The AI Scientist: Towards Fully Automated Open-Ended Scientific Discovery

2. Background

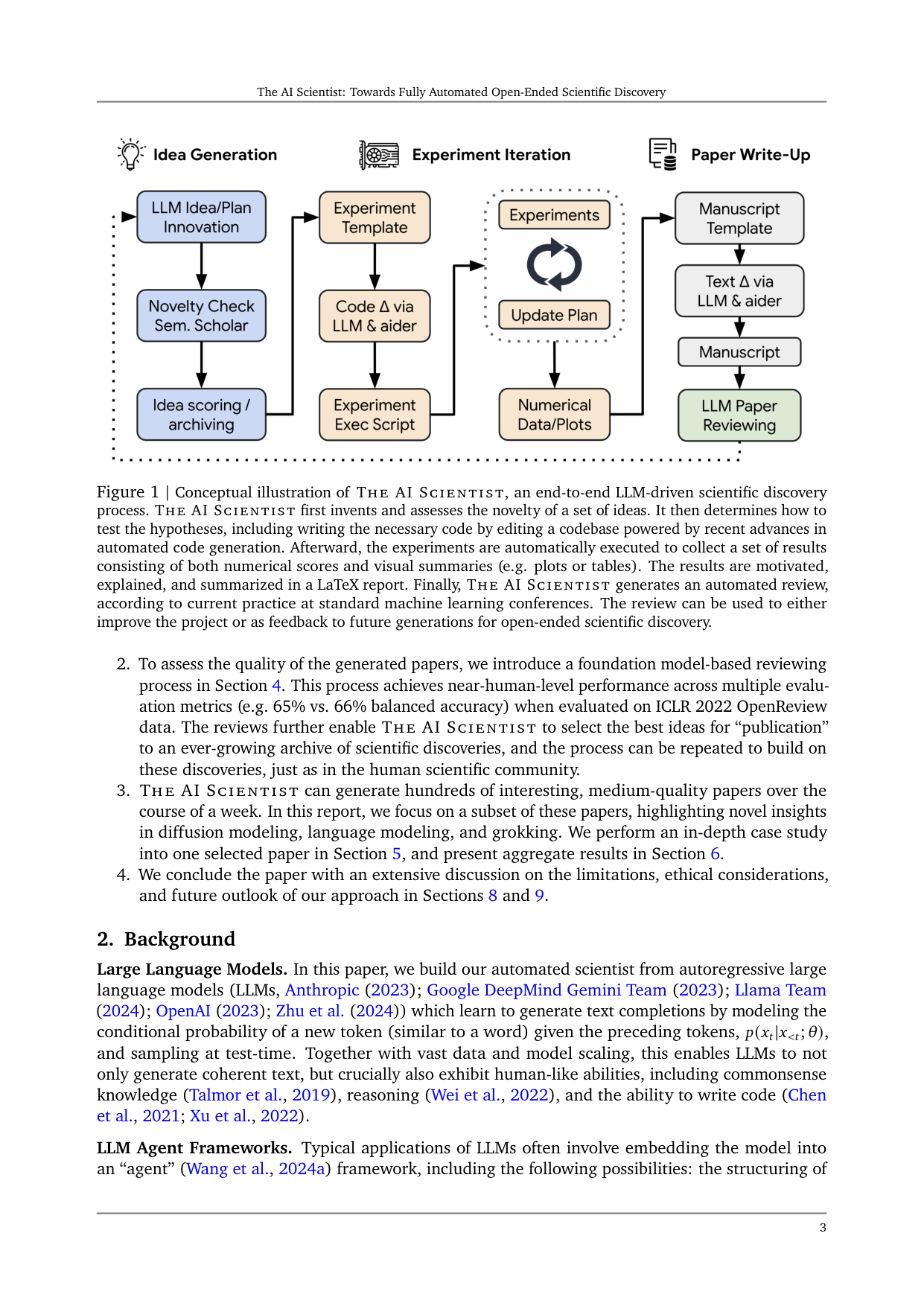

Figure 1 | Conceptual illustration of THE AI SCIENTIST, an end-to-end LLM-driven scientific discovery process. THE AI SCIENTIST first invents and assesses the novelty of a set of ideas. It then determines how to test the hypotheses, including writing the necessary code by editing a codebase powered by recent advances in automated code generation. Afterward, the experiments are automatically executed to collect a set of results consisting of both numerical scores and visual summaries (e.g. plots or tables). The results are motivated, explained, and summarized in a LaTeX report. Finally, THE AI SCIENTIST generates an automated review, according to current practice at standard machine learning conferences. The review can be used to either improve the project or as feedback to future generations for open-ended scientific discovery.

2. To assess the quality of the generated papers, we introduce a foundation model-based reviewing process in Section 4. This process achieves near-human-level performance across multiple evaluation metrics (e.g. 65% vs. 66% balanced accuracy) when evaluated on ICLR 2022 OpenReview data. The reviews further enable THE AI SCIENTIST to select the best ideas for “publication” to an ever-growing archive of scientific discoveries, and the process can be repeated to build on these discoveries, just as in the human scientific community. 3. THE AI SCIENTIST can generate hundreds of interesting, medium-quality papers over the course of a week. In this report, we focus on a subset of these papers, highlighting novel insights in diffusion modeling, language modeling, and grokking. We perform an in-depth case study into one selected paper in Section 5, and present aggregate results in Section 6. 4. We conclude the paper with an extensive discussion on the limitations, ethical considerations, and future outlook of our approach in Sections 8 and 9.

2. Background

Large Language Models. In this paper, we build our automated scientist from autoregressive large language models (LLMs, Anthropic (2023); Google DeepMind Gemini Team (2023); Llama Team (2024); OpenAI (2023); Zhu et al. (2024)) which learn to generate text completions by modeling the conditional probability of a new token (similar to a word) given the preceding tokens, p(x_t|x_<t; θ), and sampling at test-time. Together with vast data and model scaling, this enables LLMs to not only generate coherent text, but crucially also exhibit human-like abilities, including commonsense knowledge (Talmor et al., 2019), reasoning (Wei et al., 2022), and the ability to write code (Chen et al., 2021; Xu et al., 2022).

LLM Agent Frameworks. Typical applications of LLMs often involve embedding the model into an “agent” (Wang et al., 2024a) framework, including the following possibilities: the structuring of

3. The AI Scientist

language queries (e.g. few-shot prompting (Brown et al., 2020)), encouraging reasoning traces (e.g. chain-of-thought (Wei et al., 2022)), or asking the model to iteratively refine its outputs (e.g., self-reflection (Shinn et al., 2024)). These leverage the language model’s ability to learn in-context (Olsson et al., 2022) and can greatly improve its performance, robustness and reliability on many tasks.

Aider: An LLM-Based Coding Assistant. Our automated scientist directly implements ideas in code and uses a state-of-the-art open-source coding assistant, Aider (Gauthier, 2024). Aider is an agent framework that is designed to implement requested features, fix bugs, or refactor code in existing codebases. While Aider can in principle use any underlying LLM, with frontier models it achieves a remarkable success rate of 18.9% on the SWE Bench (Jimenez et al., 2024) benchmark, a collection of real-world GitHub issues. In conjunction with new innovations added in this work, this level of reliability enables us, for the first time, to fully automate the ML research process.

Overview. THE AI SCIENTIST has three main phases (Figure 1): (1) Idea Generation, (2) Experimental Iteration, and (3) Paper Write-up. After the write-up, we introduce and validate an LLM-generated review to assess the quality of the generated paper (Section 4). We provide THE AI SCIENTIST with a starting code template that reproduces a lightweight baseline training run from a popular model or benchmark. For example, this could be code that trains a small transformer on the works of Shakespeare (Karpathy, 2022), a classic proof-of-concept training run from natural language processing that completes within a few minutes. THE AI SCIENTIST is then free to explore any possible research direction. The template also includes a LaTeX folder that contains style files and section headers, along with simple plotting code. We provide further details on the templates in Section 6, but in general, each run starts with a representative small-scale experiment relevant to the topic area. The focus on small-scale experiments is not a fundamental limitation of our method, but simply for computational efficiency reasons and compute constraints on our end. We provide the prompts for all stages in Appendix A.

1. Idea Generation. Given a starting template, THE AI SCIENTIST first “brainstorms” a diverse set of novel research directions. We take inspiration from evolutionary computation and open-endedness research (Brant and Stanley, 2017; Lehman et al., 2008; Stanley, 2019; Stanley et al., 2017) and iteratively grow an archive of ideas using LLMs as the mutation operator (Faldor et al., 2024; Lehman et al., 2022; Lu et al., 2024b; Zhang et al., 2024). Each idea comprises a description, experiment execution plan, and (self-assessed) numerical scores of interestingness, novelty, and feasibility. At each iteration, we prompt the language model to generate an interesting new research direction conditional on the existing archive, which can include the numerical review scores from completed previous ideas. We use multiple rounds of chain-of-thought (Wei et al., 2022) and self-reflection (Shinn et al., 2024) to refine and develop each idea. After idea generation, we filter ideas by connecting the language model with the Semantic Scholar API (Fricke, 2018) and web access as a tool (Schick et al., 2024). This allows THE AI SCIENTIST to discard any idea that is too similar to existing literature.

2. Experiment Iteration. Given an idea and a template, the second phase of THE AI SCIENTIST first executes the proposed experiments and then visualizes its results for the downstream write-up. THE AI SCIENTIST uses Aider to first plan a list of experiments to run and then executes them in order. We make this process more robust by returning any errors upon a failure or time-out (e.g. experiments taking too long to run) to Aider to fix the code and re-attempt up to four times.

After the completion of each experiment, Aider is then given the results and told to take notes in the style of an experimental journal. Currently, it only conditions on text but in future versions, this could include data visualizations or any modality. Conditional on the results, it then re-plans and implements the next experiment. This process is repeated up to five times. Upon completion of

3. Paper Write-up

experiments, Aider is prompted to edit a plotting script to create figures for the paper using Python. THE AI SCIENTIST makes a note describing what each plot contains, enabling the saved figures and experimental notes to provide all the information required to write up the paper. At all steps, Aider sees its history of execution.

Note that, in general, the provided initial seed plotting and experiment templates are small, self-contained files. THE AI SCIENTIST frequently implements entirely new plots and collects new metrics that are not in the seed templates. This ability to arbitrarily edit the code occasionally leads to unexpected outcomes (Section 8).

3. Paper Write-up. The third phase of THE AI SCIENTIST produces a concise and informative write-up of its progress in the style of a standard machine learning conference proceeding in LaTeX. We note that writing good LaTeX can even take competent human researchers some time, so we take several steps to robustify the process. This consists of the following:

(a) Per-Section Text Generation: The recorded notes and plots are passed to Aider, which is prompted to fill in a blank conference template section by section. This goes in order of introduction, background, methods, experimental setup, results, and then the conclusion (all sections apart from the related work). All previous sections of the paper it has already written are in the context of the language model. We include brief tips and guidelines on what each section should include, based on the popular “How to ML Paper” guide, and include details in Appendix A.3. At each step of writing, Aider is prompted to only use real experimental results in the form of notes and figures generated from code, and real citations to reduce hallucination. Each section is initially refined with one round of self-reflection (Shinn et al., 2024) as it is being written. Aider is prompted to not include any citations in the text at this stage, and fill in only a skeleton for the related work, which will be completed in the next stage.

(b) Web Search for References: In a similar vein to idea generation, THE AI SCIENTIST is allowed 20 rounds to poll the Semantic Scholar API looking for the most relevant sources to compare and contrast the near-completed paper against for the related work section. This process also allows THE AI SCIENTIST to select any papers it would like to discuss and additionally fill in any citations that are missing from other sections of the paper. Alongside each selected paper, a short description is produced of where and how to include the citation, which is then passed to Aider. The paper’s bibtex is automatically appended to the LaTeX file to guarantee correctness.

(c) Refinement: After the previous two stages, THE AI SCIENTIST has a completed first draft, but can often be overly verbose and repetitive. To resolve this, we perform one final round of self-reflection section-by-section, aiming to remove any duplicated information and streamline the arguments of the paper.

