Enhancing Multimodal Retrieval via Complementary Information Extraction and Alignment

Abstract

Multimodal retrieval has emerged as a promising yet challenging research direction in recent years. Most existing studies in multimodal retrieval focus on capturing information in multimodal data that is similar to their paired texts, but often ignore the complementary information contained in multimodal data. In this study, we propose CIEA, a novel multimodal retrieval approach that employs Complementary Information Extraction and Alignment, which transforms both text and images in documents into a unified latent space and features a complementary information extractor designed to identify and preserve differences in the image representations. We optimize CIEA using two complementary contrastive losses to ensure semantic integrity and effectively capture the complementary information contained in images. Extensive experiments demonstrate the effectiveness of CIEA, which achieves significant improvements over both divide-and-conquer models and universal dense retrieval models. We provide an ablation study, further discussions, and case studies to highlight the advancements achieved by CIEA. To promote further research in the community, we have released the source code at https://github.com/zengdlong/CIEA.

Enhancing Multimodal Retrieval via Complementary Information Extraction and Alignment

Delong Zeng1,††thanks: Work done as an intern at Alibaba Group. Yuexiang Xie2 Yaliang Li2 Ying Shen1,3,††thanks: Corresponding author. 1School of Intelligent Systems Engineering, Sun Yat-sen University 2Alibaba Group 3Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Fire Science and Intelligent Emergency Technology zengdlong@mail2.sysu.edu.cn, {yuexiang.xyx, yaliang.li}@alibaba-inc.com sheny76@mail.sysu.edu.cn

1 Introduction

Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) Lewis et al. (2020b); Gao et al. (2023); Yi et al. (2024) has recently attracted widespread attention for its role in enhancing large language models (LLMs) Touvron et al. (2023); Bai et al. (2023); Chung et al. (2024); Brown et al. (2020) by providing up-to-date information and alleviating hallucination issues. Most existing studies focus on retrieving textual information Cheng et al. (2023); Shi et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2024a); Zhu et al. (2025), leveraging text corpora to provide factual support for model responses. As the scale of multimodal data continues to grow, effectively supporting multimodal retrieval to provide knowledge beyond text has emerged as a promising yet challenging research area Zhao et al. (2023); Kuang et al. (2025).

To promote the progress of multimodal retrieval, researchers have employed captioning models to convert multimodal data into text Wu et al. (2023); Baldrati et al. (2023); Mahmoud et al. (2024), enabling the application of existing retrieval techniques developed for text corpora. However, these approaches can be heavily influenced by the effectiveness of the captioning models, which might result in the loss of crucial information during the conversion process Che et al. (2023); Li et al. (2024b). Recent studies propose representation-based approaches, wherein textual and multimodal information are mapped into a unified embedding space for knowledge retrieval, after a separate encoding process Radford et al. (2021); Zhang et al. (2021) or a project-based joint encoding process Zhou et al. (2024); Li et al. (2024a).

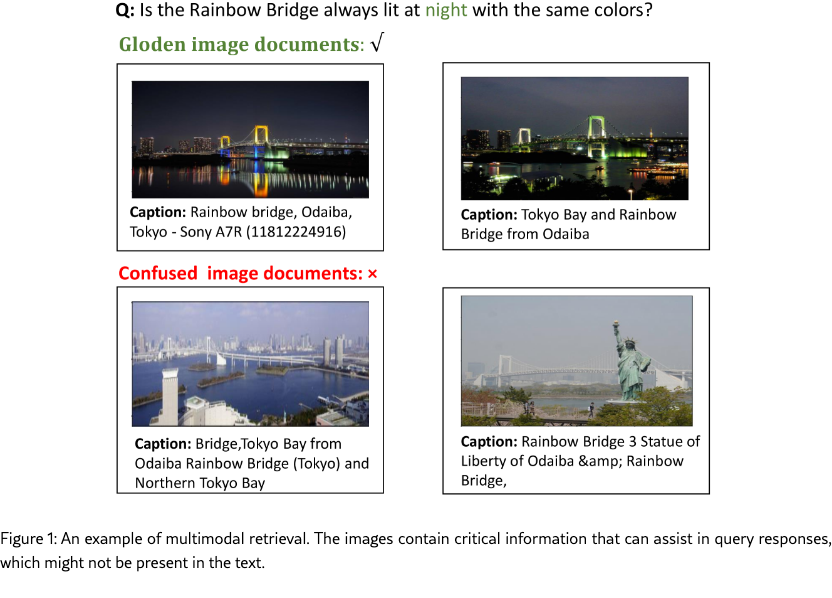

In this study, we focus on a novel representation-based approach that aims to transfer multimodal data into the latent vector space of language models. We identify a critical limitation of existing representation-based methods Wang et al. (2024b); Zhou et al. (2024): they tend to focus on capturing the information in multimodal data that is similar to their textual counterparts (such as captions or associated text) while neglecting the complementary information in multimodal data. For example, as shown in Figure 1, a textual description paired with an image might reference the Rainbow Bridge. While the image can indeed provide similar visual details of Rainbow Bridge, supplementary information such as the nightscape and the color of the bridge can also be important. For the representation-based approach, extracting and preserving such complementary information in multimodal data can enhance the quality of the responses to queries that cannot be fully resolved using textual information alone.

Inspired and motivated by the above insights, we propose a novel multimodal retrieval approach that involves Complementary Information Extraction and Alignment, denoted as CIEA. Specifically, we adopt a language model to transform text into a latent space, while employing the CLIP model Radford et al. (2021); Li et al. (2023) and a projector to map image information into the same unified latent space. Then, we design a complementary information extractor, which identifies the differences in representations between the images and the text in the documents. Based on these differences, we update the representations of the images to integrate complementary information. Furthermore, we introduce a novel optimization method tailored for CIEA by constructing two complementary contrastive loss functions: one that ensures the semantics integrity of the learned representations, and another that enhances the extraction of complementary information from the images.

