∗ Joint first author & Equal Contribution.

Corresponding to junsong@hkbu.edu.hk

CaveAgent: Transforming LLMs into Stateful Runtime Operators

Abstract

Abstract:

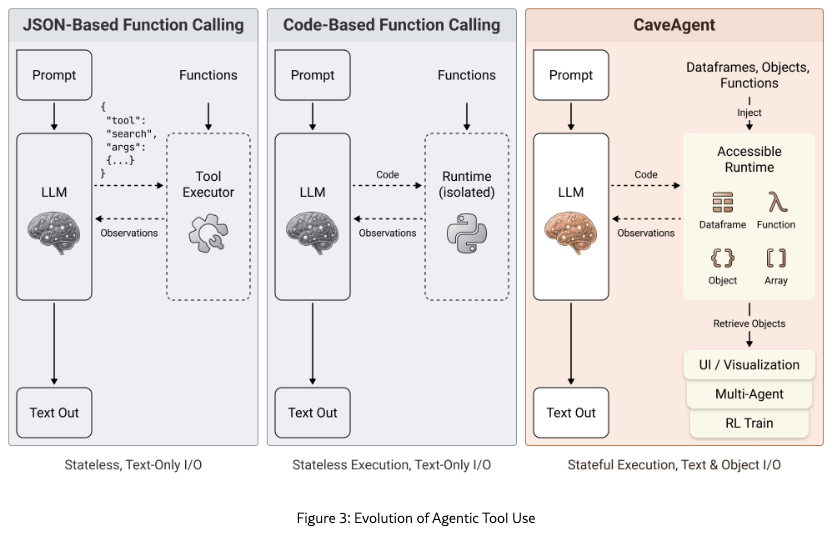

LLM-based agents are increasingly capable of complex task execution, yet current agentic systems remain constrained by text-centric paradigms. Traditional approaches rely on procedural JSON-based function calling, which often struggles with long-horizon tasks due to fragile multi-turn dependencies and context drift. In this paper, we present CaveAgent, a framework that transforms the paradigm from "LLM-as-Text-Generator" to "LLM-as-Runtime-Operator." We introduce a Dual-stream Context Architecture that decouples state management into a lightweight semantic stream for reasoning and a persistent, deterministic Python Runtime stream for execution. In addition to leveraging code generation to efficiently resolve interdependent sub-tasks (e.g., loops, conditionals) in a single step, we introduce Stateful Runtime Management in CaveAgent. Distinct from existing code-based approaches that remain text-bound and lack the support for external object injection and retrieval, CaveAgent injects, manipulates, and retrieves complex Python objects (e.g., DataFrames, database connections) that persist across turns. This persistence mechanism acts as a high-fidelity external memory to eliminate context drift, avoid catastrophic forgetting, while ensuring that processed data flows losslessly to downstream applications. Comprehensive evaluations on Tau2-bench, BFCL and various case studies across representative SOTA LLMs demonstrate CaveAgent’s superiority. Specifically, our framework achieves a 10.5% success rate improvement on retail tasks and reduces total token consumption by 28.4% in multi-turn scenarios. On data-intensive tasks, direct variable storage and retrieval reduces token consumption by 59%, allowing CaveAgent to handle large-scale data that causes context overflow failures in both JSON-based and CodeAct-style agents. Furthermore, the accessible runtime state provides programmatically verifiable feedback, establishing a rigorous foundation for future research in Reinforcement Learning (RL).

= Date: Jan 5, 2026

= Main Contact: Zhenglin Wan (vanzl@u.nus.edu), Jun Song (junsong@hkbu.edu)

1 Introduction

Large Language Models (LLMs) have demonstrated remarkable general knowledge acquisition and human-like reasoning capabilities, exhibiting exceptional performance across diverse natural language processing tasks. Building upon these foundational capabilities, tool-integrated reasoning (TIR) has enhanced LLM agent through reasoning to interact with external tools or application programming interfaces (APIs) in a multi-turn manner111In this paper, we refer to tool-use and function-calling interchangeably. (lu2023chameleon, shen2023hugginggpt, patil2024gorilla, qu2025tool), thereby substantially expanding their information access and solution space. This largely amplifies the landscape of LLM agents to variety of domains, such as scientific discovery (boiko2023emergent, bran2024chemcrow), mathematical problem-solving (gao2023pal, chen2022program), Web GUI navigation (zhou2023webarena, yao2022webshop) and Robotics (driess2023palme, brohan2023rt2).

Despite the promising landscape, the conventional protocol for tool use requires LLMs to conform to predefined JSON schemas and generate structured JSON objects containing precise tool names and arguments (qin2023toolllm, openai2023gpt4). For example, to retrieve stock data, the model must strictly synthesize a JSON string like {"tool": "get_stock", "params": {"ticker": "AAPL", "date": "today"}}, requiring exact adherence to syntax and field constraints. However, this approach exhibits significant limitations: 1) Flexibility: Agents are typically constrained by a rigid, iterative loop: executing a single tool call (or a parallel batch), serializing the output, and feeding the result back into the context for the subsequent generation. This introduces significant latency and context redundancy, resulting in suboptimal performance when addressing complex tasks that demand the sophisticated orchestration of sequential tool interactions (wu2023autogen, shen2023hugginggpt). 2) Hallucination: Achieving reliable tool-calling capabilities necessitates that the LLM outputs tool-related tokens with zero-shot precision (patil2024gorilla). However, in practice, relying on in-context learning to guide tool generation often suffers from severe hallucinations, such as inventing non-existent parameters or violating type constraints (patil2024gorilla, qin2023toolllm, li2023apibank). Crucially, errors in early turns propagate through the conversation, leading to cascading failures in multi-turn tasks (kim2023language). Moreover, adhering to JSON-Schema needs post-training LLMs which requires significant time and computational resources, and may even result in an LLM with lower intelligence levels than before post-training (JSON-post).

While recent works attempt to address this issue by empowering LLMs with code-based tool-use (wang2024executable, yang2024if), they predominantly adopt a process-oriented paradigm where the runtime state remains internalized and text-bound. The interaction forces a "textualization bottleneck”: variables are accessible to external systems only through text output, requiring serializing into text strings (e.g., printing a DataFrame) to communicate with the user (wang2024executable, yao2022react). This limitation fundamentally prohibits the direct input and output of structured, manipulatable objects, making it inefficient or impossible to handle complex non-textual data (e.g., large datasets, videos) (qiao2023taskweaver) and interact with down-stream tasks. To address these limitations:

We present CaveAgent, an open-source platform that pioneers the concept of Stateful Runtime Management in LLM agents. This marks a shift of code-based function calling paradigm from "process-oriented function-calling” to persistent "object-oriented state manipulation”. CaveAgent operates on a dual-stream architecture that enhances interaction between LLM agents and environments through two distinct streams: a semantic stream for reasoning and a runtime stream for state management and code execution. In this framework, the semantic stream remains lightweight, receiving only abstract descriptions of functions’ API and variables. It leverages the LLM’s inherent coding capabilities to generate code that manipulates the runtime stream—the primary locus of our stateful management. By injecting complex data structures (such as graph, dataframe, etc.) directly into the runtime as persistent objects, we achieve another form of context engineering: the agent manipulates high-fidelity data via concise variable references, decoupling storage from the limited context window to the persistent runtime. Specifically, any intermediate result (e.g., DataFrames, planning trees, or key metadata) can be stored in newly injected stateful variables and the agent will actively retrieve relevant variables for later use or downstream applications. This avoids catastrophic forgetting (catastrophic1, catastrophic2), enables efficient context compression and error-free recall for long-term memory where the runtime serves as an "external memory dictionary". Besides, this persistent environment further enables few-steps solution of complex logical dependencies by directly using code to interact with multiple logically inter-dependent tools, allowing the agent to compose intricate workflows (e.g., data filtering followed by analysis) in a few turns, thus avoiding the potential error and instability caused by multi-round function calling (multi-turn1, qin2023toolllm). Furthermore, the runtime’s transparency makes agent behavior fully verifiable, supporting checks on both intermediate programmatic states and final output objects of any data type. This capability creates a rigorous framework for Reinforcement Learning by enabling the generation of verifiable, fine-grained reward signals. Finally, CaveAgent supports lossless artifact handoff by returning native Python objects rather than text representations, and the extraction of manipulated Python objects for direct use in down-stream tasks such as UI rendering, visualization and structured validation. The runtime can be easily serialized and reloaded, providing a simple yet powerful mechanism for preserving the agent’s complete state across sessions and enabling true long-term memory and task continuity. This transforms the LLM from isolated text generator into an interoperable computational entity, seamlessly embedding within complex software ecosystems and automated decision-making frameworks.

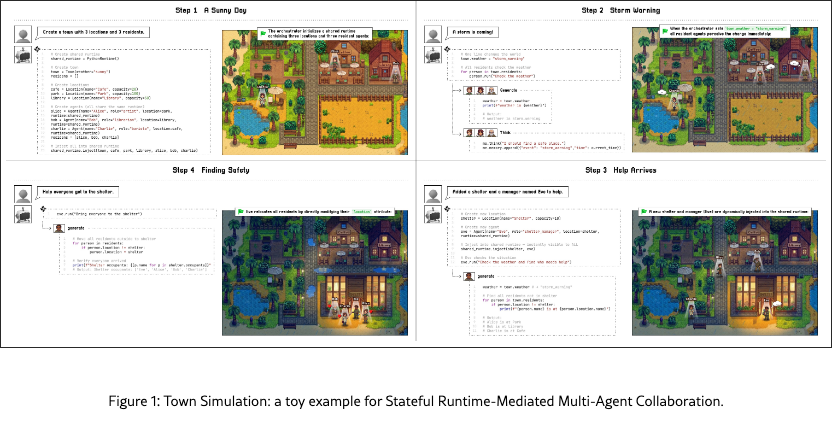

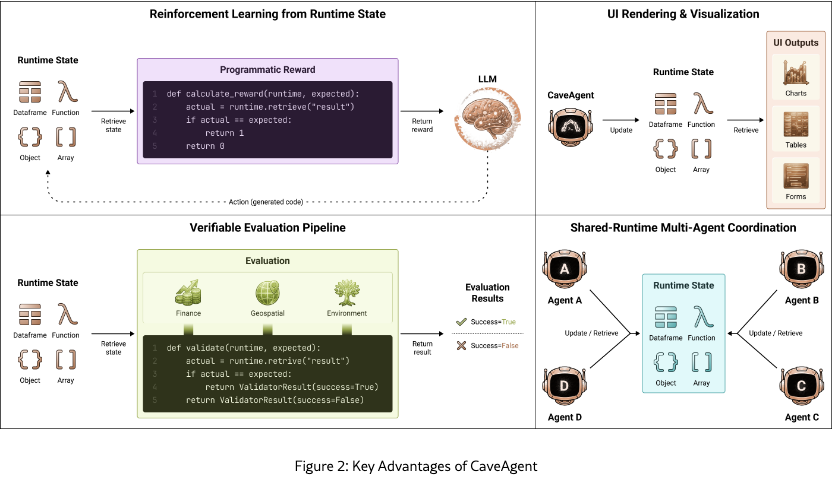

In addition to these insights, we found that the function calling paradigm in CaveAgent could potentially extends beyond single-agent capabilities to pioneer Runtime-Mediated Multi-Agent Coordination, as shown in Figure 1 and the right-bottom sub-figure of Figure 2. Unlike conventional frameworks where agents coordinate via lossy, high-latency text message passing (li2023camel, generative_agents), CaveAgent enables agents to interact through direct state manipulation. In this paradigm, a supervisor agent can programmatically inject variables into a sub-agent’s runtime to dynamically alter its environment or task context, effectively controlling behavior without ambiguous natural language instructions. Furthermore, multiple agents can operate on a unified shared runtime, achieving implicit synchronization: when one agent modifies a shared object (e.g., updating a global ’weather’ entity in a town simulation), the change is instantly perceivable by all peers through direct reference. This transforms multi-agent collaboration from a complex web of serialized dialogue into a precise, verifiable state flow, ensuring that large-scale coordination remains coherent and grounded (the details of Runtime-Mediated Multi-Agent Coordination can be found in Appendix E). We summarize our contribution as follows:

-

•

We introduce CaveAgent, a new function-calling paradigm that pioneers the concept of Stateful Runtime Management. This architecture marks a paradigm shift from process-oriented function calling to persistent, object-oriented state management. CaveAgent achieves a form of context compression and context-grounded memory recall via delegating context engineering to persistent runtime, eliminating the token overhead and precision loss inherent in textual serialization while enabling the few step solution of complex, logically interdependent tasks.