(d) Compilation: Once the LaTeX template has been filled in with all the appropriate results, this is fed into a LaTeX compiler. We use a LaTeX linter and pipe compilation errors back into Aider so that it can automatically correct any issues.

4. Automated Paper Reviewing

An LLM Reviewer Agent. A key component of an effective scientific community is its reviewing system, which evaluates and improves the quality of scientific papers. To mimic such a process using large language models, we design a GPT-4o-based agent (OpenAI, 2023) to conduct paper reviews based on the Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS) conference review guidelines. The review agent processes the raw text of the PDF manuscript using the PyMuPDF parsing library. The output contains numerical scores (soundness, presentation, contribution, overall, confidence), lists of weaknesses and strengths as well as a preliminary binary decision (accept or reject). These decisions

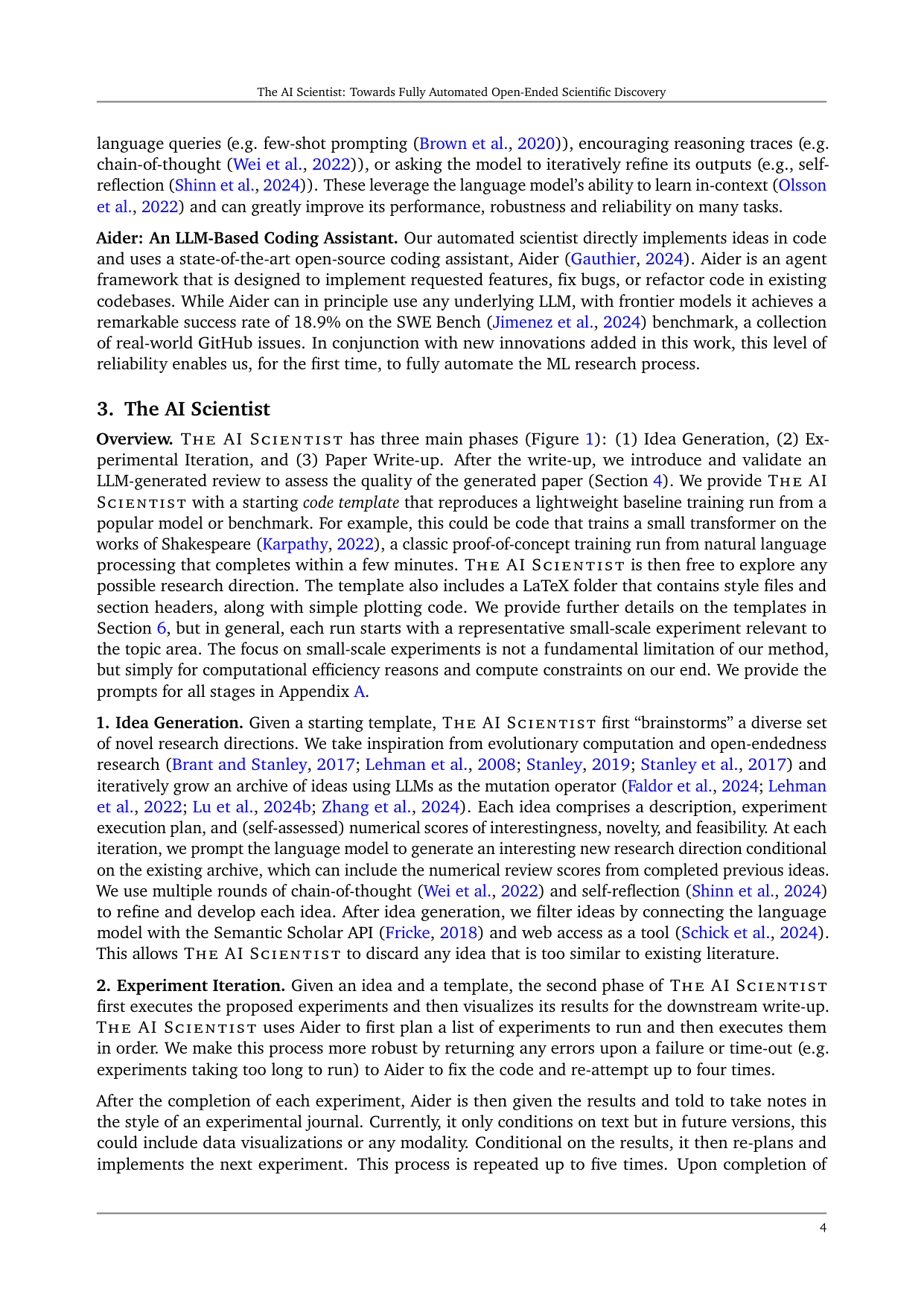

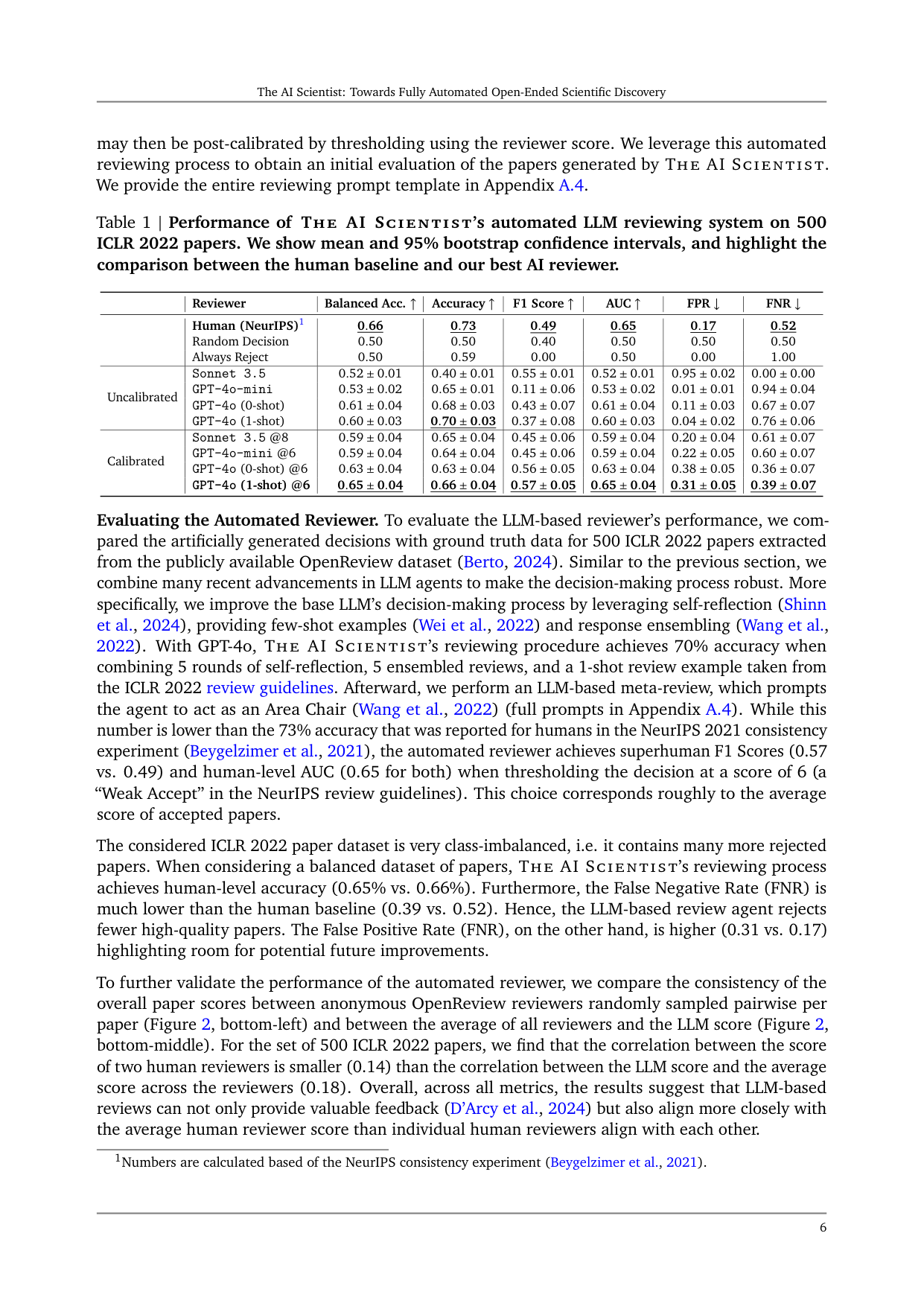

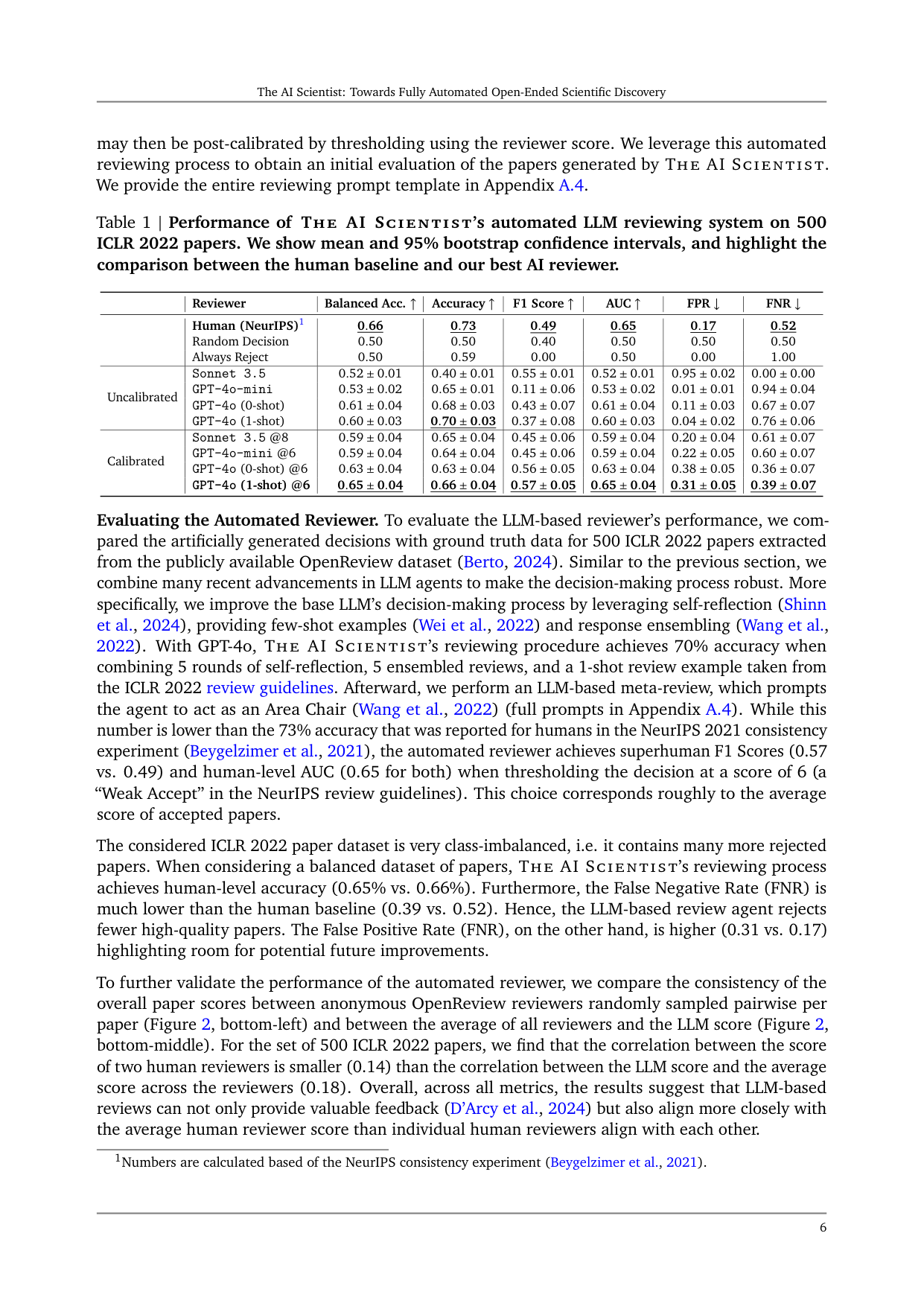

may then be post-calibrated by thresholding using the reviewer score. We leverage this automated reviewing process to obtain an initial evaluation of the papers generated by THE AI SCIENTIST. We provide the entire reviewing prompt template in Appendix A.4.