Extensive experiments are conducted to demonstrate the effectiveness of CIEA in multimodal retrieval. The experimental results show that the proposed method achieves noticeable improvements compared to both divide-and-conquer models and universal dense retrieval models. An ablation study is carried out to highlight the contributions of the different components of CIEA. Besides, we provide further discussions on the effect of the language model and include some case studies for a better understanding of CIEA.

2 Related Work

Conventional retrieval models Lewis et al. (2020b); Yu et al. (2023) encode queries and documents into vectors via language models Chen et al. (2024), trained with contrastive learning and retrieved using KNN Su et al. (2022). Multimodal retrieval, compared to text-only retrieval, incorporates multiple modalities of information, necessitating effective utilization strategies for information from different modalities Yuan et al. (2021). One approach involves using caption models to convert information from other modalities into text, effectively converting multimodal retrieval tasks into text-only retrieval tasks Baldrati et al. (2023). However, such an approach may lead to information loss Che et al. (2023); Li et al. (2024b).

Another approach is to employ representation models, where visual and textual encoders encode information separately before fusion Radford et al. (2021). Early studies adopt a divide-and-conquer strategy, encoding each modality separately and concatenating vectors to fuse information, which potentially causes modality competition. To tackle this, UniVL-DR Liu et al. (2023b) proposes a universal multimodal retrieval framework by encoding queries and documents into a unified embedding space for retrieval, routing, and fusion. Some existing studies Wang et al. (2022a, b) involve training large models to unify text and visuals. However, differing representations complicate the acquisition of sufficient data for effective semantic understanding Lu et al. (2023).

Recent studies Zhou et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2024b); Li et al. (2024a, 2023) propose a project-based framework, which leverages models like CLIP Radford et al. (2021) to convert visual inputs into feature sequences and introduce projector layers to align these sequences with language model embeddings. Such a framework facilitates the comparison of visual and textual content at the embedding level and converts visual information into language model “tokens”, capitalizing on knowledge infused during the training of language models. For example, MARVEL Zhou et al. (2024) utilizes the project-based framework for capturing multimodal information within the output space of the language model; MCL Li et al. (2024a) adds a retrieval token for enhancing the model’s performance in representation learning.

Although remarkable progress has been made, visual information remains a novel and underexplored component for language models, which motivates us to provide effective solutions for processing visual information to attain a comprehensive representation for enhancing multimodal retrieval.

3 Methodology

3.1 Preliminary

In this study, we focus on multimodal retrieval, which aims to find one or more relevant documents from a knowledge base in response to a given text query . A knowledge base consisting of a total of documents can be denoted as . Each document might contain text and images, i.e., , where and represent the text and images in the document, respectively.

The main objective of multimodal retrieval is to align the representations of the query with the corresponding multimodal documents, ensuring that similar items are closely matched in a unified latent space. To achieve this, a multimodal encoder is employed to encode both the query and the documents, transforming them into dense representations, which can be given as:

| (1) |

After that, the similarities between the query and documents are measured via cosine similarity:

| (2) |

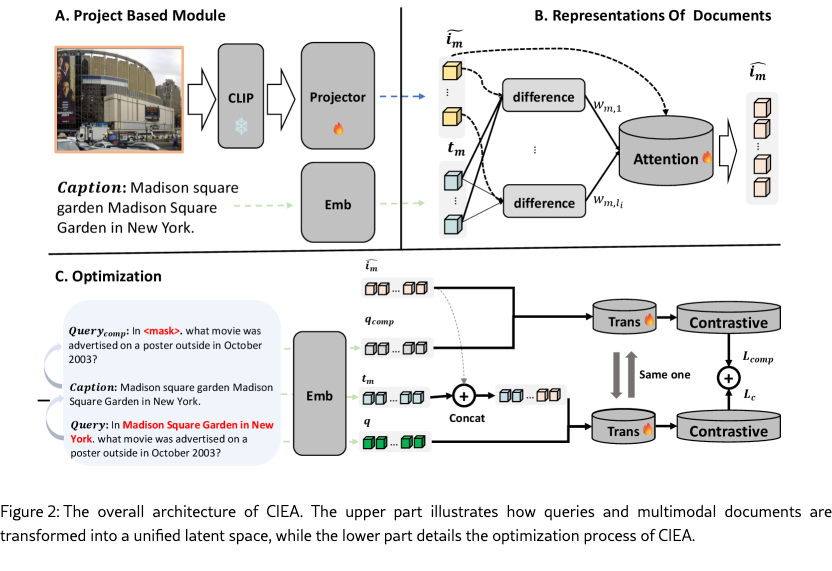

In the following subsections, we provide a detailed introduction of the proposed Complementary Information Extraction Alignment, denoted as CIEA. The overall architecture of CIEA is illustrated in Figure 2. Specifically, we first encode the queries and multimodal documents via a language model and a CLIP model, as shown in Section 3.2. Then, in Section 3.3, we design a complementary information extractor to capture the complementary information contained in the images. The optimization designed for the proposed CIEA is introduced in Section 3.4.

3.2 Representations of Queries and Multimodal Documents

Firstly, as shown in part A of Figure 2, we transform both the queries and the multimodal documents into their dense representations. Inspired by previous studies Zhou et al. (2024); Li et al. (2024a, 2023), we utilize a transformer-based language model as the backbone of the encoder to encode both text and images. A transformer-based language model typically consists of an embedding layer followed by several transformer blocks. We denote the embedding layer as and the transformer blocks as .

The text query can be transformed into dense representations via language models, which can be given as:

| (3) |

where , denotes the number of tokens in the query, and denotes the dimension of the dense representations.

For a document containing both text and images, i.e., , the text and image are processed separately before being fused. Specifically, we begin by feeding the text within the document to the embedding layer:

| (4) |

where and denotes the number of token in the text.

