process context and advance automated chemical process design.

3 Discussion

Scientific discovery is often limited not only by the vastness of the hypothesis space, but also by the “creativity” of defining objectives that ultimately leads to new discovery. Fixed proxy objectives can be incomplete, problem-specific, or vulnerable to misalignment and reward hacking, and are rarely sufficient to navigate open-ended discovery problems. SAGA, as a generalist agentic framework, address this challenge by iteratively evolving objectives and their realizations based on observed failure modes. By introducing an outer loop that proposes new objectives, implements executable scoring functions, analyzes outcomes, and selects final candidates, SAGA makes objective formulation a dynamic and autonomous discovery process.

Across four tasks spanning antibiotic design, inorganic materials design, functional DNA sequence design, and chemical process design, we find that iterating objectives is the key driver of progress in achieving final discovery. In antibiotic design, SAGA grounds the optimization of biological activity in chemical reality, ensuring that high predicted potency reflects genuine therapeutic potential rather than exploitation of the predictive model. In inorganic materials design, SAGA proposes objectives targeting mechanical properties and thermodynamic stability for superhard materials, which lead to excellent quality in the designed materials. In functional DNA sequence design, SAGA discovers biology-driven objectives for joint optimization with expression-associated objectives, and designs enhancers with both significant novelty and and strong cell-type-level specificity. In chemical process design, SAGA reveals excessively complex flowsheet structures in the designed processes and circumvents them by considering the process complexity and flow intensity which results in practically more relevant flowsheets.

A clear advantage of SAGA comes from its alignment with scientific practice: discovery is typically an interactive loop in which scientists interpret intermediate results, revise what to optimize next, and decide which constraints matter the most at a given stage. SAGA balances the time and resources spent by human scientist effort and automated agents. SAGA operationalizes this workflow through an agentic system with multiple levels of automation. SAGA enables scientists to intervene with the discovery process when needed while retaining the ability to run autonomously when objectives and evaluation pipelines are sufficiently mature. This interpretability and controllability offer significant efficiency and flexibility across tasks. In antibiotic design, SAGA allows chemists to identify problematic motifs such as uncommon rings or extended conjugated systems at intermediate interaction points. As a result, chemists could inject synthesis-oriented constraints early on, effectively steering the model away from artifacts and toward a more realizable chemical space. Similarly, in functional DNA sequence design, SAGA analyzes the properties of designed enhancers or promoters from the previous iteration and figures out the problems such as high off-target rates and lack of cell-type-specific motif, which may inspire biologists to modify the coming objectives and finally improve the quality of candidates to match the biological constrains.

SAGA instantiates a new path towards automated AI scientist, where most current AI scientists rely on scaling model capability and tool space. The autopilot mode effectively discovers important objectives aligning with the goal of the task and implements the scoring functions to guide the optimization process. By assessing the failure modes in the optimized candidates across iterations, SAGA effectively leverages the optimization algorithm in the discovery process. One key advantage of this structure is mimicking the two thought modes, “thinking, fast and slow” [? ]. The inner loop optimization is thinking fast, exploring all reachable solutions given specific objectives and preferences, and the outer loop is thinking slow, evolving objectives and preferences given the full optimization results.

One limitation of SAGA is the reliance on computationally verifiable objectives. For science problems where results cannot be validated computationally at all, SAGA needs to be extended in two ways: (1) feedback or scoring provided by human or (2) autonomous lab-in-the-loop. Finally, the current high-level goals considered by SAGA often predefine the design space, e.g. all possible small organic molecules. To expand SAGA to handle more flexible tasks, SAGA needs to be extended to adjust the design space with high-level goal only being finding a drug for curing a certain disease, and automatically formulate the design space, such as small molecule binders, antibiotics, nanobodies or RNA sequences.

4 Methods

4.1 SAGA Framework

4.1.1 Overview

SAGA transforms open-ended scientific discovery into structured, iterative optimization by dynamically decomposing the high-level discovery goal into computable objectives and scoring functions. The framework comprises two nested loops: an outer loop that explores and evolve objectives for the optimization; and an inner loop that systematically optimize candidates against the scoring functions of the specified objectives.