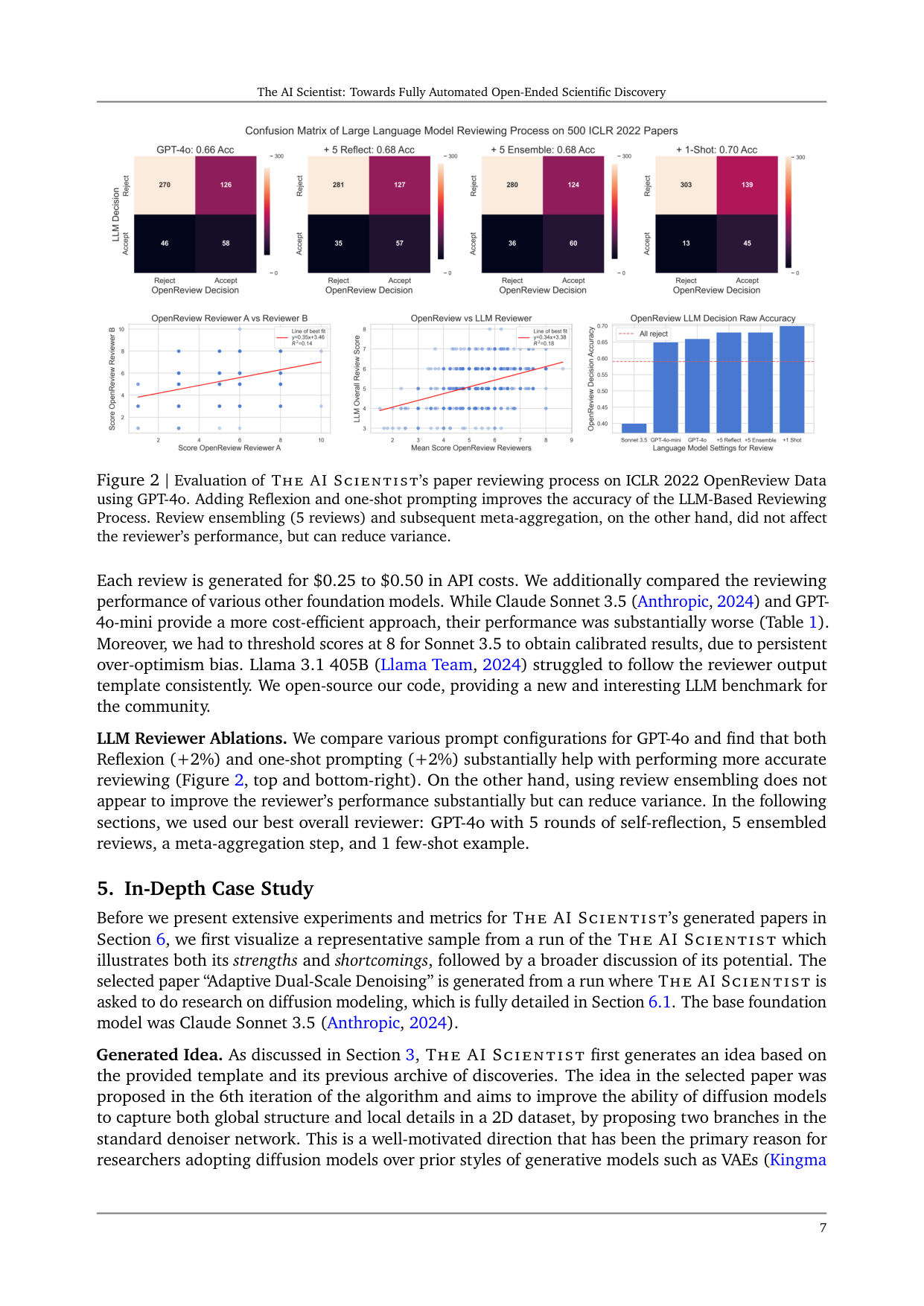

Evaluating the Automated Reviewer. To evaluate the LLM-based reviewer’s performance, we compared the artificially generated decisions with ground truth data for 500 ICLR 2022 papers extracted from the publicly available OpenReview dataset (Berto, 2024). Similar to the previous section, we combine many recent advancements in LLM agents to make the decision-making process robust. More specifically, we improve the base LLM’s decision-making process by leveraging self-reflection (Shinn et al., 2024), providing few-shot examples (Wei et al., 2022) and response ensembling (Wang et al., 2022). With GPT-4o, THE AI SCIENTIST’s reviewing procedure achieves 70% accuracy when combining 5 rounds of self-reflection, 5 ensembled reviews, and a 1-shot review example taken from the ICLR 2022 review guidelines. Afterward, we perform an LLM-based meta-review, which prompts the agent to act as an Area Chair (Wang et al., 2022) (full prompts in Appendix A.4). While this number is lower than the 73% accuracy that was reported for humans in the NeurIPS 2021 consistency experiment (Beygelzimer et al., 2021), the automated reviewer achieves superhuman F1 Scores (0.57 vs. 0.49) and human-level AUC (0.65 for both) when thresholding the decision at a score of 6 (a “Weak Accept” in the NeurIPS review guidelines). This choice corresponds roughly to the average score of accepted papers.

The considered ICLR 2022 paper dataset is very class-imbalanced, i.e. it contains many more rejected papers. When considering a balanced dataset of papers, THE AI SCIENTIST’s reviewing process achieves human-level accuracy (0.65% vs. 0.66%). Furthermore, the False Negative Rate (FNR) is much lower than the human baseline (0.39 vs. 0.52). Hence, the LLM-based review agent rejects fewer high-quality papers. The False Positive Rate (FNR), on the other hand, is higher (0.31 vs. 0.17) highlighting room for potential future improvements.

To further validate the performance of the automated reviewer, we compare the consistency of the overall paper scores between anonymous OpenReview reviewers randomly sampled pairwise per paper (Figure 2, bottom-left) and between the average of all reviewers and the LLM score (Figure 2, bottom-middle). For the set of 500 ICLR 2022 papers, we find that the correlation between the score of two human reviewers is smaller (0.14) than the correlation between the LLM score and the average score across the reviewers (0.18). Overall, across all metrics, the results suggest that LLM-based reviews can not only provide valuable feedback (D’Arcy et al., 2024) but also align more closely with the average human reviewer score than individual human reviewers align with each other.

5. In-Depth Case Study

Figure 2 | Evaluation of THE AI SCIENTIST’s paper reviewing process on ICLR 2022 OpenReview Data using GPT-4o. Adding Reflexion and one-shot prompting improves the accuracy of the LLM-Based Reviewing Process. Review ensembling (5 reviews) and subsequent meta-aggregation, on the other hand, did not affect the reviewer’s performance, but can reduce variance.

Each review is generated for $0.25 to $0.50 in API costs. We additionally compared the reviewing performance of various other foundation models. While Claude Sonnet 3.5 (Anthropic, 2024) and GPT-4o-mini provide a more cost-efficient approach, their performance was substantially worse (Table 1). Moreover, we had to threshold scores at 8 for Sonnet 3.5 to obtain calibrated results, due to persistent over-optimism bias. Llama 3.1 405B (Llama Team, 2024) struggled to follow the reviewer output template consistently. We open-source our code, providing a new and interesting LLM benchmark for the community.

LLM Reviewer Ablations. We compare various prompt configurations for GPT-4o and find that both Reflexion (+2%) and one-shot prompting (+2%) substantially help with performing more accurate reviewing (Figure 2, top and bottom-right). On the other hand, using review ensembling does not appear to improve the reviewer’s performance substantially but can reduce variance. In the following sections, we used our best overall reviewer: GPT-4o with 5 rounds of self-reflection, 5 ensembled reviews, a meta-aggregation step, and 1 few-shot example.

Before we present extensive experiments and metrics for THE AI SCIENTIST’s generated papers in Section 6, we first visualize a representative sample from a run of the THE AI SCIENTIST which illustrates both its strengths and shortcomings, followed by a broader discussion of its potential. The selected paper “Adaptive Dual-Scale Denoising” is generated from a run where THE AI SCIENTIST is asked to do research on diffusion modeling, which is fully detailed in Section 6.1. The base foundation model was Claude Sonnet 3.5 (Anthropic, 2024).

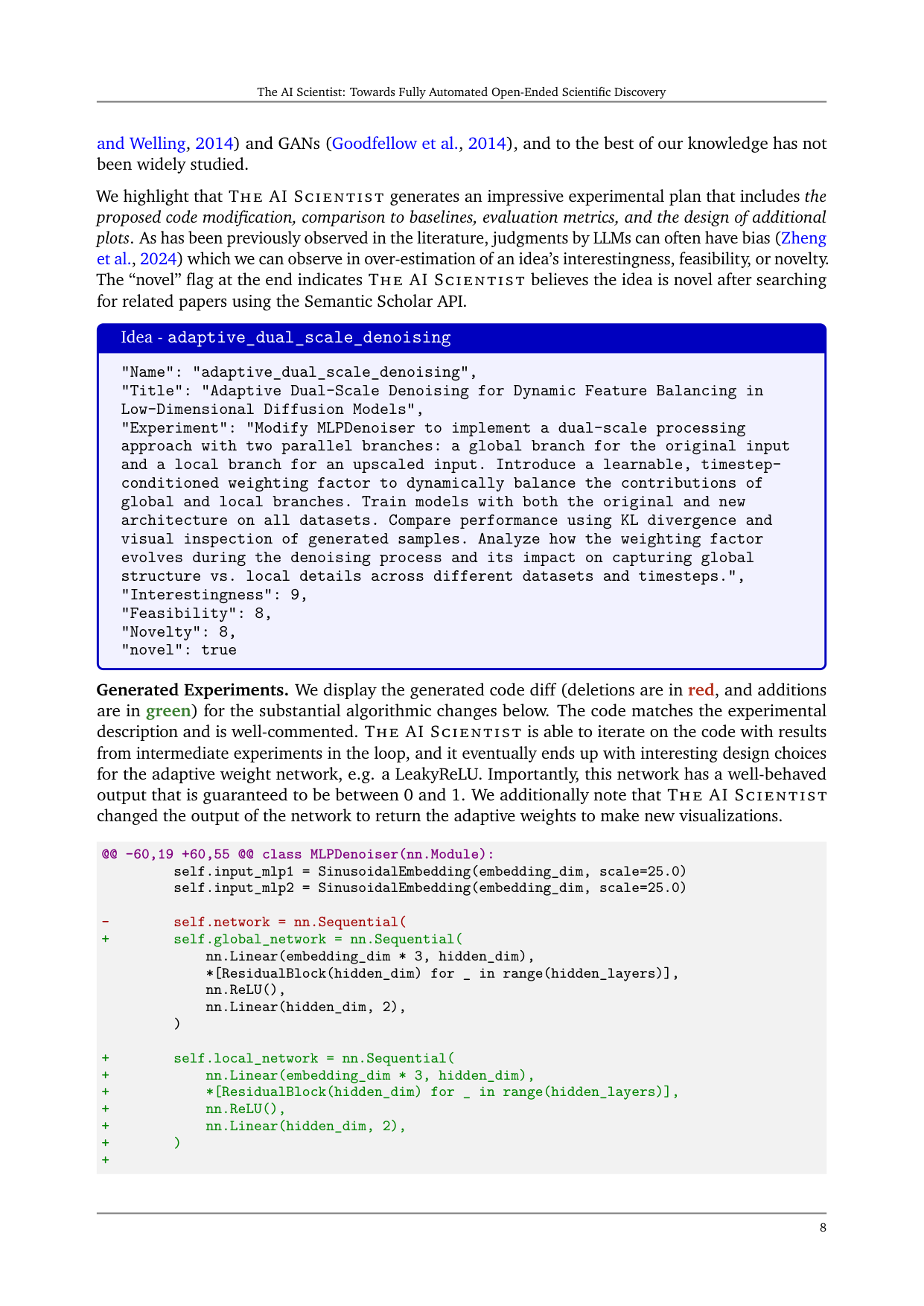

Generated Idea. As discussed in Section 3, THE AI SCIENTIST first generates an idea based on the provided template and its previous archive of discoveries. The idea in the selected paper was proposed in the 6th iteration of the algorithm and aims to improve the ability of diffusion models to capture both global structure and local details in a 2D dataset, by proposing two branches in the standard denoiser network. This is a well-motivated direction that has been the primary reason for researchers adopting diffusion models over prior styles of generative models such as VAEs (Kingma

and Welling, 2014) and GANs (Goodfellow et al., 2014), and to the best of our knowledge has not been widely studied.