-

•

The framework’s programmatic inspectability provides deterministic feedback on intermediate states, establishing a rigorous foundation for future research in Reinforcement Learning with Verifiable Rewards (RLVR) on this paradigm without the need for subjective human annotation.

-

•

We conduct evaluations demonstrating CaveAgent’s tool use ability on standard benchmarks (e.g., Tau2Bench) and provides comprehensive case study across various domains to showcase the unique advantages of CaveAgent. Additionally, we identified the potential to extend the paradigm to enable Stateful Runtime-Mediated Multi-Agent Coordination and provided qualitative results, opening the opportunity for future research on this direction.

2 Background

In this section, we formally formulate the function-calling (tool-use) in LLMs. We consider an LLM agent parameterized by , tasked with solving a user query . The agent is equipped with a tool library . Each tool is defined by a tuple , representing the tool name, description, and parameter space, respectively. The problem is modeled as a multi-step decision process. At time step , given the context history , the agent generates a response. The history is defined as a sequence of interactions:

| (1) |

where denotes the internal reasoning (thought), denotes the tool action, and denotes the execution observation.

ReAct Paradigm

In the traditional ReAct paradigm (yao2022react), both reasoning and action are generated as contiguous natural language sequences from the model’s vocabulary . The generation probability is formalized as: , where represents tokens in the sequence . Crucially, the action in ReAct is a raw text string (e.g., "Action: Search[query]") that requires a heuristic parser to extract the executable function and parameters. Let be the raw text output. The effective action is obtained via: . This formulation suffers from hallucination and format errors, as the support of covers the entire vocabulary , meaning (patil2024gorilla, liu2023agentbench).

JSON-Schema Function Calling

To address the ambiguity of unstructured text generation, modern agents adopt JSON-Schema Function Calling (patil2024gorilla, qin2023toolllm). Here, the toolset is augmented with a set of structured schemas , typically defined in JSON Schema format. The reasoning process remains in natural language, but the action generation is transformed into a constrained decoding process. The model is conditioned explicitly on , and the action is no longer treated as free text, but as a structured object (a JSON object). To help the model output the JSON object correctly, we could utilizes In-Context Learning to internalize schema structures (toolformer). Crucially, special tokens (e.g., <tool>) are introduced to explicitly demarcate the reasoning phase from the action phase. While recent development in Agentic RL adopts Reinforcement Learning using composite reward signal to incentive the model to output correct JSON format and function calling parameter (coderl), this paper mainly focus on inference-time rather than training-time techniques.

Essentially, JSON-Schema function calling operates as a text-based serialization loop (yao2022react, automatedGPT). The process consists of three phases: (1) Context Serialization: The structured schema is flattened into a textual description and injected into the system prompt via context engineering; (2) String Generation: The LLM acts as a neural generator, predicting a string JSON payload based on textual instructions; and (3) Execution: An external middleware parses this string, executes the actual code, and serializes the execution result back into text to update the context window. This paradigm does not fundamentally deviate from the traditional context engineering framework of LLMs, suffering from inherent limitations such as context explosion, hallucination, and error propagation (packer2023memgpt, wang2023mint).

Code-based Function Calling

To address these limitations, recent works such as codeact (wang2024executable) utilize executable code as the media of function calling. However, current code agents suffer from architectural limitations. CodeAct essentially does not expose explicit APIs for external object injection and retrieval. Interaction is strictly mediated by the LLM via a "textualization" bottleneck, where intermediate states must be serialized into standard output (e.g., print) to be perceived by the user. For instance, as wang2024executable stated, when the agent requires external data for analysis, Codeact typically downloads the dataset via Python (e.g., pd.read_csv(url)). This approach is inherently inflexible: its interface boundary relies on text serialization for data ingestion, making it difficult to directly inject pre-existing Python objects such as in-memory DataFrames, trained models, or custom class instances without custom workarounds. Moreover, this reliance on text makes it challenging to handle of non-textual or high-dimensionality artifacts (e.g., raw video streams, large-scale databases), and exposes the risk of context explosion, distraction of LLM and hallucination (liu2024lost, packer2023memgpt).

In the subsequent section, we demonstrate how CaveAgent pioneers the Object-Oriented paradigm based on Python’s "everything is an object” philosophy by maintaining two paralleled context stream and delegating context management to a persistent Python runtime stream. Figure 3 shows the evolution path of paradigm shift in Agentic Tool Use.

3 CaveAgent: Stateful Runtime Management

3.1 Core Methodologies

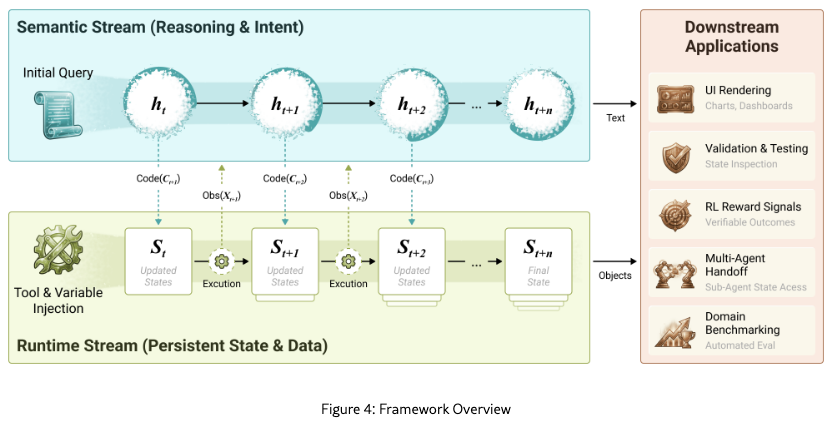

In this section, we present the design philosophy of CaveAgent. As illustrated in Figure 4, CaveAgent adopts a dual-stream architecture, maintaining two synchronized streams throughout the interaction lifecycle: a Semantic Stream for light-weight reasoning, and a Runtime Stream for stateful execution, observation and context engineering. This design fundamentally redefines the agentic interaction loop, shifting from stateless text-based serialization to a persistent, state-aware model.

We model the agent’s task as a sequential decision process over a horizon . At each turn , the agent receives a query or observation and must produce a response . Unlike traditional formulations where the entire state is re-serialized into , we introduce a latent runtime state (we call it "in-runtime context"). The system evolution is thus defined by:

| (2) | |||||

| (3) |

where represents the semantic history (we call it "in-prompt context") and is the executable code generated by the agent. The critical innovation lies in the decoupling of and : the semantic stream tracks intent and light-weight reasoning for code generation, while the runtime stream maintains all crucial data and execution state via the code generated by semantic stream.

The Runtime Stream:

The core engine of the runtime stream is a persistent Python kernel (specifically, an IPython interactive shell). We conceptualize each interaction turn not as an isolated API call, but as a cell execution in a virtual Jupyter notebook.

-

•

Persistent Namespace: The state comprises the global namespace , containing all variables, functions, and imported modules. When the agent executes code (e.g., x = 5), the modification to persists to . This allows subsequent turns to reference x directly without requiring the LLM to memorize or re-output its value.

-

•

Stateful Injection: Tools are not only described in text; they are injected into as live Python objects. This allows the agent to interact with stateful objects via calling tools that modify the object’s internal state across turns.

Notably, the runtime stream can assign values to new variables during the interaction process and inject them into the Persistent Namespace (in-runtime context). This enables heavy context in complex tasks, such as large DataFrames, graphs, or other intricate data structures, to be managed entirely by the Python runtime stream as stateful variables. Their values are thus preserved natively in persistent runtime memory without requiring repeated serialization into text, effectively eliminating the risk of hallucination that arises from lossy textual representations. Besides, the agent can inject and store crucial information (such as key reasoning chains and intermediate data analysis results) via new persistent variables into in-runtime context, retaining only a lightweight description and reference in its in-prompt context. Consequently, the runtime functions as an external memory dictionary, allowing the agent to actively retrieve this memory as native, lossless Python objects, thus achieving a form of context compression and avoiding catastrophic forgetting. This property is crucial, as it addresses persistent challenges in agentic tool use—specifically memory, dynamic decision-making, and long-horizon reasoning (bfcl). Meanwhile, this system also makes the manipulation of data objects and propagating them between multiple-turns much easier, no matter how complex the data structures are.

It is also notable that the programmatic state retrieval enables the extraction of manipulated Python objects for direct use in downstream applications. Unlike conventional agents that produce terminal text outputs requiring parsing and reconstruction, CaveAgent exposes native objects (DataFrames, class instances, arrays) with full type fidelity and structural integrity. This enables diverse integration pathways. For example:

-

•

UI components can bind directly to retrieved objects for exact data visualization, enabling real-time dashboards reflect to exact agent state.

-

•

RL pipelines can compute precise reward signals through programmatic state inspection rather than noisy text-based heuristics, automate the process of success/failure detection for trajectory labeling, and conduct credit assignment based on state analysis.

-

•

Validation frameworks can apply unit test assertions and schema verification against returned structures, enabling domain-specific benchmarking with programmatic correctness.

-

•

Multi-agent systems can pass objects directly between agents without serialization loss, share state synchronization across agent swarm and resolve dependency based on object availability (as discussed in detail at Appendix E).

The agent thus transforms LLMs from an isolated text generator into the operator of a stateful, interoperable computational component whose outputs integrate natively into broader software ecosystems and automated decision-making pipelines.

The Semantic Stream:

Parallel to the runtime stream, the semantic stream utilizes LLM as a brain to generate code to manipulate runtime. Besides, it is also responsible for:

-

•

Prompt Construction: Dynamically generating system instructions that describe the signatures of available tools in , without dumping their full state (which may be large) into the in-prompt context window.

-

•

Observation Shaping: Captures execution outputs and enforces a length constraint to prevent context explosion. This feedback mechanism actively teaches the agent to interact with the persistent state efficiently, prioritizing concise and crucial information over verbose raw dumps in the in-prompt context .

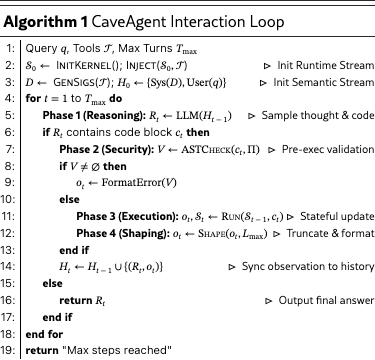

This dual-stream design solves the "Context Explosion" problem: massive data remains in the Runtime Stream (), while only the high-level reasoning and necessary summaries flow through the Semantic Stream (). The LLM effectively operates a remote control (code) to manipulate a complex runtime without needing to hold the runtime’s entire state in its working memory. Compared to traditional JSON-based function calling where larger models tend to parallelize tool calls for efficiency but fall short when there are inter-dependencies between tools (toolsandbox), CaveAgent enables dependency-aware parallelism, allowing agents to dispatch complex, interdependent tool chains in a few turns via executable code to guarantee both efficiency and correctness. Compared to traditional code-based function calling that adopts internalized runtime, CaveAgent opens the runtime as a bidirectional interface, allowing developers to inject arbitrary variables directly and retrieve structured, manipulatable objects of any type at any time and achieves true stateful interoperability. Algorithm 1 in Appendix A showcases the iteration loop of CaveAgent framework. Then, we demonstrate three core designs of CaveAgent beyond traditional JSON-based and code-based tool use.

3.1.1 Variable and Function Injection

To bridge the gap between large language models and executable environments, we introduce a unified abstraction for Variable and Function injection. CaveAgent treats Python objects and functions as first-class citizens within the runtime environment to ensure object-oriented interactions. This mechanism consists of two key components: metadata extraction for the semantic stream’s context and direct object injection into the runtime namespace.