The images in the documents can typically be represented as RGB multi-channel matrices. We adopt a frozen CLIP Radford et al. (2021) visual encoder to transform these matrices into a set of semantic vectors. Such a process involves dividing an image into multiple patches, with each patch representing a different region of the image, which can be formally given as:

| (5) |

where , denotes the number of patches, and denotes the hidden dimension of CLIP visual encoder.

Note that the hidden dimension of these image representations might be different from that of text representations, i.e., . Therefore we adopt a linear layer as the projector for further alignment:

| (6) |

where .

3.3 Complementary Information Extractor

The proposed CIEA aims to capture the complementary information contained in images, i.e., the information not encompassed by the text in a document. To achieve this, we design a complementary information extractor that captures the differences between images and textual content. Specifically, we calculate the patch-level distances between text and image representations, identifying the maximum value to serve as a difference measurement, which is similar to those adopted in BLIP-2 Li et al. (2023). Formally, the difference between the -th patch of image and the text within document , denoted as , can be calculated as:

| (7) |

The obtained differences are normalized into a range of for effectively weighing the image patches, as given by:

| (8) |

We adopt an attention layer for re-weighting the patches of the image based on the calculated . The attention scores of embeddings are multiplied by the corresponding weights for normalization, which can be given as:

| (9) |

where are learnable matrices and “” here stands for the broadcasting method.

After that, as shown in part B of Figure 2, the embeddings of image and text are concatenated together and fed into transformer blocks for multimodal knowledge fusion. The obtained dense representation of the document can be given as:

| (10) |

where denotes the concatenate operation, and and denote the embeddings of special tokens <start> and <end>, respectively, for distinguishing the text and image embeddings explicitly.

Finally, for a given query, we rank the documents based on the similarities between their representations (refer to Eq.(10)) and the query representation (refer to Eq.(3)) to obtain the relevant documents.

3.4 Optimization

The trainable parameters of CIEA framework include the projector (as defined in Eq. (6)), the added attention weights for re-weighting (as defined in Eq. (9)), and the transformer layers of the language models (as defined in Eq. (10)). In this section, we introduce how to optimize these trainable parameters in CIEA.

Firstly, we identify the text segments from the queries in the training set that correspond to the text in the ground truth documents. For example, as shown in Figure 2, we mask out “Madison Square Garden in New York” that appears in the caption. We match the token IDs generated by the tokenizer of the language model for the query and the text in document for such identification.

After that, we replace these identified text segments with special tokens <mask> while preserving the remaining parts of the query. We denote the processed query as , whose representations can be obtained in a similar manner to the computation defined in Eq. (3):

| (11) |

We also construct negative samples for the queries to apply a contrastive loss for optimization. The documents annotated as relevant to the query are denoted as , while negative documents are sampled from the knowledge base and denoted as . The contrastive loss can be defined as:

| (12) |

where denotes the temperature, denotes the cosine similarity function, denotes the representation of the query, and denote the representations of positive documents and negative documents, respectively.

Meanwhile, to enhance the extraction of complementary information from images within the documents, we construct another contrastive loss function based on and the representations of images, which can be given as:

| (13) |

where denotes the representations of the images in the documents. The intuition behind the above loss function is that we promote the representations of images to align with the information contained in the query that is not present in the text within documents.

Finally, the training objective of the proposed CIEA can be given as:

| (14) |

where is a hyperparameter that balances the contributions of the two contrastive losses.

4 Experiments

4.1 Settings

Datasets

We conduct extensive experiments on the WebQA Chang et al. (2022) and EDIS Liu et al. (2023a) dataset to compare the proposed method against baselines. WebQA is an open-domain multimodal question answering dataset in which each query is associated with one or more relevant documents. There are 787,697 documents containing only textual information, while 389,750 documents contain both text and images. For clarity, we refer to this dataset as WebQA-Multi in this study. Besides, to better show the effectiveness of multimodal retrieval, we extract all documents containing images and construct the WebQA-Image dataset. EDIS retrieves images via textual queries, with 26,000 training, 3,200 development, and 3,200 test samples from 1M image corpus (each paired with a text caption). More statistics of datasets can be found in Appendix A.

Metrics

To evaluate the effectiveness of the proposed method and baselines in multimodal retrieval, we adopt six widely-used metrics, including MRR@10, MRR@20, NDCG@10, NDCG@20, REC@20, and REC@100. The MRR Bajaj et al. (2016) and NDCG Taylor et al. (2008) metrics are calculated using the official code111https://github.com/microsoft/MSMARCO-Passage-Ranking/blob/master/ms_marco_eval.py.

Implementation Details

In the experiments, we employ T5-ANCE Yu et al. (2023) as the foundational language model and CLIP as the visual understanding module to implement the proposed CIEA model to enhance the image understanding capabilities. The document representation capabilities of T5-ANCE are enhanced by using ANCE Xiong et al. (2021) to sample negative documents based on T5 Raffel et al. (2020). We truncate the text input length to 128 tokens. During training, we adopt the AdamW Loshchilov and Hutter (2019) optimizer with a maximum of 40 epochs, a batch size of 64, a learning rate of 5e-6, and set the temperature hyperparameter to 0.01. The hyperparameter is set to 0.0011 for WebQA-Multi, 0.019 for WebQA-Image, and 0.001 for EDIS, respectively. More implementation details can be found in Appendix B.

4.2 Baselines

We compare CIEA with two different types of baselines: divide-and-conquer models and universal dense retrieval models.

Divide-and-conquer models suggest retrieving image and text documents separately and then merging the retrieval results. We employ various single-modal retrievers to instantiate the divide-and-conquer models, including VinVL-DPR Zhang et al. (2021), CLIP-DPR Radford et al. (2021), and BM25 Robertson et al. (2009). The results of multi-modality retrieval are combined based on their uni-modal rank reciprocals or oracle modality routing. The latter approach demonstrates the maximum potential performance of our divide-and-conquer models in retrieval tasks.