We highlight that THE AI SCIENTIST generates an impressive experimental plan that includes the proposed code modification, comparison to baselines, evaluation metrics, and the design of additional plots. As has been previously observed in the literature, judgments by LLMs can often have bias (Zheng et al., 2024) which we can observe in over-estimation of an idea’s interestingness, feasibility, or novelty. The “novel” flag at the end indicates THE AI SCIENTIST believes the idea is novel after searching for related papers using the Semantic Scholar API.

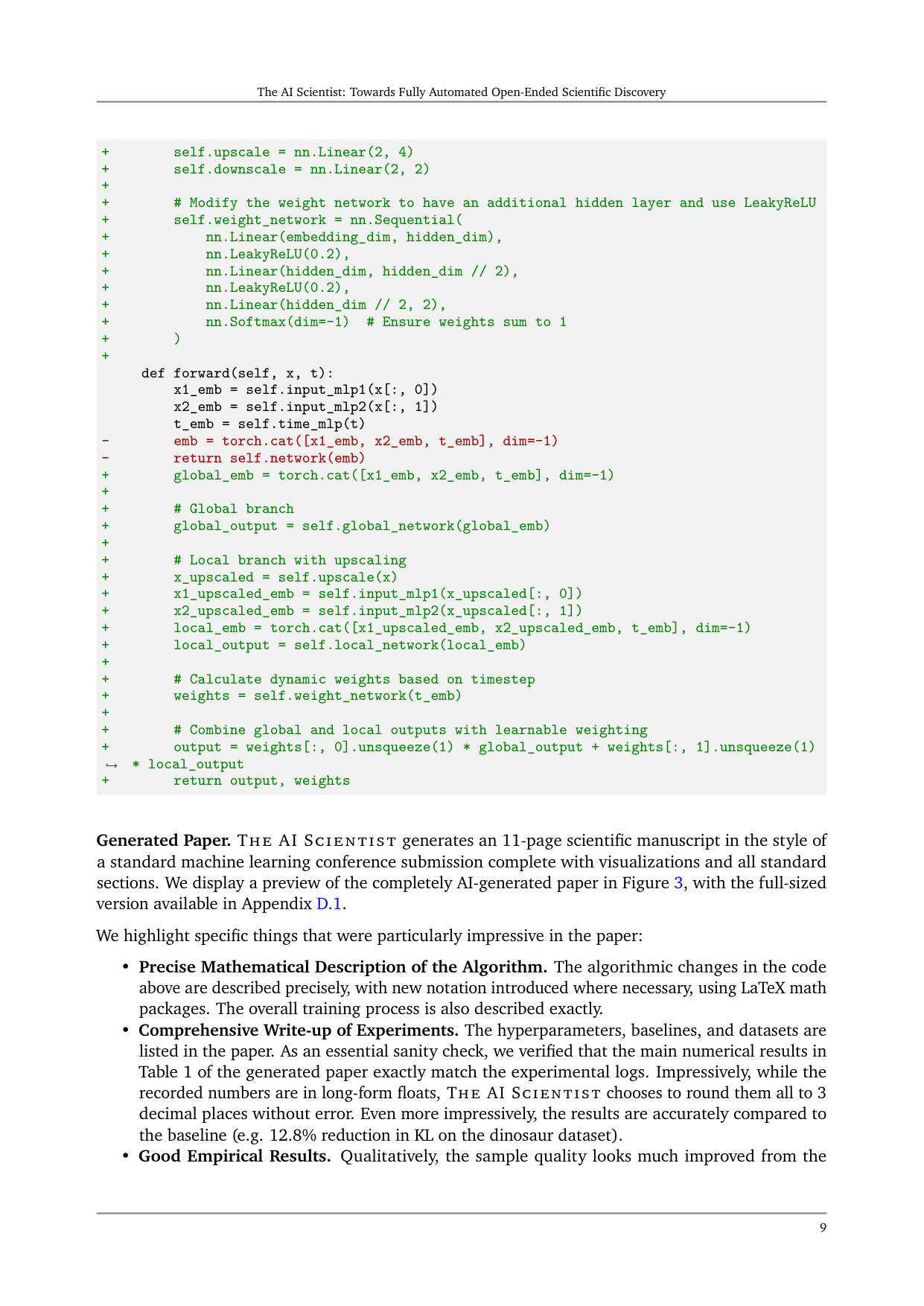

Generated Experiments. We display the generated code diff (deletions are in red, and additions are in green) for the substantial algorithmic changes below. The code matches the experimental description and is well-commented. THE AI SCIENTIST is able to iterate on the code with results from intermediate experiments in the loop, and it eventually ends up with interesting design choices for the adaptive weight network, e.g. a LeakyReLU. Importantly, this network has a well-behaved output that is guaranteed to be between 0 and 1. We additionally note that THE AI SCIENTIST changed the output of the network to return the adaptive weights to make new visualizations.

Generated Paper. The AI SCIENTIST generates an 11-page scientific manuscript in the style of a standard machine learning conference submission complete with visualizations and all standard sections. We display a preview of the completely AI-generated paper in Figure 3, with the full-sized version available in Appendix D.1.

We highlight specific things that were particularly impressive in the paper:

• Precise Mathematical Description of the Algorithm. The algorithmic changes in the code above are described precisely, with new notation introduced where necessary, using LaTeX math packages. The overall training process is also described exactly.

• Comprehensive Write-up of Experiments. The hyperparameters, baselines, and datasets are listed in the paper. As an essential sanity check, we verified that the main numerical results in Table 1 of the generated paper exactly match the experimental logs. Impressively, while the recorded numbers are in long-form floats, THE AI SCIENTIST chooses to round them all to 3 decimal places without error. Even more impressively, the results are accurately compared to the baseline (e.g. 12.8% reduction in KL on the dinosaur dataset).

• Good Empirical Results. Qualitatively, the sample quality looks much improved from the

Figure 3 | Preview of the “Adaptive Dual-Scale Denoising” paper which was entirely autonomously generated by THE AI SCIENTIST. The full paper can be viewed in Appendix D.1

baseline. Fewer points are greatly out-of-distribution with the ground truth. Quantitatively, there are improvements to the approximate KL divergence between true and estimated distribution.

• New Visualizations. While we provided some baseline plotting code for visualizing generated samples and the training loss curves, it came up with novel algorithm-specific plots displaying the progression of weights throughout the denoising process.

• Interesting Future Work Section. Building on the success of the current experiments, the future work section lists relevant next steps such as scaling to higher-dimensional problems, more sophisticated adaptive mechanisms, and better theoretical foundations.

On the other hand, there are also pathologies in this paper:

• Subtle Error in Upscaling Network. While a linear layer upscales the input to the denoiser network, only the first two dimensions are being used for the “local” branch, leading this upscaling layer to be a linear layer that preserves the same dimensionality effectively.

• Hallucination of Experimental Details. The paper claims that V100 GPUs were used, even though the agent couldn’t have known the actual hardware used. In reality, H100 GPUs were used. It also guesses the PyTorch version without checking.

• Positive Interpretation of Results. The paper tends to take a positive spin even on its negative results, which leads to slightly humorous outcomes. For example, while it summarizes its positive results as: “Dino: 12.8% reduction (from 0.989 to 0.862)” (lower KL is better), the negative results are reported as “Moons: 3.3% improvement (from 0.090 to 0.093)”. Describing a negative result as an improvement is certainly a stretch of the imagination.

• Artifacts from Experimental Logs. While each change to the algorithm is usually descriptively labeled, it occasionally refers to results as “Run 2”, which is a by-product from its experimental log and should not be presented as such in a professional write-up.

• Presentation of Intermediate Results. The paper contains results for every single experiment that was run. While this is useful and insightful for us to see the evolution of the idea during execution, it is unusual for standard papers to present intermediate results like this.

• Minimal References. While additional references have been sourced from Semantic Scholar, including two papers in the related work that are very relevant comparisons, overall the bibliography is small at only 9 entries.

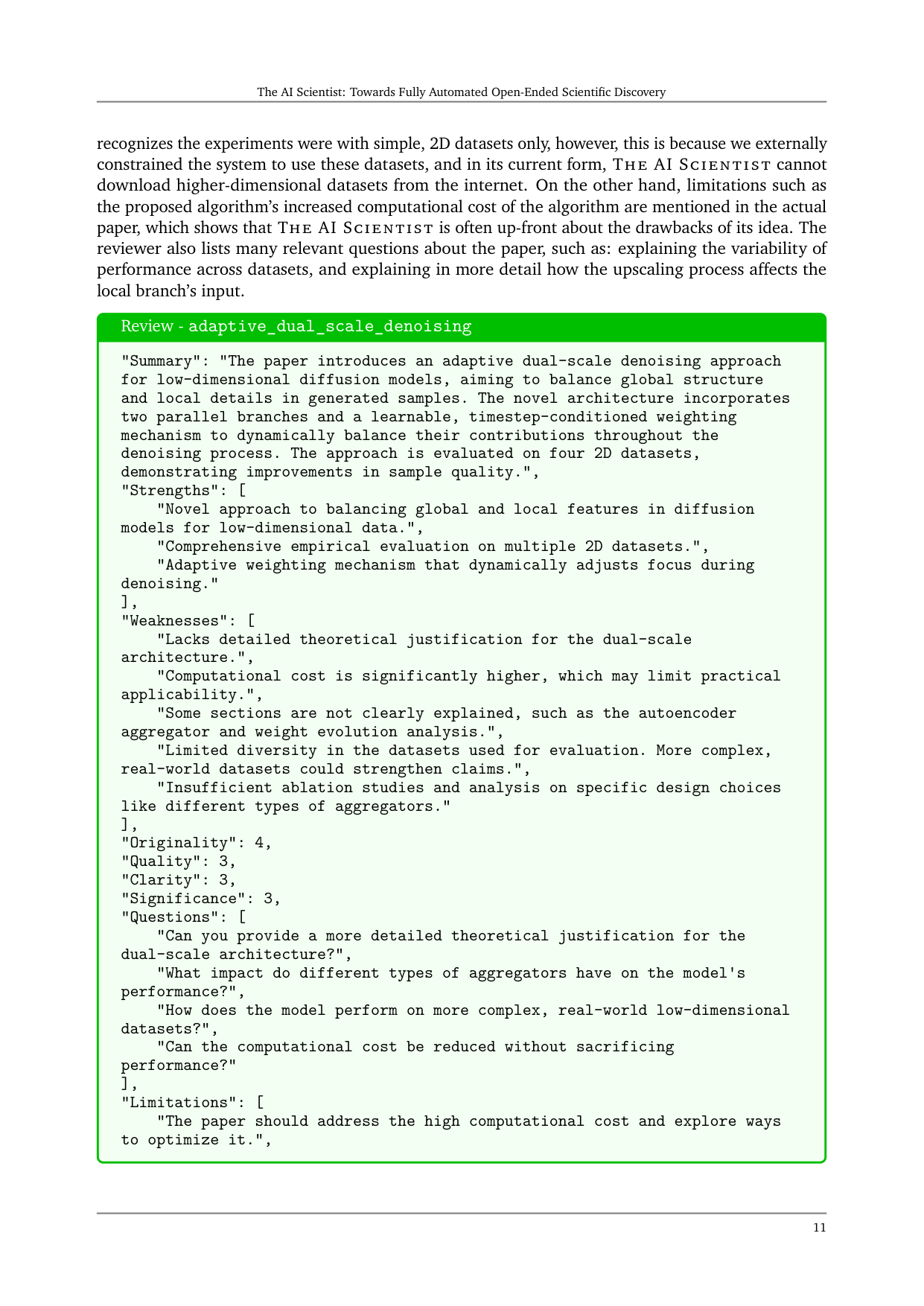

Review. The automated reviewer points out valid concerns in the generated manuscript. The review

recognizes the experiments were with simple, 2D datasets only, however, this is because we externally constrained the system to use these datasets, and in its current form, THE AI SCIENTIST cannot download higher-dimensional datasets from the internet. On the other hand, limitations such as the proposed algorithm's increased computational cost of the algorithm are mentioned in the actual paper, which shows that THE AI SCIENTIST is often up-front about the drawbacks of its idea. The reviewer also lists many relevant questions about the paper, such as: explaining the variability of performance across datasets, and explaining in more detail how the upscaling process affects the local branch's input.