The workflow proceeds as follows (Figure˜1(c)): users provide a high-level goal in natural language, such as “design novel antibiotic small molecules that are highly effective against Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteria,” and can optionally provide more context information such as task background or specific requirements, as well as initial objectives and initial candidates as the starting points. The system then iterates through four core agentic modules: (1) Planner formulates measurable objectives aligned with the overarching goal and informed by previous analysis; (2) Implementer realizes executable scoring functions for proposed objectives; (3) Optimizer optimizes candidates by iteratively generating and assessing candidates that maximize the objective scores, as the inner loop; and (4) Analyzer assesses progress and determines whether to continue optimization or terminate upon goal satisfaction.

4.1.2 Core Modules

Planner. This agent decomposes the scientific goal into concrete optimization objectives at each iteration. Given the goal and current candidate analysis, it identifies gaps between the present state and desired outcome, proposing computable objectives with associated names, descriptions, optimization directions (e.g., maximize or minimize), and (optional) objective weights.

Implementer. This agent instantiates callable scoring functions for proposed objectives. When the implementations are not provided with the initial objectives, it develops custom implementations by conducting web-based research on relevant computational methods and software packages, then implements and validates the scoring function within a standardized Docker environment to ensure executability and correctness.

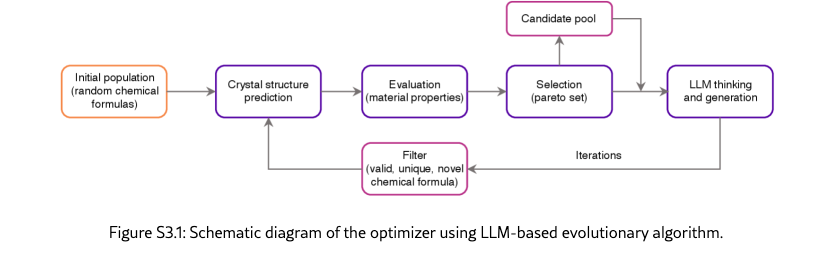

Optimizer. This module constitutes the inner optimization loop. Given objectives and their scoring functions, it employs established optimization algorithms to generate improved candidates. The process alternates between batch evaluation using objective scoring functions and generation of new candidates designed to outperform previous iterations. The architecture accommodates diverse optimization strategies, such as prompted language models, trained reinforcement learning agents, or any optimization algorithms, enabling flexible tuning. The default optimizer for SAGA is a simple LLM-based evolutionary algorithm with three essential steps: (1) candidate proposal: LLM proposes new candidates based on the current candidate pool, (2) candidate scoring: scores all proposed new candidates, and (3) candidate selection: constructs the updated pool from the previous pool and new candidates.

Analyzer. This agent evaluates optimization outcomes and recommends subsequent actions. It examines objective score trajectories, investigates candidate properties using computational tools, and synthesizes insights into actionable reports. The analyzer also determines whether candidates satisfy the goal and can trigger early termination when success criteria are met.

4.1.3 Autonomy Levels

SAGA aligns with human scientific discovery workflows and seamlessly supports human intervention at varying levels. We define three operational modes based on the degree of autonomy (Figure˜1(d)):

-

•

Co-pilot: Human scientists collaborate closely with both the planner and analyzer. At each iteration, these agents generate proposals (i.e., new objectives from the planner, and analysis from the Analyzer), which scientists can either accept directly or revise based on domain expertise. The implementer and optimizer operate autonomously within the outer loop, executing the human-approved objectives. This mode maximizes human control while automating implementation details.

-

•

Semi-pilot: Human intervention is limited to the analyzer stage. Scientists review progress reports and optimization outcomes, providing feedback that guides the planner’s subsequent objective proposal. The planner, implementer, and optimizer function autonomously, but strategic decisions about continuation, termination, or pivoting remain human-guided. This mode balances automation with critical oversight at decision points.

-

•

Autopilot: All four modules operate fully autonomously without human intervention. The system independently plans objectives, implements scoring functions, optimizes candidates, and analyzes results. This mode enables large-scale automated exploration when domain constraints are well-specified and trust in the system is established.

This tiered design ensures scientists can interact with SAGA in ways that maximize productivity for their specific research context, from hands-on collaboration to fully autonomous discovery.