Regarding universal dense retrieval models, we adopt the following recent studies as baselines: (i) Pre-trained multimodal alignment models VinVL-DPR Zhang et al. (2021) and CLIP-DPR Radford et al. (2021), which are trained using the DPR framework; (ii) UniVL-DR Liu et al. (2023b), which employs modality-balanced hard negatives to train text and image encoders, and uses image language adaptation techniques to bridge the modality gap between images and text; (iii) MARVEL Zhou et al. (2024), a project-based approach that encodes image documents with CLIP and projects them into the embedding layer of a language model for fusion.

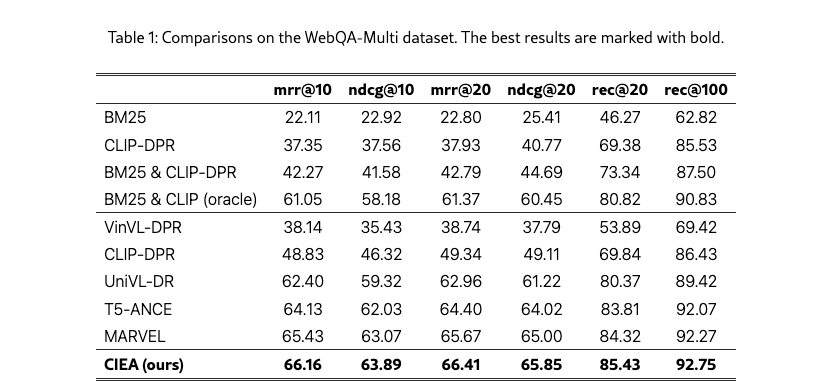

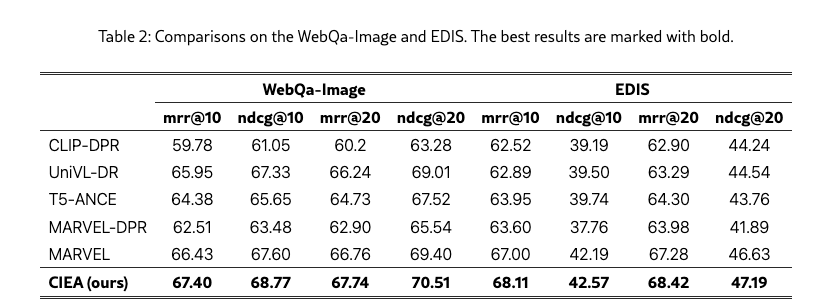

Comparisons

The experimental results on WebQA and EDIS are shown in Table 1 and 2, respectively. From these results, we can observe that the proposed CIEA achieves noticeable improvements across various metrics compared to both divide-and-conquer models and universal dense retrieval models. CIEA achieves outperformance on both WebQA and EDIS, demonstrating its effectiveness in capturing crucial information from both text and images for enhancing multimodal retrieval. As shown in Tables 1, compared to universal dense retrieval models that employ projectors for language model grounding (e.g., MARVEL, which shows improvement over text-only methods with a 1.3 MRR@10 improvement over T5-ANCE), CIEA achieves a further 0.74 MRR@10 improvement, with analogous enhancements replicated in Table 2. These CIEA-driven advancements underscore the critical benefits of complementary information alignment - a framework that enables superior visual information modeling and enhances the representational power of project-based models.

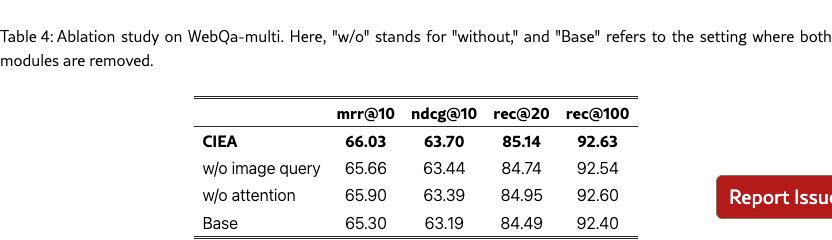

Ablation Study

We conduct an ablation study to demonstrate the contributions of the image query and the attention layer. Specifically, we remove the attention layer designed for re-weighting (refer to Eq. (9)) and the utilization of image query (refer to Eq. (13)), respectively. We also perform base setting by removing these two components.

The experimental results are shown in Table 4. Although the removal of the image query does not lead to a decrease in rec@100, other metrics exhibit varying degrees of decline, particularly rec@20, which drops from 85.14 to 84.74. On the other hand, the removal of the attention mechanism results in larger significant decreases in ndcg@10 metrics, highlighting the importance of complementary information extraction. Further, we also compare the baseline configuration with the simultaneous removal of both modules. The results indicate that removing a single module yields improvements in various metrics compared to the baseline, demonstrating that both the image query and the attention layer contribute to enhancing retrieval accuracy in multimodal retrieval. More results can be found in Appendix C.

