Recursive Language Models

Abstract

We study allowing large language models (LLMs) to process arbitrarily long prompts through the lens of inference-time scaling. We propose Recursive Language Models (RLMs), a general inference strategy that treats long prompts as part of an external environment and allows the LLM to programmatically examine, decompose, and recursively call itself over snippets of the prompt. We find that RLMs successfully handle inputs up to two orders of magnitude beyond model context windows and, even for shorter prompts, dramatically outperform the quality of base LLMs and common long-context scaffolds across four diverse long-context tasks, while having comparable (or cheaper) cost per query.

1 Introduction

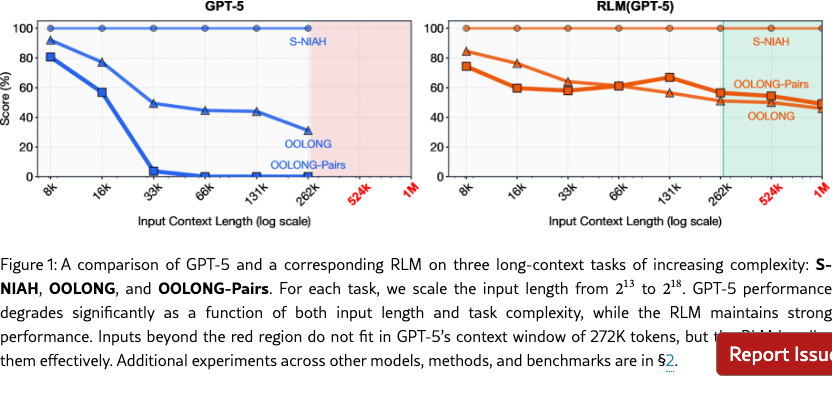

Despite rapid progress in reasoning and tool use, modern language models still have limited context lengths and, even within these limits, appear to inevitably exhibit context rot (hong2025contextrot), the phenomenon illustrated in the left-hand side of Figure 1 where the quality of even frontier models like GPT-5 degrades quickly as context gets longer. Though we expect context lengths to steadily rise through improvements to training, architecture, and infrastructure, we are interested in whether it possible to dramatically scale the context size of general-purpose LLMs by orders of magnitude. This is increasingly urgent as LLMs begin to be widely adopted for long-horizon tasks, in which they must routinely process tens if not hundreds of millions of tokens.

We study this question through the lens of scaling inference-time compute. We draw broad inspiration from out-of-core algorithms, in which data-processing systems with a small but fast main memory can process far larger datasets by cleverly managing how data is fetched into memory. Inference-time methods for dealing with what are in essence long-context problems are very common, though typically task-specific. One general and increasingly popular inference-time approach in this space is context condensation or compaction (khattab2021baleen; smith2025openhands_context_condensensation; openai_codex_cli; wu2025resumunlockinglonghorizonsearch), in which the context is repeatedly summarized once it exceeds a length threshold. Unfortunately, compaction is rarely expressive enough for tasks that require dense access to many parts of the prompt, as it presumes in effect that some details that appear early in the prompt can safely be forgotten to make room for new content.

We introduce Recursive Language Models (RLMs), a general-purpose inference paradigm for dramatically scaling the effective input and output lengths of modern LLMs. The key insight is that long prompts should not be fed into the neural network (e.g., Transformer) directly but should instead be treated as part of the environment that the LLM can symbolically interact with.

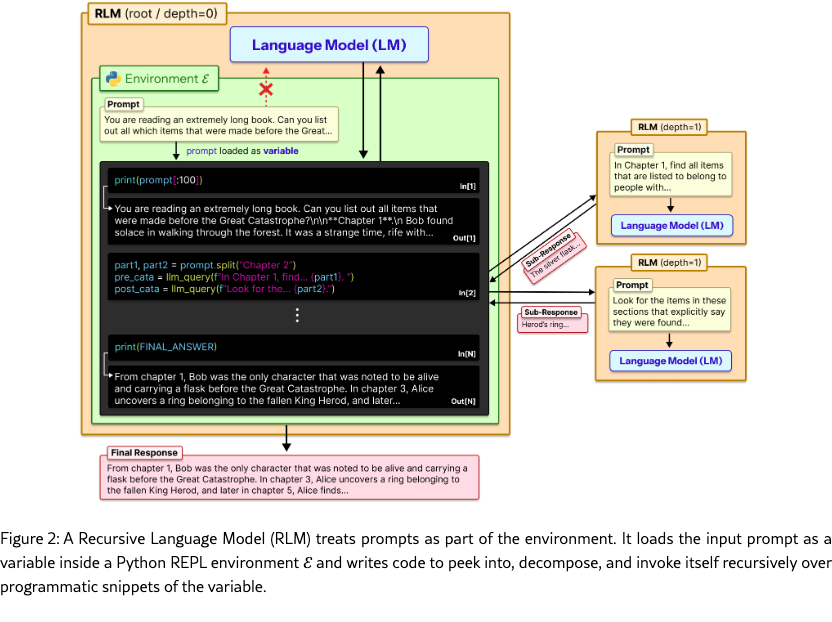

As Figure 2 illustrates, an RLM exposes the same external interface as an LLM: it accepts a string prompt of arbitrary structure and produces a string response. Given a prompt , the RLM initializes a Read-Eval-Print Loop (REPL) programming environment in which is set as the value of a variable. It then offers the LLM general context about the REPL environment (e.g., the length of the string ), and permits it to write code that peeks into and decomposes , and to iteratively observe any side effects from execution. Crucially, RLMs encourage the LLM, in the code it produces, to programmatically construct sub-tasks on which they can invoke themselves recursively.

By treating the prompt as an object in the external environment, this simple design of RLMs tackles a foundational limitation in the many prior approaches (anthropic_claude_code_subagents; sentient2025roma; schroeder2025threadthinkingdeeperrecursive; sun2025scalinglonghorizonllmagent), which focus on recursive decomposition of the tasks but cannot allow their input to scale beyond the context window of the underlying LLM.