4.2 Task Configurations

Antibiotic discovery. We formulate this task to discover novel small-molecule antibiotics against K. pneumoniae. In practice, we set the high-level discovery objective as designing candidates with strong predicted antibacterial efficacy while maintaining structural novelty, favorable predicted mammalian-cell safety, avoidance of dominant known-antibiotic motifs, and practical feasibility aligned with purchasable-like chemical space for wet-lab validation (details in section˜S2.2). Both the high-level goal and the accompanying contextual information explicitly encode our design target and related constraints (detailed in Section˜S2.2). For each SAGA instance, our initial objectives are always to maximize antibiotic activity, molecule novelty, and synthesizability, while minimizing toxicity to human and similarity to known antibiotic motifs in the designed molecules. During the loop of optimization, we use the default LLM-based evolutionary algorithm. The initial populations are selected from the Enamine REAL Database [? ], which also serves as the first group of molecules in the parent node. We provide molecules from the parent node, individual score from each objective, and an aggregated score (by product individual scores) to the LLM, and generate new molecules after crossover operation. We then select the top molecules based on the list containing both generated molecules and molecules from the parent node. To encourage diversity, we consider a cluster-based selection strategy (Butina cluster-based selection [? ] detailed in section˜S2.2). Finally, we combine all scoring functions into a single scalar value by product of expert to discourage ignoring any objective and select top molecules across all iterations. We use the standard implementation of the planner, implementer, optimizer, and analyzer modules.

Inorganic materials discovery. We consider two materials inverse design tasks. The first task aims to design permanent magnets with low supply chain risk, specified by two objectives: magnetic density higher than 0.2 and HHI score below 1500. The initial objective is set to maximize magnetic density. The SAGA Co-pilot mode is deployed with iteratively refined objectives: maximizing magnetic density in the first iteration, followed by the addition of HHI score minimization in the second. This task provides a direct comparison with MatterGen [? ]. The second task is to design superhard materials for precision cutting, requiring high hardness, high elastic modulus, appropriate brittleness, and thermodynamic stability. The high-level goal and contextual information explicitly encode design requirements and constraints (Supplementary Section Section˜S3.1.3 and Section˜S3.1.4). For each SAGA experiments of superhard materials design, initial objectives are set to maximize bulk modulus and shear modulus, which are important indicators for screening superhard materials [? ]. The optimization loop employs a default LLM-based evolutionary algorithm. Initial populations are randomly sampled from the Materials Project database [? ], which also serves as the first group of crystals in the parent node. Based on LLM-proposed chemical formulas, pretrained diffusion models provide 3D crystal structures, with geometric optimization performed using universal ML force fields [? ]. Evaluators assign objective scores based on the 3D structure of each crystal. Chemical formulas from the parent node and individual score of each objective were provided to the LLM, which generated new formulas through crossover operations. Optimal structures are then selected via Pareto front analysis from a combined pool of generated and parent crystals. The standard implementation of the planner, implementer, optimizer, and analyzer modules are used for all materials design tasks.

Functional DNA sequence design. Functional DNA sequences, also referred to as cis-regulatory elements (CREs), primarily include enhancers and promoters and play a central role in regulating gene expression levels [? ? ]. We focus on the de novo design of cell-type-specific enhancers and promoters across multiple cellular contexts, including HepG2 (enhancer and promoter), K562 (enhancer and promoter), SKNSH (enhancer and promoter), A549 (promoter only), and GM12878 (promoter only). The selection of these cell lines is constrained by the availability of high-quality, publicly accessible datasets. We formulate the discovery task using a high-level natural-language prompt that specifies the objective of generating functional DNA sequences with strong cell-type specificity. Both the high-level goal and the accompanying contextual information explicitly encode target and off-target cell-type constraints (see Sections˜S4.2.2 and S4.2.3). During optimization, the primary objectives are to maximize predicted expression in the target cell line while suppressing activity in non-target cell lines. For optimization, we employ a default LLM-based evolutionary algorithm. The initial population is selected by sampling from a pool of random DNA sequences. During candidate selection, we keep all candidates that satisfy the expression selectivity. Moreover, we also keep top 50% diverse candidates measured by average pairwise Hamming distance. Finally, we use the standard implementation of the outer loop and the analyzer, planner, and implementer agents.