4.3 Further Discussions

The Effects of Language Models in CIEA

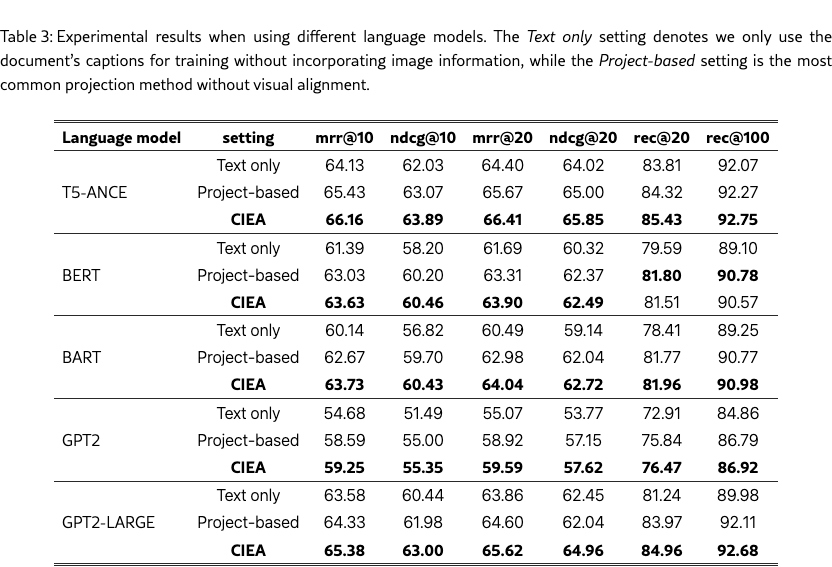

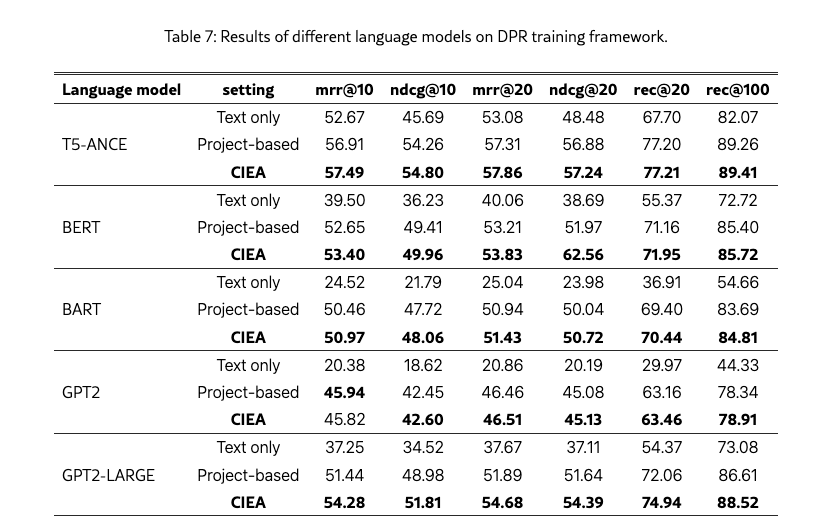

To provide further discussions regarding the effects of language models used in the proposed CIEA, we conduct experiments with different language models as the backbone, including T5-ANCE Yu et al. (2023), BART Lewis et al. (2020a), BERT Devlin et al. (2019), GPT-2, and GPT-2-LARGE Radford et al. (2019). These language models cover three mainstream architectures, i.e., encoder-decoder, encoder-only, and decoder-only. More implementation details can be found in Appendix D.

The experimental results in Table 3 demonstrate the significant impacts of the backbone language model on multimodal retrieval effectiveness. For text-only retrieval, language models with larger parameter sizes, such as GPT-2 LARGE and T5-ANCE, achieve better overall performance. Both project-based models and CIEA benefit from powerful backbones, showing performance gains through image-derived information. Notably, CIEA maintains competitive results across different backbones compared to project-based approaches, confirming its robustness.

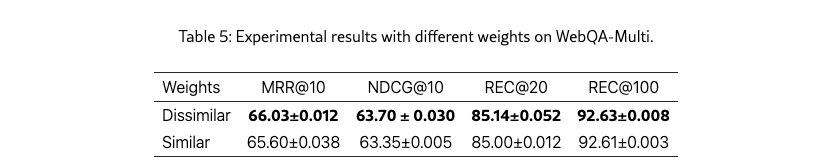

Attention Weight Selection

The application of maximum cosine similarity for computing patch-level similarities is designed to extract image regions exhibiting lower correspondence with textual descriptions. To determine the optimal extraction approach, we perform empirical experiments that retain original cosine values rather than their complements. As demonstrated in Table 5, explicit dissimilarity computation has proven more effective for capturing fine-grained patch-level image-text mappings.

Computational Efficiency

Although the proposed dual losses might increase training complexity, the computation of the losses is relatively independent and would not lead to a multiplicative increase in overall complexity. The proposed method achieves similar computational efficiency compared to MARVEL, which is also the project-based method. For example, with the sample devices, the training on the WebQA-Multid dataset with 4,966 samples with MARVEL needs around 6.1 minutes while that of CIEA is around 6.5 minutes.

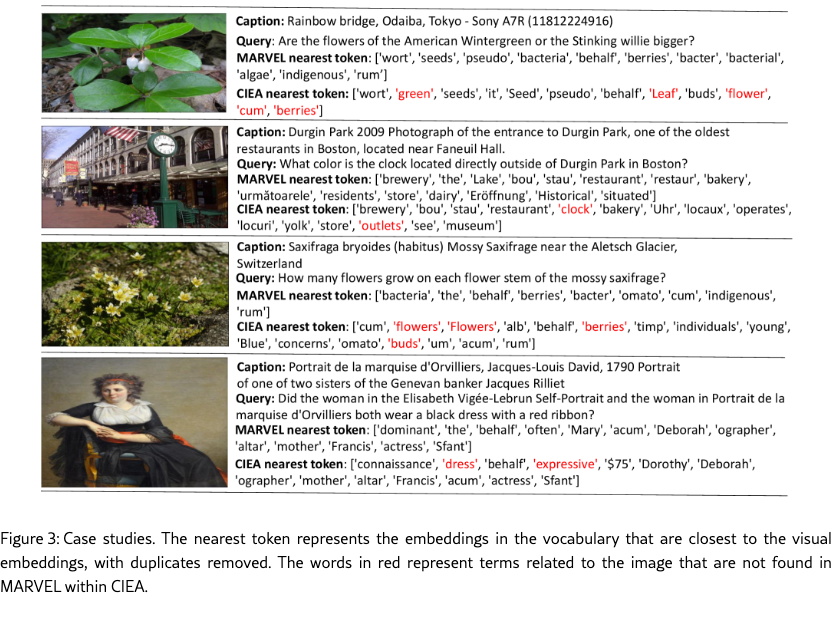

Case Study

We conduct case studies on the WebQA dataset for a better understanding. We apply cosine similarity to identify the words from the language model’s vocabulary that are closest to the embeddings projected from images, showing what information is extracted from images. We compare the proposed CIEA and the strongest baseline MARVEL. The results are illustrated in Figure 3, which indicates that MARVEL focuses on image information that is close to the text, while CIEA captures more supplemental information from images. For example, CIEA captures some terms, such as green, leaf, and clock, that are semantically related to the image but are not mentioned in the caption. The term clock in the second case and flowers in the third case are relevant to the query, which can assist the model in efficiently locating and retrieving relevant content. These results further confirm the advances of CIEA for multimodal retrieval. Discussions regarding the failure cases are provided in Appendix E, which further illustrate the model’s behavior in challenging scenarios and inspire future improvements.