We evaluate RLMs using a frontier closed model (GPT-5; openai2025gpt5systemcard) and a frontier open model (Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B; Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B) across four diverse tasks with varying levels of complexity for deep research (chen2025browsecompplusfairtransparentevaluation), information aggregation (bertsch2025oolongevaluatinglongcontext), code repository understanding (bai2025longbenchv2deeperunderstanding), and a synthetic pairwise reasoning task where even frontier models fail catastrophically. We compare RLMs against direct LLM calls as well as context compaction, retrieval tool-use agents, and code-generation agents. We find that RLMs demonstrate extremely strong performance even at the 10M+ token scale, and dramatically outperform all other approaches at long-context processing, in most cases by double-digit percentage gains while maintaining a comparable or lower cost. In particular, as demonstrated in Figure 1 exhibit far less severe degradation for longer contexts and more sophisticated tasks.

2 Scaling Long Context Tasks

Recent work (hsieh2024rulerwhatsrealcontext; goldman2025reallylongcontextneed; hong2025contextrot) has successfully argued that the effective context window of LLMs can often be much shorter than a model’s physical maximum number of tokens. Going further, we hypothesize that the effective context window of an LLM cannot be understood independently of the specific task. That is, more “complex” problems will exhibit degradation at even shorter lengths than simpler ones. Because of this, we must characterize tasks in terms of how their complexity scales with prompt length.

For example, needle-in-a-haystack (NIAH) problems generally keep ‘needles’ constant as prompt length is scaled. As a result, while previous generations of models struggled with NIAH tasks, frontier models can reliably solve these tasks in RULER (hsieh2024rulerwhatsrealcontext) even in the 1M+ token settings. Nonetheless, the same models struggle even at shorter lengths on OOLONG (bertsch2025oolongevaluatinglongcontext), which is a task where the answer depends explicitly on almost every line in the prompt.111This intuition helps explain the patterns seen in Figure 1 earlier: GPT-5 scales effectively on the S-NIAH task, where the needle size is constant despite longer prompts, but shows faster degradation at increasingly shorter context lengths on the linear complexity OOLONG and the quadratic complexity OOLONG-Pairs.

2.1 Tasks

Grounded in this intuition, we design our empirical evaluation around tasks where we are able to vary not just the lengths of the prompts, but also consider different scaling patterns for problem complexity. We loosely characterize each task by information density, i.e. how much information an agent is required to process to answer the task, and how this scales with different input sizes.

S-NIAH. Following the single needle-in-the-haystack task in RULER (hsieh2024rulerwhatsrealcontext), we consider a set of 50 single needle-in-the-haystack tasks that require finding a specific phrase or number in a large set of unrelated text. These tasks require finding a single answer regardless of input size, and as a result scale roughly constant in processing costs with respect to input length.

BrowseComp-Plus (1K documents) (chen2025browsecompplusfairtransparentevaluation). A multi-hop question-answering benchmark for DeepResearch (OpenAI_DeepResearch_2025) questions that requires reasoning over multiple different documents. The benchmark provides a verified offline corpus of 100K documents that is guaranteed to contain gold, evidence, and hard negative documents for each task. Following sun2025scalinglonghorizonllmagent, we use 150 randomly sampled tasks as our evaluation set; we provide randomly chosen documents to the model or agent, in which the gold and evidence documents are guaranteed to exist. We report the percentage of correct answers. The answer to each task requires piecing together information from several documents, making these tasks more complicated than S-NIAH despite also requiring a constant number of documents to answer.

OOLONG (bertsch2025oolongevaluatinglongcontext). A long reasoning benchmark that requires examining and transforming chunks of the input semantically, then aggregating these chunks to form a final answer. We report scoring based on the original paper, which scores numerical answers as and other answers as exact match. We focus specifically on the trec_coarse split, which is a set of tasks over a dataset of questions with semantic labels. Each task requires using nearly all entries of the dataset, and therefore scales linearly in processing costs relative to the input length.

OOLONG-Pairs. We manually modify the trec_coarse split of OOLONG to include new queries that specifically require aggregating pairs of chunks to construct the final answer. In Appendix E.1, we explicitly provide all queries in this benchmark. We report F1 scores over the answer. Each task requires using nearly all pairs of entries of the dataset, and therefore scales quadratically in processing costs relative to the input length.

LongBench-v2 CodeQA (bai2025longbenchv2deeperunderstanding). A multi-choice code repository understanding split from LongBench-v2 that is challenging for modern frontier models. We report the score as the percentage of correct answers. Each task requires reasoning over a fixed number of files in a codebase to find the right answer.

2.2 Methods and Baselines

We compare RLMs against other commonly used task-agnostic methods. For each of the following methods, we use two contemporary LMs, GPT-5 with medium reasoning (openai2025gpt5systemcard) and default sampling parameters and Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B (yang2025qwen3technicalreport) using the sampling parameters described in Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B, chosen to provide results for a commercial and open frontier model respectively. For Qwen3-Coder, we compute costs based on the Fireworks provider (Qwen3-Coder-Fireworks). In addition to evaluating the base model on all tasks, we also evaluate the following methods and baselines:

RLM with REPL. We implement an RLM that loads its context as a string in the memory of a Python REPL environment. The REPL environment also loads in a module that allows it to query a sub-LM inside the environment. The system prompt is fixed across all experiments (see Appendix D). For the GPT-5 experiments, we use GPT-5-mini for the recursive LMs and GPT-5 for the root LM, as we found this choice to strike a powerful tradeoff between the capabilities of RLMs and the cost of the recursive calls.

RLM with REPL, no sub-calls. We provide an ablation of our method. In it, the REPL environment loads in the context, but is not able to use sub-LM calls. In this setting, the LM can still interact with its context in a REPL environment before providing a final answer.

Summary agent. Following sun2025scalinglonghorizonllmagent; wu2025resumunlockinglonghorizonsearch; yu2025memagentreshapinglongcontextllm, we consider an iterative agent that invokes a summary of the context as it is filled. For example, given a corpus of documents, it will iteratively view the documents and summarize when full. In cases where the provided context exceeds the model window, the agent will chunks the input to fit within the model context window and invoke the same strategy over these chunks. For GPT-5, due to the extremely high cost of handling large token inputs, we use GPT-5-nano for compaction and GPT-5 to provide the final answer.