Chemical process design. We use SAGA for the design of chemical process, more specifically separation process flowsheets, which is a central task in chemical engineering [? ? ? ]. The high-level goal is formulated as a natural language prompt targeting the design process flowsheets for the steady-state separation of an azeotropic binary mixture of water and ethanol at different feed compositions into high purity streams, cf. Section˜S5.2. For the optimizer designing process flowsheets in the inner loop, we use an RL agent based on the separation process design framework by ? ], see details in Section˜S5.2. The the action space of the RL agent comprises the (1) selection of suitable unit operations, such as decanters, distillation columns, and mixers with their specifications, and (2) determination of the material flow structures (including recycles) that connect the unit operations. We translate the RL-internal matrix representation of process flowsheets to a text description, see Figure˜S5.1 for details. We use the standard implementation of the analyzer, planner and implementer, and the text description is provided to the agents in the outer loop. The proposed new objectives – with corresponding weighting factors to aggregate the objective values into one reward value – are automatically added to the RL framework and used for the next iteration of process design, which always starts from scratch without an initial population, whereby the initial objective for the first iteration is the product purity. We thus focus on the iterative addition and refinement of suitable chemical process design objectives and their weighting factors.

4.3 Task Evaluations

We validate the performance of SAGA on each individual task by setting up a set of evaluation metrics. The evaluation metrics are unseen during the online running procedure of SAGA. Below, we briefly discuss the evaluation procedures for each task.

Antibiotic discovery. To mimic real-world lab experiment, we consider evaluating the candidates from the perspectives of biological objectives, synthesizability, and drug likeness. These three areas can be covered with 11 different computational metrics. To evaluate generated molecules with biological objectives, we consider antibiotic activity score, novelty score, toxicity score, and known motif filter score as metrics. For synthesizability, we consider a synthetic accessibility score as the metric. Last but not least, to evaluate drug likeness, we consider QED score, DeepDL prediction score, molecular weight score, PAINS filter score, BRENK filter score, and RING score as metrics. Detailed implementation and evaluation protocols are provided in Section˜S2.2. When evaluating candidates proposed by baselines and SAGA, we compute both the absolute score and pass rate of the top 100 molecules selected using each model’s optimization objectives for a fair comparison.

Inorganic materials design. To evaluate material properties, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to determine the electronic, magnetic, and mechanical properties of generated materials, as well as energy above hull [? ? ]. HHI scores were computed using the pymatgen package [? ]. In the task of designing permanent magnets with low supply chain risk, two objectives were specified: magnetic density higher than 0.2 and HHI score less than 1500. In the task of designing superhard materials for precision cutting, the evaluation metrics include Vickers hardness, bulk modulus, shear modulus, Pugh ratio, and energy above hull. More details of the evaluation protocols are described in Section˜S3.2.

Functional DNA sequence design. To emulate real-world experimental evaluation, we adopt a blind computational assessment framework based on five established computational oracles drawn from prior studies [? ? ? ? ]. As a representative task, we focus on the design of HepG2-specific enhancer sequences. The evaluation metrics include statistical comparisons of MPRA-measured expression between the target cell line and non-target cell lines (e.g., HepG2 vs. K562 and HepG2 vs. SKNSH), together with knowledge-driven criteria such as transcription factor motif enrichment, sequence diversity, and sequence stability. Detailed implementation and evaluation protocols are provided in Section˜S4.2.

Chemical process design. To cover early-stage process design goals, we utilize the short-cut simulations models developed in [? ] and calculate three process performance indicators. These are used as the evaluation metrics and include the product purity, capital costs, and material flow intensity. The product purity corresponds to the average purity of the product streams received from the simulation. The capital costs represent the sum of individual unit operation costs estimated on a simple heuristic, similar to [? ]. For the material flow intensity, we calculate the recycle ratios and introduce penalty terms for excessive ratios and very small streams ( of the feed stream). We refer to the Section˜S5.2 for further implementation details.

Acknowledgments

YD acknowledges the support of Cornell University. TL acknowledges the support of Yale Center for Research Computing especially Ms. Ping Luo. CPG acknowledges the support of an AI2050 Senior Fellowship, a Schmidt Sciences program, the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institute of Food and Agriculture (USDA/NIFA), the Air Force Office of Scientific Research (AFOSR), and Cornell University. ZS, HJ, and CD thank their entire team from Deep Principle for support. CD thanks Yi Qu for discussions. JC and PS acknowledge support from the NCCR Catalysis (grant number 225147), a National Centre of Competence in Research funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation. JGR acknowledges funding by the Swiss Confederation under State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation SERI, participating in the European Union Horizon Europe project ILIMITED (101192964). CM acknowledges Valence Labs for financial support. HS acknowledges the support of NSF CAREER #1942980. WJ acknowledges funding from Google Research Scholar Award and computational support from NVIDIA. KS, YW, and THG thank the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease grant U19-AI171954 for support.