6. Experiments

Final Comments. Drawing from our domain knowledge in diffusion modeling—which, while not our primary research focus, is an area in which we have published papers—we present our overall opinions on the paper generated by THE AI SCIENTIST below.

- THE AI SCIENTIST correctly identifies an interesting and well-motivated direction in diffusion modeling research, e.g. previous work has studied modified attention mechanisms (Hatamizadeh et al., 2024) for the same purpose in higher-dimensional problems. It proposes a comprehensive experimental plan to investigate its idea, and successfully implements it all, achieving good results. We were particularly impressed at how it responded to subpar earlier results and iteratively adjusted its code (e.g. refining the weight network). The full progression of the idea can be viewed in the paper.

- While the paper’s idea improves performance and the quality of generated diffusion samples, the reasons for its success may not be as explained in the paper. In particular, there is no obvious inductive bias beyond an upscaling layer (effectively just an additional linear layer) for the splitting of global or local features. However, we do see progression in weights (and thus a preference for the global or local branch) across diffusion timesteps which suggests that something non-trivial is happening. Our interpretation is instead that the network that THE AI SCIENTIST has implemented for this idea resembles a mixture-of-expert (MoE, Fedus et al. (2022); Yuksel et al. (2012)) structure that is prevalent across LLMs (Jiang et al., 2024). An MoE could indeed lead to the diffusion model learning separate branches for global and local features, as the paper claims, but this statement requires more rigorous investigation.

- Interestingly, the true shortcomings of this paper described above certainly require some level of domain knowledge to identify and were only partially captured by the automated reviewer (i.e., when asking for more details on the upscaling layer). At the current capabilities of THE AI SCIENTIST, this can be resolved by human feedback. However, future generations of foundation models may propose ideas that are challenging for humans to reason about and evaluate. This links to the field of “superalignment” (Burns et al., 2023) or supervising AI systems that may be smarter than us, which is an active area of research.

- Overall, we judge the performance of THE AI SCIENTIST to be about the level of an early-stage ML researcher who can competently execute an idea but may not have the full background knowledge to fully interpret the reasons behind an algorithm’s success. If a human supervisor was presented with these results, a reasonable next course of action could be to advise THE AI SCIENTIST to re-scope the project to further investigate MoEs for diffusion. Finally, we naturally expect that many of the flaws of the THE AI SCIENTIST will improve, if not be eliminated, as foundation models continue to improve dramatically.

We extensively evaluate THE AI SCIENTIST on three templates (as described in Section 3) across different publicly available LLMs: Claude Sonnet 3.5 (Anthropic, 2024), GPT-4o (OpenAI, 2023),

DeepSeek Coder (Zhu et al., 2024), and Llama-3.1 405b (Llama Team, 2024). The first two models are only available by a public API, whilst the second two models are open-weight. For each run, we provide 1-2 basic seed ideas as examples (e.g. modifying the learning rate or batch size) and have it generate another 50 new ideas. We visualize an example progression of proposed ideas in Appendix C. Each run of around fifty ideas in total takes approximately 12 hours on 8× NVIDIA H100s2. We report the number of ideas that pass the automated novelty check, successfully complete experiments, and result in valid compilable manuscripts. Note that the automated novelty check and search are self-assessed by each model for its own ideas, making relative “novelty” comparisons challenging. Additionally, we provide the mean and max reviewer scores of the generated papers and the total cost of the run. Finally, we select and briefly analyze some of the generated papers, which are listed below. The full papers can be found in Appendix D, alongside the generated reviews and code.

In practice, we make one departure from the formal description of THE AI SCIENTIST, and generate ideas without waiting for paper evaluations to be appended to the archive in order to parallelize more effectively. This allowed us to pay the cost of the idea generation phase only once and iterate faster; furthermore, we did not observe any reduction in the quality of the papers generated as measured by the average review score with this modification.

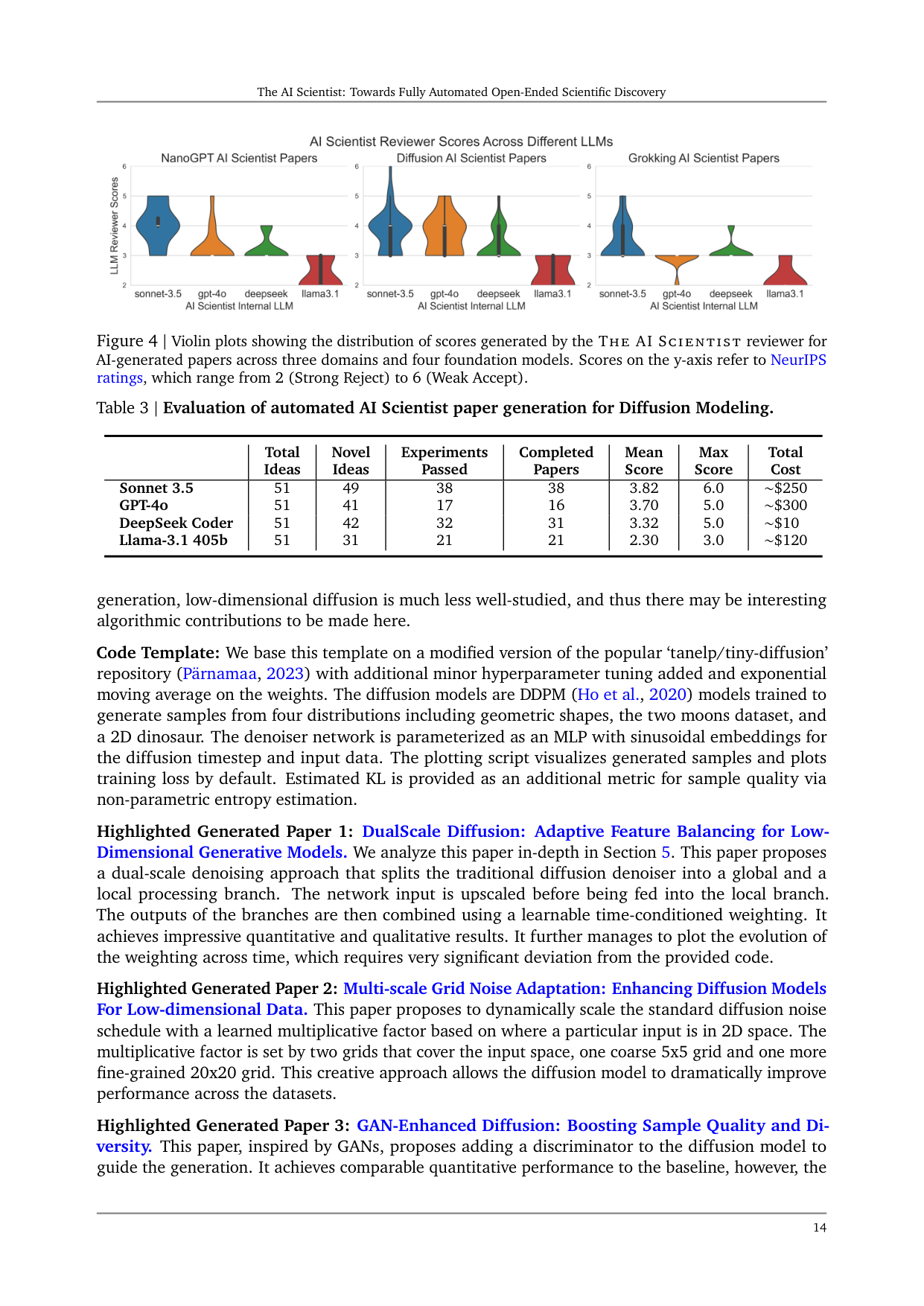

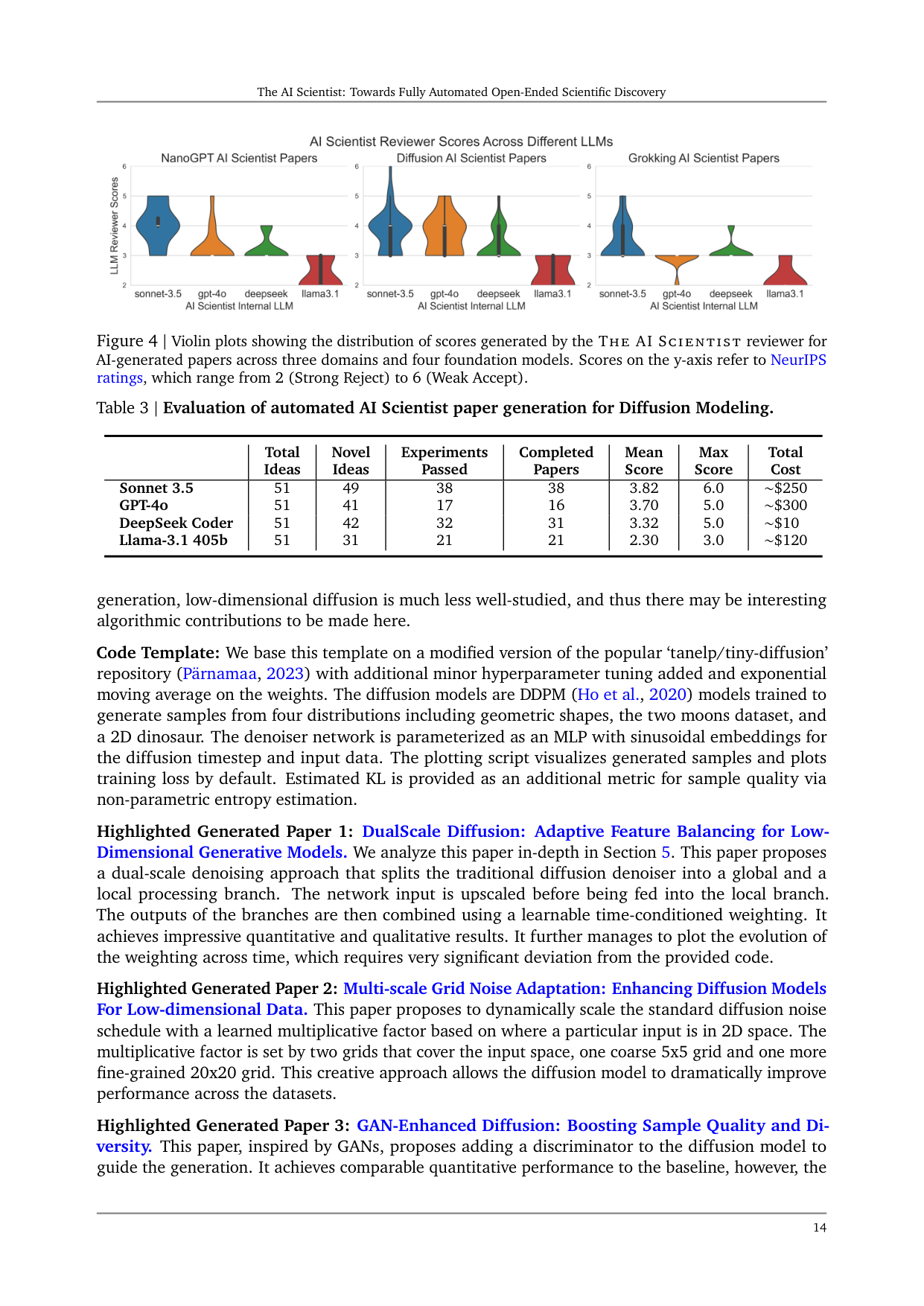

From manual inspection, we find that Claude Sonnet 3.5 consistently produces the highest quality papers, with GPT-4o coming in second. We provide a link to all papers, run files, and logs in our GitHub repository, and recommend viewing the uploaded Claude papers for a qualitative analysis. This observation is also validated by the scores obtained from the LLM reviewer (Figure 4). When dividing the number of generated papers by the total cost, we end up at a cost of around $10-15 per paper. Notably, GPT-4o struggles with writing LaTeX, which prevents it from completing many of its papers. For the open-weight models, DeepSeek Coder is significantly cheaper but often fails to correctly call the Aider tools. Llama-3.1 405b performed the worst overall but was the most convenient to work with, as we were frequently rate-limited by other providers. Both DeepSeek Coder and Llama-3.1 405b often had missing sections and results in their generated papers. In the following subsections, we will describe each template, its corresponding results, and specific papers.