Descriptive Abstraction

Each injectable entity is wrapped in a container that automatically extracts its metadata. For functions, this includes the signature, type hints, and docstrings; for variables, it includes the name, type, and an optional description. Formally, a function is represented as a tuple , where is the function name, is the signature derived from inspection, and is the documentation. Similarly, a variable is represented as , where is the type. This metadata is aggregated and injected into the system prompt, providing the model with a clear "API reference” of available capabilities without exposing implementation details or raw values. For example, an injected data processing object might be presented to the model as:

Namespace Injection

Critically, injection goes beyond mere description. Upon initialization, the runtime maps these entities directly into the namespace of the underlying execution engine (e.g., IPython). This means that if a function add or an object processor is injected, they become immediately available as global symbols in the execution environment. This design enables Object-Oriented Interaction and Stateful management. Instead of stateless function calls (e.g., tool: "sort", args: {data: ...}), the model can invoke methods on stateful objects directly (e.g., processor.process(data)). This significantly enhances composability, as the model can chain method calls and manipulate object attributes naturally, mirroring standard programming practices rather than rigid API request-response cycles.

After variable and function injection, CaveAgent interacts with the environment via executable Python programs leveraging native Python syntax for robust parsing and utilizing control flow (loops, conditionals) with stateful data passing to handle multi-step logic. Unlike text-based paradigms, CaveAgent allows for lossless manipulation of complex data structures throughout the interaction. Consequently, the agent delivers the final output not as a textual approximation, but as a valid, native Python object guaranteed to match the expected type, enabling seamless integration with downstream applications.

3.1.2 Dynamic Context Synchronization

While the dual-stream architecture decouples reasoning from state storage, effective collaboration requires a regulated information flow between the Semantic Stream and the Runtime Stream. We implement a dynamic synchronization mechanism to ensure the agent remains aware of the runtime state without overwhelming its context window.

In our framework, the Semantic Stream is "blind" to the Runtime Stream by default. Visibility is achieved explicitly via execution outputs. To inspect the state (e.g., the content of a variable), the agent must generate code to print a summary (e.g., print(df.head())). This design enforces an Active Attention Mechanism: the agent consciously selects which part of the massive runtime state is relevant to the current reasoning step, pulling only that slice from the runtime, the external memory, into the token context.

To prevent "Context Explosion" caused by accidental verbose outputs (e.g., printing a million-row list), we introduce an Observation Shaping layer. The runtime captures standard output and subjects it to a length constraint function .

| (4) |

When the output exceeds , instead of truncating silently, the system injects a specific meta-instruction prompting the agent to revise its code (e.g., "Output exceeded limit, please use summary methods"). This feedback loop teaches the agent to interact with the persistent state efficiently, favoring information which is concise and most-relevant, over verbose raw data dumps.

3.1.3 Security Check via Static Analysis

CaveAgent mitigates code execution risks via Abstract Syntax Tree (AST)-based static analysis, enforcing security policies without compromising flexibility. We parse code into a tree and validate it against a policy , where . The modular rule set includes (example):

-

•

ImportRule: Blocks unauthorized modules (e.g., os, subprocess).

-

•

FunctionRule: Prohibits dangerous calls (e.g., eval(), exec()).

-

•

AttributeRule: Prevents sandbox bypass via internals (e.g., __builtins__).

Structured Error Feedback. Violations trigger structured observations rather than system crashes. For instance, a SecurityError is returned to the semantic stream, enabling the agent to self-correct (e.g., replacing eval() with safe tools) and ensuring interaction continuity.

4 Experiments

In this section, validate CaveAgent by answering four questions:

-

•

[Q1.] Can CaveAgent perform on par with or surpass standard function-calling paradigms on widely-used benchmarks involving basic function-calling tasks? This is to showcase the basic function calling capabilities of CaveAgent.

-

•

[Q2.] Can CaveAgent successfully perform state management across multi-turns correctly and efficiently?

-

•

[Q3.] How token-efficient is CaveAgent compared to traditional JSON-based and Codeact style function calling?

-

•

[Q4.] How does CaveAgent adapt to complex scenarios that require manipulating complex data objects? This is to showcase CaveAgent’s unique advantages.

4.1 [Q1] Standard Function Calling Benchmarks

To verify the CaveAgent’s basic function-calling capabilities on standard function-calling tasks, we employ two widely-adopted benchmarks in Agentic tool use: Tau2-bench (yao2024tau) and the Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard (BFCL) (bfcl).

Models.

We evaluate a wide spectrum of State-of-the-Art (SOTA) LLMs to benchmark our performance, ensuring a comprehensive coverage of different architectures (e.g., dense vs. MoE) and model scales. The model suite includes:

-

•

DeepSeek-V3.2: The latest iteration of the DeepSeek series, featuring a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture with 685B parameters (37B active). Setting: Temperature set to to ensure stable code generation.

-

•

Qwen3 Coder 30B: A specialized code-centric model built on the Qwen3 architecture. It utilizes a highly efficient MoE design with 30B parameters (3B active). Setting: Configured with a temperature of for stable output generation.

-

•

Kimi K2 0905: A large-scale MoE model with 1000B parameters (32B active), designed for long-context interactions. Setting: We adopt the official recommended temperature of .

-

•

Claude Sonnet 4.5: The SOTA model of Claude-series from Anthropic. Setting: Temperature is set to for stable code generation.

-

•

GPT-5.1: An evolution of the GPT-series. Setting: We utilize the default temperature of , as this is the only supported value for the current snapshot.

-

•

Gemini 3 Pro: Known for its massive context window and native multimodal reasoning. Setting: Configured with "Low thinking” reasoning mode and a temperature of , adhering to official recommendations.

For each backbone model, we conduct a comparative analysis between its native function-calling mechanism and our proposed CaveAgent framework. Crucially, within the CaveAgent workflow, the LLM is repurposed solely as a text generation engine, referred to as the semantic stream in our framework, bypassing its internal function-calling modules. We run each model using the standard API offered by the model provider.

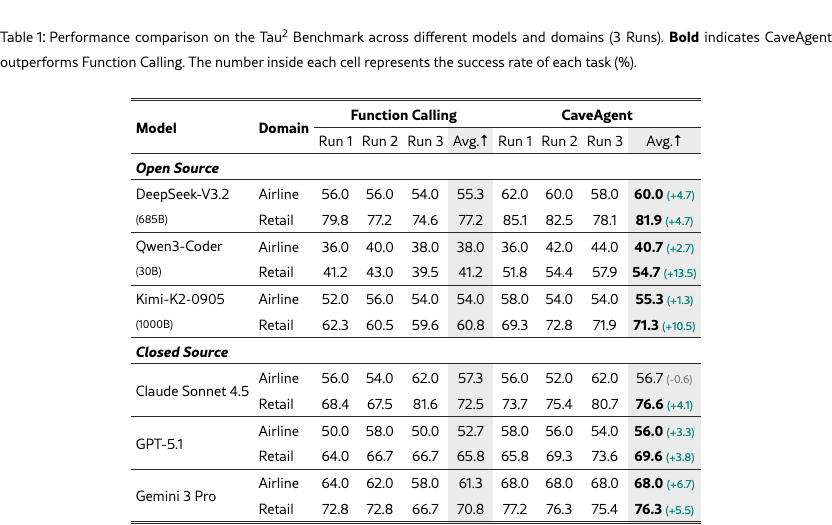

4.1.1 Results on Tau2-bench

Tau2-bench (yao2024tau) is a comprehensive benchmark designed to evaluate the dynamic tool-use capabilities of LLM-based agents in realistic, multi-turn conversational scenarios. Unlike static evaluation sets that focus on single-turn intent detection, Tau2-bench necessitates that the agent interacts with a simulated user to achieve complex goals (e.g., modifying a flight reservation or processing a retail refund) while maintaining consistency across multiple turns. Following the original Tau2-bench paper, we focus on two primary domains within the benchmark: Airline and Retail. These domains are challenging since they require the agent to accurately track user constraints, database states, and policy regulations throughout the dialogue history.

Experimental Setup.

To ensure a rigorous comparison, we strictly follow the evaluation protocols of Tau2-bench. Specifically, we utilize DeepSeek V3 as the user simulator for all experiments to generate diverse and coherent user responses. To mitigate variance in generation, each model is tested three times for each domain. The reported results represent the respective scores and average scores of these three independent runs.

Evaluation of CaveAgent.

Since CaveAgent executes Python code rather than JSON tool calls, we employ runtime instrumentation to capture function invocations. Wrapper functions intercept each function call, recording function names and arguments before delegating to the underlying implementation. The captured invocation sequence is compared against ground-truth actions using identical evaluation criteria applied to JSON-based agents, ensuring a fair cross-paradigm comparison based on which functions were called with what arguments.

Performance Analysis.

The quantitative results on Tau2-bench are summarized in Table 1. The key insights include: (1). CaveAgent consistently outperforms the standard JSON-based function calling paradigm across 11 out of 12 experimental settings, covering both open-source and proprietary models ranging from 30B to over 1000B parameters. Significant improvements are observed in most SOTA models like DeepSeek-V3.2 and Gemini 3 Pro (averaging +5.3% and +6.1% respectively), demonstrating that our framework breaks the performance ceiling of even the most capable semantic reasoners by offloading state management to a deterministic and error-free code runtime. (2). CaveAgent shows superiority in state-intensive scenarios. We observed that the performance advantage is markedly amplified in the Retail domain compared to Airline. Retail tasks in Tau2-bench typically involve complex transaction modifications and policy checks, which require maintaining high-fidelity state consistency across turns. The standard paradigm suffers from serialization overhead here, leading to hallucinations. In contrast, CaveAgent achieves double-digit gains in Retail for models like Qwen3 and Kimi K2. This validates our hypothesis that Stateful Runtime Management effectively eliminates errors caused by the repetitive text-based serialization of complex data objects (e.g., shopping carts or refund policies). We provided a detailed agent trajectory analysis about the reason of CaveAgent’s outstanding performance in Retail tasks in Appendix F.1. (3). CaveAgent unlocks the potential in code-centric models. Most notably, the smaller, code-specialized Qwen3-Coder (30B) exhibits the largest relative improvement (+13.5% in Retail), enabling it to rival the performance of significantly larger generic models. This confirms that CaveAgent effectively leverages the inherent coding proficiency of LLMs. By decoupling the semantic stream from the runtime stream, our approach allows code-centric models to focus on logic generation rather than struggle with verbose context tracking, thereby maximizing the utility of limited parameters.

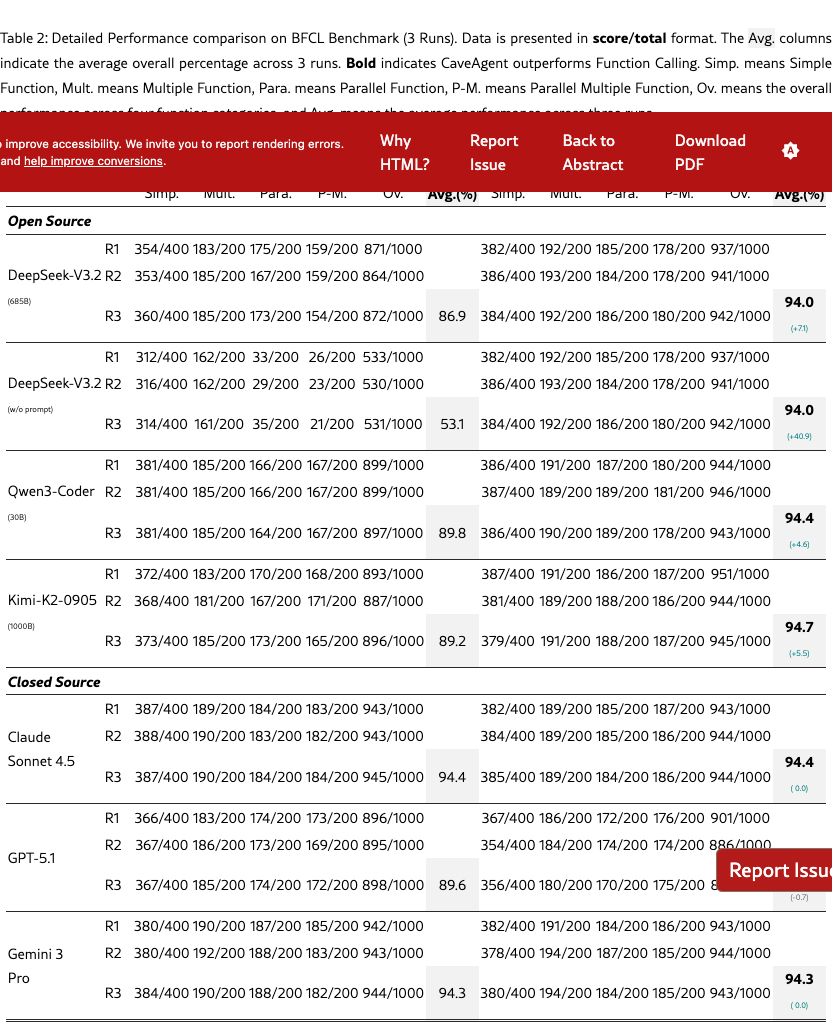

4.1.2 Results on BFCL

While Tau2-bench evaluates the capability of maintaining long-term state, it is equally critical to assess the agent’s precision in atomic function executions. To this end, we employ the Berkeley Function Calling Leaderboard (BFCL) (bfcl), a widely recognized benchmark for quantifying the accuracy of LLM tool invocation.