Author Contributions

Coordination and planning: Yuanqi Du (lead), Botao Yu; Framework design and development: Botao Yu (lead); Task implementation: Tony Shen, Tianyu Liu, Junwu Chen, Jan G. Rittig, Yikun Zhang, Kunyang Sun, Cassandra Masschelein; Antibiotic discovery: Tony Shen (lead), Kunyang Sun (co-lead), Tianyu Liu (co-lead), Yikun Zhang, Yingze Wang, Bo Zhou and Cassandra Masschelein; Inorganic materials discovery: Junwu Chen (lead); DNA sequence design: Tianyu Liu (lead); Chemical process design: Jan G. Rittig (lead); Supervision and review: Haojun Jia, Chao Zhang, Hongyu Zhao and Martin Ester; Writing of the original draft: Yuanqi Du, Botao Yu, Wengong Jin, Tianyu Liu, Tony Shen, Jan G. Rittig, Kunyang Sun, Junwu Chen; Editing of the original draft: everyone; Supervision, conceptualization and methodology: Yuanqi Du, Teresa Head-Gordon, Carla P. Gomes, Huan Sun, Chenru Duan, Philippe Schwaller and Wengong Jin.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests at this time.

Bibliography

Supplementary Information for SAGA

Yuanqi Du1,*,†, Botao Yu2,*, Tianyu Liu3,*, Tony Shen4,*, Junwu Chen5,*, Jan G. Rittig5,*, Kunyang Sun6,*,

Yikun Zhang7,*, Zhangde Song8, Bo Zhou9, Cassandra Masschelein5, Yingze Wang6, Haorui Wang10,

Haojun Jia8, Chao Zhang10, Hongyu Zhao3, Martin Ester4, Teresa Head-Gordon6,†, Carla P. Gomes1,†,

Huan Sun2,†, Chenru Duan8,†, Philippe Schwaller5,†, Wengong Jin7,11,†

1Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA 2The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA 3Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA

4Simon Fraser University, Burnaby, BC, Canada 5École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland

6University of California Berkeley, Berkeley, CA, USA 7Northeastern University, Boston, MA, USA

8Deep Principle, Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China 9University of Illinois Chicago, Chicago, IL, USA

10Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta, GA, USA 11Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Cambridge, MA, USA

*These authors contribute equally

†Corresponding authors

Appendix S1 Implementation Details

S1.1 Framework Design

The SAGA framework translates high-level scientific goals into iterative optimization procedures targeting dynamically evolving sets of specific objectives. The system accepts the following inputs:

-

•

Goal: A high-level design goal specified in natural language that defines the scientific task.

-

•

Context information (optional): Supplementary descriptions of task background or specific requirements regarding objectives, enabling the framework to better understand the task domain and propose objectives aligned with domain-specific scientific needs.

-

•

Initial objectives (optional): Predefined objectives accompanied by their corresponding scoring functions, which are incorporated into the first iteration as a foundation for optimization.

-

•

Initial candidates (optional): Randomly initialized candidate solutions defining the initial search space.

Upon completion, SAGA outputs design solutions that satisfy the specified goal.

S1.1.1 Key Concepts

The framework defines four key concepts that structure information flow throughout the system:

Candidate represents an individual solution in the optimization space. Each candidate encapsulates a domain-specific representation (e.g., SMILES strings for molecular structures, multi-domain dictionary object for materials) and objective scores from multiple objectives. Candidates are uniquely identified and tracked across iterations, enabling provenance tracking and historical analysis.

Population manages collections of candidates as a cohesive unit. Beyond storing candidate lists, each population provides methods for batch objective scoring and statistics over stored candidates. Populations serve as the primary data structure passed between modules during optimization.

Objective specifies what should be optimized using a natural language description. Each objective can be one of the three types: candidate-wise objectives that evaluate individuals independently, population-wise objectives that assess collective properties, and filter objectives that enforce binary constraints. Each objective includes an optimization direction (maximize or minimize, not applicable for filter objectives) and an optional weight for multi-objective aggregation.

Scoring Function implements the computational logic for evaluating candidates against objectives. Scoring functions accept candidate representations and return numerical scores (for candidate-wise or population-wise objectives) or boolean values (for filter objectives). Each scoring function is implemented as an Model Context Protocol module, enabling isolated execution in Docker containers with standardized input/output interfaces. This design provides dependency isolation, reproducibility across environments, and safe execution of potentially unsafe code.