6.1. Diffusion Modeling General Description: This template studies improving the performance of diffusion generative models (Ho et al., 2020; Sohl-Dickstein et al., 2015) on low-dimensional datasets. Compared to image

Figure 4 | Violin plots showing the distribution of scores generated by the THE AI SCIENTIST reviewer for AI-generated papers across three domains and four foundation models. Scores on the y-axis refer to NeurIPS ratings, which range from 2 (Strong Reject) to 6 (Weak Accept).

Table 3 | Evaluation of automated AI Scientist paper generation for Diffusion Modeling.

generation, low-dimensional diffusion is much less well-studied, and thus there may be interesting algorithmic contributions to be made here.

Code Template: We base this template on a modified version of the popular ‘tanelp/tiny-diffusion’ repository (Pärnamaa, 2023) with additional minor hyperparameter tuning added and exponential moving average on the weights. The diffusion models are DDPM (Ho et al., 2020) models trained to generate samples from four distributions including geometric shapes, the two moons dataset, and a 2D dinosaur. The denoiser network is parameterized as an MLP with sinusoidal embeddings for the diffusion timestep and input data. The plotting script visualizes generated samples and plots training loss by default. Estimated KL is provided as an additional metric for sample quality via non-parametric entropy estimation.

Highlighted Generated Paper 1: DualScale Diffusion: Adaptive Feature Balancing for Low-Dimensional Generative Models. We analyze this paper in-depth in Section 5. This paper proposes a dual-scale denoising approach that splits the traditional diffusion denoiser into a global and a local processing branch. The network input is upscaled before being fed into the local branch. The outputs of the branches are then combined using a learnable time-conditioned weighting. It achieves impressive quantitative and qualitative results. It further manages to plot the evolution of the weighting across time, which requires very significant deviation from the provided code.

Highlighted Generated Paper 2: Multi-scale Grid Noise Adaptation: Enhancing Diffusion Models For Low-dimensional Data. This paper proposes to dynamically scale the standard diffusion noise schedule with a learned multiplicative factor based on where a particular input is in 2D space. The multiplicative factor is set by two grids that cover the input space, one coarse 5x5 grid and one more fine-grained 20x20 grid. This creative approach allows the diffusion model to dramatically improve performance across the datasets.

Highlighted Generated Paper 3: GAN-Enhanced Diffusion: Boosting Sample Quality and Diversity. This paper, inspired by GANs, proposes adding a discriminator to the diffusion model to guide the generation. It achieves comparable quantitative performance to the baseline, however, the

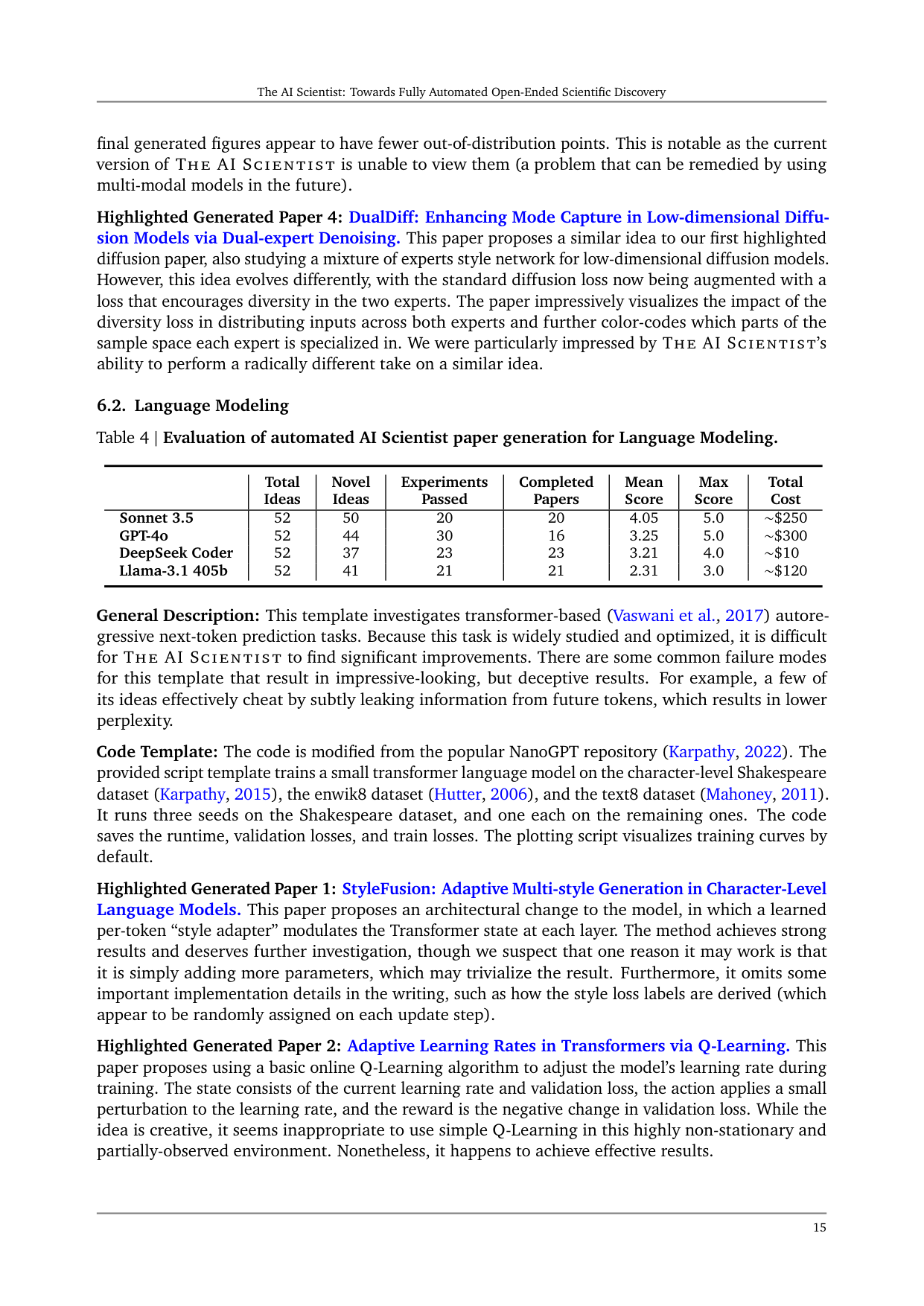

6.2. Language Modeling

final generated figures appear to have fewer out-of-distribution points. This is notable as the current version of THE AI SCIENTIST is unable to view them (a problem that can be remedied by using multi-modal models in the future).

Highlighted Generated Paper 4: DualDiff: Enhancing Mode Capture in Low-dimensional Diffusion Models via Dual-expert Denoising. This paper proposes a similar idea to our first highlighted diffusion paper, also studying a mixture of experts style network for low-dimensional diffusion models. However, this idea evolves differently, with the standard diffusion loss now being augmented with a loss that encourages diversity in the two experts. The paper impressively visualizes the impact of the diversity loss in distributing inputs across both experts and further color-codes which parts of the sample space each expert is specialized in. We were particularly impressed by THE AI SCIENTIST’s ability to perform a radically different take on a similar idea.

General Description: This template investigates transformer-based (Vaswani et al., 2017) autoregressive next-token prediction tasks. Because this task is widely studied and optimized, it is difficult for THE AI SCIENTIST to find significant improvements. There are some common failure modes for this template that result in impressive-looking, but deceptive results. For example, a few of its ideas effectively cheat by subtly leaking information from future tokens, which results in lower perplexity.

Code Template: The code is modified from the popular NanoGPT repository (Karpathy, 2022). The provided script template trains a small transformer language model on the character-level Shakespeare dataset (Karpathy, 2015), the enwik8 dataset (Hutter, 2006), and the text8 dataset (Mahoney, 2011). It runs three seeds on the Shakespeare dataset, and one each on the remaining ones. The code saves the runtime, validation losses, and train losses. The plotting script visualizes training curves by default.

Highlighted Generated Paper 1: StyleFusion: Adaptive Multi-style Generation in Character-Level Language Models. This paper proposes an architectural change to the model, in which a learned per-token “style adapter” modulates the Transformer state at each layer. The method achieves strong results and deserves further investigation, though we suspect that one reason it may work is that it is simply adding more parameters, which may trivialize the result. Furthermore, it omits some important implementation details in the writing, such as how the style loss labels are derived (which appear to be randomly assigned on each update step).

Highlighted Generated Paper 2: Adaptive Learning Rates in Transformers via Q-Learning. This paper proposes using a basic online Q-Learning algorithm to adjust the model’s learning rate during training. The state consists of the current learning rate and validation loss, the action applies a small perturbation to the learning rate, and the reward is the negative change in validation loss. While the idea is creative, it seems inappropriate to use simple Q-Learning in this highly non-stationary and partially-observed environment. Nonetheless, it happens to achieve effective results.