CodeAct (+ BM25). We compare directly to a CodeAct (wang2024executablecodeactionselicit) agent that can execute code inside of a ReAct (yao2023reactsynergizingreasoningacting) loop. Unlike an RLM, it does not offload its prompt to the code environment, and instead provides it directly to the LM. Furthermore, following jimenez2024swebenchlanguagemodelsresolve; chen2025browsecompplusfairtransparentevaluation, we equip this agent with a BM25 (10.1561/1500000019) retriever that indexes the input context for tasks where this is appropriate.

3 Results and Discussion

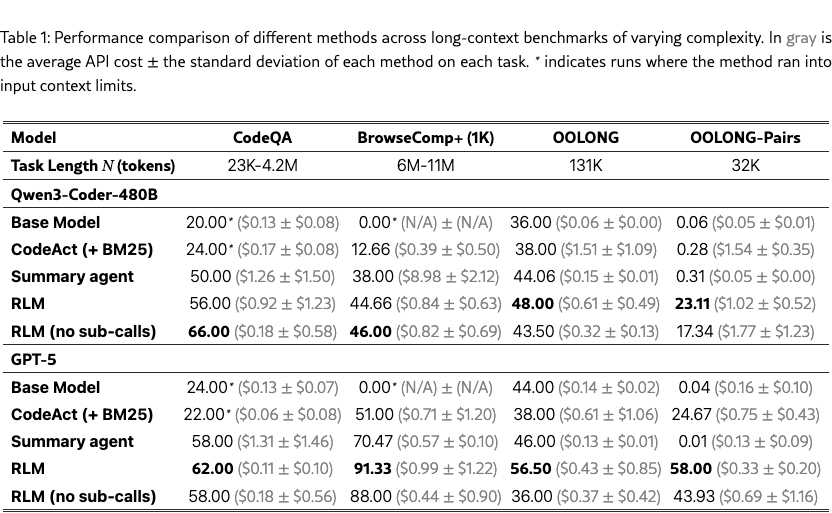

We focus our main experiments in Table 1 on the benchmarks described in §2.1. Furthermore, we explore how frontier model and RLM performance degrades as input contexts grow in Figure 1.

Observation 1: RLMs can scale to the 10M+ token regime and can outperform base LMs and existing task-agnostic agent scaffolds on long context tasks. Across all tasks, RLMs demonstrate strong performance on input tasks well beyond the effective context window of a frontier LM, outperforming base models and common long-context scaffolds by up to the performance while maintaining comparable or cheaper average token costs. Notably, RLMs scale well to the theoretical costs of extending a base model’s context window – on BrowseComp-Plus (1K), the cost of GPT-5-mini ingesting 6-11M input tokens is , while RLM(GPT-5) has an average cost of and outperforms both the summarization and retrieval baselines by over .

Furthermore, on tasks where processing costs scale with the input context, RLMs make significant improvements over the base model on tasks that fit well within the model’s context window. On OOLONG, the RLM with GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder outperform the base model by and respectively. On OOLONG-Pairs, both GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder make little progress with F1 scores of , while the RLM using these models achieve F1 scores of and respectively, highlighting the emergent capability of RLMs to handle extremely information-dense tasks.

Observation 2: The REPL environment is necessary for handling long inputs, while the recursive sub-calling of RLMs provides strong benefits on information-dense inputs. A key characteristic of RLMs is offloading the context as a variable in an environment that the model can interact with. Even without sub-calling capabilities, our ablation of the RLM is able to scale beyond the context limit of the model, and outperform the base model and other task-agnostic baselines on most long context settings. On the CodeQA and BrowseComp+ tasks with Qwen3-Coder, this ablation is able to outperform the RLM by and respectively.

On information-dense tasks like OOLONG or OOLONG-Pairs, we observed several cases where recursive LM sub-calling is necessary. In §3.1, we see RLM(Qwen3-Coder) perform the necessary semantic transformation line-by-line through recursive sub-calls, while the ablation without sub-calls is forced to use keyword heuristics to solve these tasks. Across all information-dense tasks, RLMs outperform the ablation without sub-calling by -.

Observation 3: LM performance degrades as a function of input length and problem complexity, while RLM performance scales better. The benchmarks S-NIAH, OOLONG, and OOLONG-Pairs contain a fixed number of tasks over a context with lengths ranging from to . Furthermore, each benchmark can be loosely categorized by different processing costs of the input context with respect to length (roughly constant, linear, and quadratic respectively). In Figure 1, we directly compare an RLM using GPT-5 to base GPT-5 on each task – we find that GPT-5 performance degrades significantly faster for more complex tasks, while RLM performance degrades but at a much slower rate, which aligns with the findings of goldman2025reallylongcontextneed. For context lengths beyond , the RLM consistently outperforms GPT-5.

Furthermore, RLM costs scale proportionally to the the complexity of the task, while still remaining in the same order of magnitude of cost as GPT-5 (see Figure 9 in Appendix C). In §3.1, we explore what choices the RLM makes in these settings that causes these differences in cost. Lastly, in this setting, we also observe that the base LM outperforms RLM in the small input context regime. By construction, an RLM has strictly more representation capacity than an LM: the choice of an environment that calls the root LM is equivalent to the base LM; in practice, however, we observe that RLM performance is slightly worse on smaller input lengths, suggesting a tradeoff point between when to use a base LM and when to use an RLM.