5 Conclusion

In this paper, we propose CIEA to enhance the effectiveness of multimodal retrieval. The main idea of CIEA is to enhance the capturing of complementary information in multimodal data. Specifically, CIEA utilizes language models and CLIP to transform multimodal documents into a unified latent space. For complementary information extraction, we calculate the patch-level distances between text and images, which are then used to re-weight the image representations. Regarding the optimization of CIEA, besides applying a contrastive loss for learning the semantics of text, we also encourage the alignment of image representations with the complementary information in queries. We conduct a series of experiments to demonstrate the advantages of CIEA compared to two different types of multimodal retrieval approaches. Further discussions on the effect of language models show the robustness of CIEA, and several case studies are included for better understanding.

Limitations

Multimodal retrieval is currently in a phase of rapid development. In this paper, our exploration is limited to queries that contain only text, with a focus on extracting information from images. Expanding the proposed approach to include more types of multimodal data, such as audio and video, is a promising direction for future research. Besides, although we conduct experiments with various language models, we are constrained by computational resources and have not yet explored larger models.

Acknowledgement

This work is supported by Key-Area Research and Development Program of Guangdong Province (No.2024B1111100001).

References

- Qwen technical report. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.16609. Cited by: §1.

- Ms marco: a human generated machine reading comprehension dataset. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.09268. Cited by: §4.1.

- Zero-shot composed image retrieval with textual inversion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, pp. 15338–15347. Cited by: §1, §2.

- Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, pp. 1877–1901. Cited by: §1.

- Webqa: multihop and multimodal qa. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 16495–16504. Cited by: §4.1.

- Enhancing multimodal understanding with clip-based image-to-text transformation. In Proceedings of the 2023 6th International Conference on Big Data Technologies, pp. 414–418. Cited by: §1, §2.

- Benchmarking large language models in retrieval-augmented generation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Vol. 38, pp. 17754–17762. Cited by: §2.

- Lift yourself up: retrieval-augmented text generation with self-memory. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36, pp. 43780–43799. Cited by: §1.

- Scaling instruction-finetuned language models. Journal of Machine Learning Research 25 (70), pp. 1–53. Cited by: §1.

- BERT: pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 4171–4186. Cited by: Appendix D, §4.3.

- Retrieval-augmented generation for large language models: a survey. arXiv preprint arXiv:2312.10997. Cited by: §1.

- Natural language understanding and inference with mllm in visual question answering: a survey. ACM Computing Surveys 57 (8), pp. 1–36. Cited by: §1.

- BART: denoising sequence-to-sequence pre-training for natural language generation, translation, and comprehension. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 7871–7880. Cited by: Appendix D, §4.3.

- Retrieval-augmented generation for knowledge-intensive nlp tasks. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 33, pp. 9459–9474. Cited by: §1, §2.

- Blip-2: bootstrapping language-image pre-training with frozen image encoders and large language models. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 19730–19742. Cited by: §1, §2, §3.2, §3.3.

- Improving context understanding in multimodal large language models via multimodal composition learning. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 27732–27751. Cited by: §1, §2, §3.2.

- Monkey: image resolution and text label are important things for large multi-modal models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 26763–26773. Cited by: §1, §2.

- EDIS: entity-driven image search over multimodal web content. In Proceedings of the 2023 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 4877–4894. Cited by: Appendix A, §4.1.

- Universal vision-language dense retrieval: learning a unified representation space for multi-modal retrieval. In International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §2, §4.2.

- Decoupled weight decay regularization. In International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: Appendix B, §4.1.

- Chameleon: plug-and-play compositional reasoning with large language models. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 36, pp. 43447–43478. Cited by: §2.

- Sieve: multimodal dataset pruning using image captioning models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 22423–22432. Cited by: §1.

- Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pp. 8748–8763. Cited by: §1, §1, §2, §2, §3.2, §4.2, §4.2.

- Language models are unsupervised multitask learners. OpenAI blog 1 (8), pp. 9. Cited by: Appendix D, §4.3.

- Exploring the limits of transfer learning with a unified text-to-text transformer. Journal of Machine Learning Research 21 (140), pp. 1–67. Cited by: §4.1.

- The probabilistic relevance framework: bm25 and beyond. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval 3 (4), pp. 333–389. Cited by: §4.2.

- REPLUG: retrieval-augmented black-box language models. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 8364–8377. Cited by: §1.

- Contrastive learning-enhanced nearest neighbor mechanism for multi-label text classification. In Proceedings of the 60th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 672–679. Cited by: §2.

- Softrank: optimizing non-smooth rank metrics. In Proceedings of the 2008 International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, pp. 77–86. Cited by: §4.1.

- Llama: open and efficient foundation language models. arXiv preprint arXiv:2302.13971. Cited by: §1.

- GIT: a generative image-to-text transformer for vision and language. Transactions on Machine Learning Research. Cited by: §2.

- Searching for best practices in retrieval-augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 2024 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, pp. 17716–17736. Cited by: §1.

- SimVLM: simple visual language model pretraining with weak supervision. In International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §2.