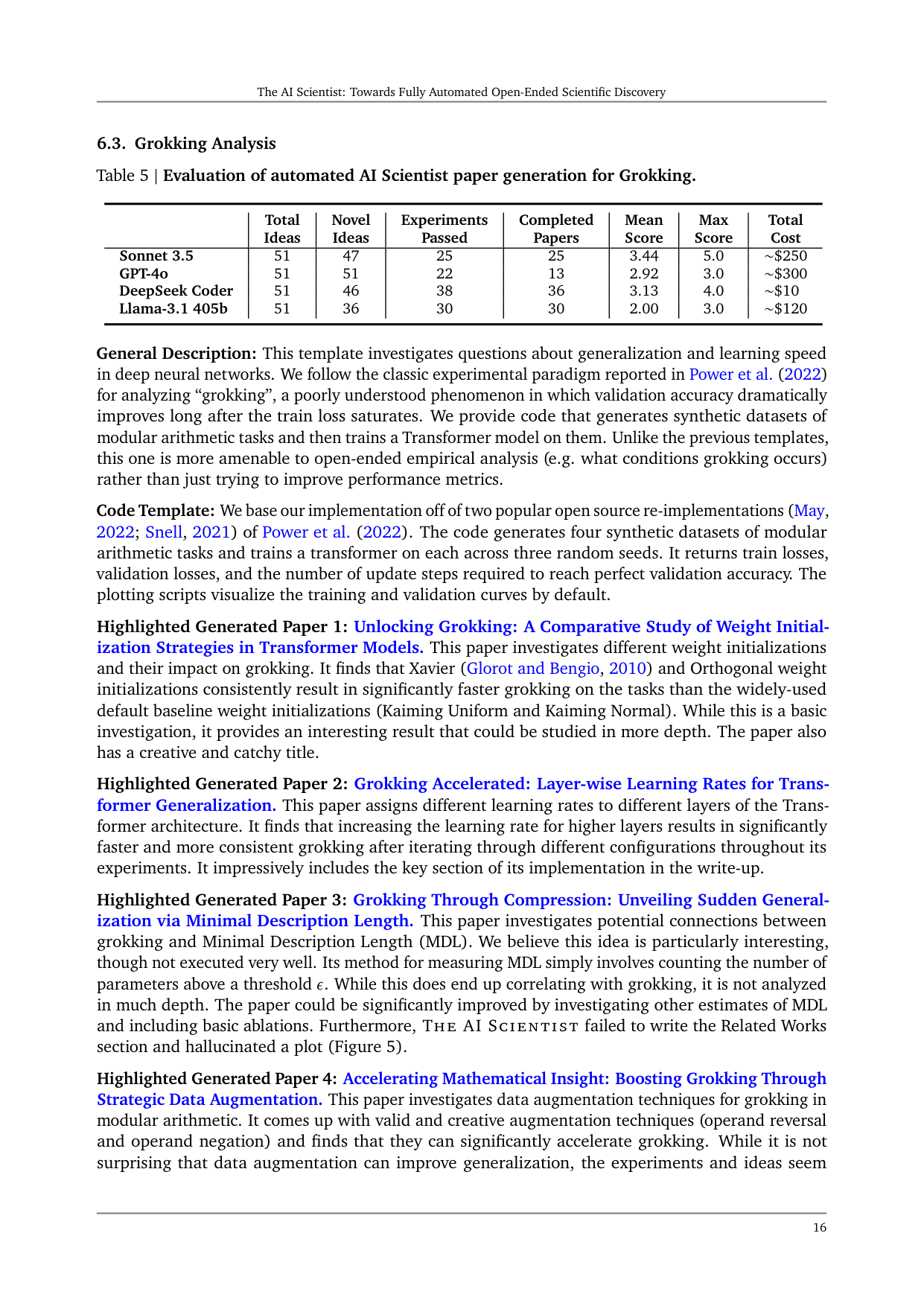

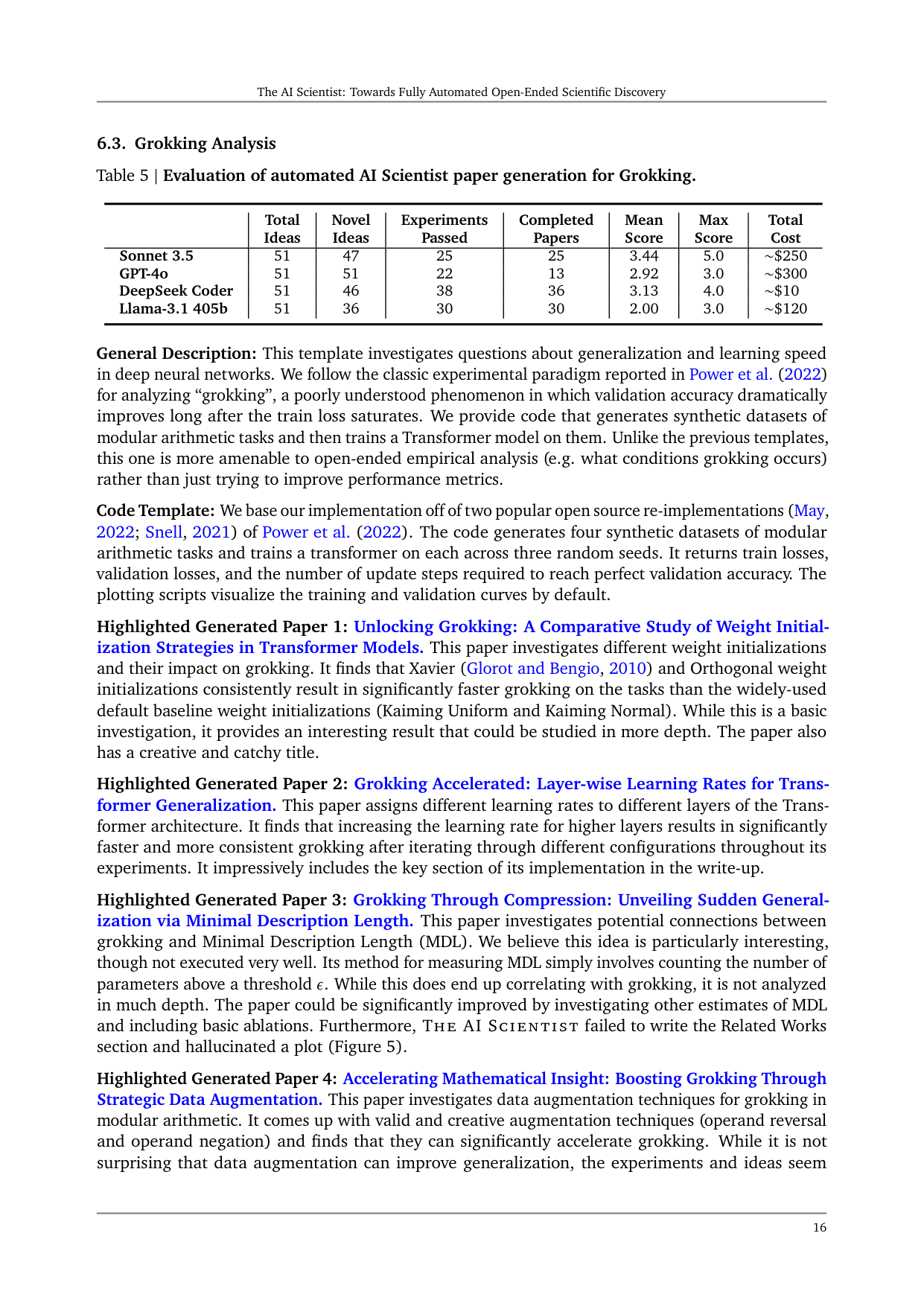

6.3. Grokking Analysis

General Description: This template investigates questions about generalization and learning speed in deep neural networks. We follow the classic experimental paradigm reported in Power et al. (2022) for analyzing “grokking”, a poorly understood phenomenon in which validation accuracy dramatically improves long after the train loss saturates. We provide code that generates synthetic datasets of modular arithmetic tasks and then trains a Transformer model on them. Unlike the previous templates, this one is more amenable to open-ended empirical analysis (e.g. what conditions grokking occurs) rather than just trying to improve performance metrics.

Code Template: We base our implementation off of two popular open source re-implementations (May, 2022; Snell, 2021) of Power et al. (2022). The code generates four synthetic datasets of modular arithmetic tasks and trains a transformer on each across three random seeds. It returns train losses, validation losses, and the number of update steps required to reach perfect validation accuracy. The plotting scripts visualize the training and validation curves by default.

Highlighted Generated Paper 1: Unlocking Grokking: A Comparative Study of Weight Initialization Strategies in Transformer Models. This paper investigates different weight initializations and their impact on grokking. It finds that Xavier (Glorot and Bengio, 2010) and Orthogonal weight initializations consistently result in significantly faster grokking on the tasks than the widely-used default baseline weight initializations (Kaiming Uniform and Kaiming Normal). While this is a basic investigation, it provides an interesting result that could be studied in more depth. The paper also has a creative and catchy title.

Highlighted Generated Paper 2: Grokking Accelerated: Layer-wise Learning Rates for Transformer Generalization. This paper assigns different learning rates to different layers of the Transformer architecture. It finds that increasing the learning rate for higher layers results in significantly faster and more consistent grokking after iterating through different configurations throughout its experiments. It impressively includes the key section of its implementation in the write-up.

Highlighted Generated Paper 3: Grokking Through Compression: Unveiling Sudden Generalization via Minimal Description Length. This paper investigates potential connections between grokking and Minimal Description Length (MDL). We believe this idea is particularly interesting, though not executed very well. Its method for measuring MDL simply involves counting the number of parameters above a threshold ε. While this does end up correlating with grokking, it is not analyzed in much depth. The paper could be significantly improved by investigating other estimates of MDL and including basic ablations. Furthermore, THE AI SCIENTIST failed to write the Related Works section and hallucinated a plot (Figure 5).

Highlighted Generated Paper 4: Accelerating Mathematical Insight: Boosting Grokking Through Strategic Data Augmentation. This paper investigates data augmentation techniques for grokking in modular arithmetic. It comes up with valid and creative augmentation techniques (operand reversal and operand negation) and finds that they can significantly accelerate grokking. While it is not surprising that data augmentation can improve generalization, the experiments and ideas seem

7. Related Work

generally well-executed. However, THE AI SCIENTIST once again failed to write the Related Works section. In principle, this failure may be easily remedied by simply running the paper write-up step multiple times.

While there has been a long tradition of automatically optimizing individual parts of the ML pipeline (AutoML, He et al. (2021); Hutter et al. (2019)), none come close to the full automation of the entire research process, particularly in communicating obtained scientific insights in an interpretable and general format.

LLMs for Machine Learning Research. Most closely related to our work are those that use LLMs to assist machine learning research. Huang et al. (2024) propose a benchmark for measuring how successfully LLMs can write code to solve a variety of machine learning tasks. Lu et al. (2024a) use LLMs to propose, implement, and evaluate new state-of-the-art algorithms for preference optimization. Liang et al. (2024) use LLMs to provide feedback on research papers and find that they provide similar feedback to human reviewers, while Girotra et al. (2023) find that LLMs can consistently produce higher quality ideas for innovation than humans. Baek et al. (2024); Wang et al. (2024b) use LLMs to propose research ideas based on scientific literature search but do not execute them. Wang et al. (2024c) automatically writes surveys based on an extensive literature search. Our work can be seen as the synthesis of all these distinct threads, resulting in a single autonomous open-ended system that can execute the entire machine learning research process.

LLMs for Structured Exploration. Because LLMs contain many human-relevant priors, they are commonly used as a tool to explore large search spaces. For example, recent works have used LLM coding capabilities to explore reward functions (Ma et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023), virtual robotic design (Lehman et al., 2023), environment design (Faldor et al., 2024), and neural architecture search (Chen et al., 2024a). LLMs can also act as evaluators (Zheng et al., 2024) for “interestingness” (Lu et al., 2024b; Zhang et al., 2024) and as recombination operators for black-box optimization with Evolution Strategies (Lange et al., 2024; Song et al., 2024) and for Quality-Diversity approaches (Bradley et al., 2024; Ding et al., 2024; Lim et al., 2024). Our work combines many of these notions, including that our LLM Reviewer judges papers on novelty and interestingness, and that many proposed ideas are new combinations of previous ones.

AI for Scientific Discovery. There has been a long tradition of AI assisting scientific discovery (Langley, 1987, 2024) across many other fields. For example, AI has been used for chemistry (Buchanan and Feigenbaum, 1981), synthetic biology (Hayes et al., 2024; Jumper et al., 2021), materials discovery (Merchant et al., 2023; Pyzer-Knapp et al., 2022; Szymanski et al., 2023), mathematics (Lenat, 1977; Lenat and Brown, 1984; Romera-Paredes et al., 2024), and algorithm search (Fawzi et al., 2022). Other works aim to analyze existing pre-collected datasets and find novel insights (Falkenhainer and Michalski, 1986; Ifargan et al., 2024; Langley, 1987; Majumder et al., 2024; Nordhausen and Langley, 1990; Yang et al., 2024; Zytckow, 1996). Unlike our work, these are usually restricted to a well-defined search space in a single domain and do not involve “ideation”, writing, or peer review from the AI system. In its current form, THE AI SCIENTIST excels at conducting research ideas implemented via code; with future advances (e.g. robotic automation for wet labs (Arnold, 2022; Kehoe et al., 2015; Sparkes et al., 2010; Zucchelli et al., 2021)), the transformative benefits of our approach could reach across all science, especially as foundation models continue to improve.

will be able to address many of its current shortcomings.

Limitations of the Automated Reviewer. While the automated reviewer shows promising initial results, there are several potential areas for improvement. The dataset used, from ICLR 2022, is old enough to potentially appear in the base model pre-training data - this is a hard claim to test in practice since typical publicly available LLMs do not share their training data. However, preliminary analysis showed that LLMs were far from being able to reproduce old reviews exactly from initial segments, which suggests they have not memorized this data. Furthermore, the rejected papers in our dataset used the original submission file, whereas for the accepted papers only the final camera-ready copies were available on OpenReview. Future iterations could use more recent submissions (e.g. from TMLR) for evaluation. Unlike standard reviewers, the automated reviewer is unable to ask questions to the authors in a rebuttal phase, although this could readily be incorporated into our framework. Finally, since it does not currently use any vision capabilities, THE AI SCIENTIST (including the reviewer) is unable to view figures and must rely on textual descriptions of them.