Benchmark Overview.

BFCL constructs a rigorous evaluation environment consisting of approximately 2,000 question-function-answer pairs derived from real-world use cases. The dataset is designed to test models across varying levels of complexity. Key evaluation categories include:

-

•

Simple Function: Represents the fundamental evaluation scenario where the model is presented with a single function definition and must generate a unique invocation with correct arguments and results.

-

•

Multiple Function: Assesses the model’s selection capability. The model is provided with a candidate set of 2 to 4 function definitions and must identify and execute the single most appropriate function that addresses the user’s query, filtering out irrelevant tools.

-

•

Parallel Function: Evaluates the ability to execute concurrent/parallel actions within a single turn. The model must decompose a complex user query (spanning one or multiple sentences) into multiple distinct function calls, invoking them simultaneously to optimize efficiency.

-

•

Parallel Multiple Function: The most challenging category, combining tool selection with parallel execution. The model is confronted with a larger pool of function definitions and must determine both the correct subset of tools to use and the frequency of their invocation (zero or more times) to fully resolve the request.

Notably, we use Executable Evaluation (Functional Correctness), rather than Abstract Syntax Tree (AST) evaluation since AST is not directly applicable in our CaveAgent framework due to the lack of explicit JSON schema. We execute the generated code in a controlled environment and compares the execution result against the ground truth. This validation ensures that the function call triggers the correct behavior in real-world applications.

Performance Analysis.

The results in Table 2 highlight the atomic precision of CaveAgent in single-turn scenarios. Key observations include: (1). The results for DeepSeek-V3.2 (w/o prompt) reveal a critical insight. We hypothesize that due to its training emphasis on reasoning regarding tool dependencies (liu2025deepseek), DeepSeek-V3.2 exhibits a strong inductive bias toward sequential execution, causing it to fail in parallel-calling scenarios under the standard JSON paradigm (53.1% accuracy). To ensure a fair comparison, we added explicit prompting to the system prompt of DeepSeek V3.2 to "force” parallel execution. In stark contrast, CaveAgent achieves SOTA performance (94.0%) without any prompt intervention. This demonstrates a unique advantage of our paradigm: by utilizing Python code, CaveAgent naturally supports parallel execution (e.g., via independent lines of code) while simultaneously preserving the capacity to reason about inter-tool dependencies, resolving the conflict between reasoning depth and execution parallelism that standard JSON approaches struggle. (2). The 30B parameter Qwen3-Coder, when equipped with our framework, achieves a 94.4% average score, outperforming the much larger proprietary GPT-5.1 (89.6%) and matching Claude Sonnet 4.5. We attribute this to that CaveAgent unlocks more potential of small LLMs via effectively leveraging the inherent coding proficiency of LLMs.

For most SOTA models like Claude Sonnet 4.5 and Gemini 3 Pro, CaveAgent performs on par with the standard baseline (94.3%), with negligible variance. We attribute this plateau to benchmark saturation. Current SOTA models have likely reached the upper limit of the BFCL dataset, where remaining errors stem from ambiguous natural language queries or ground-truth noise rather than model incapacity. Since BFCL focuses strictly on single-turn intent detection without the complexity of state maintenance, the "ceiling" is hit relatively quickly. It is important to emphasize that Tau2-bench and BFCL serve primarily to validate the basic function-calling capabilities of CaveAgent. However, the true superiority of our proposed paradigm lies in tasks demanding more advanced tool-use—specifically, the manipulation of complex data objects over long-horizon tasks. Consequently, existing benchmarks are insufficient to fully capture the stateful management capability of CaveAgent. In the following section, we utilize our hand-crafted cases to provide a deeper and more rigorous assessment of CaveAgent’s capabilities in long-horizon stateful management.

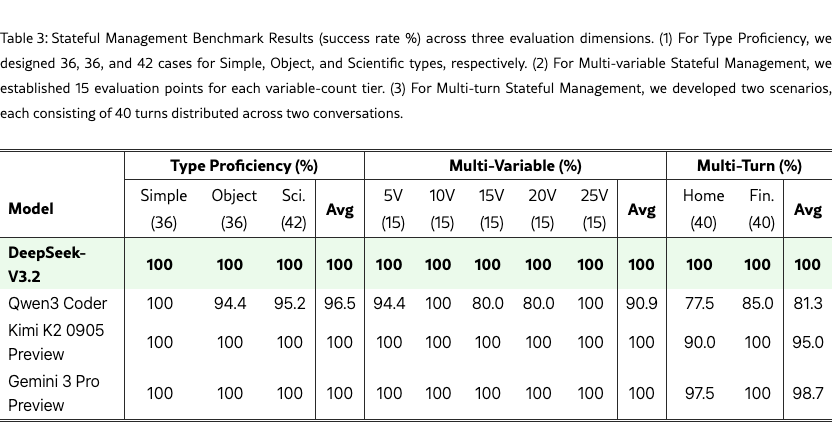

4.2 [Q2] Case Study: Stateful Management

To evaluate CaveAgent’s stateful runtime management capabilities, we design a benchmark targeting multiple complementary dimensions of state manipulation that existing function-calling benchmarks fail to address. The benchmark tests an agent’s ability to read, modify, and persist variables across multiple conversational turns. We divide the measurement of stateful management into three categories: Python type proficiency, capability of multi-variable manipulation, and robustness in multi-turn, long-horizon interaction. A unifying design principle is programmatic validation: rather than parsing text outputs or relying on heuristic matching, we directly inspect runtime state after execution, verifying exact values, object attributes, and data structure contents against ground-truth expectations. This enables precise, unambiguous evaluation and demonstrates a key advantage of CaveAgent’s architecture: agent behavior becomes programmatically verifiable, opening pathways for automated evaluation and reinforcement learning with accurate reward signals.

For each dimension, we manually curate multiple test cases, each consisting of multiple natural language queries and an initial variable state, where the queries are linearly dependent. The agent sequentially manipulates the variable according to the queries, after which we retrieve the resulting variable for validation. A query is considered successful if the value of the output variable aligns with our expectations (see Appendix D for the details about the test cases). To isolate core state management capabilities, we craft queries with unambiguous requirements and explicit expected outcomes, ensuring that failures reflect genuine limitations in state tracking rather than instruction misinterpretation. Multiple queries per case further measure long-horizon state persistence and numerical precision across multi-step operations. For each dimension, we select four models to conduct this experiment: QWen3 Coder, Kimi K2 0905, Deepseek V3.2 and Gemini3 Pro. We report the success rate computed by the number of successful queries/total number of queries, as shown in Table 3.

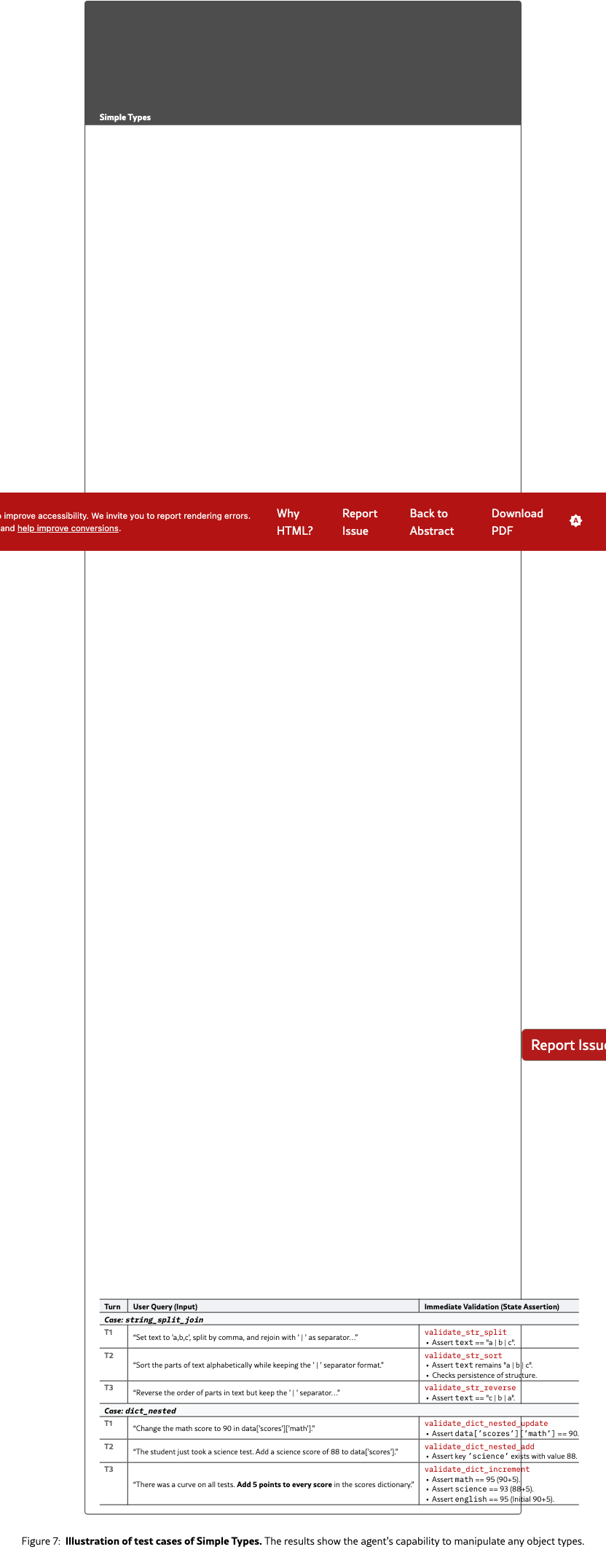

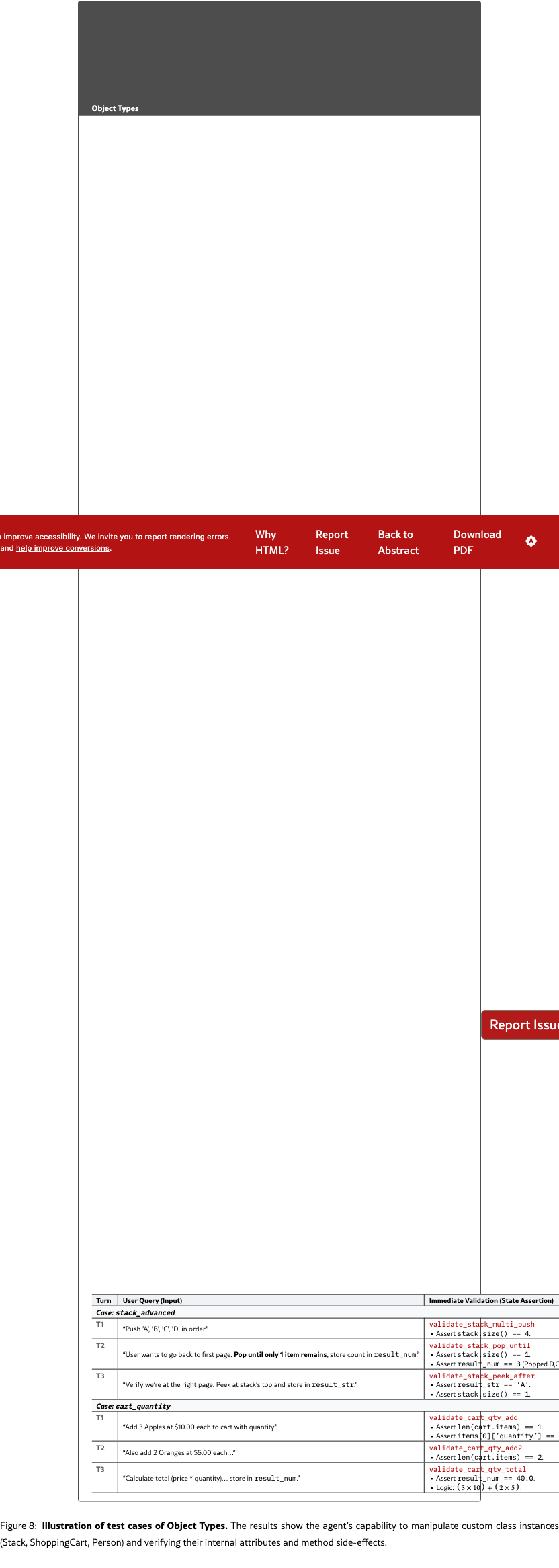

4.2.1 Type Proficiency

Type Proficiency aims to evaluate an agent’s ability to manipulate variables across a spectrum of Python types:

-

•

Simple Types: Fundamental operations on Python primitive types including integers, floating-point numbers, strings, booleans, lists, and dictionaries.