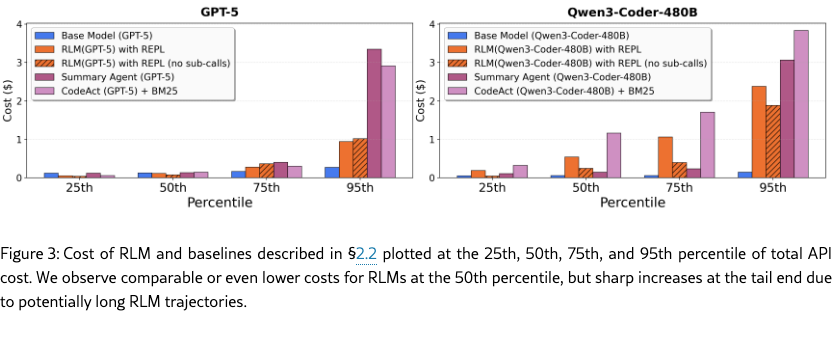

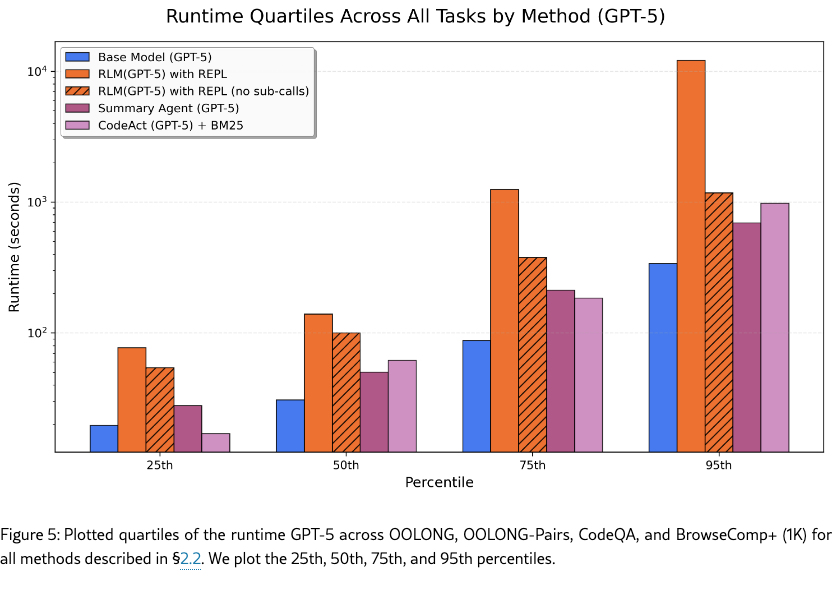

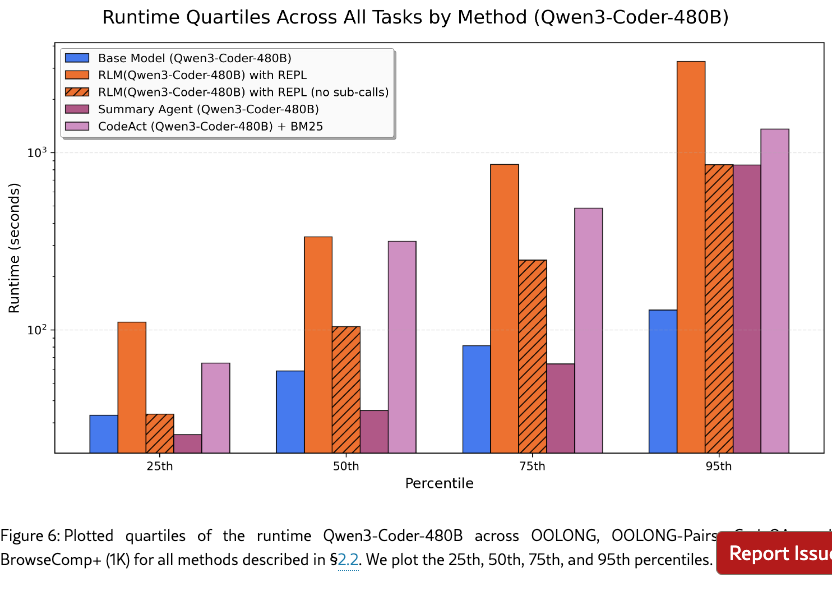

Observation 4: The inference cost of RLMs remain comparable to a base model call but are high variance due to differences in trajectory lengths. RLMs iteratively interact with their context until they find a suitable answer, leading to large differences in iteration length depending on task complexity. In Figure 3, we plot the quartile costs for each method across all experiments in Table 1 excluding BrowseComp-Plus (1K), as the base models cannot fit any of these tasks in context. For GPT-5, the median RLM run is cheaper than the median base model run, but many outlier RLM runs are significantly more expensive than any base model query. However, compared to the summarization baseline which ingests the entire input context, RLMs are up to cheaper while maintaining stronger performance across all tasks because the model is able to selectively view context.

We additionally report runtime numbers of each method in Figures 5, 6 in Appendix C, but we note several important caveats. Unlike API costs, these numbers are heavily dependent on implementation details such as the machine used, API request latency, and the asynchrony of LM calls. In our implementation of the baselines and RLMs, all LM calls are blocking / sequential. Nevertheless, similar to costs, we observe a wide range of runtimes, especially for RLMs.

Observation 5: RLMs are a model-agnostic inference strategy, but different models exhibit different overall decisions on context management and sub-calling. While GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder-480B both exhibit strong performance as RLMs relative to their base model and other baselines, they also exhibit different performance and behavior across all tasks. On BrowseComp-Plus in particular, RLM(GPT-5) nearly solves all tasks while RLM(Qwen3-Coder) struggles to solve half.

We note that the RLM system prompt is fixed for each model across all experiments and is not tuned for any particular benchmark. Between GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder, the only difference in the prompt is an extra line in the RLM(Qwen3-Coder) prompt warning against using too many sub-calls (see Appendix D). We provide an explicit example of this difference in example B.3, where RLM(Qwen3-Coder) performs the semantic transformation in OOLONG as a separate sub-LM call per line while GPT-5 is conservative about sub-querying LMs.