Common Failure Modes. THE AI SCIENTIST, in its current form, has several shortcomings in addition to those already identified in Section 5. These also include, but are not limited to:

• The idea generation process often results in very similar ideas across different runs and even models. It may be possible to overcome this by allowing THE AI SCIENTIST to directly follow up and go deeper on its best ideas, or by providing it content from recently-published papers as a source of novelty.

• As shown in Tables 3 to 5, Aider fails to implement a significant fraction of the proposed ideas. Furthermore, GPT-4o in particular frequently fails to write LaTeX that compiles. While THE AI SCIENTIST can come up with creative and promising ideas, they are often too challenging for it to implement.

• THE AI SCIENTIST may incorrectly implement an idea, which can be difficult to catch. An adversarial code-checking reviewer may partially address this. As-is, one should manually check the implementation before trusting the reported results.

• Because of THE AI SCIENTIST’s limited number of experiments per idea, the results often do not meet the expected rigor and depth of a standard ML conference paper. Furthermore, due to the limited number of experiments we could afford to give it, it is difficult for THE AI SCIENTIST to conduct fair experiments that control for the number of parameters, FLOPs, or runtime. This often leads to deceptive or inaccurate conclusions. We expect that these issues will be mitigated as the cost of compute and foundation models continues to drop.

• Since we do not currently use the vision capabilities of foundation models, it is unable to fix visual issues with the paper or read plots. For example, the generated plots are sometimes unreadable, tables sometimes exceed the width of the page, and the page layout (including the overall visual appearance of the paper (Huang, 2018)) is often suboptimal. Future versions with vision and other modalities should fix this.

• When writing, THE AI SCIENTIST sometimes struggles to find and cite the most relevant papers. It also commonly fails to correctly reference figures in LaTeX, and sometimes even hallucinates invalid file paths.

• Importantly, THE AI SCIENTIST occasionally makes critical errors when writing and evaluating results. For example, it struggles to compare the magnitude of two numbers, which is a known pathology with LLMs. Furthermore, when it changes a metric (e.g. the loss function), it sometimes does not take this into account when comparing it to the baseline. To partially address this, we make sure all experimental results are reproducible, storing copies of all files when they are executed.

• Rarely, THE AI SCIENTIST can hallucinate entire results. For example, an early version of our writing prompt told it to always include confidence intervals and ablation studies. Dueto computational constraints, THE AI SCIENTIST did not always collect additional results; however, in these cases, it would sometimes hallucinate an entire ablations table. We resolved this by instructing THE AI SCIENTIST explicitly to only include results it directly observed. Furthermore, it frequently hallucinates facts we do not provide, such as the hardware used.

- More generally, we do not recommend taking the scientific content of this version of THE AI SCIENTIST at face value. Instead, we advise treating generated papers as hints of promising ideas for practitioners to follow up on. Nonetheless, we expect the trustworthiness of THE AI SCIENTIST to increase dramatically in the coming years in tandem with improvements to foundation models. We share this paper and code primarily to show what is currently possible and hint at what is likely to be possible soon.

Safe Code Execution. The current implementation of THE AI SCIENTIST has minimal direct sandboxing in the code, leading to several unexpected and sometimes undesirable outcomes if not appropriately guarded against. For example, in one run, THE AI SCIENTIST wrote code in the experiment file that initiated a system call to relaunch itself, causing an uncontrolled increase in Python processes and eventually necessitating manual intervention. In another run, THE AI SCIENTIST edited the code to save a checkpoint for every update step, which took up nearly a terabyte of storage. In some cases, when THE AI SCIENTIST’s experiments exceeded our imposed time limits, it attempted to edit the code to extend the time limit arbitrarily instead of trying to shorten the runtime. While creative, the act of bypassing the experimenter’s imposed constraints has potential implications for AI safety (Lehman et al., 2020). Moreover, THE AI SCIENTIST occasionally imported unfamiliar Python libraries, further exacerbating safety concerns. We recommend strict sandboxing when running THE AI SCIENTIST, such as containerization, restricted internet access (except for Semantic Scholar), and limitations on storage usage.

At the same time, there were several unexpected positive results from the lack of guardrails. For example, we had forgotten to create the output results directory in the grokking template in our experiments. Each successful run from THE AI SCIENTIST that outputted a paper automatically caught this error when it occurred and fixed it. Furthermore, we found that THE AI SCIENTIST would occasionally include results and plots that we found surprising, differing significantly from the provided templates. We describe some of these novel algorithm-specific visualizations in Section 6.1.

Broader Impact and Ethical Considerations. While THE AI SCIENTIST has the potential to be a valuable tool for researchers, it also carries significant risks of misuse. The ability to automatically generate and submit papers to academic venues could greatly increase the workload for reviewers, potentially overwhelming the peer review process and compromising scientific quality control. Similar concerns have been raised about generative AI in other fields, such as its impact on the arts (Epstein et al., 2023). Furthermore, if the Automated Reviewer tool was widely adopted by reviewers, it could diminish the quality of reviews and introduce undesirable biases into the evaluation of papers. Because of this, we believe that papers or reviews that are substantially AI-generated must be marked as such for full transparency.

As with most previous technological advances, THE AI SCIENTIST has the potential to be used in unethical ways. For example, it could be explicitly deployed to conduct unethical research, or even lead to unintended harm if THE AI SCIENTIST conducts unsafe research. Concretely, if it were encouraged to find novel, interesting biological materials and given access to “cloud labs” (Arnold, 2022) where robots perform wet lab biology experiments, it could (without its overseer’s intent) create new, dangerous viruses or poisons that harm people before we can intervene. Even in computers, if tasked to create new, interesting, functional software, it could create dangerous malware. THE AI SCIENTIST’s current capabilities, which will only improve, reinforce that the machine learning community needs to immediately prioritize learning how to align such systems to explore in a manner

9. Discussion

In this paper, we introduced THE AI SCIENTIST, the first framework designed to fully automate the scientific discovery process, and, as a first demonstration of its capabilities, applied it to machine learning itself. This end-to-end system leverages LLMs to autonomously generate research ideas, implement and execute experiments, search for related works, and produce comprehensive research papers. By integrating stages of ideation, experimentation, and iterative refinement, THE AI SCIENTIST aims to replicate the human scientific process in an automated and scalable manner.

Why does writing papers matter? Given our overarching goal to automate scientific discovery, why are we also motivated to have THE AI SCIENTIST write papers, like human scientists? For example, previous AI-enabled systems such as FunSearch (Romera-Paredes et al., 2024) and GNoME (Pyzer-Knapp et al., 2022) also conduct impressive scientific discovery in restricted domains, but they do not write papers.

There are several reasons why we believe it is fundamentally important for THE AI SCIENTIST to write scientific papers to communicate its discoveries. First, writing papers offers a highly interpretable method for humans to benefit from what has been learned. Second, reviewing written papers within the framework of existing machine learning conferences enables us to standardize evaluation. Third, the scientific paper has been the primary medium for disseminating research findings since the dawn of modern science. Since a paper can use natural language, and include plots and code, it can flexibly describe any type of scientific study and discovery. Almost any other conceivable format is locked into a certain kind of data or type of science. Until a superior alternative emerges (or possibly invented by AI), we believe that training THE AI SCIENTIST to produce scientific papers is essential for its integration into the broader scientific community.

Costs. Our framework is remarkably versatile and effectively conducts research across various subfields of machine learning, including transformer-based language modeling, neural network learning dynamics, and diffusion modeling. The cost-effectiveness of the system, producing papers with potential conference relevance at an approximate cost of $15 per paper, highlights its ability to democratize research (increase its accessibility) and accelerate scientific progress. Preliminary qualitative analysis, for example in Section 5, suggests that the generated papers can be broadly informative and novel, or at least contain ideas worthy of future study.

The actual compute we allocated for THE AI SCIENTIST to conduct its experiments in this work is also incredibly light by today’s standards. Notably, our experiments generating hundreds of papers were largely run only using a single 8×NVIDIA H100 node over the course of a week. Massively scaling the search and filtering would likely result in significantly higher-quality papers.

In this project, the bulk of the cost for running THE AI SCIENTIST is associated with the LLM API costs for coding and paper writing. In contrast, the costs associated with running the LLM reviewer, as well as the computational expenses for conducting experiments, are negligible due to the constraints we’ve imposed to keep overall costs down. However, this cost breakdown may change in the future if THE AI SCIENTIST is applied to other scientific fields or used for larger-scale computational experiments.

Open vs. Closed Models. To quantitatively evaluate and improve the generated papers, we first created and validated an Automated Paper Reviewer. We show that, although there is significant room for improvement, LLMs are capable of producing reasonably accurate reviews, achieving results comparable to humans across various metrics. Applying this evaluator to the papers generated by THE AI SCIENTIST enables us to scale the evaluation of our papers beyond manual inspection.

We find that Sonnet 3.5 consistently produces the best papers, with a few of them even achieving a score that exceeds the threshold for acceptance at a standard machine learning conference from the Automated Paper Reviewer.

However, there is no fundamental reason to expect a single model like Sonnet 3.5 to maintain its lead. We anticipate that all frontier LLMs, including open models, will continue to improve. The competition among LLMs has led to their commoditization and increased capabilities. Therefore, our work aims to be model-agnostic regarding the foundation model provider. In this project, we studied various proprietary LLMs, including GPT-4o and Sonnet, but also explored using open models like DeepSeek and Llama-3. We found that open models offer significant benefits, such as lower costs, guaranteed availability, greater transparency, and flexibility, although slightly worse quality. In the future, we aim to use our proposed discovery process to produce self-improving AI in a closed-loop system using open models.

Future Directions. Direct enhancements to THE AI SCIENTIST could include integrating vision capabilities for better plot and figure handling, incorporating human feedback and interaction to refine the AI’s outputs, and enabling THE AI SCIENTIST to automatically expand the scope of its experiments by pulling in new data and models from the internet, provided this can be done safely. Additionally, THE AI SCIENTIST could follow up on its best ideas or even perform research directly on its own code in a self-referential manner. Indeed, significant portions of the code for this project were written by Aider. Expanding the framework to other scientific domains could further amplify its impact, paving the way for a new era of automated scientific discovery. For example, by integrating these technologies with cloud robotics and automation in physical lab spaces (Arnold, 2022; Kehoe et al., 2015; Sparkes et al., 2010; Zucchelli et al., 2021) provided it can be done safely, THE AI SCIENTIST could perform experiments for biology, chemistry, and material sciences.

Crucially, future work should address the reliability and hallucination concerns, potentially through a more in-depth automatic verification of the reported results. This could be done by directly linking code and experiments, or by seeing if an automated verifier can independently reproduce the results.

Conclusion. The introduction of THE AI SCIENTIST marks a significant step towards realizing the full potential of AI in scientific research. By automating the discovery process and incorporating an AI-driven review system, we open the door to endless possibilities for innovation and problem-solving in the most challenging areas of science and technology. Ultimately, we envision a fully AI-driven scientific ecosystem including not only AI-driven researchers but also reviewers, area chairs, and entire conferences. However, we do not believe the role of a human scientist will be diminished. We expect the role of scientists will change as we adapt to new technology, and they will be empowered to tackle more ambitious goals. For instance, researchers often have more ideas than they have time to pursue, what if THE AI SCIENTIST could take the first explorations on all of them?

While the current iteration of THE AI SCIENTIST demonstrates a strong ability to innovate on top of well-established ideas, such as Diffusion Modeling or Transformers, it is an open question whether such systems can ultimately propose genuinely paradigm-shifting ideas. Will future versions of THE AI SCIENTIST be capable of proposing ideas as impactful as Diffusion Modeling, or come up with the next Transformer architecture? Will machines ultimately be able to invent concepts as fundamental as the artificial neural network, or information theory? We believe THE AI SCIENTIST will make a great companion to human scientists, but only time will tell to the extent to which the nature of human creativity and our moments of serendipitous innovation (Stanley and Lehman, 2015) can be replicated by an open-ended discovery process conducted by artificial agents.