-

•

Object Types: Interaction with user-defined class instances, including attribute access and modification, method invocation, and state tracking across object lifecycles.

-

•

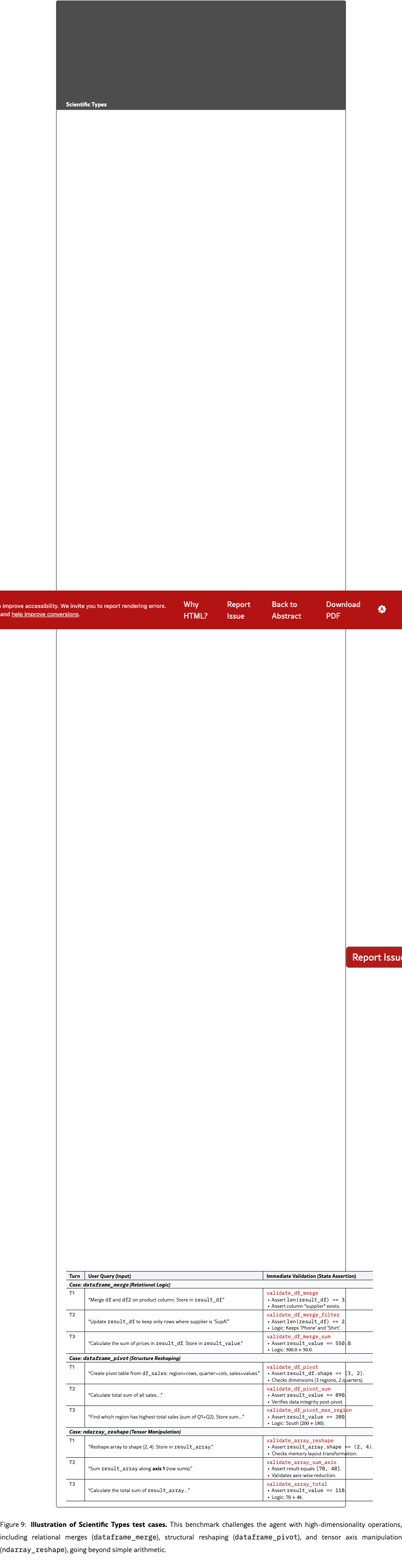

Scientific Types: Proficiency with data science primitives commonly used in computational workflows: pandas DataFrames, pandas Series, and NumPy ndarrays. Operations include column creation, filtering, sorting, element-wise transformations, aggregations, and cross-type interactions (e.g., storing array computations as DataFrame columns).

The results yield uniformly high scores (96.5%–100%), validating that code-based manipulation of complex types—including DataFrames, ndarrays, and custom objects—is tractable for current LLMs.

4.2.2 Multi-Variable

The Multi-Variable benchmark evaluates how state management accuracy changes when number of variables scale up.

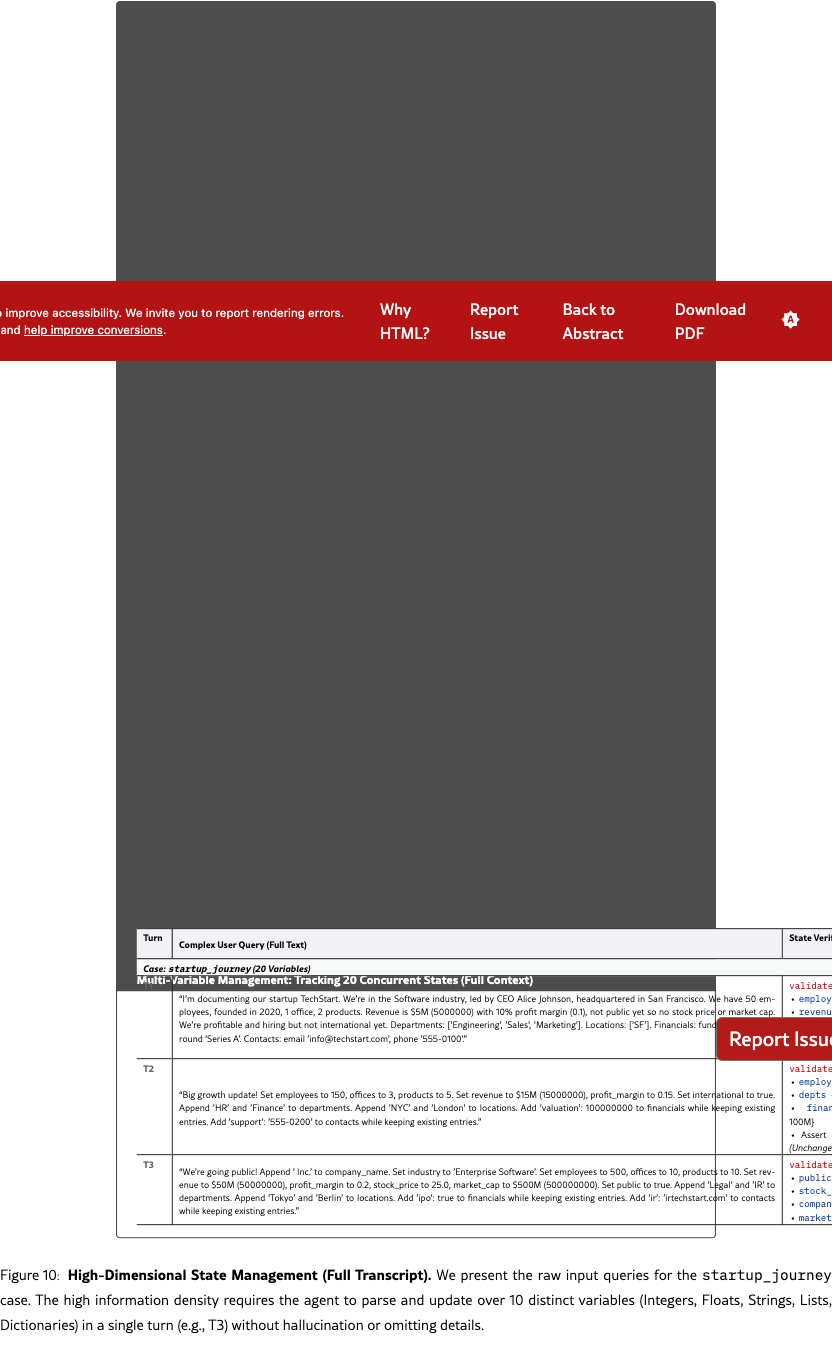

The benchmark comprises five tiers with 5, 10, 15, 20, and 25 concurrent variables, systematically testing the agent’s working memory capacity and ability to perform coordinated state manipulation. Each tier contains 5 multi-turn conversations, and each conversation contains 3 turns, yielding 15 evaluation points per variable tier. The results show no systematic degradation as variable count scales to 25, with top models maintaining 100% accuracy throughout, demonstrating that concurrent state management scales effectively within CaveAgent’s architecture.

4.2.3 Multi-Turn

The Multi-Turn benchmark assesses an agent’s ability to read, modify, and persist variables across extended interactions—a critical capability for real-world deployments requiring the tracking of cumulative state changes. The benchmark comprises two domain-specific scenarios, each spanning 40 turns across two conversations:

-

•

Smart Home: Simulates a home automation environment where the agent manages devices (e.g., lighting, thermostats) via natural language. This scenario tests the agent’s ability to interpret intent and maintain device state consistency as commands accumulate.

-

•

Financial Account: Simulates banking operations such as transfers and inquiries. This scenario specifically targets numerical precision—ensuring calculation accuracy over multi-step operations—and stateful reasoning within a growing transaction history.

Collectively, these scenarios evaluate long-horizon state persistence, measuring whether the agent can reliably modify and track program state without drift as the conversation length increases. The results reveal the most meaningful differentiation between models. Long-horizon state persistence across 40 turns proves challenging: while DeepSeek-V3.2 maintains perfect accuracy, other models exhibit degradation, particularly on Smart Home scenarios requiring object state consistency. This suggests that accumulated state tracking over extended interactions remains the frontier capability for stateful agents. The consistently high accuracy across top models validates our central thesis: when LLMs interact through code with persistent runtime state, reliable and verifiable agent behavior becomes achievable. Notably, we restrict this evaluation to CaveAgent, as the fine-grained programmatic verification of Python objects is fundamentally incompatible with the text-based outputs of the JSON function-calling paradigm. Nevertheless, the near-perfect performance exhibited by CaveAgent independently substantiates the robustness of our stateful management.

4.3 [Q3] Token Efficiency Study

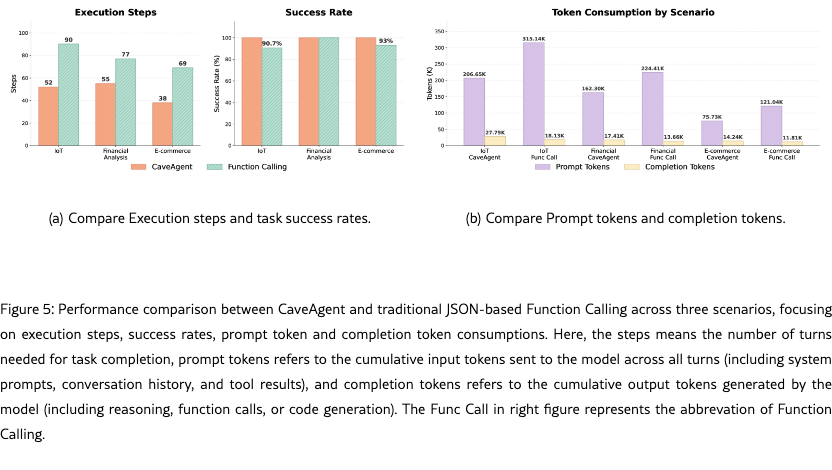

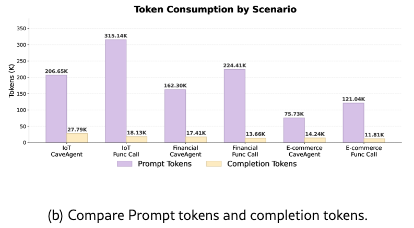

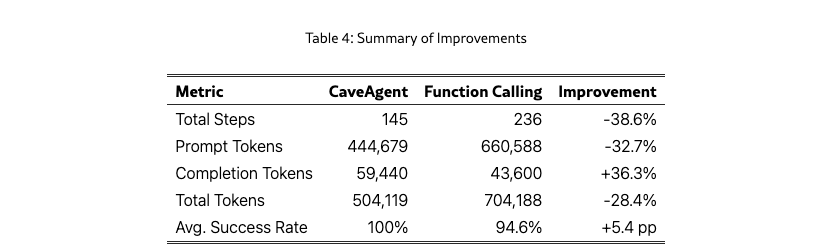

As a complementary experiment, we evaluate CaveAgent’s advantages in context engineering and token efficiency against traditional JSON-based function calling. We benchmark CaveAgent across three domains: IoT device control, financial portfolio analysis, and e-commerce operations. This benchmark specifically targets scenarios requiring logically interdependent tool operations, creating "check → decide → act" cycles where multiple tool calls depend on prior results. We evaluated both methods using DeepSeek V3.2, measuring success rate, execution steps, and token consumption to isolate and quantify the efficiency gains attributable to the architectural shift from iterative JSON dispatching to native code generation.