S1.1.2 Modules

The framework comprises four core modules (Figure˜S1.1) that implement the main optimization workflow:

Planner systematically decomposes the high-level scientific goal into concrete, computationally tractable objectives at each iteration. The module receives as input the optimization goal, optional context information that introduces the task background or specifies specific requirements, and analysis report from the last iteration. Through LLM-powered reasoning, it identifies gaps between the current state and desired outcomes, formulating objectives that specify what should be measured (description), how it should be optimized (maximize or minimize), and its relative importance (weight). Each objective must be specific enough to guide implementation and broad enough to capture meaningful scientific properties. The module outputs a structured list of objectives with complete specifications that guide subsequent implementation and optimization phases.

Implementer codifies abstract objectives into executable scoring functions. Given a list of proposed objectives, the module first attempts to match each objective with existing scoring functions that may be provided with the initial objectives or proposed in previous iterations through semantic similarity analysis, comparing objective descriptions using LLM-based pairwise evaluation. When an exact match cannot be found, the implementer autonomously implements new scoring functions through a multi-step process: (1) conducting web-based research to identify relevant computational methods, software packages, and scientific models; (2) synthesizing this information into executable Python code following standardized interfaces; (3) testing the implementation with specified dependencies and sample candidates. All scoring functions, whether retrieved or newly created, are deployed in isolated Docker containers with specified dependencies, ensuring reproducibility and preventing conflicts. The module outputs objectives with attached, validated scoring functions ready for optimization.

Optimizer executes the inner optimization loop, systematically generating and evaluating candidate solutions to optimize objective scores. The architecture supports diverse optimization algorithms, from evolutionary strategies to reinforcement learning agents, through a unified interface. The default implementation uses an LLM-based evolutionary algorithm that operates in three phases per generation: (1) candidate proposal, where the LLM analyzes high-performing candidates from the current population and generates novel candidates designed to improve upon observed patterns; (2) batch evaluation, where all candidates (existing and newly generated) are scored against each objective using their attached scoring functions, with parallel execution for efficiency; and (3) candidate selection, where the next generation’s population is assembled by ranking candidates according to weighted objective scores and maintaining fixed population size. Convergence detection monitors score improvement across consecutive generations, triggering early termination when progress plateaus. The optimizer receives the current population and objectives with scoring functions as input, and outputs an improved population.

Analyzer performs comprehensive evaluation of optimization progress and synthesizes actionable insights to guide subsequent planning. The module receives the current optimized population, active objectives, and historical summaries from previous iterations. It conducts multi-faceted analysis: computing statistical distributions of objective scores (mean, standard deviation, extrema) and comparing trends across iterations; identifying top-performing candidates and examining their properties to understand success patterns; assessing population diversity and detecting potential issues such as premature convergence or objective conflicts; and optionally employing domain-specific computational tools for deeper candidate investigation. The analysis synthesizes these quantitative and qualitative findings into a structured natural language report containing four sections: (1) overview summarizing current state and key characteristics; (2) performance analysis highlighting improvements, regressions, and trends; (3) issues and concerns identifying problems like stagnation or conflicting objectives; and (4) strategic recommendations proposing actionable adjustments for the next iteration. Beyond reporting, the analyzer makes a termination decision by evaluating whether optimization goals have been satisfied, whether scores have converged, and whether continued iteration would yield meaningful improvements. The module outputs an analysis report that informs the planner’s next objective formulation and a termination decision (continue or stop).

In addition to the above core modules, upon the end of the iterations, a selector agent is used to systematically evaluates all candidates generated throughout the optimization process, selecting solutions that best satisfy the discovery goal. It writes code and optionally call scientific tools to comprehensively assess and rank all candidates and returns a specified number of top candidates.

S1.2 Execution Workflow

The SAGA framework executes through a structured outer loop coordinated by the orchestrator, with each iteration progressing through five sequential phases:

Phase 0: Initialization. Before the first iteration begins, the system instantiates all modules and processes user-provided inputs. If users provide an initial population, it is stored and marked as iteration 0. If initial objectives with scoring functions are provided, the planner will be suggested to use them, and the implementer would omit implementing them on its own.

Phase 1: Planning. At the start of each iteration, the planner receives the optimization goal, optional context information that introduces task background or specifies specific requirements, and the analysis report from the previous iteration (iterations 2 onward). The Planner formulates objectives for the current iteration, considering optimization progress, remaining gaps, and strategic priorities.