3.1 Emergent Patterns in RLM Trajectories

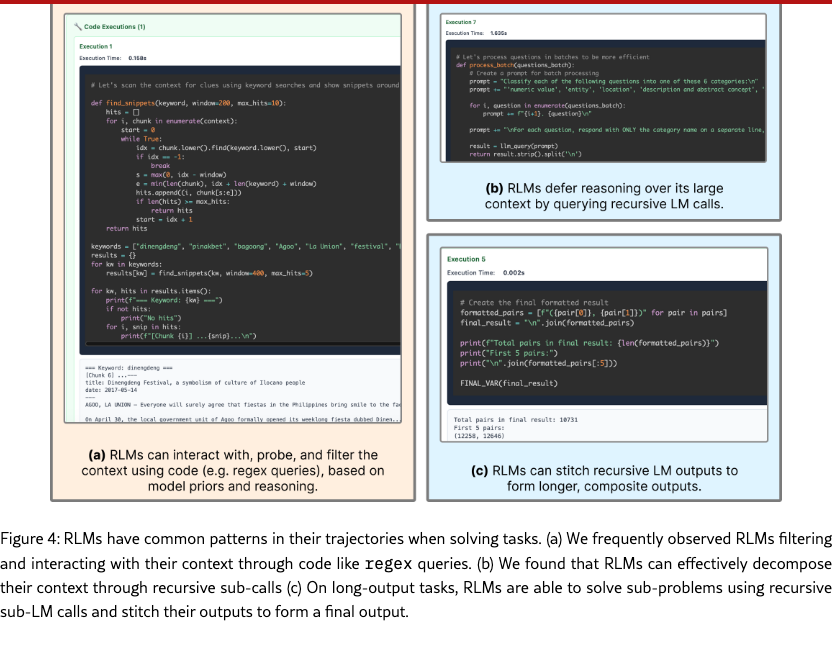

Even without explicit training, RLMs exhibit interesting context management and problem decomposition behavior. We select several examples of snippets from RLM trajectories to understand how they solve long context problems and where they can improve. We discuss particular examples of interesting behavior here, with additional examples in Appendix B.

Filtering input information using code execution based on model priors. A key intuition for why the RLM abstraction can maintain strong performance on huge inputs without exploding costs is the LM’s ability to filter input context without explicitly seeing it. Furthermore, model priors enable the RLM to narrow the search space and process fewer input tokens. As an example, in Figure 4a, we observed RLM(GPT-5) using regex queries search for chunks containing keywords in the original prompt (e.g. “festival”) and phrases it has a prior about (e.g. “La Union”). Across most trajectories, a common strategy we observed was probing the context by printing a few lines back to the root LM, then filtering based on its observations.

Chunking and recursively sub-calling LMs. RLMs defer essentially unbounded-length reasoning chains to sub-(R)LM calls. The choice of decomposition can greatly affect task performance, especially for information-dense problems. In our experiments, we did not observe complicated partitioning strategies beyond uniform chunking or keyword searches. In Figure 4b, RLM(Qwen3-Coder) chunks by newline in a 1000+ line context from OOLONG.

Answer verification through sub-LM calls with small contexts. We observed several instances of answer verification made by RLMs through sub-LM calls. Some of these strategies implicitly avoid context rot by using sub-LMs to perform verification (see example B.1), while others solely use code execution to programmatically verify answers are correct. In some instances, however, the answer verification is redundant and significantly increases the cost per task — in example B.3, we observed a trajectory on OOLONG where the model tries to reproduce its correct answer more than five times before choosing the incorrect answer in the end.

Passing recursive LM outputs through variables for long output tasks. RLMs are able to produce essentially unbounded tokens well beyond the limit of the base LM by returning variables in the REPL as output. Through the REPL, the RLM can iteratively construct these variables as a mixture of programmatic and sub-(R)LM output calls. We observed this strategy used heavily in OOLONG-Pairs trajectories, where the RLM stored the output of sub-LM calls over the input in variables and stitched them together to form a final answer (see Figure 4c).

4 Related Works

Long Context LM Systems. There have primarily been two orthogonal directions for long context management in language model systems: 1) directly changing the architecture of and retraining the base LM to handle longer contexts (press2022trainshorttestlong; gu2022efficientlymodelinglongsequences; munkhdalai2024leavecontextbehindefficient), and 2) building a scaffold around the LM that implicitly handles the context – RLMs focus on the latter. One popular class of such strategies is lossy context management, which uses summarization or truncation to compress the input context at the cost of potentially losing fine-grained information. For example, MemWalker (chen2023walkingmemorymazecontext) constructs a tree-like data structure of the input that the LM can navigate when answering long context questions. ReSum (wu2025resumunlockinglonghorizonsearch) is another work that adds a summarization tool to periodically compress the context of a multi-turn agent. Another class of strategies implement an explicit memory hierarchy in the agent scaffold (packer2024memgptllmsoperatingsystems; chhikara2025mem0buildingproductionreadyai; zhang2025gmemorytracinghierarchicalmemory). RLMs are different from prior work in that all context window management is implicitly handled by the LM itself.

Task Decomposition through sub-LM calls. Many LM-based agents (guo2024largelanguagemodelbased; anthropic_claude_code_subagents) use multiple, well-placed LM calls to solve a problem, however many of these calls are placed based on human-engineered workflows. Several methods like ViperGPT suris2023vipergpt, THREAD (schroeder2025threadthinkingdeeperrecursive), DisCIPL (grand2025self), ReDel zhu2024redel, Context Folding (sun2025scalinglonghorizonllmagent), and AgentFold (ye2025agentfoldlonghorizonwebagents) have explored deferring the choice of sub-LM calls to the LM. These techniques emphasize task decomposition through recursive LM calls, but are unable to handle long context inputs beyond the length of the base LM. RLMs, on the other hand, are enabled by an extremely simple intuition (i.e., placing the prompt as part of the external environment) to symbolically manipulate arbitrarily long strings and to iteratively refine their recursion via execution feedback from the persistent REPL environment.

5 Limitations and Future Work

While RLMs show strong performance on tasks beyond the context window limitations of existing LMs at reasonable inference costs, the optimal mechanism for implementing RLMs remains under-explored. We focused on synchronous sub-calls inside of a Python REPL environment, but we note that alternative strategies involving asynchronous sub-calls and sandboxed REPLs can potentially significantly reduce the runtime and inference cost of RLMs. Furthermore, we chose to use a max recursion depth of one (i.e. sub-calls are LMs); while we found strong performance on existing long-context benchmarks, we believe that future work should investigate deeper layers of recursion.