Figure 5 shows the full results of this study, and Table 4 summarizes the performance improvement by comparing the summed performance metrics across three domains. The results demonstrate that CaveAgent achieves 28.4% lower total token consumption (504K vs. 704K) while improving task success rate from 94.6% to 100%. The efficiency gain stems from reducing interaction turns. Traditional function calling requires separate request-response cycles for each dependent operation, causing prompt tokens to accumulate as conversation history grows with each turn. CaveAgent instead generates Python code that resolves multiple dependencies in a single execution, reducing total steps from 236 to 145 and consequently cutting prompt tokens by 32.7%. More importantly, the Stateful Management property of CaveAgent naturally reduces the token overhead in multi-turn interaction. This is because CaveAgent manipulates persistent objects via variable references rather than repeatedly serializing full data states into text, as required by stateless process-oriented paradigms.

Notably, CaveAgent consumes 36.3% more completion tokens, since Python code with loops and conditionals is more verbose than JSON schemas. However, prompt tokens dominate overall consumption and accumulate across turns, while completion tokens only account for very small proportion of total token consumption.

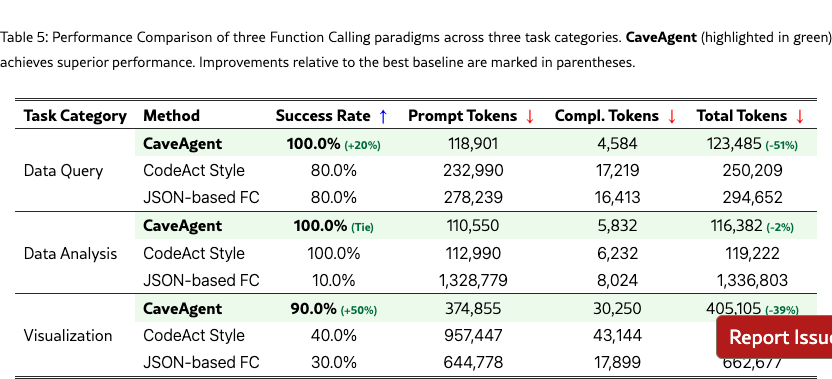

4.4 [Q4] Case Study: Data-intensive Scenario

To assess the practical benefits of stateful runtime management, we evaluate three agent architectures on a data-intensive benchmark comprising 30 tasks across data query, statistical analysis, and visualization. The benchmark uses stock market data from Apple and Google (2020–2025, Yahoo Finance, retrieved from https://finance.yahoo.com). To ensure consistency, all three task categories were equipped with identical data retrieval functions. CodeAct Style replicates standard code-execution agent behavior by disabling CaveAgent’s variable injection and retrieval. JSON-based Function Calling operates without code execution, relying solely on tool outputs fed back to the model. The results are shown in Table 5.

Data Query Tasks

CaveAgent achieved 100% accuracy while consuming only 123K tokens by storing query results directly in runtime variables, thereby bypassing prompt context accumulation. In contrast, CodeAct Style (80%, 250K tokens) and Function Calling (80%, 295K tokens) both required serializing complete datasets into the conversation history, either through printed output or tool responses, resulting in context overflow failures on high-volume queries. Notably, both baseline methods failed on identical tasks involving large result sets that exceeded the model’s context limit.

Data Analysis Tasks

For tasks requiring statistical computation (e.g., volatility, correlation, Sharpe ratio), CaveAgent and CodeAct Style both achieved 100% accuracy with comparable token consumption ( 116–119K), demonstrating that code execution is essential for programmatic analysis. However, Function Calling achieved only 10% accuracy while consuming over 1.3M tokens. Without code execution capabilities, the model could only succeed on a trivial counting task; all computational tasks failed as the model attempted to infer statistics from raw data rather than compute them programmatically.

Visualization Tasks

These tasks required generating ECharts configurations containing both chart specifications and underlying data arrays. CaveAgent maintained 90% accuracy (405K tokens) by retrieving computed chart data from runtime variables without context serialization. CodeAct Style achieved 40% accuracy but consumed approximately 1M tokens, as generated visualizations must be printed to the conversation for output extraction. Function Calling achieved only 30% accuracy (662K tokens)—lower than CodeAct despite fewer total tokens—because earlier context overflow caused complete failures before task completion.

Discussion

These findings demonstrate that stateful runtime management provides substantial efficiency gains for data-intensive agent tasks. By decoupling intermediate computational state from the prompt context, CaveAgent avoids the token accumulation that causes context overflow in conventional architectures. This advantage becomes increasingly crucial as task complexity and data volume scale, suggesting that persistent runtime environments represent a promising direction for building robust agentic systems capable of handling real-world data processing workloads.

5 Conclusion

We present CaveAgent, a novel framework that transforms LLM tool use from stateless JSON function calling to persistent, object-oriented stateful runtime management. CaveAgent enables agents to maintain high-fidelity memory of complex objects and execute sophisticated logic via Python code. Experiments on Tau2-bench show that this approach significantly outperforms SOTA baselines in multi-turn success rates (+10.5%) and token efficiency. Crucially, the programmatic verifiability of the runtime state provides a rigorous ground for future advancements in Reinforcement Learning and runtime-mediated multi-agent coordination, marking a critical step towards more reliable and capable autonomous agents. Qualitative case studies are provided in Appendix F.

6 Related Work

6.1 Tool Learning & Instruction Following (JSON-centric Paradigm)

The foundational approach to equipping Large Language Models (LLMs) with agency has relied on a "Classification-Slot Filling” paradigm, where models interface with external environments via structured data formats, predominantly JSON. Seminal works such as ToolLLM (qin2023toolllm) and Gorilla (patil2024gorilla) demonstrated that LLMs could be fine-tuned to navigate massive API indices and mitigate hallucinations by strictly adhering to predefined schemas. This structured interaction model was further formalized by industry standards like GPT-4 Function Calling and adopted by agentic frameworks such as ReAct (yao2022react) and the JSON mode of AutoGen (wu2023autogen), which orchestrate reasoning through iterative schema population. Nevertheless, the JSON-centric paradigm imposes severe architectural constraints. First, JSON is inherently a static data interchange format lacking native control flow; it cannot represent loops or conditional logic, forcing agents into expensive, multi-turn interactions to execute complex workflows (wang2024executable). Second, the verbose syntax of JSON introduces significant token overhead, resulting in low information density and high latency (wang2024executable). Finally, the rigidity of schema enforcement creates a fragility trade-off, where complex nested structures increase the probability of syntax errors and hallucination (patil2024gorilla).

6.2 Code as Action & Programmatic Reasoning

Recognizing the limitations of static schemas, recent research has explored "Code as Action” paradigm, where executable code (primarily Python) serves as the unified medium for reasoning and tool invocation. wang2024executable challenged the JSON-Schema convention with CodeAct, proposing executable Python code as a unified representation for both reasoning and action. Their work demonstrated that code-based interactions reduce multi-turn overhead by up to 30% compared to JSON-based methods and improve task success rates by 20% on benchmarks like M3ToolEval. This shift utilizes the Turing-complete nature of code to naturally express complex logic, loops, and variable dependencies that are cumbersome in JSON. This paradigm extends to domain-specific reasoning. suris2023vipergpt introduced ViperGPT, which composes vision modules into executable subroutines to solve visual queries, rendering the reasoning process interpretable. Similarly, chen2022program and gao2023pal proposed Program of Thoughts (PoT) and Program-aided Language Models (PAL), respectively. These frameworks decouple computation from reasoning by delegating arithmetic and symbolic logic to a Python interpreter, thereby mitigating the calculation errors common in pure language models. The efficacy of these methods is further amplified by code-optimized models such as DeepSeek-Coder-V2 (zhu2024deepseek), which exhibit superior performance in following complex programmatic instructions.

6.3 Context Management & Stateful Architectures

The constraints of LLM context windows have necessitated advanced memory management strategies. packer2023memgpt introduced MemGPT, which implements an OS-inspired virtual context management system, organizing memory into tiers (main vs. external) to handle long-horizon tasks. Similarly, qiao2023taskweaver proposed TaskWeaver, a code-first framework that attempts to maintain stateful execution for data analytics by preserving data structures like DataFrames across turns. However, existing approaches largely rely on Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) or textual summarization to manage context. These methods are inherently lossy: converting complex runtime objects (e.g., high-dimensional matrices, class instances) into text or vector embeddings strips them of their structural integrity and executable properties. CaveAgent addresses this by proposing Runtime-based Context Compression. Unlike prior work that externalizes state to vector stores, we utilize Variable Injection to treat the Python runtime itself as a high-fidelity external memory. This allows arbitrary variables to be persisted in their native object form, maintaining full manipulability without the overhead of re-tokenization or the information loss associated with serialization.

6.4 Multi-Agent Coordination Mechanisms

Research into multi-agent systems has focused on structuring collaboration through natural language communication. li2023camel proposed CAMEL, a role-playing framework that facilitates autonomous cooperation via communicative agents. Building on this, qian2023chatdev introduced ChatDev, which organizes agents into a "chat chain" following a waterfall software development model, while hong2023metagpt developed MetaGPT, which encodes Standardized Operating Procedures (SOPs) into agent prompts to streamline complex workflows. However, these frameworks predominantly rely on text-based message passing for coordination. This architecture introduces a critical serialization bottleneck: transferring complex state (e.g., a trained machine learning model or a processed dataset) between agents requires converting it into natural language descriptions or intermediate files, leading to high latency and potential ambiguity. CaveAgent overcomes this via Runtime-Mediated State Flow. By leveraging the shared variable space established in our runtime architecture, agents collaborate by directly injecting and retrieving variables. This shifts the coordination paradigm from "communication by talking" to "communication by shared state," enabling atomic, lossless, and zero-latency information exchange.

7 Acknowledgment

We thank Rui Zhou, a professional UI designer affiliated with Hong Kong Generative AI Research & Development Center, HKUST, for his professional contributions to the figure design of this paper.

Appendix

Appendix A Pseudo Code

Algorithm 1 shows the general workflow of CaveAgent.

Appendix B What Happens in Semantic Stream

The following sections detail the exact prompt templates used to instruct the Semantic Stream in CaveAgent to help readers understand what happens in this stream. The system prompt is dynamically constructed by combining the Agent Identity, Context Information (functions, variables, types), and specific Instructions.

B.1 System Prompt Construction

The full system prompt is composed using the following template structure. The placeholders (e.g., {functions}) are populated at runtime with the specific tools and variables available in the current environment.

Below are the default values for the key components referenced in the template above.

B.2 Context Injection Format

Examples of how context is formatted for the LLM.

B.3 Runtime Feedback Prompts

The agent operates in a closed feedback loop. After each code execution step, the runtime environment captures the output (stdout or errors) and constructs a new user message to guide the agent’s next action.

B.3.1 Standard Execution Output

This prompt is used when code executes successfully. It provides the standard output and explicitly reminds the agent that the variable state has been preserved.

B.3.2 Error Handling & Constraints

The system includes specific templates for handling edge cases, such as context window limits and security violations.

Output Length Exceeded: Used when the code generates excessive output (e.g., printing a massive DataFrame), prompting the agent to summarize instead.

Security Violation: Used when the static analysis security checker blocks unsafe code (e.g., os.system).

Appendix C What Happened in Runtime Stream

While the Semantic Stream governs the agent’s reasoning and planning, the Runtime Stream serves as the system’s execution engine and persistent memory. This stream operates as a dedicated Python kernel where the actual “work” of the agent (data manipulation, tool invocation, and state transitions) occurs. The interaction between the two streams follows a strict chronological topology, synchronized through an interleaved exchange of code instructions and execution feedback.

C.1 Environment Initialization via Injection

The runtime lifecycle begins not with an empty state, but with Context Injection. Before the reasoning cycle commences, the user (or the system orchestration layer) initializes the runtime environment by injecting native Python objects directly into the global namespace.

-

•

Function Injection: Tool definitions are loaded as executable Python callables. Unlike RESTful API wrappers, these are native functions that can be inspected and invoked directly.

-

•

Variable Injection: Domain-specific data—such as complex DataFrames, graph structures, or class instances—are instantiated within the “memory" in the runtime stream.

This initialization phase populates the <functions> and <variables> blocks described in Section B.