- Unified embeddings for multimodal retrieval via frozen llms. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 1537–1547. Cited by: §1, §2.

- Cap4video: what can auxiliary captions do for text-video retrieval?. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 10704–10713. Cited by: §1.

- Approximate nearest neighbor negative contrastive learning for dense text retrieval. In International Conference on Learning Representations, Cited by: §4.1.

- A survey on recent advances in llm-based multi-turn dialogue systems. arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.18013. Cited by: §1.

- OpenMatch-v2: an all-in-one multi-modality plm-based information retrieval toolkit. In Proceedings of the 46th International ACM SIGIR Conference on Research and Development in Information Retrieval, pp. 3160–3164. Cited by: Appendix B, Appendix D, §2, §4.1, §4.3.

- Multimodal contrastive training for visual representation learning. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 6995–7004. Cited by: §2.

- Vinvl: revisiting visual representations in vision-language models. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, pp. 5579–5588. Cited by: §1, §4.2, §4.2.

- Retrieving multimodal information for augmented generation: a survey. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2023, pp. 4736–4756. Cited by: §1.

- MARVEL: unlocking the multi-modal capability of dense retrieval via visual module plugin. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 14608–14624. Cited by: Appendix A, Appendix B, Appendix D, §1, §1, §2, §3.2, §4.2.

- Knowledge graph-guided retrieval augmented generation. In Proceedings of the 2025 Conference of the Nations of the Americas Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, pp. 8912–8924. Cited by: §1.

Appendix A Datasets

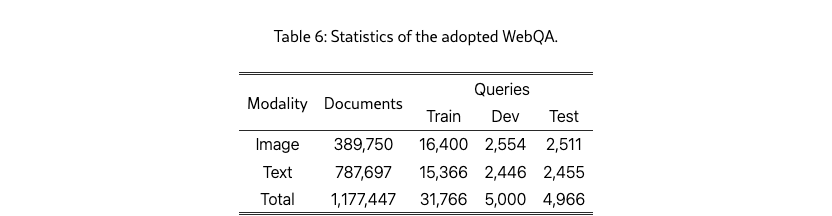

WebQA is an open-domain question answering dataset, where each query is associated with one or more multimodal documents to assist in generating responses. WebQA can be divided into three partitions: train, dev, and test, with data statistics as shown in Table 6. The retrieval corpus contains 389,750 image documents with visual information and captions, as well as 787,697 plain text documents. Our partitioned WebQA-Image focuses solely on image documents for testing the effectiveness of CIEA in multimodal modeling. In contrast, WebQA-Multi retrieves from a total of 1,177,447 documents to assess whether the model can maintain an accurate representation of text information.

WebQA is used by many baselines, such as MARVEL Zhou et al. (2024). ClueWeb22-MM is also utilized in MARVEL. We have applied for this dataset from Carnegie Mellon University; unfortunately, our request was denied due to export control restrictions. Therefore, we also use EDIS to evaluate our methods. EDIS Liu et al. (2023a) is a comprehensive dataset consisting of 1 million image-text pairs sourced from Google. The dataset includes a training set of 26,000 pairs, accompanied by validation and test sets, each containing 3,200 pairs. With a high entity count of 4.03, EDIS reflects a diverse range of semantic content, making it a valuable resource for research in image-text retrieval tasks.

Appendix B Implementation Details

In our experiment, we use T5-ANCE Yu et al. (2023) as the base language model and utilize CLIP as the visual understanding module to implement our CIEA model, enhancing the image understanding capability of T5-ANCE. For easier comparison, we initialize our projector using the pre-trained projector from MARVEL. The visual encoder is initialized using the clip-vit-base-patch32 checkpoint from OpenAI222https://huggingface.co/sentence-transformers/clip-ViT-B-32. We truncate the text input length to 128 tokens.

During the training process, we use the AdamW Loshchilov and Hutter (2019) optimizer, set the maximum training epochs to 40, with a batch size of 64, a learning rate of 5e-6, and the temperature hyperparameter set to 0.01. We follow the setup of UniVL-DR Loshchilov and Hutter (2019) by training with the ANCE sampling method. Starting from the CIEA-DPR model, fine-tuned with negative examples from within the batch, we continue to train CIEA-DPR to achieve a balanced modality with difficult negative examples. For negative sampling in evaluation, we shuffle the training set and select other samples within the same batch as negative examples in DPR, while in the ANCE approach, we utilize the top 100 samples with the highest similarity retrieval by CIEA-DPR as hard negatives. All models are evaluated every 500 steps, with early stopping set at 5 steps. For the parameter , we perform a grid search and select the parameter that yielded the lowest loss on the validation set, setting it to 0.0011 for WebQA-Multi, 0.019 for WebQA-Image, and 0.001 for EDIS. The results of various baselines for the WebQA-Multi dataset are provided in MARVEL Zhou et al. (2024), while the experimental results for other baselines are reproduced using the open-source code from the original papers. All experiments are conducted on a single NVIDIA A100.

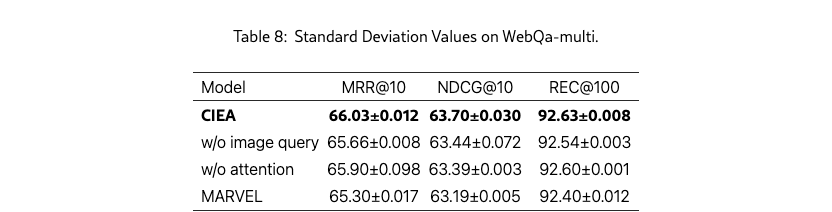

Appendix C Statistical significance

To avoid potential concerns that the results are justified, we repeat the experiments with different random seeds and report the average values and standard deviation values in Table 8. The results demonstrate the proposed CIEA achieves significant and consistent improvements compared to MARVEL. Besides, different modules make positive contributions to the overall performance of ICEA.