Lastly, we focused our experiments on evaluating RLMs using existing frontier models. Explicitly training models to be used as RLMs (e.g. as root or sub-LMs) could provide additional performance improvements – as we found in §3.1, current models are inefficient decision makers over their context. We hypothesize that RLM trajectories can be viewed as a form of reasoning (openai2024openaio1card; deepseekai2025deepseekr1incentivizingreasoningcapability), which can be trained by bootstrapping existing frontier models (zelikman2022starbootstrappingreasoningreasoning; zelikman2024quietstarlanguagemodelsteach).

6 Conclusion

We introduced Recursive Language Models (RLMs), a general inference framework for language models that offloads the input context and enables language models to recursively sub-query language models before providing an output. We explored an instantiation of this framework that offloads the context into a Python REPL environment as a variable in memory, enabling the LM to reason over its context in code and recursive LM calls, rather than purely in token space. Our results across multiple settings and models demonstrated that RLMs are an effective task-agnostic paradigm for both long-context problems and general reasoning. We are excited to see future work that explicitly trains models to reason as RLMs, which could result in another axis of scale for the next generation of language model systems.

Acknowledgments

This research is partially supported by the Laude Institute. We thank Noah Ziems, Jacob Li, James Moore, and the MIT OASYS and MIT DSG labs for insightful discussions throughout this project. We also thank Matej Sirovatka, Ofir Press, Sebastian Müller, Simon Guo, and Zed Li for helpful feedback.

Appendix A Negative Results: Things we Tried that Did Not Work.

Drawing inspiration from redmon2018yolov3incrementalimprovement, we try to be descriptive about what tricks, quirks, and other relevant things failed and succeeded in a concise manner. Some observations are based on longer supplementary experiments, while others are based on small samples of results.

Using the exact same RLM system prompt across all models can be problematic. We originally wrote the RLM system prompt with in context examples for GPT-5, and tried to use the same system prompt for Qwen3-Coder, but found that it led to different, undesirable behavior in the trajectory. We had to add a small sentence to the RLM system prompt for Qwen3-Coder to prevent it from using too many recursive sub-calls.

Models without sufficient coding capabilities struggle as RLMs. Our instantiation of RLMs relies on the ability to reason through and deal with the context in a REPL environment. We found from small scale experiments that smaller models like Qwen3-8B (yang2025qwen3technicalreport) struggled without sufficient coding abilities.

Thinking models without sufficient output tokens struggle as RLMs. In addition to Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B-Instruct, we also tried experimenting with Qwen3-235B-A22B as the RLM. While we found positive results across the board from the base model (e.g. on OOLONG (bertsch2025oolongevaluatinglongcontext), performance jumped from to ), the smaller gap compared to the evaluated models in the main experiments (Table 1) are due to multiple trajectories running out of output tokens while producing outputs due to thinking tokens exceeding the maximum output token length of an individual LM call.

RLMs without asynchronous LM calls are slow. We implemented all sub-LM queries naively as blocking / sequential calls, which caused our RLM experiments to be slow, especially compared to just the base model. We are confident that this can be resolved with a robust implementation.

Depending on the model, distinguishing between a final answer and a thought is brittle for RLMs. The current strategy for distinguishing between a “next turn” and a final answer for the RLM is to have it wrap its answer in FINAL() or FINAL_VAR() tags. Similar to intuition about structured outputs degrading performance, we also found the model to make strange decisions (e.g. it outputs its plan as a final answer). We added minor safeguards, but we also believe this issue should be avoided altogether in the future when models are trained as RLMs.

Appendix B Additional RLM Trajectories

In this section, we provide several example trajectories to highlight characteristics of frontier models as RLMs. Many of the trajectories are too long to fit in text (we also provide the raw trajectories and a visualizer in our codebase), so we describe each step and show specific examples when relevant.

A few noticeable properties of these trajectories are that RLMs often make non-optimal choices despite their strong results in §2. For example, in Example B.2, we observed that the RLM with Qwen3-Coder carefully constructs its final answer through a mix of recursive sub-calls and code execution in the first iteration, but then discards this information and continues wasting sub-calls before not using these stored answers. We also observed distinct differences in model behavior such as in Example B.3, where we found Qwen3-Coder make hundreds to thousands of recursive sub-calls for a single simple task, while GPT-5 makes on the order of ten. While these examples are not comprehensive, they provide useful qualitative insight into how to improve RLMs.

B.1 RLM(GPT-5) on BrowseComp-Plus-Query_74

The total cost of this trajectory was $0.079. In this task, the agent must find the answer to the following multi-hop query given a corpus of 1000 unique documents ( 8.3M total tokens) that contain evidence documents and negatives:

Step 1. GPT-5 (as the root LM) first decides to probe at the 1000 document list with regex queries. It has some priors about these events (as shown from its particular choice of words it looks for), but it also looks for specific keywords in the prompt like “beauty pagent” and “festival”.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/bcp-74_1.png)

Step 2. After running its regex queries, the root LM finds an interesting snippet on the chunk at index 6, so it launches a recursive LM call over this snippet to look for information relevant to the original query. The RLM is able to both store this information in a variable answer6, as well as print this information out for the root LM to see. The sub-LM call finds the answer is likely ‘Maria Dalmacio‘ and stores this information back in the root LM’s environment.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/bcp-74_2-1.png)

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/bcp-74_2-2.png)

Step 3. After checking the information above, the root LM reasons that it has enough information to answer the query. The root LM chooses to check its answer again with two additional recursive LM calls to confirm that its answer aligns with this check. Finally, the root LM returns its final answer as ‘Maria Dalmacio‘, which is the correct answer.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/bcp-74_3.png)

B.2 RLM(Qwen3-Coder) on OOLONG-Pairs-Query_3

The total cost of this trajectory was $1.12. In this task, the agent must output all pairs of user IDs satisfying some set of properties given a list of entries ( 32k tokens total). This is both an information dense long input as well as long output task, making it particularly challenging for current LMs.