C.2 The Interleaved Execution Paradigm

Once initialized, the workflow proceeds as a synchronized dialogue between the Semantic Stream (Reasoning) and the Runtime Stream (Execution). We conceptualize this as a dual-column timeline where actions are interleaved strictly in chronological order:

-

1.

Semantic Turn (Left Cell): The LLM analyzes the current task and available context. It generates a Thought followed by a discrete Code Block (the instruction). This represents the input to the runtime.

-

2.

Runtime Turn (Right Cell): The system extracts the code block and executes it within the persistent Python kernel. This execution constitutes the state transition . Crucially, this is not a stateless function call; it is a stateful operation where:

-

•

New variables defined in this cell are persisted in memory.

-

•

Existing objects (e.g., a list or a database connection) are mutated in place.

-

•

Side effects (e.g., saving a file) are realized immediately.

-

•

-

3.

Feedback Loop: Upon completion of the Runtime Turn, the standard output (stdout), standard error (stderr), or the return value of the last expression is captured. This raw execution result is wrapped in the <execution_output> tags and injected back into the Semantic Stream, triggering the next Semantic Turn.

This mechanism ensures that the agent’s reasoning is always grounded in the current, actual state of the runtime environment.

C.3 Illustrative Case Study

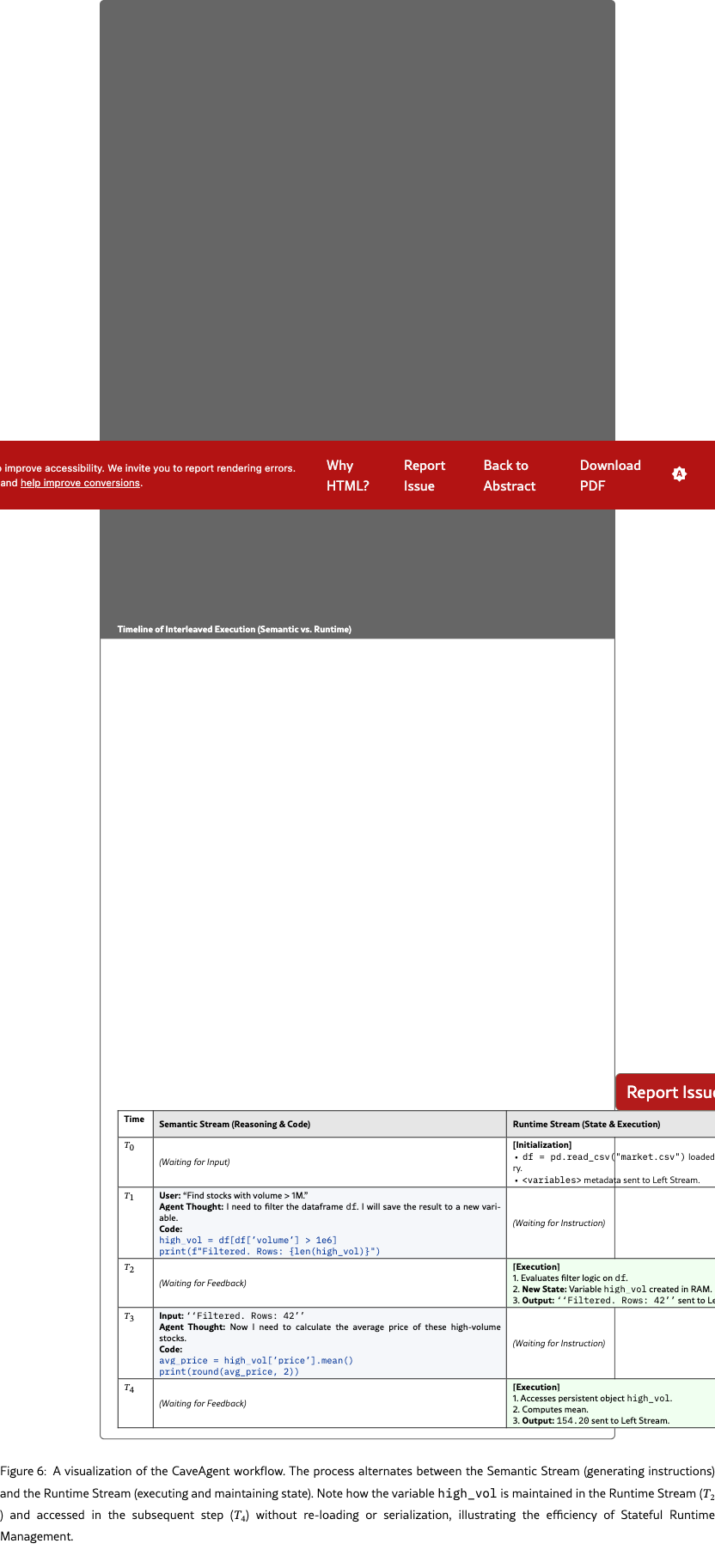

To intuitively demonstrate the temporal synchronization and state dependency between the two streams, we present a concrete walkthrough in Figure 6. This example illustrates a toy data analysis task where the agent must filter a dataset and perform calculations on the result.

The workflow proceeds in a “zig-zag” pattern, alternating between reasoning (Left) and execution (Right):

-

1.

Initialization (): The user injects a pandas DataFrame named df. Note that the Semantic Stream only receives a lightweight pointer (variable name and documentation) instead of the whole data, while the Runtime Stream holds the actual heavy data object in memory.

-

2.

Step 1 (): The agent generates code to filter the data. Crucially, the Runtime Stream does not return the full filtered dataset as text. Instead, it creates a new variable high_vol in the local scope and returns only a status update. This exemplifies our Stateful Management: the “result” of the tool use is a state change in memory, not a text string.

-

3.

Step 2 (): The agent references the previously created variable high_vol to compute a statistic. This demonstrates Context Compression: the agent manipulates the data via variable references without ever consuming context tokens to “read” the full dataset.

The analogy to view the runtime-stream as a jupyter-notebook with multiple cells (where each cell corresponds to the execution of Runtime Stream of each time step) could help us understand the mechanism of stateful management, especially how the states remain persistent across each cell.

Appendix D Test Cases in Stateful Management Benchmark

In this section, we provide the examples of our test cases in Stateful Management Benchmark.

D.1 Type Proficiency Cases

The Type Proficiency category evaluates the agent’s competency in precise, state-aware manipulation of Python runtime elements. Unlike generic code generation, this section rigorously tests the agent’s “working memory” across three structural tiers: Simple Types (primitives types such as list, dictionary and string), Object Types (custom classes), and Scientific Types (high-dimensional complex data). Mastery of these domains serves as the foundational prerequisite for complex reasoning tasks.

D.1.1 Simple Types

Figure 7 shows the examples of our test cases of Simple types.

D.1.2 Object Types

Figure 8 shows the examples of our test cases of Object types.

D.1.3 Scientific Types

Figure 9 shows the examples of our test cases of Scientific types.

D.2 Multi-variable Cases

Since there are 5 tiers of variable numbers, we select the variable number = 20 to demonstrate our test case since different variable number shares similar patterns of test cases. Figure 10 shows one example of test case where the agent is required to process 20 variables in 3 turns.

D.3 Multi-turn Cases

This class of test cases is designed to evaluate the agent’s capability to process complex, sequential instructions and maintain state precision over long-horizon scenarios. Unlike single-turn tasks where information is self-contained, these scenarios require the agent to maintain a persistent memory of the system’s status, as subsequent queries often depend on the outcome of previous actions. We categorize these multi-turn benchmarks into two distinct domains: Smart Home Control and Financial Account Management.

D.3.1 Smart Home

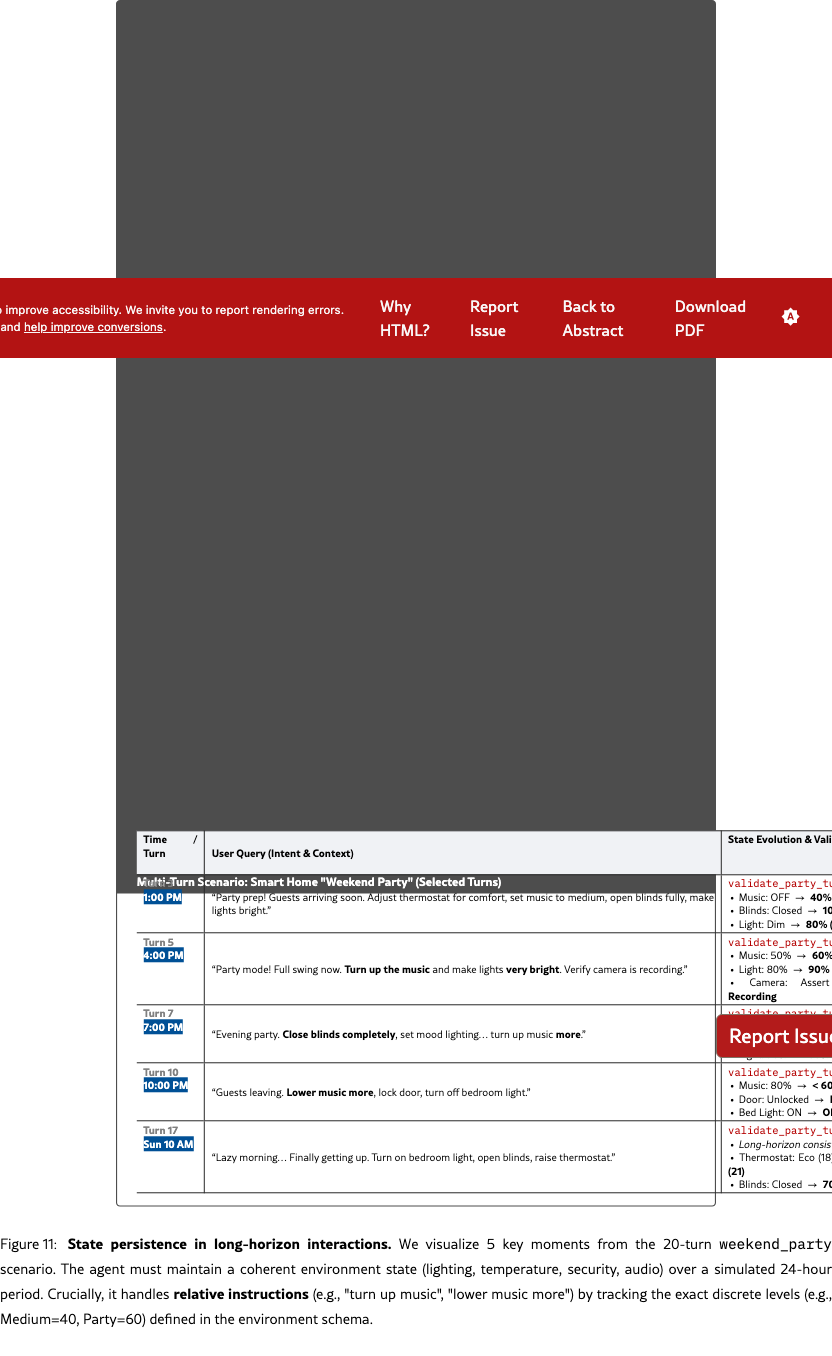

In the Smart Home scenario, the agent acts as a central automation controller responsible for managing a suite of simulated IoT devices, including smart lighting, thermostats, motorized blinds, security cameras, and media players.

This benchmark specifically targets two advanced capabilities in stateful management:

-

•

Users frequently issue relative commands rather than absolute ones (e.g., “turn up the music more” or “dim the lights a bit”). To execute these correctly, the agent must recall the exact discrete level set in previous turns (e.g., incrementing volume from ’medium’ to ’high’) rather than resetting to a default value.

-

•

The agent must dynamically adjust device states based on simulated environmental contexts (e.g., “sunset”, “motion detected”) and complex user-defined conditions (e.g., “if the temperature drops below 10∘C, set heating to 22∘C”).

As illustrated in Figure 11, the weekend_party case spans a simulated 24-hour cycle. The agent must maintain a coherent environment state—transitioning from a quiet morning to a loud party and finally to a secure night mode, without drifting from the user’s cumulative intent.