Appendix D The Effects of Language Models

The project-based approach relies on language models as the backbone, making the performance of the language model one of the key factors influencing retrieval effectiveness. To validate whether our method can function effectively with different language models as the backbone, we conduct experiments using T5-ANCE Yu et al. (2023), BART Lewis et al. (2020a), BERT Devlin et al. (2019), GPT-2, and GPT-2-LARGE Radford et al. (2019), encompassing encoder-decoder, encoder-only, and decoder-only architectures. For the encoder-decoder model, we follow MARVEL’s approachZhou et al. (2024) and encode the multimodal document input into the encoder, while inputting a ‘\s’ character into the decoder segment to use its final hidden layer representation as the document representation. For the encoder-only model, we use the representation of the first character, and for the decoder-only model, we use the final hidden layer representation of the last token, as each token only computes attention with preceding tokens. Due to the large number of parameters in GPT-2 LARGE, we set its batch size to 16 to avoid memory issues, while setting the batch size to 64 for the others. Besides the results trained with the ANCE negative sampling method presented in Table 3, we also include the results trained using the in-batch negative sampling method of DPR in Table 7. It is evident that while ANCE consistently outperforms DPR, CIEA surpasses both simple project-based and text-only methods under both negative sampling approaches, demonstrating that the proposed method aligns better with image information.

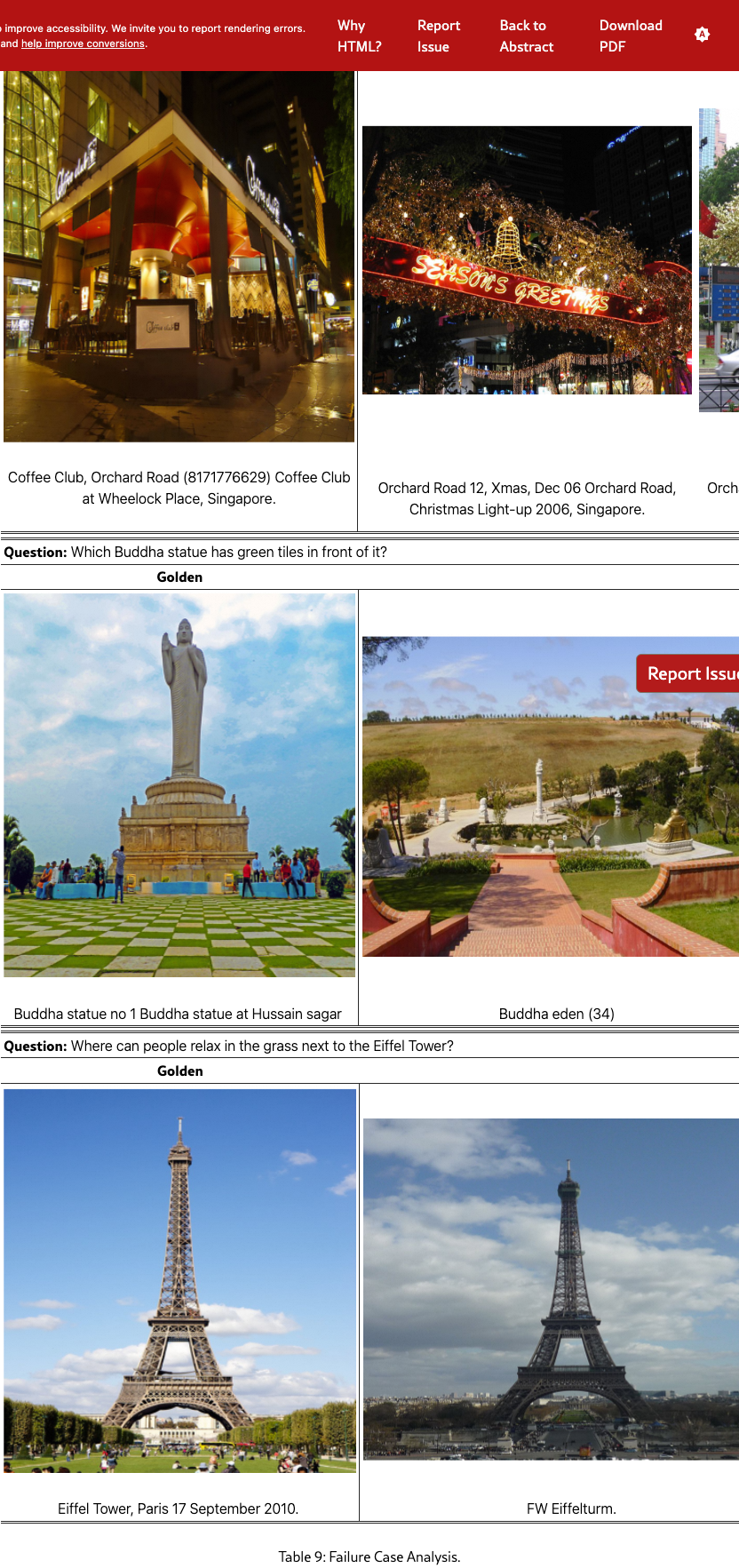

Appendix E Failure Case Analysis

We provide a failure case analysis in Table 9 for a better understanding of the proposed method and for promoting further research. Each case presents the ground-truth image-caption pair alongside the top three retrieved candidates from CIEA, with all instances classified as retrieval failures due to the absence of ground-truth matches among the top results. The first two cases illustrate the model’s partial success in capturing color attributes (e.g., “orange” and “green”), while it might struggle to establish precise color-object mappings (e.g., “ceiling” and “tiles”), especially within multi-object environments. The third case reveals more fundamental limitations regarding action interpretation, as the retrieved results exhibit minimal relevance to the target action “relax”. These failures highlight persistent challenges in visual-semantic alignment, particularly in the contextual binding of object attributes and the dynamic interpretation of action representations.