Phase 2: Implementation. The Implementer processes each objective in parallel, attempting to match it with existing scoring functions through LLM-based semantic comparison or creating new implementations when matches are not found. If some objectives cannot be matched or implemented, the system records the unmatched objectives and invokes the planner with information about which objectives failed and why. The planner then revises its objective proposals to better align with available computational capabilities. This planning-implementation retry loop continues for up to a configurable maximum number of attempts until all objectives have attached scoring functions. Successfully matched objectives proceed to optimization.

Phase 3: Optimization. The optimizer receives the current population (from the previous iteration) and objectives with scoring functions. If configured, a specified ratio of the population is randomly replaced with newly generated random candidates to maintain diversity. The optimizer then executes its algorithm-specific optimization process, which for the default LLM-based evolutionary optimizer involves multiple generations of candidate proposal, batch evaluation, and selection until convergence criteria are met or generation limits are reached.

Phase 4: Analysis. The analyzer receives the optimized population, current objectives, and historical summaries. It evaluates all candidates against objectives, computes score statistics and trends, and conducts detailed candidate investigations using coding and domain-specific tools. The analysis results are synthesized into a structured report. The analyzer also evaluates termination criteria, including goal satisfaction, score convergence, and resource constraints, and recommends whether to continue to the next iteration or terminate optimization. If termination is not recommended and the maximum iteration count has not been reached, the workflow returns to phase 1 for the next iteration.

Phase 5: Finalization. Upon termination (either by analyzer decision or maximum iterations reached), the system invokes the Selecto to perform retrospective candidate evaluation. It retrieves all candidates generated across all iterations, evaluates them comprehensively against the original discovery goal using computational tools and custom analysis code, and selects the top candidates holistically with all objectives considered rather than solely by final-iteration scores. This retrospective selection ensures that high-quality solutions from early iterations exploring different objective combinations are retained. The system then collects the results and process logs and saves them for reproducibility and provenance.

S1.3 Experimental Setups

We used the following LLM settings for each module:

-

•

Planner: gpt-5-2025-08-07

-

•

Implementer: gpt-5-2025-08-07 for matching existing scoring functions to objectives, and the Claude Code agent with claude-sonnet-4-5-2025-0929 for implementing new scoring functions.

-

•

Optimizer: Task-specific. Different tasks may use different LLMs as backbones.

-

•

Analyzer: the Claude Code agent with claude-sonnet-4-5-2025-0929 for investigating specific candidates, gpt-5-2025-08-07 for writing comprehensive analysis and making termination decisions.

-

•

Selector: the Claude Code agent with claude-sonnet-4-5-2025-0929.

For each of the tasks, the input includes a high-level goal that briefly describes the design goal, context information that provides task background or specifies specific requirements, a set of initial objectives with scoring functions and a population of randomly initialized candidates as the starting point. See task-specific sections for more details.

All code and configurations will be released online.

S1.4 Extensibility and Customization

The SAGA framework is designed for extensibility at multiple levels:

Custom Module Implementations. Each module defines an abstract base class with required methods. Users can implement custom modules by subclassing these bases and registering implementations in the module registry. For example, users can easily replace the default LLM-based optimizer with a genetic algorithm or Bayesian optimization, or implement new workflow and add advanced features for planner. This modular and extensible codebase enables SAGA to be continuously updated and customized to more tasks.

Custom Scoring Functions. Users can add manually implemented task-specific scoring functions by following a specific code template. This allows users to provide their existing objectives and corresponding computational methods to the system, for more accurate and faster optimization. The implementer agent will also refer to user-provided scoring functions when implementing new ones.

Configuration-Based Customization. The framework uses structured configuration files (JSON or YAML) that specify module selections and versions, LLM settings per module (model, temperature, max tokens), loop parameters (max iterations, convergence thresholds, random injection ratio), and logging verbosity and output directories. This configuration-driven design enables experimentation with different setups without code modification.

S1.5 SAGA Reduces to AlphaEvolve

The default optimizer agent is a simple evolutionary optimization algorithm, thus SAGA reduces to AlphaEvolve when the outer loop is disabled. AlphaEvolve only optimizes with fixed objectives as input. For AlphaEvolve experiments, we always use this default version without any specialized design.

Appendix S2 Antibiotic Discovery

S2.1 Supplementary Figures

S2.2 Experimental Setups

S2.2.1 Objectives, metrics and baselines

Here we describe the experimental setup for antibiotic discovery targeting on Klebsiella pneumonia.