Step 1. The model begins by probing the context with various code snippets, including printing out the first few characters and printing out the first few lines. We noticed in particular that Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B tends to output multiple code blocks in a single step unlike GPT-5, which makes outputs in a more iterative fashion.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op-3_1.png)

The model continues probing by splitting the input context by newline characters and checking roughly what the data format looks like.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op3_2.png)

From the given format, the model chooses to first semantically classify the data using sub-LM calls over smaller chunks of the input (to avoid context rot and mistakes in larger contexts) and provides a sample back to the root LM of what it observed during this process.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op3_3.png)

Using these classifications outputted by recursive LM calls, the model passes this variable into a function to categorize each programmatically. From here, the root LM is choosing to answer the rest of the question programmatically rather than by trying to output all pairs through model generaetions.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op3_4.png)

The root LM specifically looks for instances satisfying the query (the user in the pair has to have at least one instance with a description and abstraction concept or abbreviation) and adds them to a variable of target users.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op3_5.png)

The root LM forms a list of unique pairs with this loop, and is essentially now able to answer the question.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/op3_6.png)

The model has stored these pairs in a variable to be outputted at the end. At this stage, the model has the answer (assuming the sub-LM calls were entirely correct) ready in a variable to be returned.

Step 2. By this point the model has already successfully extracted the answer. Interestingly however, as we observed frequently with Qwen3-Coder, the model will continue to repeatedly verify its answers. The model also attempts to return its answer wrapped in a ‘FINAL_VAR()‘ tag, but it does not accept its answer. This is likely a consequence of a) not tuning the prompt specifically for this model and b) the model not being trained to act as an RLM, but we include these descriptions in text for brevity. At this step, the model checks its pairs.

Step 3. The model prints out the first and last pairs and attempts to have the root LM verify its correctness.

Step 4. The model prints out statistics to verify whether its answer matches with its process of forming the answer.

Step 5. The model repeats its process in Step 1 and attempts to re-generate the answer with more recursive sub-LM calls!

Step 6 - 11. The model repeats its process in Step 1 with slight difference and again attempts to re-generate the answer with more recursive sub-LM calls! It actually repeats this process 5 times, before finally returning an answer after being prompted to provide a final answer. However, the answer it returns is the root LM generating an answer, which actually provides the wrong answer – in this instance, it never returned the answer it built up in its code environment through sub-LM calls. This is an example of a case where the RLM failed.

B.3 RLM(Qwen3-Coder) on OOLONG-Query_212

The total cost of this trajectory was $0.38. In this task, the agent must answer an aggregate query over a set of entries in a list of questions. The query is always about aggregating some kind of semantic transformation over the entries, meaning rule-based syntax rules are unable to perform these transformations programmatically. In this example, the RLM is answering the following question:

Step 1. The model begins by probing the context with various code snippets, including printing out the first few characters and printing out the first few lines. Like in the OOLONG-Pairs example, we noticed that Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B tends to output multiple code blocks in a single step unlike GPT-5, which makes outputs in a more iterative fashion.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/o-212_1.png)

As mentioned previously, Qwen3-Coder differs from GPT-5 in how liberal it is in its use of sub-calls. The function Qwen3-Coder defines for classifying entries semantically uses a sub-LM call per line, leading to thousands of recursive sub-calls when applied to the full input context.

![[Uncaptioned image]](x2.png)

![[Uncaptioned image]](x3.png)

Step 2. After defining and testing several functions for running the above classification question over its input context, the root LM launches a long code execution call to classify and answer the query.

![[Uncaptioned image]](trajectories/o-212_3.png)

Final. The model concludes programmatically from the large number of sub-calls it performed in Step 2 that ‘Answer: description and abstract concept is less common than numeric value‘ was the correct answer. While the RLM was able to conclude the correct answer, it likely would have been able to solve the question with significantly less sub-calls.

B.4 RLM(GPT-5) on CodeQA-Query_44

The total cost of this trajectory was $0.27. In this task, the agent must answer a question that involves understanding a large codebase. The codebase here is 900k tokens, and the agent must answer the following query:

Step 1. It is not always true that an input context can be solved by partitioning it and recursively sub-querying models over each partition, but in tasks that are not information dense, this is possible. In this case, the model chooses to break down the codebase into parts and sub-query LMs to look for clues. The model then aggregates these clues and provides a final answer as a separate sub-query.

![[Uncaptioned image]](x4.png)

Final. The RLM answers choice ‘1’, which is the correct answer.

Appendix C Additional Runtime and Cost Analysis of RLMs

We supplement the cost and runtime analysis of RLMs with additional, fine-grained plots. In Figures 7, 8 we include a histogram for the cost of each method on every task for both GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder. We generally observe long-tailed, high-variance trajectories for RLMs in both models.

We additionally include log-scaled runtime plots for each method below. As we remarked in §3.1, the runtime for these methods can be significantly improved through asynchrony of LM calls and additional prompting to discourage long sub-LM calls or code.

For the scaling plot in Figure 1, we also provide the average API cost per task.

Appendix D Additional Methods and Baseline Details

D.1 Prompts for Experiments

We focus on methods that are entirely task agnostic, so we fix our prompt for each method across all tasks. For the RLM prompt, the only difference between GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder is an added line in the beginning that warns Qwen3-Coder not to use too many sub-LM calls – we found in practice that without this warning, the model will try to perform a subcall on everything, leading to thousands of LM subcalls for basic tasks! In this section, we provide the system prompt used for all methods in §2.1 (other than the base model, which does not include a system prompt).

(1a) The system prompt for RLM with REPL for GPT-5:

(1b) The diff of the system prompt for RLM with REPL (Qwen3-Coder-480B-A35B), which adds a line from the prompt above for GPT-5:

(2) The system prompt for RLM with REPL (no sub-calls):

(3a) The system prompt for CodeAct with BM25. We give CodeAct access to a BM25 retriever for BrowseComp+ following experiments in the original paper (chen2025browsecompplusfairtransparentevaluation).:

(3b) The system prompt for CodeAct. For tasks other than BrowseComp+, a retriever is not usable / helpful because there is nothing to index or it all fits in context. We modify the prompt to remove the retriever.:

D.2 Summary agent baseline

The summarization agent baseline follows the scaffold presented in sun2025scalinglonghorizonllmagent; wu2025resumunlockinglonghorizonsearch; yu2025memagentreshapinglongcontextllm, which also mimics how contexts are typically compressed in a multi-turn setting in agents like Claude Code (anthropic_claude_code_subagents). In an iterative fashion, the agent is given inputs until its context is full, at which point it is queried to summarize all relevant information and continue. If the agent is given a context in a single step that is larger than its model context window, it chunks up this context and performs the summarization process over these chunks.