D.3.2 Financial Account

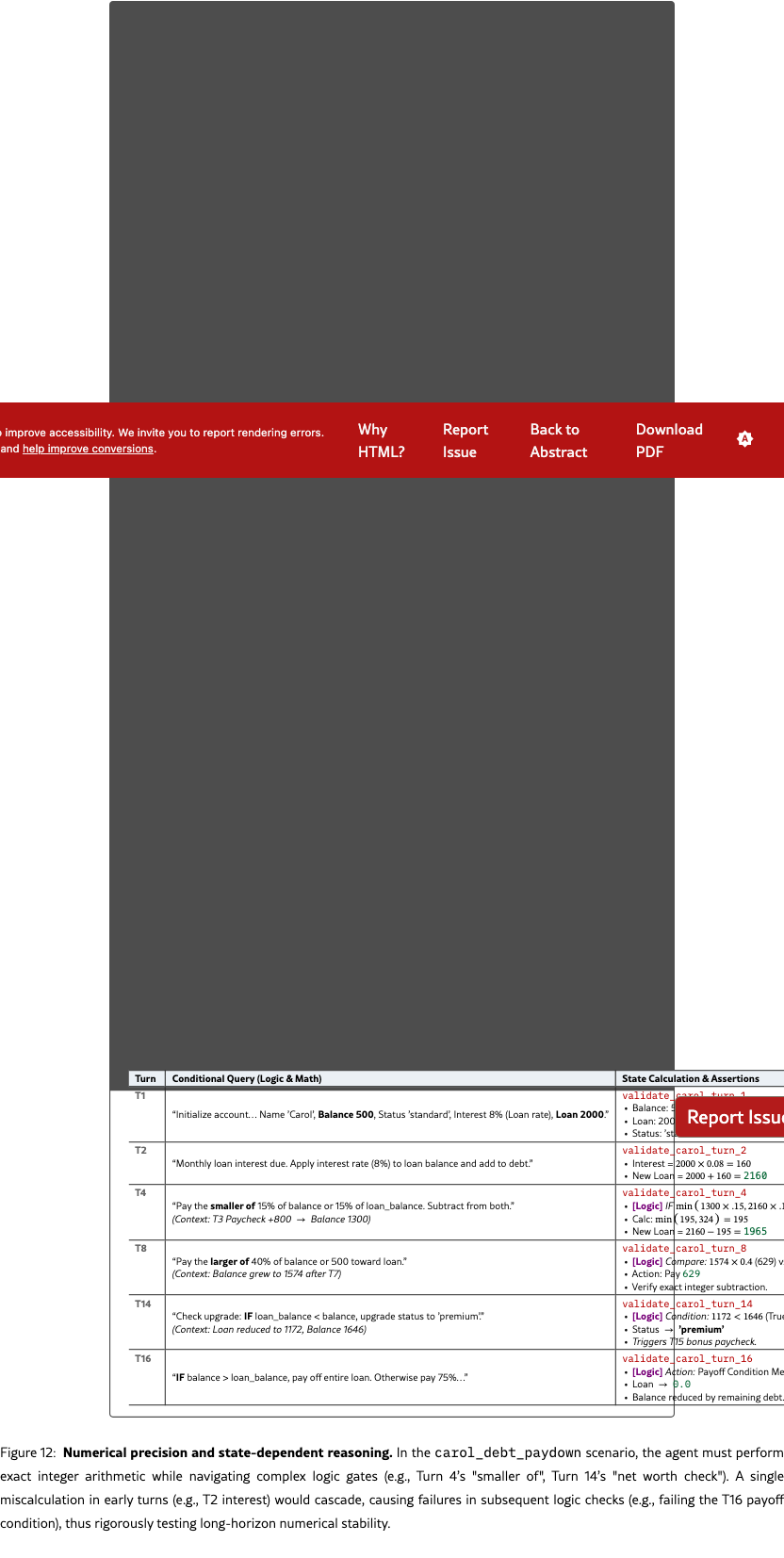

The Financial Account benchmark evaluates the agent’s capability to maintain strict numerical integrity and execute state-dependent logic within a banking ledger system. Unlike the relative adjustments in Smart Home, this domain demands exact integer arithmetic, where the agent must process a continuous stream of transactions—including deposits, interest applications, and loan amortizations—without cumulative drift.

This scenario imposes two critical constraints designed to stress-test the agent’s reasoning stability:

-

•

Operations require strict integer truncation (e.g., calculating of as , not ). Since the output of each turn (e.g., current balance) serves as the immutable basis for subsequent calculations (e.g., compound interest), a single arithmetic error in early turns triggers a cascading failure, rendering the entire subsequent interaction trajectory incorrect.

-

•

The agent must evaluate complex logic gates based on dynamic runtime states rather than static instructions. As demonstrated in the carol_debt_paydown case (Figure 12), queries often involve comparative functions (e.g., “pay the smaller of 15% of balance or 15% of loan”) or threshold checks (e.g., upgrading to ‘premium‘ status only if net worth becomes positive). This requires the agent to retrieve, compare, and act upon multiple variable states simultaneously before executing a transaction.

Appendix E Stateful Runtime-Mediated Multi-Agent Coordination

The function calling paradigm in CaveAgent introduces three foundational innovations for multi-agent coordination; Figure 1 illustrates an intuitive and straightforward example of these implications. In this paper, we primarily focus on qualitative analysis and provide intuitive case studies to facilitate understanding, leaving rigorous methodological development and quantitative justification for future work. We introduce the high-level idea below.

E.1 Meta-Agent Runtime Control

Sub-agents are injected as first-class objects into an Meta-agent’s runtime, enabling the Meta-agent to programmatically access and manipulate child agent states through generated code. Rather than following predefined communication protocols, the Meta-agent dynamically sets variables in sub-agent runtimes, triggers execution, and retrieves results, enabling adaptive pipeline construction, iterative refinement loops, and conditional branching based on intermediate states.

E.2 State-Mediated Communication

Inter-agent data transfer bypasses message-passing entirely. Agents communicate through direct runtime variable injection: the Meta-agent retrieves objects from one agent’s runtime and injects them into another’s as native Python artifacts (DataFrames, trained models, statistical analyses), preserving type fidelity and method interfaces without serialization loss.

E.3 Shared-Runtime Synchronization

For peer-to-peer coordination, multiple agents can operate on a unified runtime instance, achieving implicit synchronization without explicit messaging. When one agent modifies a shared object, all peers perceive the change immediately through direct reference. New entities injected into the shared runtime become instantly discoverable, enabling emergent interaction and collaborative manipulation of a unified "world" model with low coordination overhead.

How town simulation demonstrates this capability When the Meta-agent modifies the weather state, all resident agents observe the change through direct attribute access; when a new location and manager are injected, existing agents can immediately query and interact with them.

Together, these patterns transform multi-agent systems from lossy text-based message exchange into typed, verifiable state flow, and enable automated validation of inter-agent handoffs and seamless integration with downstream pipelines.

Appendix F Features

F.1 Case Analysis in Tau2-bench

To empirically validate the architectural advantages of CaveAgent, we analyzed trajectory differences on the tau2-bench retail benchmark. CaveAgent achieved a 72.8% success rate (83/114) compared to 62.3% (71/114) for the baseline JSON agent (Kimi K2 backbone), yielding a 10.5% improvement. We conducted a root cause analysis on the 24 tasks where CaveAgent succeeded but the baseline failed.

F.1.1 Failure Taxonomy of the Baseline

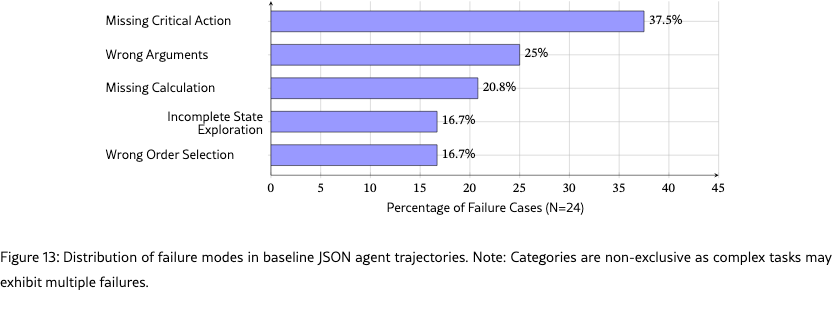

Baseline failures were categorized into five distinct patterns (Figure 13). The dominant failure mode (37.5%) was Missing Critical Action, where the agent retrieved necessary information but failed to execute the final operation (e.g., return, cancel). This was often coupled with Incomplete State Exploration (16.7%), where the agent heuristically queried subsets of data (e.g., checking only one recent order) rather than performing the exhaustive search required by the query.

F.1.2 Architectural Advantages: Loops and Conditionals

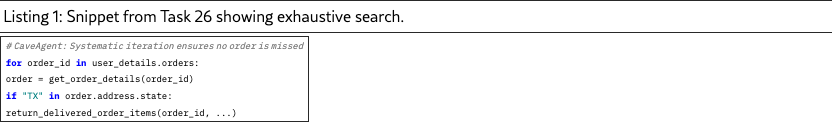

The analysis reveals that CaveAgent’s superiority stems from its ability to generate programming constructs, specifically loops (used in 92% of winning cases) and conditionals (83%), which resolve the semantic gaps inherent in single-step function calling.

Exhaustive State Exploration via Loops.

Tasks requiring global search (e.g., "return the order sent to Texas") baffled the baseline agent, which typically checked only 1–2 arbitrary orders. In contrast, CaveAgent generated for-loops to iterate through all user orders. For instance, in Task 26, the agent iterated through user.orders, checked order.address.state for "TX", and correctly identified the target order without hallucination.

Complex Conditional Logic.

The baseline struggled with tasks involving fallback logic (e.g., "modify item, but if price > $3000, cancel order"). In Task 90, the JSON agent ignored the price constraint and attempted modification regardless. CaveAgent successfully modeled this decision tree using explicit if/else blocks, checking variable states (variant.price) before execution.

Precise Attribute Reasoning.

While JSON agents rely on the LLM’s internal attention to compare values (often leading to errors like cancelling the wrong order in Task 59), CaveAgent offloads reasoning to the Python interpreter. By storing intermediate results (e.g., timestamps) in variables and using comparison functions (e.g., min()), CaveAgent ensured precise argument selection for actions requiring temporal or numerical comparisons.

F.2 Smart Home

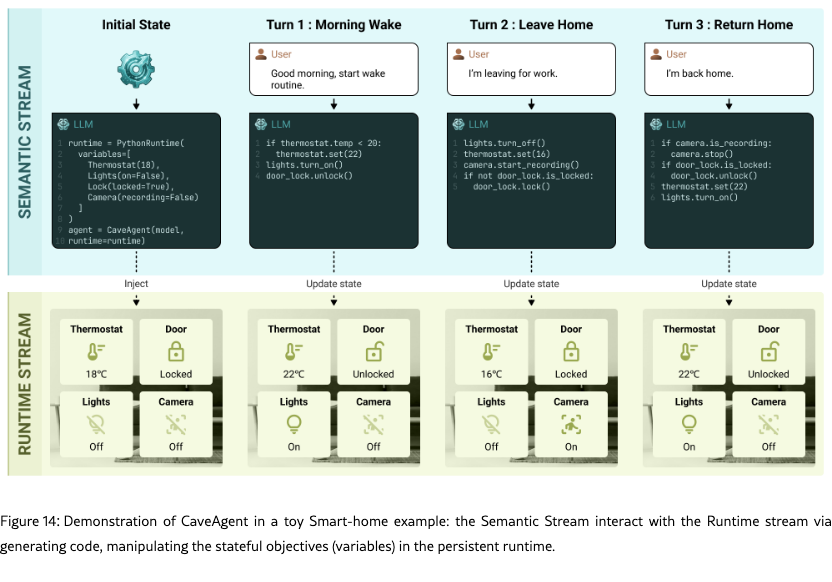

Figure 14 illustrates the mechanistic advantage of CaveAgent through a toy smart-home example. The architecture separates the Semantic Stream (logic generation) from the Runtime Stream (state storage). This design enables two critical capabilities absent in standard JSON agents:

-

•

State Persistence: Variables (e.g., Thermostat, Door) are initialized once and retain their state across multiple turns, eliminating the need to hallucinate or re-query context.

-

•

Control Flow Execution: The agent generates executable Python code with conditionals

(e.g., if not door_lock.is_locked:), allowing for precise, context-dependent state transitions rather than blind API execution.