Initial objectives. Our initial objectives are:

-

•

Maximize: Antibiotic activity, predicted by an ensemble of 10 Minimol [? ] models trained on an internal high-throughput screening dataset for bacterial inhibition. We utilize 5-fold cross validation to select the best model.

-

•

Maximize: Novelty, defined as , where is the Tanimoto similarity between the selected molecule and the closest known compound from a pre-defined pool with antibiotic indication.

-

•

Minimize: Toxicity, predicted by an ensemble of Chemprop [? ] models trained on mammalian cell toxicity data [? ].

-

•

Minimize: Known antibiotic motifs, comprising six major motif classes (sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, tetracyclic_skeletons, beta_lactams, pyrimidine_derivatives, quinolone), implemented via 19 SMARTS patterns covering common variations.

-

•

Maximize: Synthesizability, measured as the Tanimoto similarity to the closest compound from a subset of Enamine REAL database space [? ] to ensure the existence of a purchasable analog.

Evaluation metrics. We evaluate generated molecules using the following predictive scores and rule-based filters, together with fixed acceptance thresholds. Unless otherwise noted, all metrics are normalized to , with higher values indicating more desirable properties.

-

•

Antibiotic activity score is predicted by an ensemble of 10 Minimol [? ] models trained on an internal high-throughput screening dataset for bacterial inhibition. The final prediction is rescaled to be from 0 to 1. We classify a candidate as computationally active if it has a score of or higher.

-

•

Novelty score is defined as , where is the Tanimoto similarity to the closest known or investigated compound with antibiotic indication. We require novelty to be greater than or equal to .

-

•

Toxicity score is predicted by an ensemble of Chemprop [? ] models trained on mammalian cell toxicity data. Molecules are considered acceptable if toxicity to be greater than or equal to , indicating lower predicted cytotoxic risk.

-

•

Known antibiotic motifs filter comprises six major motif classes (sulfonamides, aminoglycosides, tetracyclic_skeletons, beta_lactams, pyrimidine_derivatives, quinolone), implemented via 19 SMARTS patterns covering common variations [? ]. A score of indicates no known motifs are present.

-

•

Quantitative estimate of drug likeness (QED) score is the quantitative estimation of drug likeness [? ], combining physicochemical properties into a single score in . We require QED to be greater than or equal to .

-

•

Synthetic accessibility (SA) score estimates how easily a molecule may be synthesized [? ], normalized to , where higher values indicate easier synthesis. We require SA to be greater than or equal to .

-

•

DeepDL drug likeness is an unsupervised deep-learning score trained on approved drugs and normalized from its original scale to . We require DeepDL to be greater than or equal to [? ].

-

•

Molecular weight score is a pass indicator that equals if molecular weight lies between and and otherwise; we require MW to be equal to .

-

•

PAINS filter is a binary score returning if no PAINS (A/B/C) alerts are present and otherwise; we require PAINS to be equal to .

-

•

BRENK filter assigns for no structural alerts, for exactly one alert, and for two or more alerts; we require BRENK to be greater than or equal to .

-

•

Ring score measures how common the molecule’s ring systems are relative to ChEMBL statistics [? ], where indicates common (or no) rings and indicates rare or unseen ring chemotypes. We require ring_score to be equal to .

Summarizing the above threshold, we define pass rate as the proportion of molecules whose selected properties are higher than a given threshold, over the whole population (Numerical setting determined by chemists: KP Activity, Novelty, Toxicity, Motifs, QED, SA, DeepDL, MW, PAINS, BRENK, RING. These sets of evaluation thresholds are also used to select final candidates for future experiments.

Baselines. We benchmark against four representative previous approaches spanning (1) general-purpose LLM-driven optimization, (2) generalist science language models, and (3) RL-based molecular generative model.

-

•

TextGrad [? ] is an LLM-based optimization framework that iteratively edits molecular SMILES strings using critique-style feedback from the scoring functions and LLMs.

-

•

NatureLM [? ] is a multi-domain, sequence-based science foundation model enabling instruction-driven generation/optimization across molecules, proteins, nucleic acids and materials.

-

•

REINVENT4 [? ] is based on reinforcement-learning fine-tuning of a SMILES generator to maximize (possibly multi-objective) scoring functions, with diversity-aware goal-directed design. We utilize the latest version of this package.

-

•

MolT5 [? ] is a T5-based molecule–language translation model supporting text-to-molecule and molecule-to-text generation.