For our GPT-5 baseline, we chose to use GPT-5-nano to perform summarization to avoid exploding costs. This explains the large discrepancy in cost in Table 1 between GPT-5 and Qwen3-Coder on BrowseComp+, where the summary agent using Qwen3-Coder is nearly more expensive on average. On this task in particular, we found on a smaller set of random samples that the performance between using GPT-5 and GPT-5-nano is comparable.

Appendix E Additional Benchmark Details

We provide additional details about the benchmarks used to evaluate RLMs in §2.

E.1 OOLONG-Pairs Benchmark

To create OOLONG-Pairs, we synthetically generate new tasks based on the ground-truth labels for the OOLONG bertsch2025oolongevaluatinglongcontext trec_coarse split for input contexts of length in [1024, 2048, 4096, 8192, 16384, 32768, 65536, 131072, 262144, 524288, 1048576]. Similar to OOLONG, each question requires correctly predicing the semantic mapping for each entry.

Ensuring on OOLONG-Pairs. We noticed that many tasks that aggregate over pairs of entries could actually be solved without looking at the pairs and only looking at each entry in a linear fashion (e.g. using the principle of inclusion-exclusion in set theory), so we explicitly created questions that ask for all pairs satisfying some properties.

Task 1

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a numeric value or location. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 2

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with an entity or human being. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 3

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a description and abstract concept or abbreviation. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 4

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a human being or location, and all instances that are a human being for both users must be after January 6, 2023. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 5

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with an entity or numeric value, and all instances that are an entity for both users must be before March 15, 2023. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 6

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a location or abbreviation. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 7

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a description and abstract concept or numeric value, and all instances that are a numeric value for both users must be after February 1, 2023. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 8

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a human being or description and abstract concept. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 9

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with an entity or location, and all instances that are a location for both users must be after April 10, 2023. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 10

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) where both users have at least one instance with a numeric value or abbreviation, and all instances that are an abbreviation for both users must be before May 20, 2023. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 11

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with entity and one with abbreviation, and the other user has exactly one instance with entity. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 12

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least two instances with numeric value, and the other user has at least one instance with location and at least one instance with human being. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 13

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has exactly one instance with description and abstract concept, and the other user has at least one instance with abbreviation and at least one instance with entity. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 14

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with human being and at least one instance with numeric value, and the other user has exactly two instances with location. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 15

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with entity, at least one instance with location, and at least one instance with abbreviation, and the other user has exactly one instance with numeric value. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 16

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with description and abstract concept and at least one instance with human being, and the other user has at least two instances with entity and exactly one instance with abbreviation. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 17

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has exactly one instance with numeric value, and the other user has at least one instance with location and at least one instance with description and abstract concept. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 18

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with abbreviation and exactly one instance with human being, and the other user has at least one instance with entity and at least one instance with numeric value. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 19

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least two instances with location and at least one instance with entity, and the other user has exactly one instance with description and abstract concept and exactly one instance with abbreviation. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

Task 20

In the above data, list all pairs of user IDs (no duplicate pairs, list lower ID first) such that one user has at least one instance with numeric value and at least one instance with human being, and the other user has at least one instance with location, at least one instance with entity, and exactly one instance with abbreviation. Each of the questions can be labelled as one of the labels (the data does not provide the labels, you need to figure out the label from the semantics of the question): description and abstract concept, entity, human being, numeric value, location, abbreviation. In your answer, list all pairs in the format (user_id_1, user_id_2), separated by newlines.

E.2 Scaling Huge Document Corpuses in BrowseComp+

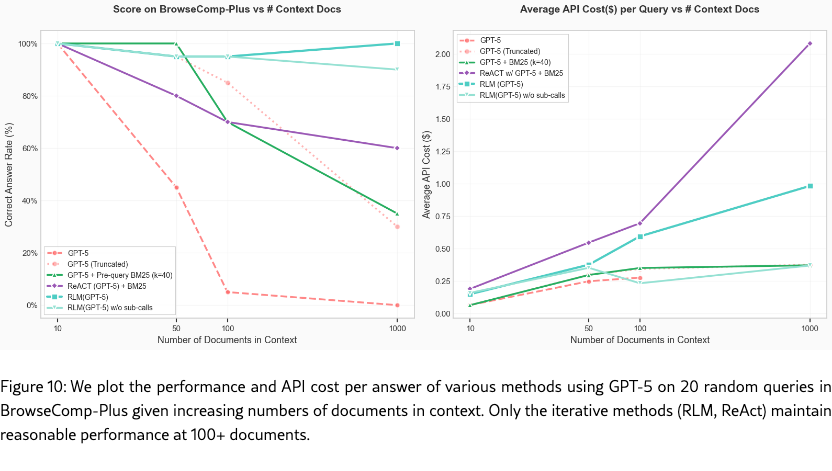

In addition to the BrowseComp+ (chen2025browsecompplusfairtransparentevaluation) results for documents in §3, we also include a smaller set of results on a subset of tasks from the original to show how performance degrades as a function of input size. In our original experiments, the base LMs were unable to handle the input contexts, so we add results to show how they degrade. We include two new baselines, namely ReAct w/ GPT-5 + BM25 (a variant of the CodeAct baseline without access to a code environment) and GPT-5 + pre-query BM25 (GPT-5 on pre-queried documents).

RLMs are able to scale well without performance degradation. RLM(GPT-5) is the only model / agent able to achieve and maintain perfect performance at the 1000 document scale, with the ablation (no recursion) able to similarly achieve performance. The base GPT-5 model approaches, regardless of how they are conditioned, show clear signs of performance dropoff as the number of documents increase.

RLM inference cost scales reasonably. The inference cost of RLMs on this setup scale log-linearly, and are reasonably bounded compared to other common strategies like ReAct + BM25. If we extrapolate the overall token costs of GPT-5 assuming it has an infinite context window, we observe that the inference cost of using RLM(GPT-5) is cheaper.